10: Georgia’s Oldest Mammals

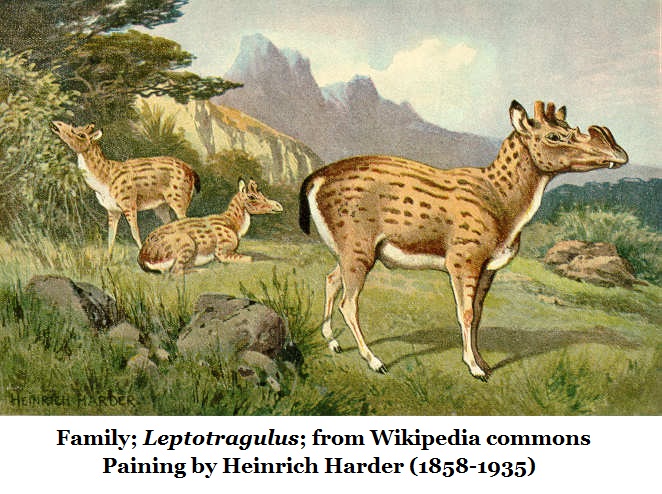

The deer-like Leptotragulus medius

& a Mesonychid predator

Smithsonian

National Museum of Natural History

Leptotragulus medius

The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History holds fossils, discovered in Georgia, from the hoofed, deer-like herbivore named Leptotragulus medius that are at least 42 million years old; the animal was only very distantly related to modern deer. The fossils held by the Smithsonian include skull fragments, a partial left mandible (jaw) and two premolar teeth (Catalog #PAL 244447).

Sadly, no images of the specimens are available.

According to their records the fossils were collected in Jefferson County by Samuel W. McCallie.

McCallie, a researcher with a fascinating history, stood as Georgia State Geologist from 1908 to 1933 and was actively producing research for the Georgia Geological Survey as early as 1896. He was State Geologist during the famous and exhaustive 1911 Coastal Plain Survey by Veatch & Stephenson, he even contributed many field observations to that report.

No information is given in the online catalog over the precise location in Jefferson County. No date of collection nor when the Smithsonian received the fossils is reported by the museum.

The fossils were likely collected sometime after 1911 as no mention of them occurs in the 1911 Coastal Plain Survey. We’ll look at the Jefferson County problem in a minute.

To the author’s knowledge this find has never been published anywhere beyond the Smithsonian’s on-line catalog.

At the time this article was written the find did not occur in the Paleobiology Database which is a global record and was built on peer-reviewed, published specimens.

The Paleobiology Database records only 6 reports of this species, with all originating in Utah and Wyoming. A total of 65 specimens of the species were collected. Many of these are apparently in the Smithsonian. A search restricted to the genus gives 14 reports with 13 still being restricted to Utah & Wyoming, the 14th coming from western Canada. The species is unreported in Eastern North America.

The Smithsonian record calls this find a camelid; it’s not. That’s a relic from the original record. Leptotragulus medius was a hoofed herbivore, similar to a modern white-tailed deer but only very distantly related, much older and much smaller. A dog sized animal. Some sources say about 30 pounds for an adult.

Specifically it was of the Order; Artiodactyla, an even-toed ungulate. Georgia’s white tailed deer share this order, as do camels. Both are only distantly related to our Leptotragulus medius.

Ungulates are a highly diverse clade of hoofed mammals; even-toed ungulates walk on two hooves per leg and include goats, deer, cattle, giraffes, hippos… and many others. Whales emerged from the order Artiodcatyla; their distant terrestrial ancestors were even-toed ungulates.

Odd-toed ungulates are of the Order Perissodactyls; including the horses, donkeys, zebras, rhinos and tapirs. They walk on a single hoof, a single toe per leg.

The modern diversity of ungulates is diminished when compared to their fossil record; hoofed predators once walked North America; even Georgia. Chilling thought isn’t it?

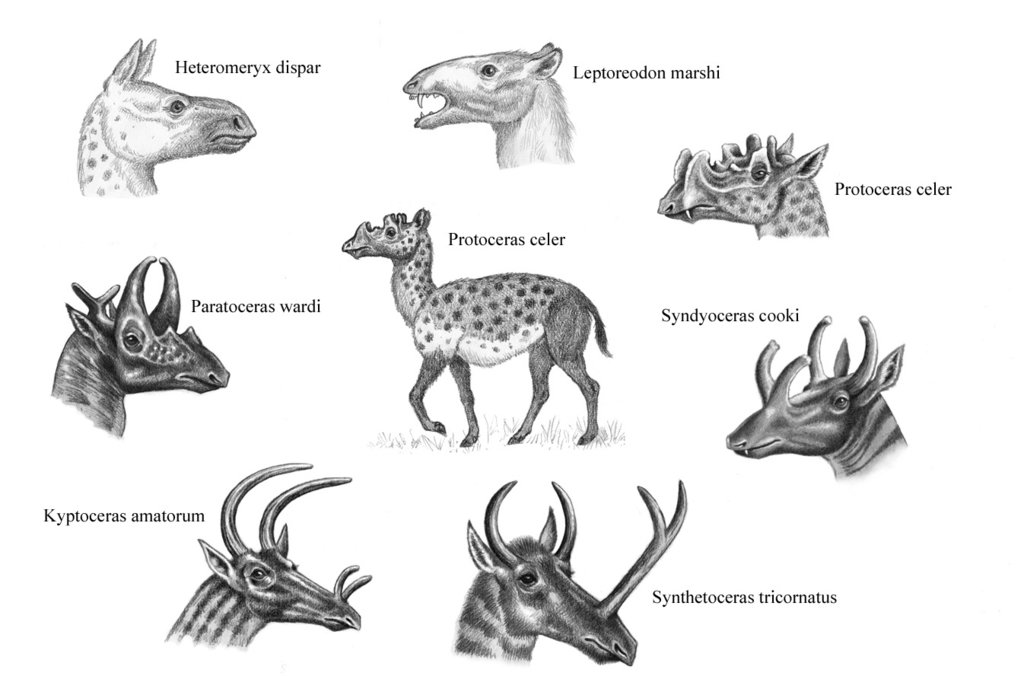

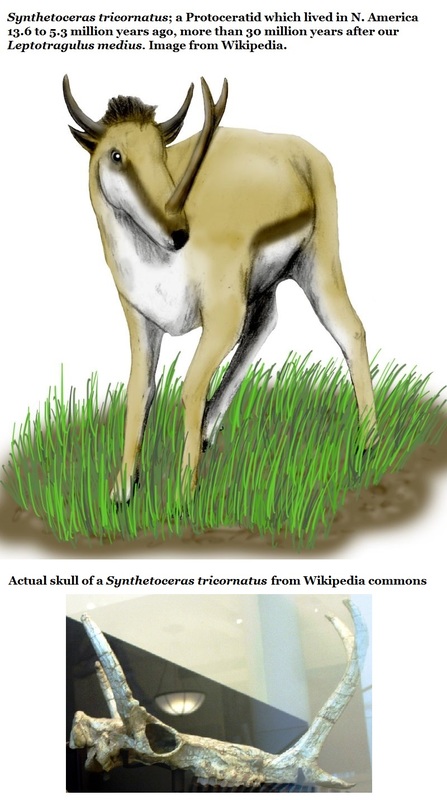

Our Leptotragulus medius was of the family; Protoceratidae (erected by Marsh I 1891) which is now extinct. The species was described in 1919. What separates the protoceratids from other ungulates is the horns or antlers of the males. Along with the typical antlers near the ears there were also antlers on the snout. Some species had a single snout antler. Some had a pair of snout antlers. In some species these were large enough to be used in mating combat. Females either lacked horns or they were greatly diminished. It’s believed that these were probably herding animals.

The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History holds fossils, discovered in Georgia, from the hoofed, deer-like herbivore named Leptotragulus medius that are at least 42 million years old; the animal was only very distantly related to modern deer. The fossils held by the Smithsonian include skull fragments, a partial left mandible (jaw) and two premolar teeth (Catalog #PAL 244447).

Sadly, no images of the specimens are available.

According to their records the fossils were collected in Jefferson County by Samuel W. McCallie.

McCallie, a researcher with a fascinating history, stood as Georgia State Geologist from 1908 to 1933 and was actively producing research for the Georgia Geological Survey as early as 1896. He was State Geologist during the famous and exhaustive 1911 Coastal Plain Survey by Veatch & Stephenson, he even contributed many field observations to that report.

No information is given in the online catalog over the precise location in Jefferson County. No date of collection nor when the Smithsonian received the fossils is reported by the museum.

The fossils were likely collected sometime after 1911 as no mention of them occurs in the 1911 Coastal Plain Survey. We’ll look at the Jefferson County problem in a minute.

To the author’s knowledge this find has never been published anywhere beyond the Smithsonian’s on-line catalog.

At the time this article was written the find did not occur in the Paleobiology Database which is a global record and was built on peer-reviewed, published specimens.

The Paleobiology Database records only 6 reports of this species, with all originating in Utah and Wyoming. A total of 65 specimens of the species were collected. Many of these are apparently in the Smithsonian. A search restricted to the genus gives 14 reports with 13 still being restricted to Utah & Wyoming, the 14th coming from western Canada. The species is unreported in Eastern North America.

The Smithsonian record calls this find a camelid; it’s not. That’s a relic from the original record. Leptotragulus medius was a hoofed herbivore, similar to a modern white-tailed deer but only very distantly related, much older and much smaller. A dog sized animal. Some sources say about 30 pounds for an adult.

Specifically it was of the Order; Artiodactyla, an even-toed ungulate. Georgia’s white tailed deer share this order, as do camels. Both are only distantly related to our Leptotragulus medius.

Ungulates are a highly diverse clade of hoofed mammals; even-toed ungulates walk on two hooves per leg and include goats, deer, cattle, giraffes, hippos… and many others. Whales emerged from the order Artiodcatyla; their distant terrestrial ancestors were even-toed ungulates.

Odd-toed ungulates are of the Order Perissodactyls; including the horses, donkeys, zebras, rhinos and tapirs. They walk on a single hoof, a single toe per leg.

The modern diversity of ungulates is diminished when compared to their fossil record; hoofed predators once walked North America; even Georgia. Chilling thought isn’t it?

Our Leptotragulus medius was of the family; Protoceratidae (erected by Marsh I 1891) which is now extinct. The species was described in 1919. What separates the protoceratids from other ungulates is the horns or antlers of the males. Along with the typical antlers near the ears there were also antlers on the snout. Some species had a single snout antler. Some had a pair of snout antlers. In some species these were large enough to be used in mating combat. Females either lacked horns or they were greatly diminished. It’s believed that these were probably herding animals.

Scientific Importance

This is a very interesting fossil needing further research.

If this Georgia specimen in the Smithsonian were confirmed and published as Leptotragulus medius in a peer-reviewed research paper; that would represent the only known occurrence of this species East of Wyoming and suggest continent-wide distribution.

The Smithsonian places Leptotragulus medius in the Uintan Stage of the North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA). Uhen’s Paleobiology Database agrees with this. This dates the fossil from between 46.2 to 42 million years of age. That’s the Lutetian Stage of the Middle Eocene Epoch. If confirmed this would make it the second oldest known Georgia mammal. (We’ll look at the oldest in a moment.) It would also be the only land mammal, from this time-frame, confirmed in Georgia; perhaps the Southeast.

We have no information about the sediments which produced the specimen, so stratigraphy cannot confirm the age of the fossil. So the age of the specimen can only be derived by identification of the species. If the fossils are in good condition, this shouldn’t represent a problem. There seems to be a good supply of western fossils to compare to the Georgia specimens for confirmation.

Paul F. Huddlestun is Georgia’s foremost expert on Coastal Plain sediments as a whole; as a biostratigraphist he spent his career researching Coastal Plain stratigraphy, across the Southeast, for the now defunct Georgia Geologic Survey.

Though retired now to New Mexico he visits family in Georgia frequently and has come to Warner Robins a couple times to spend the day in the field with me. I’m honored by his attention.

Huddlestun authored, or co-authored, the Georgia Environmental Protect Division’s reports on the Late Eocene through Pleistocene sediments and assembled the current Correlation Chart Georgia Coastal Plain (1981), which he is currently updating for this website. This correlation chart covers sediments from the recent ice ages and reaches back deep into the Cretaceous Period.

When asked in an email about this find he replied as below, but the sediments he mentions are admittedly too young to match the age of the species. As he explains; this could mean that the species is incorrectly identified, there are older sediments which aren’t recognized or that the specimen was found sub-surface. Any of which are possible since we have so little info on the location.

This is a very interesting fossil needing further research.

If this Georgia specimen in the Smithsonian were confirmed and published as Leptotragulus medius in a peer-reviewed research paper; that would represent the only known occurrence of this species East of Wyoming and suggest continent-wide distribution.

The Smithsonian places Leptotragulus medius in the Uintan Stage of the North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA). Uhen’s Paleobiology Database agrees with this. This dates the fossil from between 46.2 to 42 million years of age. That’s the Lutetian Stage of the Middle Eocene Epoch. If confirmed this would make it the second oldest known Georgia mammal. (We’ll look at the oldest in a moment.) It would also be the only land mammal, from this time-frame, confirmed in Georgia; perhaps the Southeast.

We have no information about the sediments which produced the specimen, so stratigraphy cannot confirm the age of the fossil. So the age of the specimen can only be derived by identification of the species. If the fossils are in good condition, this shouldn’t represent a problem. There seems to be a good supply of western fossils to compare to the Georgia specimens for confirmation.

Paul F. Huddlestun is Georgia’s foremost expert on Coastal Plain sediments as a whole; as a biostratigraphist he spent his career researching Coastal Plain stratigraphy, across the Southeast, for the now defunct Georgia Geologic Survey.

Though retired now to New Mexico he visits family in Georgia frequently and has come to Warner Robins a couple times to spend the day in the field with me. I’m honored by his attention.

Huddlestun authored, or co-authored, the Georgia Environmental Protect Division’s reports on the Late Eocene through Pleistocene sediments and assembled the current Correlation Chart Georgia Coastal Plain (1981), which he is currently updating for this website. This correlation chart covers sediments from the recent ice ages and reaches back deep into the Cretaceous Period.

When asked in an email about this find he replied as below, but the sediments he mentions are admittedly too young to match the age of the species. As he explains; this could mean that the species is incorrectly identified, there are older sediments which aren’t recognized or that the specimen was found sub-surface. Any of which are possible since we have so little info on the location.

05/June/2016

Thomas:

Jefferson County covers a lot of north-south territory.

If the bones come from northern Jefferson County, it would almost have to be from the lower Barnwell, i.e., the Irwinton Sand. Being an artiodactyl, I would expect it to have been found in a relatively nearshore deposit. That makes the Irwinton close enough.

If the fossil came from southern Jefferson County, the Tobacco Road is a possibility. All perimarine Middle Eocene deposits are too deeply buried in Jefferson County to be a likely contender.

No marine or nonmarine fossils have been reported from the farther updip, kaolinitic, Middle Eocene Huber Formation in the Wrens area. So, the problem is the location of the find and its elevation.

Without that, the most likely stratigraphic positions would be Lower Jacksonian, lower Barnwell, Dry Branch Formation, Irwinton Sand Member. I hope this helps a little.

Paul

If a professional Georgia paleontologist were to go to Washington and review the find for possible publication; wouldn’t it be interesting if Huddlestun were invited along? The retired biostratigraphist could have insights into the possible source formation of the fossils.

Thomas:

Jefferson County covers a lot of north-south territory.

If the bones come from northern Jefferson County, it would almost have to be from the lower Barnwell, i.e., the Irwinton Sand. Being an artiodactyl, I would expect it to have been found in a relatively nearshore deposit. That makes the Irwinton close enough.

If the fossil came from southern Jefferson County, the Tobacco Road is a possibility. All perimarine Middle Eocene deposits are too deeply buried in Jefferson County to be a likely contender.

No marine or nonmarine fossils have been reported from the farther updip, kaolinitic, Middle Eocene Huber Formation in the Wrens area. So, the problem is the location of the find and its elevation.

Without that, the most likely stratigraphic positions would be Lower Jacksonian, lower Barnwell, Dry Branch Formation, Irwinton Sand Member. I hope this helps a little.

Paul

If a professional Georgia paleontologist were to go to Washington and review the find for possible publication; wouldn’t it be interesting if Huddlestun were invited along? The retired biostratigraphist could have insights into the possible source formation of the fossils.

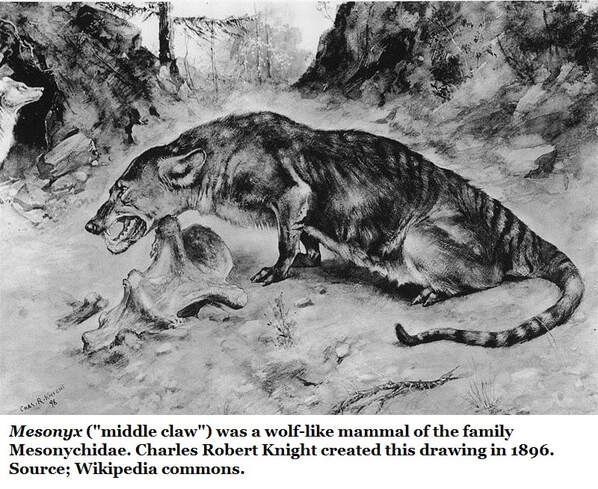

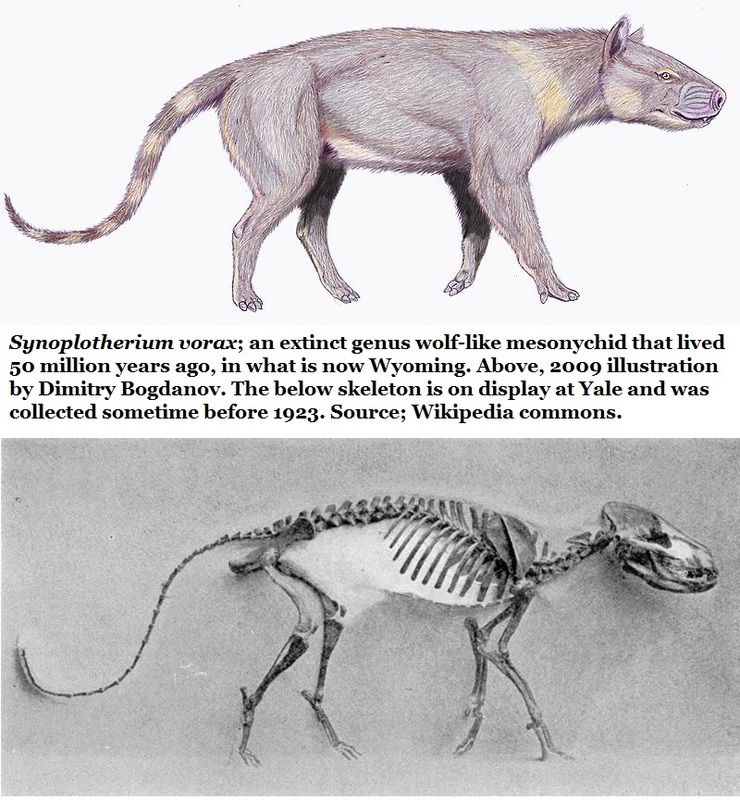

Georgia’s Mesonychid

Our oldest Mammal lived perhaps 50 million years ago.

Our oldest Mammal lived perhaps 50 million years ago.

The Smithsonian also holds a Mesonychid collected from Georgia. The specimen (Catalog# USNM V 25002) is the proximal (upper) end of a right femur.

The Smithsonian has published no images of the specimens.

The Smithsonian has published no images of the specimens.

The record shows that it was collected in 1967. No location within Georgia is given. The record lists the McBean Formation as the matrix.

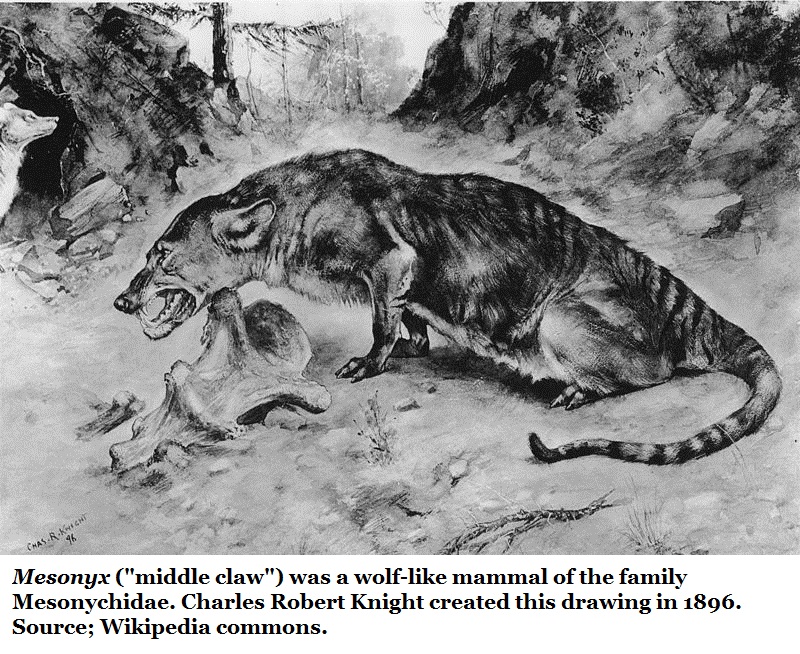

Mesonychids are essentially medium to large hoofed predators, of the Order Mesonychia and the Family Mesonychidae which was erected by Cope in 1875.

Mesonychids are essentially medium to large hoofed predators, of the Order Mesonychia and the Family Mesonychidae which was erected by Cope in 1875.

The earliest species walked flat on their toes, by the Late Eocene they likely walked on hooves. Called wolves-with-hooves they were effective predators, probably capable of taking large prey and were adapted to running. They emerged into the fossil record during the Early Paleocene about 64 million years ago, proliferated during the Early and Middle Eocene, declined in the Late Eocene and found extinction about 33 million years ago in the Early Oligocene.

The Smithsonian assigns an age of 55.4 to 50.3 million years old, by placing the fossil in the Wasatchian Stage of the North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA). This would place the fossil in the Ypresian Stage of the early Eocene. The author is unaware of any other fossils, of any type, in Georgia from the Ypresian, nor of any Ypresian age exposures.

If confirmed that would make this specimen Georgia’s oldest mammal.

There is no information offered about who collected the sample.

Returning to Uhen’s Paleobiology Database and searching the Family Mesonychidae, there are no reports east of Texas. There are 169 total scattered occurrences in SW Texas, NW New Mexico, many in Central & W Colorado, NE Utah, A heavy cluster in Central & N Wyoming, a few in Montana and North Dakota. West Mexico and Canada also report finds.

If this find were confirmed as listed in the Smithsonian catalog it would be the first Mesonychid reported in Eastern North America.

As ever, there are problems. The matrix is reported as the McBean formation which was isn’t well covered in Georgia’s literature. In 1911 Veatch & Stephenson considered this a Middle Eocene, Claiborne Stage formation.

The Claiborne Stage is a regional term and if applied to the International Stratigraphic Chart is would in include the early-mid Lutetain Stage and early Bartonian Stage. This roughly dates the McBean Formation to between 46 and 39 million years old.

That’s a far cry from the 55.4 to 50.3 mya (million years ago) that represents the Wasatchian Stage of NALMA. This is a problem which potential researchers would have to address.

The latest reference of the McBean Formation that the author is aware of comes from Richard Hulbert's paper introducing Georgiacetus vogtlensis as a genus & species.(A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale {Mammalia, Cetacea, Archaeoceti} and Associated Biota from Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry, and David P. Aleshire; Journal of Paleontology; September 1998)

In the Georgiacetus paper the following quote appears:

Lithology of the Blue Bluff unit.-All strata in the SRS/VEGP region biostratigraphically equivalent to the upper Lisbon Formation of the Gulf Coastal Plain were traditionally referred to the McBean Formation (e.g., Veatch and Stephenson, 1911; Cooke, 1943; Nystrom et al., 1991). Huddlestun and Hetrick (1986) greatly restricted the McBean geographically and considered it a member of the Lisbon Formation. They also recognized a second stratigraphic unit in the region, informally named the Blue Bluff unit, that was a lateral equivalent of their restricted McBean. Fallow and Price (1995) subdivided the traditional McBean into three formations, the Blue Bluff, Tinker, and Santee (Fig. 2). The Blue Bluff unit is present in the vicinity of the VEGP and produced the fossils described in this study.

...The most recent numeric estimates for the boundaries of NP16 are 43.4 to 40.4 Ma, and this zone is correlated with the late Lutetian and earliest Bartonian ages (Berggren et al., 1995).

There is also Sam Pickering’s 1970 Bulletin 81 of the Georgia Geologic Survey. (Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry & Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia)

The Smithsonian assigns an age of 55.4 to 50.3 million years old, by placing the fossil in the Wasatchian Stage of the North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA). This would place the fossil in the Ypresian Stage of the early Eocene. The author is unaware of any other fossils, of any type, in Georgia from the Ypresian, nor of any Ypresian age exposures.

If confirmed that would make this specimen Georgia’s oldest mammal.

There is no information offered about who collected the sample.

Returning to Uhen’s Paleobiology Database and searching the Family Mesonychidae, there are no reports east of Texas. There are 169 total scattered occurrences in SW Texas, NW New Mexico, many in Central & W Colorado, NE Utah, A heavy cluster in Central & N Wyoming, a few in Montana and North Dakota. West Mexico and Canada also report finds.

If this find were confirmed as listed in the Smithsonian catalog it would be the first Mesonychid reported in Eastern North America.

As ever, there are problems. The matrix is reported as the McBean formation which was isn’t well covered in Georgia’s literature. In 1911 Veatch & Stephenson considered this a Middle Eocene, Claiborne Stage formation.

The Claiborne Stage is a regional term and if applied to the International Stratigraphic Chart is would in include the early-mid Lutetain Stage and early Bartonian Stage. This roughly dates the McBean Formation to between 46 and 39 million years old.

That’s a far cry from the 55.4 to 50.3 mya (million years ago) that represents the Wasatchian Stage of NALMA. This is a problem which potential researchers would have to address.

The latest reference of the McBean Formation that the author is aware of comes from Richard Hulbert's paper introducing Georgiacetus vogtlensis as a genus & species.(A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale {Mammalia, Cetacea, Archaeoceti} and Associated Biota from Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry, and David P. Aleshire; Journal of Paleontology; September 1998)

In the Georgiacetus paper the following quote appears:

Lithology of the Blue Bluff unit.-All strata in the SRS/VEGP region biostratigraphically equivalent to the upper Lisbon Formation of the Gulf Coastal Plain were traditionally referred to the McBean Formation (e.g., Veatch and Stephenson, 1911; Cooke, 1943; Nystrom et al., 1991). Huddlestun and Hetrick (1986) greatly restricted the McBean geographically and considered it a member of the Lisbon Formation. They also recognized a second stratigraphic unit in the region, informally named the Blue Bluff unit, that was a lateral equivalent of their restricted McBean. Fallow and Price (1995) subdivided the traditional McBean into three formations, the Blue Bluff, Tinker, and Santee (Fig. 2). The Blue Bluff unit is present in the vicinity of the VEGP and produced the fossils described in this study.

...The most recent numeric estimates for the boundaries of NP16 are 43.4 to 40.4 Ma, and this zone is correlated with the late Lutetian and earliest Bartonian ages (Berggren et al., 1995).

There is also Sam Pickering’s 1970 Bulletin 81 of the Georgia Geologic Survey. (Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry & Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia)

McBean Formation quotes from Pickering (1970).

STRATIGRAPHY

McBean Formation

The Middle Eocene McBean Formation has been observed at only a few exposures in the area mapped, along drainage ditches in the new west quarry of the Clinchfield Penn-Dixie Portland

Cement Company (Currently the Cemex Plant). These sediments are lithologically and biostratigraphically similar to the type McBean Formation of east Georgia. The author regards the top of the McBean in the study area as the top of the highest bed of micaceous, lignitic silt. Herrick (1961) referred to these sediments in the subsurface of Pulaski County as the Middle Eocene Lisbon Formation, an Alabama equivalent to the McBean.

BIOSTRATIGRAPHY

McBean Formation

The oyster, Ostrea sellaeform occurs near the top of the McBean Formation at the only outcrop observed. This oyster is regarded as being characteristic of Middle Eocene sediments wherever found (Veatch and Stephenson, 1911) (Cooke, 1943). The foraminifer Cibicides westi was found in drill cuttings from several of the Clinchfield Penn-Dixie Cement Company test holes by Herrick. It was found in material from the outcrop in the ditch at locality 11 by the author. Cibicides westi is regarded as being characteristic of Middle Eocene sediments wherever found (Herrick, 1961; Herrick and Vorhis, 1963).

PALEOECOLOGY

McBean Formation

The carbonaceous nature of the top of the McBean Formation and the presence of plant fossils and oysters indicate that the environment of deposition was probably quite near shore, and very possibly, in brackish water conditions. The abundant glauconite encountered further down in the formation in the test holes drilled at Clinchfield is an indicator of reducing conditions.

Our potential Mesonychid cries out for further research, a single partial femur isn’t much material to work with but if it can be confirmed to the level of Order or Family it would still represent a significantly important find certainly worthy of scientific publication and inclusion into the Paleobiology Database.

STRATIGRAPHY

McBean Formation

The Middle Eocene McBean Formation has been observed at only a few exposures in the area mapped, along drainage ditches in the new west quarry of the Clinchfield Penn-Dixie Portland

Cement Company (Currently the Cemex Plant). These sediments are lithologically and biostratigraphically similar to the type McBean Formation of east Georgia. The author regards the top of the McBean in the study area as the top of the highest bed of micaceous, lignitic silt. Herrick (1961) referred to these sediments in the subsurface of Pulaski County as the Middle Eocene Lisbon Formation, an Alabama equivalent to the McBean.

BIOSTRATIGRAPHY

McBean Formation

The oyster, Ostrea sellaeform occurs near the top of the McBean Formation at the only outcrop observed. This oyster is regarded as being characteristic of Middle Eocene sediments wherever found (Veatch and Stephenson, 1911) (Cooke, 1943). The foraminifer Cibicides westi was found in drill cuttings from several of the Clinchfield Penn-Dixie Cement Company test holes by Herrick. It was found in material from the outcrop in the ditch at locality 11 by the author. Cibicides westi is regarded as being characteristic of Middle Eocene sediments wherever found (Herrick, 1961; Herrick and Vorhis, 1963).

PALEOECOLOGY

McBean Formation

The carbonaceous nature of the top of the McBean Formation and the presence of plant fossils and oysters indicate that the environment of deposition was probably quite near shore, and very possibly, in brackish water conditions. The abundant glauconite encountered further down in the formation in the test holes drilled at Clinchfield is an indicator of reducing conditions.

Our potential Mesonychid cries out for further research, a single partial femur isn’t much material to work with but if it can be confirmed to the level of Order or Family it would still represent a significantly important find certainly worthy of scientific publication and inclusion into the Paleobiology Database.

Georgia’s Oldest Mammals

Here we have two finds resting in the Smithsonian which need attention. Georgia owes a debt of gratitude to the Smithsonian for keeping these specimens safe for so many decades. It’s my hope that a professional Georgia researcher will turn their eyes to Washington and unravel these mysteries once and for all.

Here we have two finds resting in the Smithsonian which need attention. Georgia owes a debt of gratitude to the Smithsonian for keeping these specimens safe for so many decades. It’s my hope that a professional Georgia researcher will turn their eyes to Washington and unravel these mysteries once and for all.