20J; Watkins Quarry

Pleistocene Vertebrates,

Glynn County, GA

By Thomas Thurman

25/November/2020

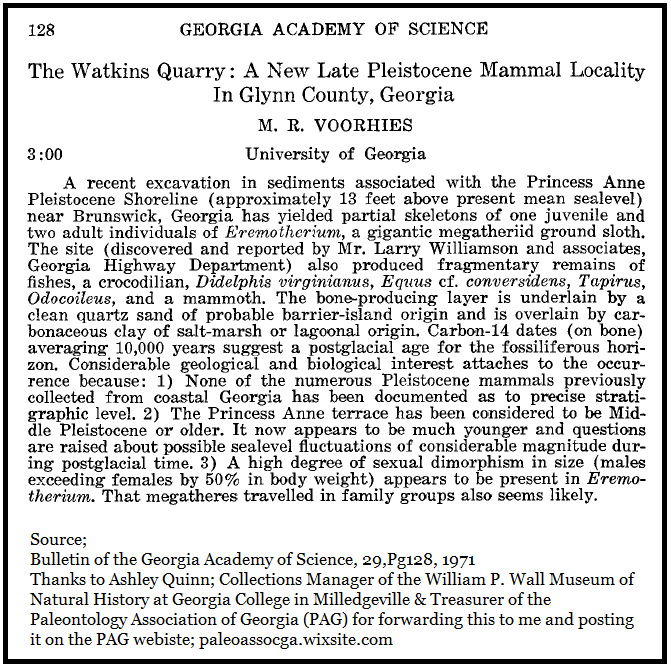

In 1971 Michael Voorhies, Professor of Paleontology at the University of Georgia, reported partial skeletons from one juvenile and two adult Eremotherium giant ground sloths from Watkins quarry in Glynn County, near Brunswick.(1) He additionally observes that these fossils are the first Pleistocene specimens whose stratigraphic horizon was known.

Brunswick has grown a bit since 1971.

Brunswick has grown a bit since 1971.

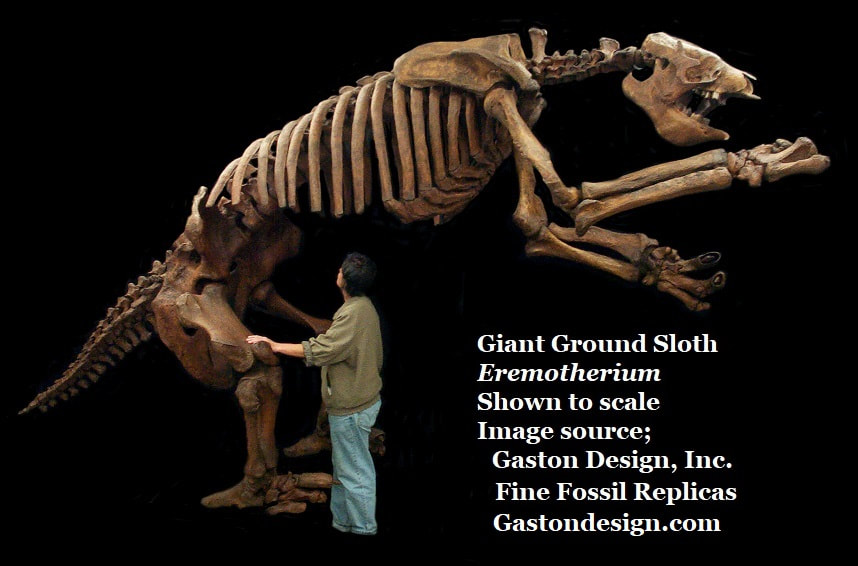

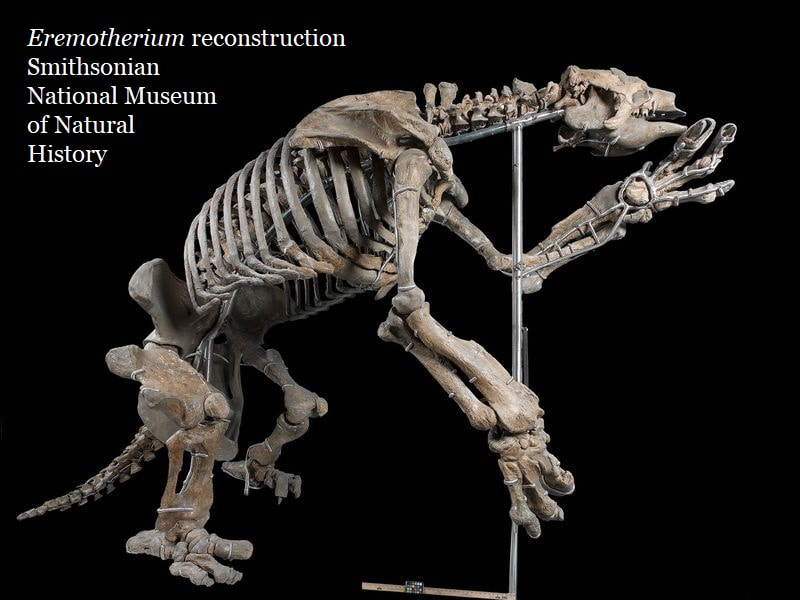

Eremotheriums were large Pleistocene animals, only the Columbian mammoth challenged them for sheer size. Their skeletal structure is massive. The bones of their forelimbs are the size of a man’s thigh. The front paw is the size of a man’s chest. Just a single claw can be the size of a man’s hand.

Also, there’s no reason to believe Eremotherium was a slow-moving animal like modern arboreal, tree dwelling sloths. As ground sloths they were vulnerable to the host of advanced predators roaming Georgia. There were American cheetahs (Felis inexpectata), jaguars (Panthera onca), cougars (Puma concolor) and roaming packs of grey wolves (Canis lupus) to name a few. Florida and some surrounding states have produced fossils from dire wolves (Canis dirus), red wolves (Canis rufus), the American lion (Panthera atrox) and even the saber-tooth tiger Smilodon fatalis, they likely hunted Georgia too. Still, sheer size was its main defense and since those huge claws seem evolved to rend trees, the animal was undoubtedly immensely strong.

Also recovered from Watkins quarry were remains from the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), the Mexican horse (Equus cf. conversidens), tapir (Tapirus), deer (Odocoileus), mammoth, crocodile and partial fish remains.

The precise location of Watkins quarry is unknown, but it is near the historic Brunswick-Altamaha Canal which was constructed between 1838-1839. The original construction of the canal produced a partial tooth which was given to the famous English geologist Charles Lyell in 1845 during his first visit to Georgia and was used to establish the Columbian Mammoth as a new species. (See Section 20A of this website) So the canal is forever wound into Georgia’s literature.

The precise location of Watkins quarry is unknown, but it is near the historic Brunswick-Altamaha Canal which was constructed between 1838-1839. The original construction of the canal produced a partial tooth which was given to the famous English geologist Charles Lyell in 1845 during his first visit to Georgia and was used to establish the Columbian Mammoth as a new species. (See Section 20A of this website) So the canal is forever wound into Georgia’s literature.

The site was discovered by Mr. Larry Williamson & associates of the Georgia Highway Department. Like Voorhies, we are grateful still that such a find was reported to science. Mr. William’s contribution will be remembered.

According to Voorhies the bone-producing layer is underlain by a clean quartz sand of probable barrier-island origin. The fossil bed is overlain by a carbonaceous clay of salt-marsh or lagoonal origin. In 1974 carbon dating gave an average of 10,000 years which suggests a post-glacial age for the fossil horizon.

According to Voorhies the bone-producing layer is underlain by a clean quartz sand of probable barrier-island origin. The fossil bed is overlain by a carbonaceous clay of salt-marsh or lagoonal origin. In 1974 carbon dating gave an average of 10,000 years which suggests a post-glacial age for the fossil horizon.

Clark Quarry, established as a research dig by Dr. Alfred Mead of Georgia College in Milledgeville (see Section 20A of this website) is also in the Brunswick area, adjacent to the Brunswick-Altamaha Canal and Mead states that Clark quarry was within 2km (1.2 miles) of Voorhies’ 1971 Watkins Quarry.(2) Clark quarry also produced wonderful fossils from several species.

Alfred Mead, like Voorhies before him, identified the fossil bearing bed as the Princess Anne Terrace of the Satilla Formation. However, Mead’s description is a little different. “The fossiliferous horizon at Clark Quarry is approximately one meter thick and composed of a sell-sorted, sub rounded to subangular, medium to coarse grained quartz sand lacking muddy sediment. Directly below this horizon is a marine sand layer containing fossil bivalves and gastropods.” (2,pg.174) Mead had dating tests performed on some of the remains his team recovered and the results showed them to be 21,000 years old.

Alfred Mead, like Voorhies before him, identified the fossil bearing bed as the Princess Anne Terrace of the Satilla Formation. However, Mead’s description is a little different. “The fossiliferous horizon at Clark Quarry is approximately one meter thick and composed of a sell-sorted, sub rounded to subangular, medium to coarse grained quartz sand lacking muddy sediment. Directly below this horizon is a marine sand layer containing fossil bivalves and gastropods.” (2,pg.174) Mead had dating tests performed on some of the remains his team recovered and the results showed them to be 21,000 years old.

Assuming Voorhies & Mead were working the same fossil bed in locations separated by 2 kilometers and near the historic canal, we can assume that the fossil bed is fairly widespread. Voorhies states that the fossils came from a layer just above the bed of quartz sand. Mead reports that this 1 meter thick quartz sand bed was the fossiliferous horizon. We know, without doubt, that Mead was present and that his team had to physically dig down to the bone producing layer. With this in mind it would seem Mead’s report would be more accurate.

Voorhies may have been relying on reports from a Georgia Highway Department road crew, not to doubt their observations but they were working behind heavy equipment cutting a road. It’s possible that the fossil bed had been disturbed by the time the road crew noticed the bones.

Voorhies may have been relying on reports from a Georgia Highway Department road crew, not to doubt their observations but they were working behind heavy equipment cutting a road. It’s possible that the fossil bed had been disturbed by the time the road crew noticed the bones.

Dr. Robert K. McAfee (A rocking slothologist) is indeed an expert on sloths. He’s an Assistant Professor of Anatomy at PCOM (Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine) in Suwannee, Georgia. McAfee is deeply immersed in the science of sloths… He reports that research from South America looked at sexual dimorphism in Eremotherium, but that sexes are rarely assigned to specimens. However, in many modern members of the Xenarthra clade, including sloths, the females are larger. (Personal communication)

No further research has emerged showing that groups or giant ground sloths moved together.

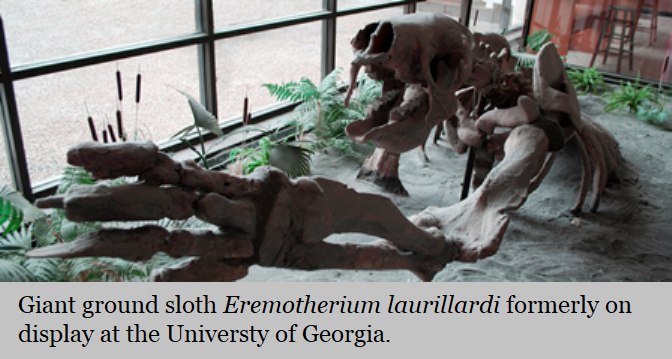

While most of the fossils Voorhies collected and added to the UGA collection have been lost, one of the Eremotheriums was on display, until recently, at the university. It has since been taken down and put into storage.

While most of the fossils Voorhies collected and added to the UGA collection have been lost, one of the Eremotheriums was on display, until recently, at the university. It has since been taken down and put into storage.

References:

- Voorhies; M.R.; The Watkins Quarry, A New Late Pleistocene Mammal Locality in Glynn County, Georgia; Bulletin of the Georgia Academy, 29, Pg128, 1971

- Mead, Alfred J.; Bahn, Robert A.; Chandler, Robert M.; Parmley, Dennis; Preliminary Comments on the Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Clark Quarry, Brunswick, Georgia. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates, Vol.23. Pg. 174-176, 2006

- Huddlestun, Paul F.; The Miocene Through Holocene, A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Georgia Coastal Plain, Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 104, 1988.

This report and many more are available at

RESOURCES | paleoassocga (wixsite.com)

RESOURCES | paleoassocga (wixsite.com)