15E: The Curious

Steinkern Sea Biscuits

of Red Dog Farm Road

Posted by

Thomas Thurman

29/Aug/2020

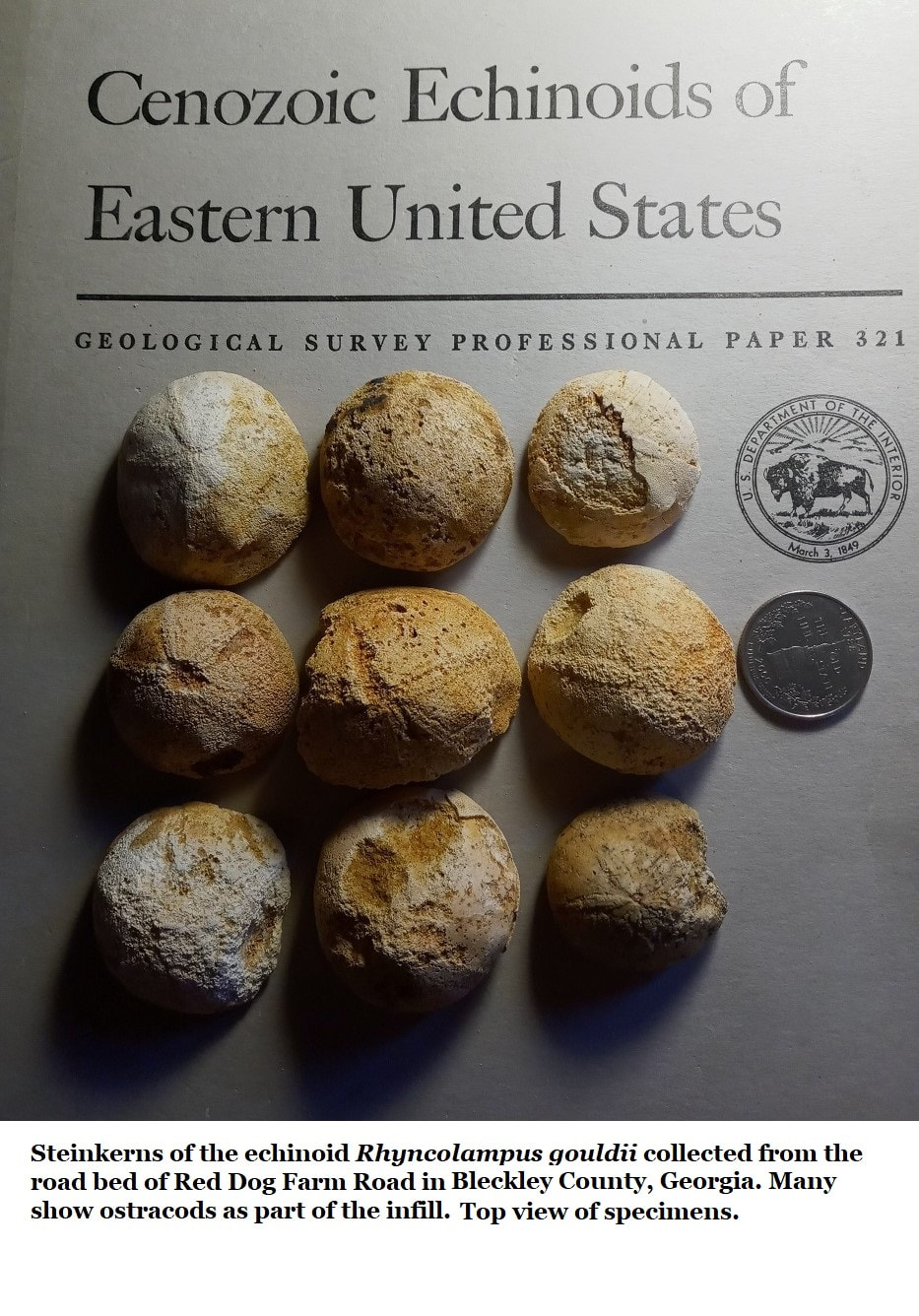

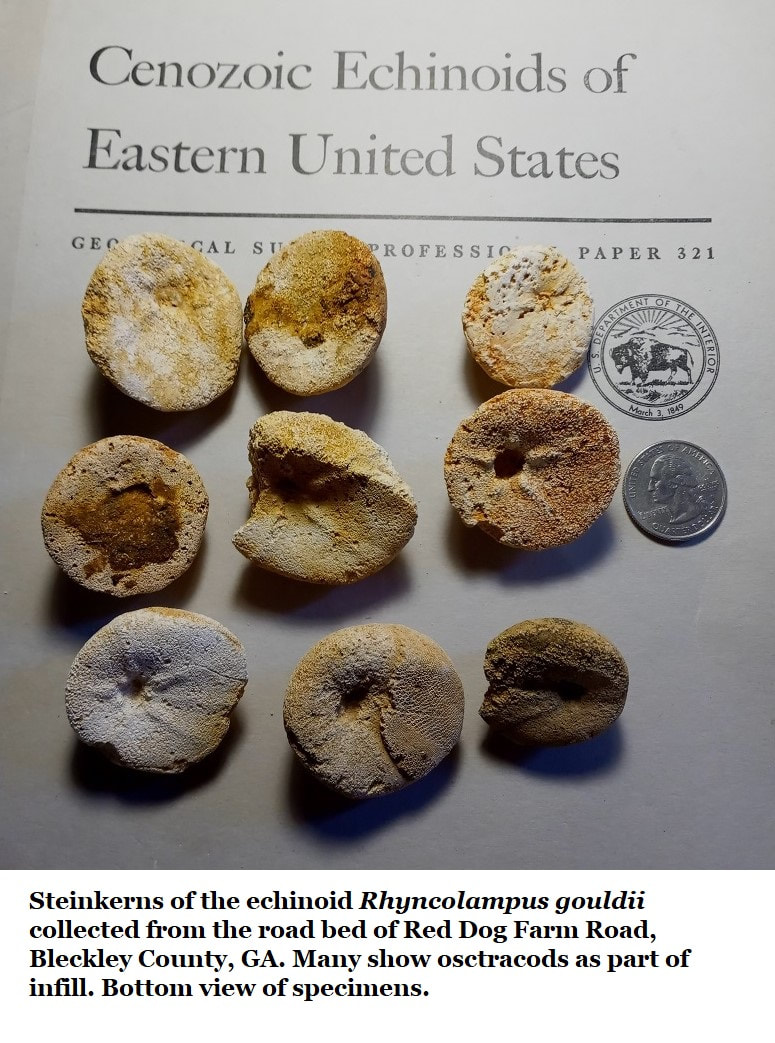

Fossiliferous rubble occurs in the roadbed of Bleckley County’s Red Dog Farm Road.

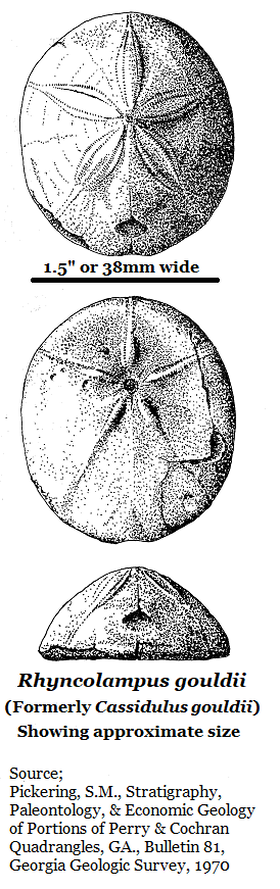

Among this rubble you’ll find steinkerns of the Early Oligocene sea urchin, or sea biscuit, Rhyncolampus gouldii. There isn’t a wealth of specimens, but they’re there. Exactly how and when these came to be here is something of a mystery.

Among this rubble you’ll find steinkerns of the Early Oligocene sea urchin, or sea biscuit, Rhyncolampus gouldii. There isn’t a wealth of specimens, but they’re there. Exactly how and when these came to be here is something of a mystery.

A “steinkern” is an internal cast, in this case of a sea urchin (1).

- The sea urchin dies, ostracods and other small scavengers enter the shell and fed on the soft parts. The urchin was buried in the sediments, which hardened.

- This become the matrix.

- Over time the calcium carbonate test ( shell) of the urchin itself dissolved and left a cavity, or internal mold, with openings where the mouth and anus had been.

- Sediments entered the filled the internal mold and hardened.

- Lastly, the surrounding matrix weathers away leaving the urchin’s steinkern, or internal cast, exposed for the fossil hunter to pick-up

The odd part is, these particular steinkerns occur nowhere else that I'm aware of, and I know the area moderately well.

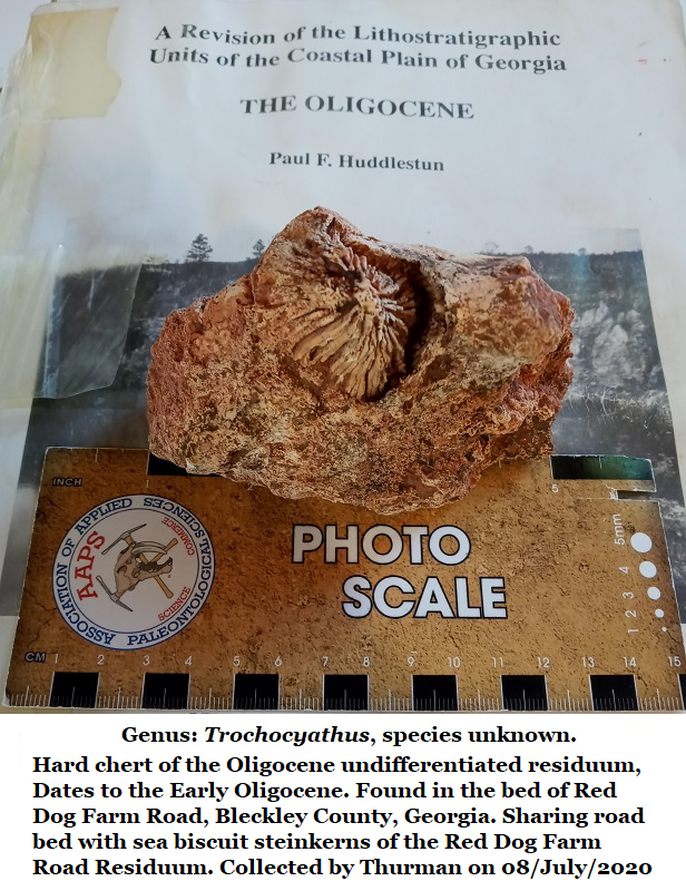

Additionally, the sediments which produce them is physically different than the hard, enduring chert of the Early Oligocene undifferentiated residuum (See Section 15C of the website) which surrounds the urchin's sediments (2,Pg.26).

This very same species of sea biscuit, Rhyncolampus gouldii, also occurs (rarely) in that undifferentiated residuum.

Additionally, the sediments which produce them is physically different than the hard, enduring chert of the Early Oligocene undifferentiated residuum (See Section 15C of the website) which surrounds the urchin's sediments (2,Pg.26).

This very same species of sea biscuit, Rhyncolampus gouldii, also occurs (rarely) in that undifferentiated residuum.

All urchins, sand dollars and sea stars are related, they’re echinoids, meaning spiny skin. All of these sea biscuit steinkerns are silicified, as is their matrix.

This particular sea urchin, Rhyncolampus gouldii was reassigned from its old name of Cassidulus gouldii, and you’ll frequently see the old classification in historical text.

This particular sea urchin, Rhyncolampus gouldii was reassigned from its old name of Cassidulus gouldii, and you’ll frequently see the old classification in historical text.

Silicification, means transformed with silica which has typically been introduced by ground water.

This material started as limestone which was exposed to silica rich groundwater. The silica changes the limestone to chert which is impervious to the acids in groundwater.

Limestone, since it is made of calcium carbonate, is dissolved by even weak acid.

For the matrix and the steinkern to be equally silicified, the steinkern must have formed before the exposure to silica rich groundwater.

This material started as limestone which was exposed to silica rich groundwater. The silica changes the limestone to chert which is impervious to the acids in groundwater.

Limestone, since it is made of calcium carbonate, is dissolved by even weak acid.

For the matrix and the steinkern to be equally silicified, the steinkern must have formed before the exposure to silica rich groundwater.

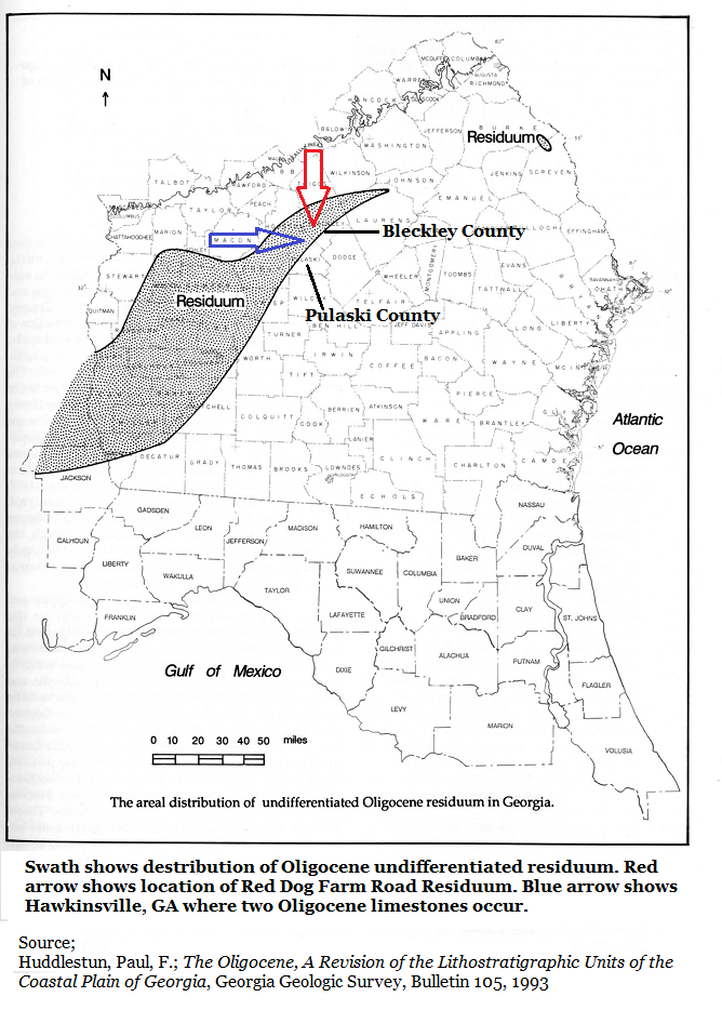

Sam Pickering, the former Georgia State Geologist who surveyed this area in 1970, referred to these sediments as the Flint River Formation (3,pg.16). Paul Huddlestun, who Pickering hired to do extensive research on Georgia’s Coastal Plain’s stratigraphy, reassign these sediments in 1993 as Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum (2,pg.25).

On 08/June/2020 Dr. Burt Carter, Professor of Paleontology at Georgia Southwestern State University and a long term echinoid researcher answered my questions about how the sea urchin’s calcium shell dissolved (4).

“I’m not absolutely positive why but the shell itself is always dissolved away in these chert molds around here. I suspect it has something to do with the exact chemistry of the shell vs the lime sediment around it. Most Cenozoic lime mud was originally aragonite and most other lime sediment was originally (and still is, unless silicified) lo-Mg calcite. Echinoderm tests (urchin shells) are high-Mg calcite, which is a little less soluble. So my hypothesis is that the aragonite and low Mg calcite were silicified and subsequently the test was leached away, still being high-Mg calcite. There are other possible hypotheses but that’s the one I like best.”

On 08/June/2020 Dr. Burt Carter, Professor of Paleontology at Georgia Southwestern State University and a long term echinoid researcher answered my questions about how the sea urchin’s calcium shell dissolved (4).

“I’m not absolutely positive why but the shell itself is always dissolved away in these chert molds around here. I suspect it has something to do with the exact chemistry of the shell vs the lime sediment around it. Most Cenozoic lime mud was originally aragonite and most other lime sediment was originally (and still is, unless silicified) lo-Mg calcite. Echinoderm tests (urchin shells) are high-Mg calcite, which is a little less soluble. So my hypothesis is that the aragonite and low Mg calcite were silicified and subsequently the test was leached away, still being high-Mg calcite. There are other possible hypotheses but that’s the one I like best.”

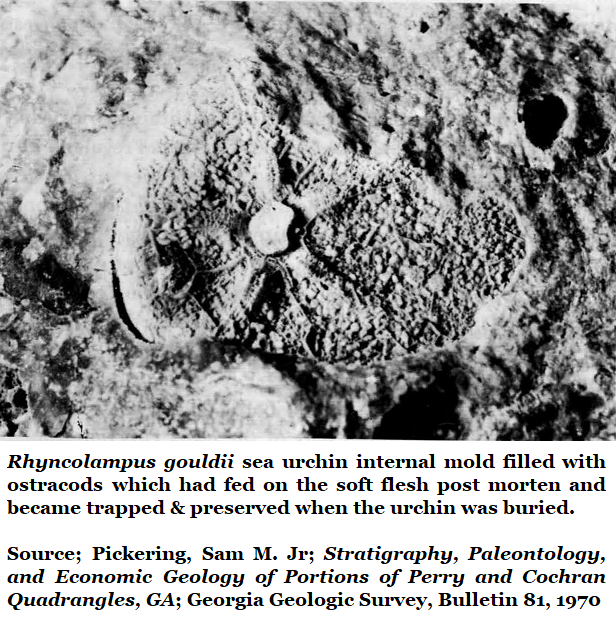

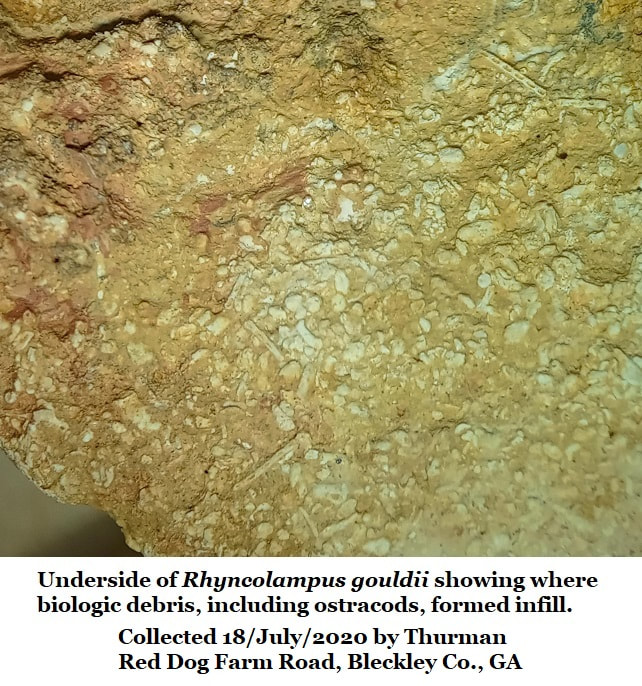

The material forming the steinkern, the material which filled the mold and hardened, looked like it contained bryozoans or other debris; maybe the urchins original spines? I asked Dr. Carter about this too…

“Without seeing the fossil I can’t be sure what the sand sized fossil grains are, or even if they are fossils. Bryozoans are pretty rare in most of the Oligocene rocks, so there may be some, but there might not. I’ve seen steinkerns that were virtually pure ostracods that probably swarmed in to feast on the dead tissues. It’s also possible that there are fecal pellets, which are common in limestone.”

“Without seeing the fossil I can’t be sure what the sand sized fossil grains are, or even if they are fossils. Bryozoans are pretty rare in most of the Oligocene rocks, so there may be some, but there might not. I’ve seen steinkerns that were virtually pure ostracods that probably swarmed in to feast on the dead tissues. It’s also possible that there are fecal pellets, which are common in limestone.”

I appreciate Carter’s advice and I’m reminded that in 1970 Sam Pickering, who went on to become the Georgia State Geologist, reported: “There is a definite association between the echinoid Rhyncolampus gouldii and various types of ostracods. Casts of this echinoid are often filled with ostracods, which are quite rare in the Flint River as a whole. Apparently, these echinoids died and ostracods entered their tests and fed on the interior soft parts until burial rendered their escape impossible.” (3,pg.36)

This particular species; Rhyncolampus gouldii (formerly Cassidulus gouldii) is an early Oligocene index fossil. It isn’t very common in Georgia, but in Florida’s Suwannee Limestone there are hosts of them.

This particular species; Rhyncolampus gouldii (formerly Cassidulus gouldii) is an early Oligocene index fossil. It isn’t very common in Georgia, but in Florida’s Suwannee Limestone there are hosts of them.

*

Paul F Huddlestun first reported the presence of these steinkerns in 1993 (2, Pg.25) when he found a single Rhyncolampus gouldii in this same location. However, at the time the find was attributed to the informal Shell Stone Creek Beds Formation which has since been abandoned as it couldn’t be confirmed in any reported location.

Paul F Huddlestun first reported the presence of these steinkerns in 1993 (2, Pg.25) when he found a single Rhyncolampus gouldii in this same location. However, at the time the find was attributed to the informal Shell Stone Creek Beds Formation which has since been abandoned as it couldn’t be confirmed in any reported location.

Wythe Cooke 1959

Sometimes it seems that nothing in science is simple, understanding a complex world can be challenging. The most influential & useful research paper over echinoids of the USA’s East Coast is Wythe Cooke’s 1959 report Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States. (5) It is rightfully considered an excellent identification and occurrence guide. But it desperately needs updating.

Cook’s 1959 report states that our heart urchin dates to the Middle Oligocene. (5,pg.4) Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern State University is a leading expert on echinoids and explains that Cooke was simply wrong about the age of the Suwannee Limestone, a common mistake at the time Cook’s work was published. Carter confirms that both the Suwannee Limestone and Rhyncolampus gouldii are Early Oligocene. (4)

The Tampa Bay Fossil Club states on their website that Rhyncholampas gouldi is by far the most common echinoid at Vulcan Mine, everyone finds a bucketful (6). They range in size from .5 inch to 2 inches across.

Sometimes it seems that nothing in science is simple, understanding a complex world can be challenging. The most influential & useful research paper over echinoids of the USA’s East Coast is Wythe Cooke’s 1959 report Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States. (5) It is rightfully considered an excellent identification and occurrence guide. But it desperately needs updating.

Cook’s 1959 report states that our heart urchin dates to the Middle Oligocene. (5,pg.4) Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern State University is a leading expert on echinoids and explains that Cooke was simply wrong about the age of the Suwannee Limestone, a common mistake at the time Cook’s work was published. Carter confirms that both the Suwannee Limestone and Rhyncolampus gouldii are Early Oligocene. (4)

The Tampa Bay Fossil Club states on their website that Rhyncholampas gouldi is by far the most common echinoid at Vulcan Mine, everyone finds a bucketful (6). They range in size from .5 inch to 2 inches across.

Echinoids in the Roadbed

Rhyncholampus gouldii isn’t the only echinoid in that roadbed. The sand dollar Clypeaster rogersi also occurs on the dirt road but they’re rare, very fragmentary molds or flat imprints. It takes a sharp eye to find one. However, there’s a roadcut wall nearby where you’ll find something else interesting, silicified, bioclastic chert dornicks.

Bioclastic simply means it’s made of biologic debris, bits of shell and microscopic life. A dornick is a hand sample, technically a rock whose size is suitable for throwing.

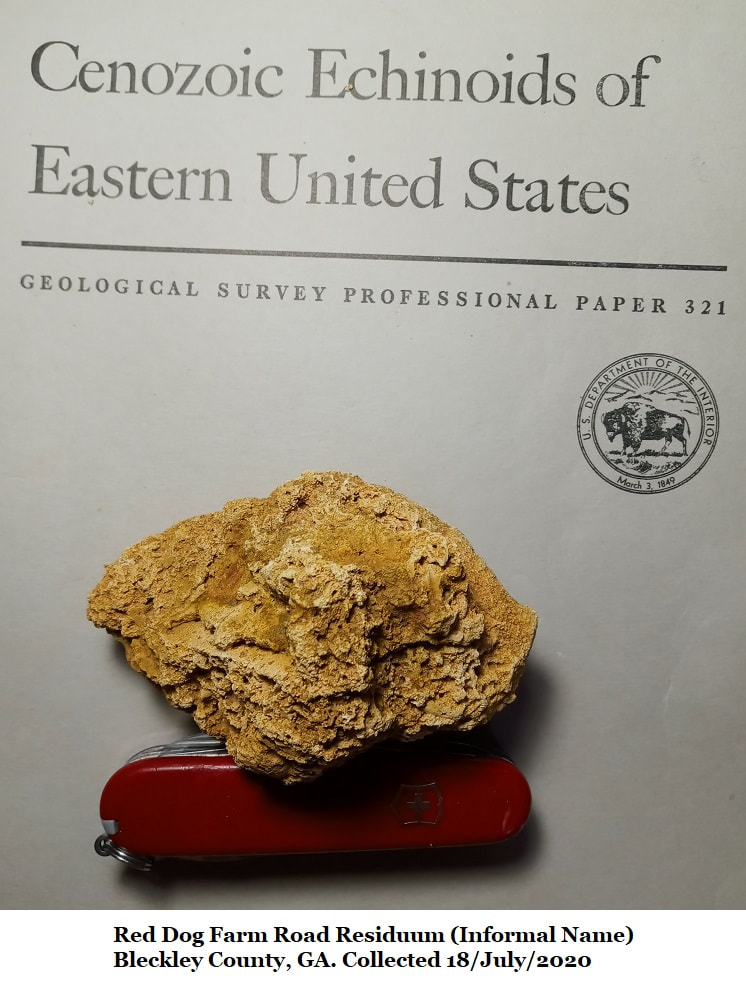

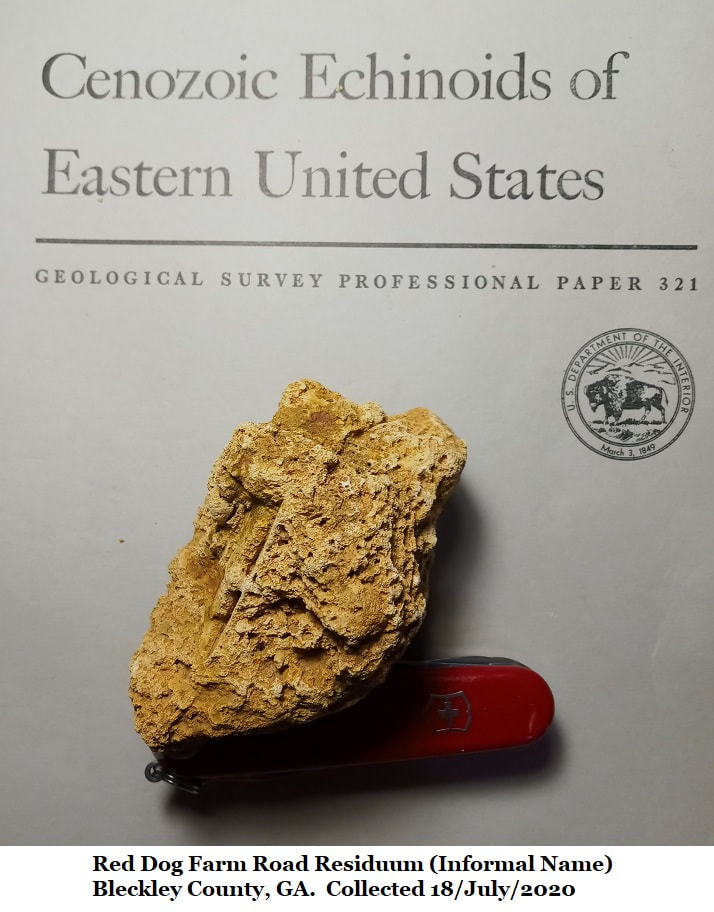

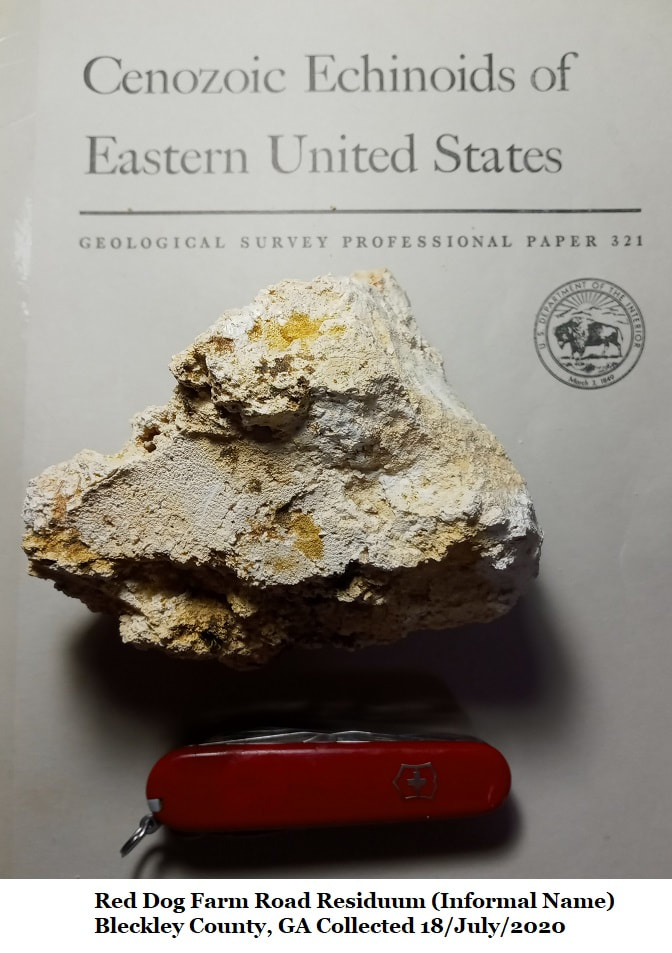

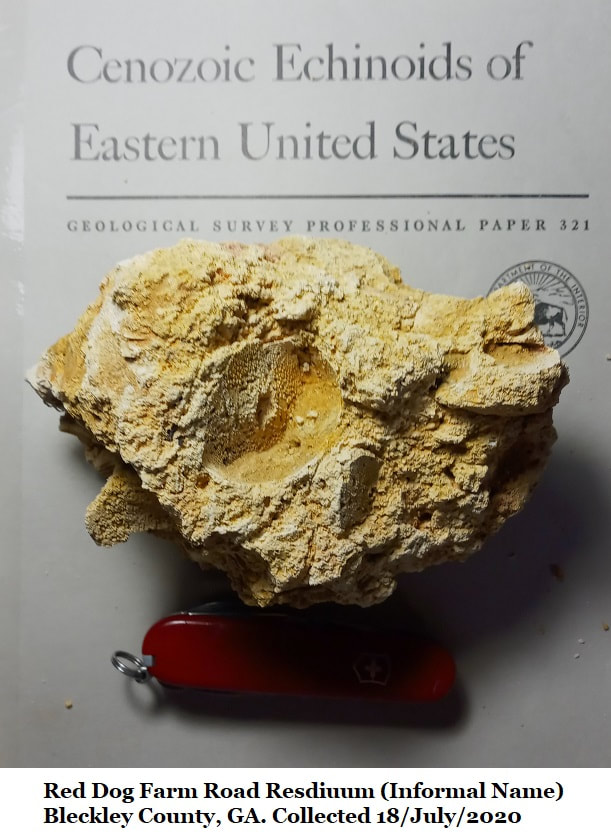

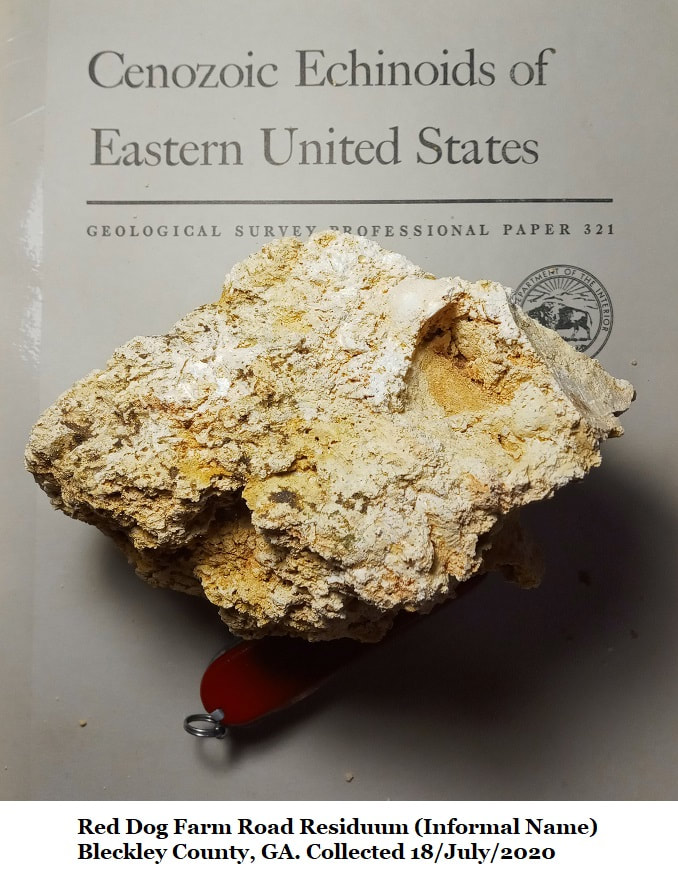

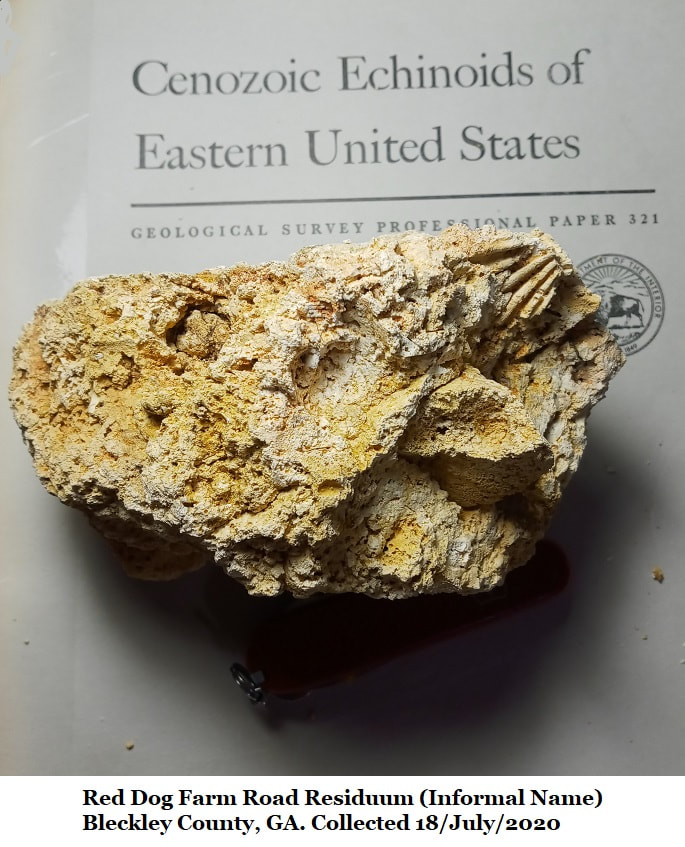

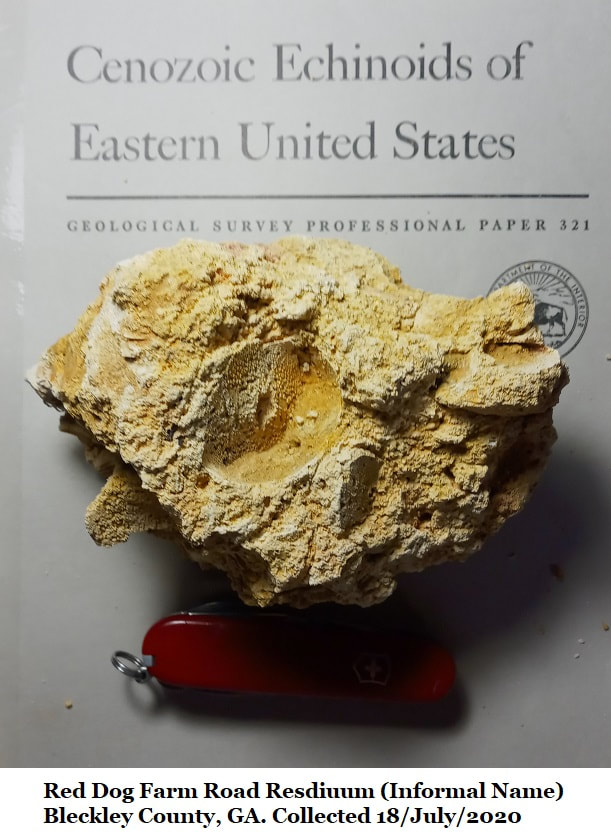

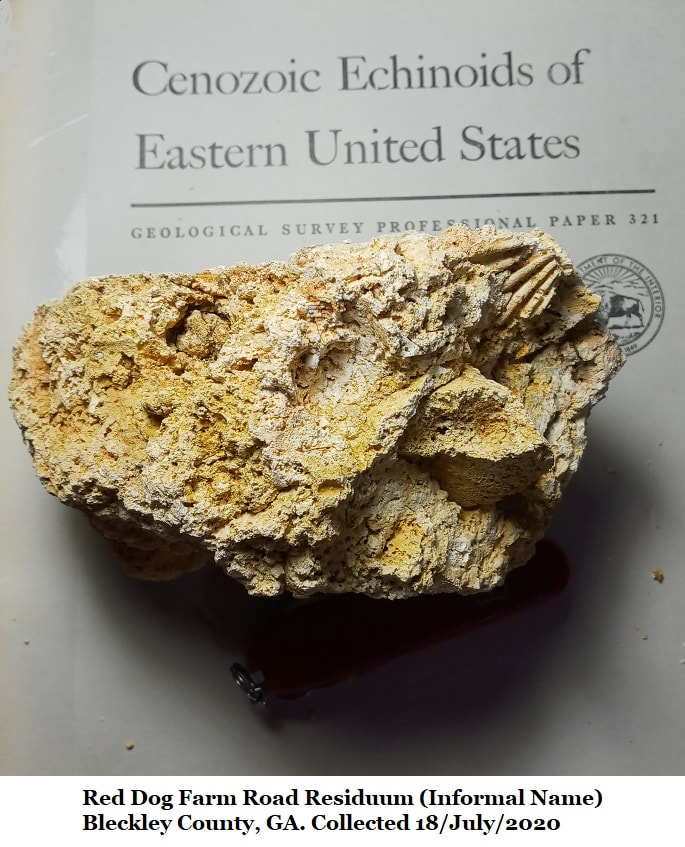

These dornicks from the roadcut wall often have heart urchins and fragmentary sand dollars in them. The rock is soft, rough textured, porous, crumbly, light blond colored chert. This is the residue of a once larger deposit. But we know very little about the original deposit. But, as residue, it fits the description of an Oligocene residuum. However, it is quite distinct from the hard chert designated as Oligocene undifferentiated residuum.

Rhyncholampus gouldii isn’t the only echinoid in that roadbed. The sand dollar Clypeaster rogersi also occurs on the dirt road but they’re rare, very fragmentary molds or flat imprints. It takes a sharp eye to find one. However, there’s a roadcut wall nearby where you’ll find something else interesting, silicified, bioclastic chert dornicks.

Bioclastic simply means it’s made of biologic debris, bits of shell and microscopic life. A dornick is a hand sample, technically a rock whose size is suitable for throwing.

These dornicks from the roadcut wall often have heart urchins and fragmentary sand dollars in them. The rock is soft, rough textured, porous, crumbly, light blond colored chert. This is the residue of a once larger deposit. But we know very little about the original deposit. But, as residue, it fits the description of an Oligocene residuum. However, it is quite distinct from the hard chert designated as Oligocene undifferentiated residuum.

Red Dog Farm Road Residuum

For the sake of this report, & simplicity, I’m going to refer to these dornicks as Red Dog Farm Road Residuum, this would be a very informal designation. In a moment we will be looking at the other Oligocene residuum.

The only known occurrence of the Red Dog Farm Road dornicks is a small, narrow lens suspended in a loamy greyish-brown soil which yield easily to tools. The lens may be 10 meters long and a hand span thick.

A systematic search for additional occurrences has not been performed.

For the sake of this report, & simplicity, I’m going to refer to these dornicks as Red Dog Farm Road Residuum, this would be a very informal designation. In a moment we will be looking at the other Oligocene residuum.

The only known occurrence of the Red Dog Farm Road dornicks is a small, narrow lens suspended in a loamy greyish-brown soil which yield easily to tools. The lens may be 10 meters long and a hand span thick.

A systematic search for additional occurrences has not been performed.

I mentioned softness; samples of the Red Dog Farm Road Residuum can be scratched with a fingernail. A fingernail has a hardness of 2.5 on Moh’s Scale. We call this chert because it is a silicified limestone that does not react to acid at all but just soaks it up like a sponge. Chert actually has a minimum hardness of 6.5 on Moh’s Scale.

The Red Dog Farm Road Residuum shows similar population concentrations of Rhyncholampus gouldii & Clypeaster rogersi. The C. rogersi, sand dollars, being flat and up to 7.6cm (3”) across were clearly more easily damaged and broken up than the little rounded urchins.

Even in the dornicks whole Clypeaster rogersi sand dollars weren’t observed. The two echinoids make up 80% of the identifiable populations. breaking down a softball sized sample yielded a couple of clams and a scattering of scallops, all were fragmentary. Scallops appeared to have a higher population. Two whole heart urchins were seen and an imprint from a third. One fragmentary sand dollar was observed and an impression of about 40% of another was seen. No gastropods. No bryozoans.

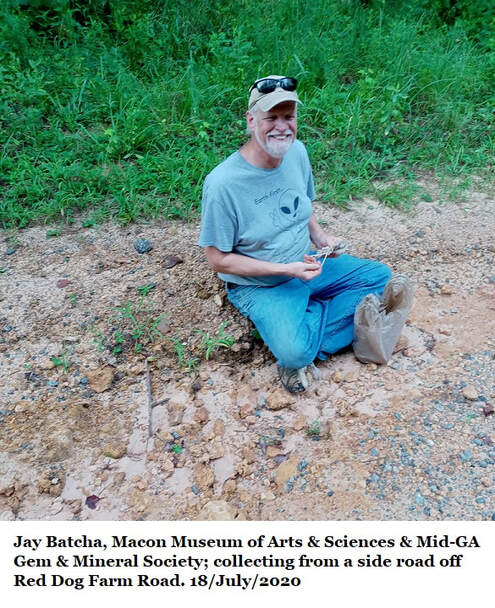

On 07/May/2017 Paul Huddlestun, Michael Reagin & myself visited Red Dog Farm Road and excavated samples of this material. Mr. Paul, who now lives in New Mexico, returned home and I shipped a sample for him to review.

Even in the dornicks whole Clypeaster rogersi sand dollars weren’t observed. The two echinoids make up 80% of the identifiable populations. breaking down a softball sized sample yielded a couple of clams and a scattering of scallops, all were fragmentary. Scallops appeared to have a higher population. Two whole heart urchins were seen and an imprint from a third. One fragmentary sand dollar was observed and an impression of about 40% of another was seen. No gastropods. No bryozoans.

On 07/May/2017 Paul Huddlestun, Michael Reagin & myself visited Red Dog Farm Road and excavated samples of this material. Mr. Paul, who now lives in New Mexico, returned home and I shipped a sample for him to review.

He sent me this 12/June/2017 report on Red Dog Farm Road Residuum:

For your records, I scrubbed the chert samples you sent me with a toothbrush and water to get rid of all the extraneous material adhering to the surface. I found that most of the chert was essentially sand-free except for perhaps a stray fine-grained sand. The chert matrix had the appearance of having been formed from fine bioclastic debris in apparent random orientation except that all the “bioclastic” particles could not be identified as to origin because of silicification and loss of original surface details. I did see what appears to be the silicified remains of a Clypeaster rogersi. It is certainly a sand dollar and it has the correct outline for a Clypeaster rogersi and not a Periarchus quinquefarius. There are also what appears to be veins of coarse grained, poorly sorted sand in the chunks of chert. These quartz sand concentrations appear to be 2-dimensional and not small lenses or pods enveloped within the chert. I would expect the later distribution if the poorly sorted sand was originally incorporated into the limestone/chert in a disturbance event. I often see in impure limestones and dolostones. It appears the coarse sand migrated downward along veins into the limestone/chert during the subaerial weathering process that resulted in the silicification of the original limestone. It also suggests that the Miocene Altamaha Formation originally overlay the Oligocene limestone in the Red Dog Road area. It is curious that the matrix of the chert, given that it was once formed from bioclastic debris, appears to be unlike the lithology of the Marianna and Glendon Limestones on the Ocmulgee River at Hawkinsville.

.....Paul F. Huddlestun

So, while the Red Dog Farm Road material is certainly residuum, it is distinct from the Oligocene undifferentiated residuum, and the Marianna & Glendon limestones of nearby Pulaski County.

Not The Shellstone Creek Bed Formation

At first I'd believed we'd found the informal formation Shellstone Creek Beds which Huddlestun had reported in 1993 (2,pg.21). But Mr. Paul himself confirmed that the Red Dog Farm Road Residuum was separate and distinct from what he'd reported in 1993. He further agreed that since the ShellStone Creek Bed formation could not be identified in any of the three localities he'd originally reported, it must be abandoned.

For your records, I scrubbed the chert samples you sent me with a toothbrush and water to get rid of all the extraneous material adhering to the surface. I found that most of the chert was essentially sand-free except for perhaps a stray fine-grained sand. The chert matrix had the appearance of having been formed from fine bioclastic debris in apparent random orientation except that all the “bioclastic” particles could not be identified as to origin because of silicification and loss of original surface details. I did see what appears to be the silicified remains of a Clypeaster rogersi. It is certainly a sand dollar and it has the correct outline for a Clypeaster rogersi and not a Periarchus quinquefarius. There are also what appears to be veins of coarse grained, poorly sorted sand in the chunks of chert. These quartz sand concentrations appear to be 2-dimensional and not small lenses or pods enveloped within the chert. I would expect the later distribution if the poorly sorted sand was originally incorporated into the limestone/chert in a disturbance event. I often see in impure limestones and dolostones. It appears the coarse sand migrated downward along veins into the limestone/chert during the subaerial weathering process that resulted in the silicification of the original limestone. It also suggests that the Miocene Altamaha Formation originally overlay the Oligocene limestone in the Red Dog Road area. It is curious that the matrix of the chert, given that it was once formed from bioclastic debris, appears to be unlike the lithology of the Marianna and Glendon Limestones on the Ocmulgee River at Hawkinsville.

.....Paul F. Huddlestun

So, while the Red Dog Farm Road material is certainly residuum, it is distinct from the Oligocene undifferentiated residuum, and the Marianna & Glendon limestones of nearby Pulaski County.

Not The Shellstone Creek Bed Formation

At first I'd believed we'd found the informal formation Shellstone Creek Beds which Huddlestun had reported in 1993 (2,pg.21). But Mr. Paul himself confirmed that the Red Dog Farm Road Residuum was separate and distinct from what he'd reported in 1993. He further agreed that since the ShellStone Creek Bed formation could not be identified in any of the three localities he'd originally reported, it must be abandoned.

The traditional Oligocene undifferentiated residuum

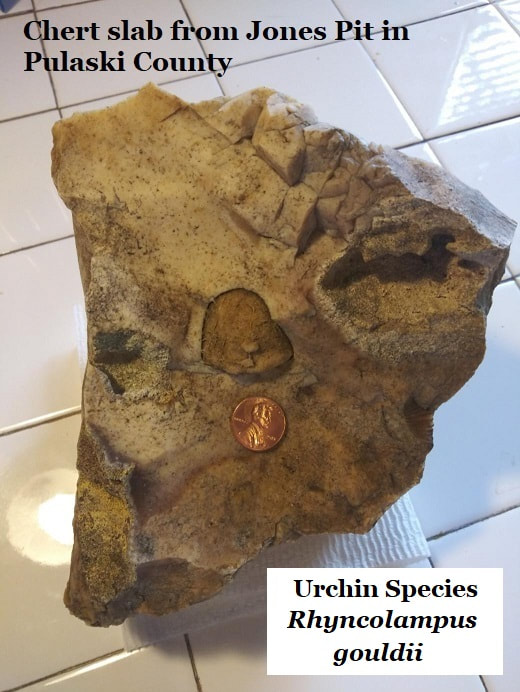

I began this page with a mention of fossiliferous rubble in the bed of Red Dog Farm Road. There are indeed urchin steinkerns in of the Red Dog Farm Road Residuum. However; the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum, as described by Huddlestun 1993 (5,Pg.25), is also present in the roadbed rubble as dornicks and pebbles, often with fossils.

Fossiliferous Oligocene undifferentiated residuum, even as rubble, is very common in Houston, Bleckley & several other South Georgia counties. It can be prevalent to the point of being a nuisance for farmers and gardeners. But Rhyncolampus gouldii & Clypeaster rogersi is somewhat rare in this dense, hard chert. It is known for large populations of bivalves, and in some locations you can see large forams, but there will be few species of either present. A few scallops occur, a few gastropods, and rarely you’ll see a solitary coral. It is described more fully in the website’s Section 15C; Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum. The general description of fossil content for the Oligocene undifferentiated residuum in the literature is high density but low diversity.

Chert is a form of quartz and it can be very hard, coming in on Mohs’ hardness scale at 6.5 to 7. This chert does not absorb liquids, acids, water, or anything. A good conchoidal fracture will be textured smooth as glass. Audubon’s field guide (1988) correctly describes chert as; extremely hard, rough, and dense. Strongly resistant to erosion…

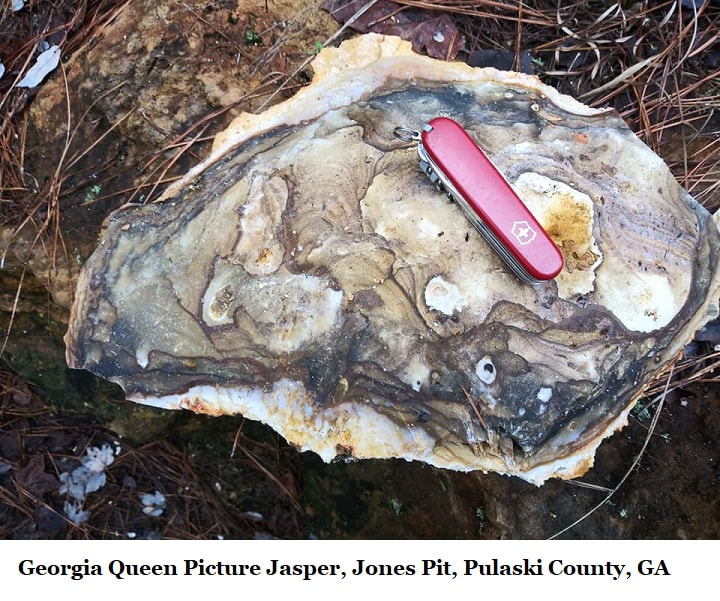

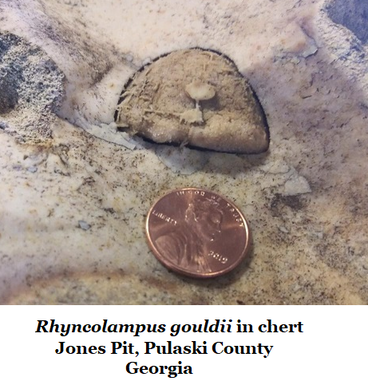

Jones Pit in Pulaski County is a dig location for the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society. Its found beside the old Chandler Iron Mine. It is one of the very few places you can find the beautiful Georgia Queen Picture Jasper. This jasper is part of Oligocene residuum boulders. Chalcedony, another gem variety of chert, is also present.

This chert is hard, I’ve had my 16 ounce crack hammer ring like a bell as it bounced off after a hard smack. It didn’t even make a mark but left my hand stinging. The fact that it occurs near an iron deposit explains the rich coloration.

Jones Pit in Pulaski County is a dig location for the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society. Its found beside the old Chandler Iron Mine. It is one of the very few places you can find the beautiful Georgia Queen Picture Jasper. This jasper is part of Oligocene residuum boulders. Chalcedony, another gem variety of chert, is also present.

This chert is hard, I’ve had my 16 ounce crack hammer ring like a bell as it bounced off after a hard smack. It didn’t even make a mark but left my hand stinging. The fact that it occurs near an iron deposit explains the rich coloration.

Jones Pit has produced more Rhyncolampus gouldii heart urchins than any site I’m aware of beside the Red Dog Farm Road Residuum. The urchins from Jones Pit are also far better preserved. They’ll sometimes be deep inside a boulder when you bust it open. in the sample imaged above you can see preserved burrows on the outside of the urchins where scavangers fed on the deceased animal.

But these steinkerns aren't common. I’m aware of maybe twenty individuals found in a dozen years, and three of those were in a single basketball sized boulder.

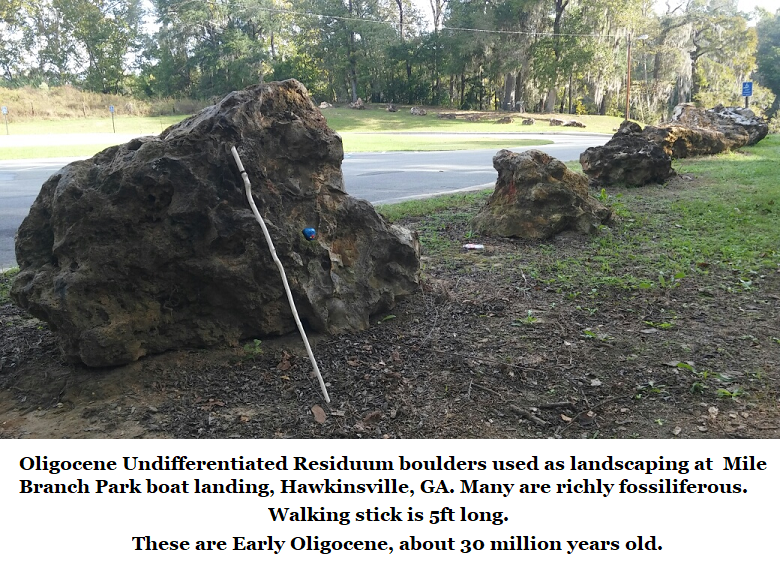

Go to Hawkinsville’s Mile Branch Park boat ramp and there are dozens of large Oligocene residuum boulders used as landscaping. Though not as lovely as the Georgia Queen Jasper, it is similar in hardness and density. It is often highly fossiliferous, colorful and occasionally translucent.

But these steinkerns aren't common. I’m aware of maybe twenty individuals found in a dozen years, and three of those were in a single basketball sized boulder.

Go to Hawkinsville’s Mile Branch Park boat ramp and there are dozens of large Oligocene residuum boulders used as landscaping. Though not as lovely as the Georgia Queen Jasper, it is similar in hardness and density. It is often highly fossiliferous, colorful and occasionally translucent.

Comparison of The Two Oligocene Residuums

Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum

Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum

- Moderately widespread and well known.

- Does not react to acid.

- Hard, dense, conchoidal fracture, and often highly fossiliferous.

- Known to have high populations of bivalves with little diversity.

- At least two species of forams present; Lepidocyclina undosa & Lepidocyclina favosa

- At least two species of echinoids are present, but populations are sparse & highly localized; Rhyncolampus gouldii & Clypeaster rogersi

- Very resistant to weathering.

- Very limited in occurrence

- Currently known only from Red Dog Farm Road.

- Does not react to acids.

- Soft, can be scratched with a fingernail.

- Fossils in all orientations, suggesting high energy current.

- Fossils typically fragmentary, again suggesting high energy current.

- Very susceptible to weathering.

- Echinoids common but other fossils are less pervelant.

- Relatively high populations of Rhyncolampus gouldii & Clypeaster rogersi

- A typical hand sample will have multiple individuals.

Oligocene Limestones on the Northern Coastal Plain

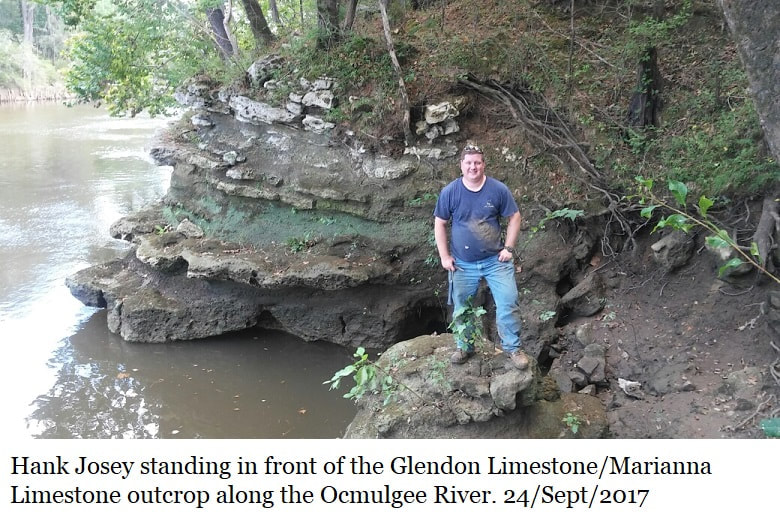

Just 19 kilometers (12 miles) south of Bleckley County's Red Dog Farm Road Residuum you'll find two distinct Early Oligocene Limestones in Pulaski County. Both can be found south of the Miles Branch Part Boat Landing.

The Marianna Limestone occurs in the bed of Mile Branch Creek, about 200 yards south of the boat ramp; see Section 15A of the website.

The Glendon Limestone occurs on the west bank of the Ocmulgee River about a mile south of the boat ramp, see Section 15B of this website.

The Confusing Early Oligocene

I personally struggle to understand how these four distinct Early Oligocene deposits formed on Georgia's northern Coastal Plain.

- The vast spread of chert boulders & dornicks of Oligocene undifferentiated residuum, it's Oligocene fossils are all Early Oligocene. The "undifferentiated" part refers to the very limited presence of both Late Eocene & Miocene cherty fossils which got mixed in when the limestone beds collapsed.

- The Marianna Limestone

- The Glendon Limestone

- Now the (informal) Red Dog Farm Road Residuum.

There are even other Early Oligocene deposits in South Georgia.

As much as I hate to admit it, I have neither theory nor explanation for this mystery. Early Oligocene conditions in Georgia are complex, . There was large scale erosion and secondary deposition after the Oligocene which we only partially understand.

Dear Georgia; please invest in further Natural History research.

If a professional research wishes to review these deposits I would be happy to offer my services as a field guide.

*

This little article is dedicated to

Sam M. Pickering Jr.

Scientist &

Former Georgia State Geologist

Born 10/January/1938

Passed 28/August/2020

*

It was Pickering who led the 1976 Georgia Geologic Map Project

& initiated the most wide-ranging and in depth

field research program Georgia has ever seen.

*

References:

- Carter, Burt; Personal communication explaining the formation of steinkerns.

- Huddlestun, Paul F.; The Oligocene, A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 105, 1993

- Pickering, Sam M. Jr; Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, GA; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 81, 1970

- Carter, Burt; Personal Communication; Rhyncolampus gouldii is Early to mid-Oligocene. Wythe was wrong about the age of the Suwannee Limestone. There is no formal middle Oligocene stage. The Suwannee is considered early, Rupelian Stage., 02/Aug/2020

- Cooke, C. Wythe; Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States, Geological Survey Professional Paper 321, USGS, 1959

- TampaBayFossilClub.com; Echinoids at Vulcan Mine