27B: Georgia’s Lost Meteorite

The Pulaski County Iron

By

Thomas Thurman

GeorgiasFossils.com

Filed on 11/Oct/2020

We need to find a lost meteorite.

Do you happen know a Mr. John Peterson that lived in Hapeville, Georgia during the mid 1950s? Maybe his family?

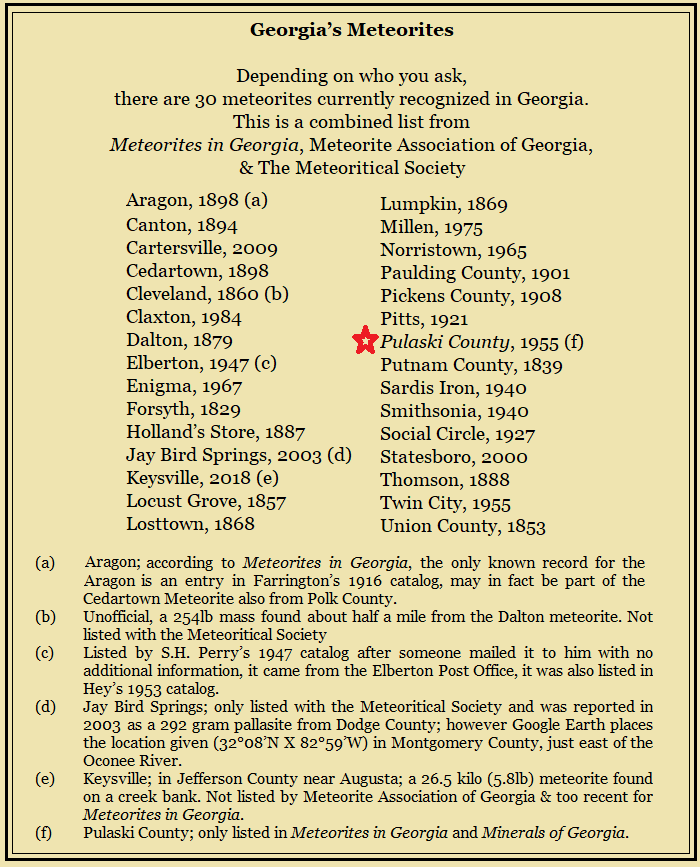

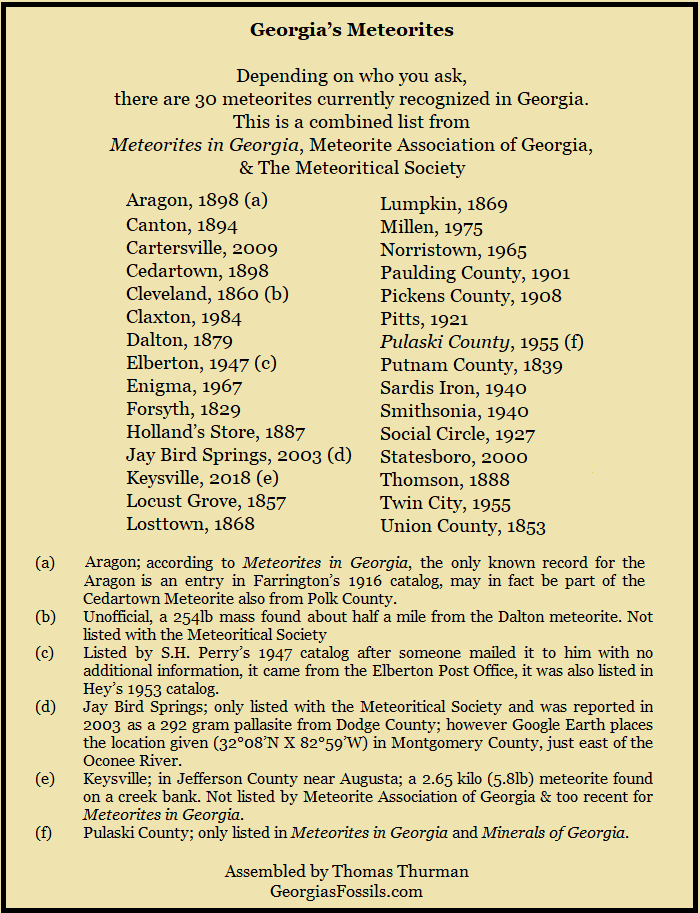

The fun of exploring Georgia’s natural history is its wealth of true stories, many of which haven’t been heard by most Georgians. Some of which, like the history of the lost Pulaski County iron meteorite, are unexplained errors which have stood uncorrected for decades. You can quickly progress from a good story to a straight up mystery that begs to be resolved. Fortunately, in the case of the Pulaski Iron all the information necessary to correct the official record is at hand.

My interest in the Pulaski County meteorite was first aroused in 2010, I did initial research and wrote a little piece for the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society newsletter, Gemclips. Here I have expanded that into the more fully referenced and researched piece below, maybe its enough to correct the record.

The Pulaski Iron

In the autumn of 1955, Mr. John Peterson of Hapeville Georgia brought a 116 gram (4oz) iron to the offices of the Georgia Geologic Survey. He’d found it in a Pulaski County pasture just southwest of Hawkinsville. A.S. Furcron, the Survey’s meteorite expert, recognized it as a possible meteorite and with Peterson’s permission sent it to the U.S. National Museum (Smithsonian) to be confirmed and compared with other iron meteorites from Georgia, specifically the Sardis Iron which was geographically the closest find and in the museum’s collection. (1,pg.129) Furcron wondered if Peterson’s specimen might be a fragment of the Sardis iron which broke off during flight.

In the autumn of 1955, Mr. John Peterson of Hapeville Georgia brought a 116 gram (4oz) iron to the offices of the Georgia Geologic Survey. He’d found it in a Pulaski County pasture just southwest of Hawkinsville. A.S. Furcron, the Survey’s meteorite expert, recognized it as a possible meteorite and with Peterson’s permission sent it to the U.S. National Museum (Smithsonian) to be confirmed and compared with other iron meteorites from Georgia, specifically the Sardis Iron which was geographically the closest find and in the museum’s collection. (1,pg.129) Furcron wondered if Peterson’s specimen might be a fragment of the Sardis iron which broke off during flight.

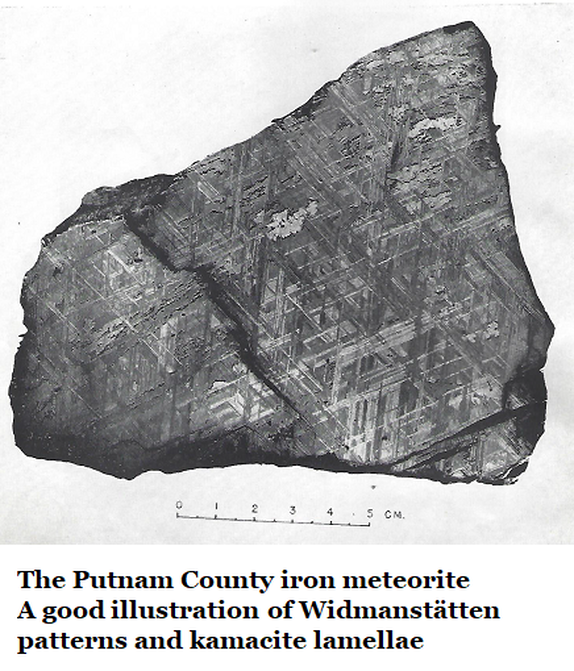

Peterson consented for one of the faces of the partially altered (rusted) meteorite to be polished. (1,pg129) The polished surface was then acid etched to reveal the Widmanstätten patterns (Thomson Structures) in the meteorite’s make-up. The meteorite was a typical iron/nickel alloy called kamacite; and the bands revealed by polishing & etching are call lamellae. These vary in width and form from one iron meteorite to another, much like a fingerprint.

The Pulaski iron was described as a coarse octahedrite with a few small cohenite inclusions that had an average kamacite lamellae bandwidth of 1.3mm. (1,pg.129) These things prove important to resolving our mystery.

Sadly, no known images exist of the Pulaski iron. Neither is there any record of its dimensions or rough shape. However, in Robert B. Cook’s 1978 Minerals of Georgia, the specimen is referred to as a fragment (3,pg.16). So perhaps it looked like part of another body.

Sadly, no known images exist of the Pulaski iron. Neither is there any record of its dimensions or rough shape. However, in Robert B. Cook’s 1978 Minerals of Georgia, the specimen is referred to as a fragment (3,pg.16). So perhaps it looked like part of another body.

Both Meteorites in Georgia & Minerals of Georgia report the approximate location for the Pulaski County pasture as 32°15’N by 83°30’W, this location shows an elevation of 279ft. Since both publications come from the Georgia geologic Survey, the authors were likely referencing the same original report.

Last Record

The U.S. National Museum confirmed the Pulaski as a meteorite un-related to the Sardis, then they dropped their investigation and returned the small iron to the Georgia Geologic Survey, who passed it back John Peterson. They informed Peterson of their findings, yes he’d found a real meteorite, and they requested that he look for and report any additional fragments.

However, Peterson lived in Hapeville, Georgia, near Atlanta. Hapeville is roughly 108 miles north of the Pulaski County pasture where he found the meteorite. There is no record of what Peterson’s relationship was to this location and he never reported another find.

It should also be noted that the report in Meteorites in Georgia was originally written two years after the specimen was returned to John Peterson (1957?), and neither Peterson nor the meteorite were never seen in the Survey again. The version reviewed here was published in 1966.

The U.S. National Museum confirmed the Pulaski as a meteorite un-related to the Sardis, then they dropped their investigation and returned the small iron to the Georgia Geologic Survey, who passed it back John Peterson. They informed Peterson of their findings, yes he’d found a real meteorite, and they requested that he look for and report any additional fragments.

However, Peterson lived in Hapeville, Georgia, near Atlanta. Hapeville is roughly 108 miles north of the Pulaski County pasture where he found the meteorite. There is no record of what Peterson’s relationship was to this location and he never reported another find.

It should also be noted that the report in Meteorites in Georgia was originally written two years after the specimen was returned to John Peterson (1957?), and neither Peterson nor the meteorite were never seen in the Survey again. The version reviewed here was published in 1966.

Local, Native, Terrestrial Iron

There is native, naturally occurring iron in Pulaski county at Jones Pit iron mine (32°.14’N X 83°.36’W) at an elevation of 314ft. This a purely terrestrial iron just 10.1 km (6.3 miles) west, southwest of the Pulaski County meteorite. The iron deposits contain Oligocene fossils, but these are secondary and they were formed by solution in Oligocene aged deposits. Limonite, an iron ore, also occurs as small but plentiful pebbles in Pulaski County and many pebbles contain enough iron to react to a magnet. Thus, searching for meteorites with a metal detector would be difficult.

However, all iron and most stone meteorites contain significant amounts of nickel. Terrestrial and manmade iron contain miniscule, nearly undetectable amounts of nickel. The Pulaski iron tests showed that it was kamacite, the typical nickel/iron alloy found in iron meteorites.

There is native, naturally occurring iron in Pulaski county at Jones Pit iron mine (32°.14’N X 83°.36’W) at an elevation of 314ft. This a purely terrestrial iron just 10.1 km (6.3 miles) west, southwest of the Pulaski County meteorite. The iron deposits contain Oligocene fossils, but these are secondary and they were formed by solution in Oligocene aged deposits. Limonite, an iron ore, also occurs as small but plentiful pebbles in Pulaski County and many pebbles contain enough iron to react to a magnet. Thus, searching for meteorites with a metal detector would be difficult.

However, all iron and most stone meteorites contain significant amounts of nickel. Terrestrial and manmade iron contain miniscule, nearly undetectable amounts of nickel. The Pulaski iron tests showed that it was kamacite, the typical nickel/iron alloy found in iron meteorites.

We are fortunate that the meteorite was found before it rusted away. The span of time raw iron can lay exposed on the surface before rusting away varies dramatically depending on its composition and the climate. As we well know, Georgia tends to be wet & humid. This was a small piece of iron. The 1966 report states that it was already partially altered. It probably couldn’t have survived on the surface, exposed in a pasture, for more than a few months. This suggests that it was either a recent fall or weathering had recently uncovered it.

Beginning at the beginning

In 2010 I wrote William Smith who, at the time, was Program Manager for the Regulatory Support Program of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. This was what remained of the Georgia Geological Survey. He replied as below:

05/Jan/2011

Dear Mr. Thurman:

Following the receipt of your letter inquiring about a Pulaski County Meteorite, I had our files checked. We have no files regarding the subject meteorite. I also distributed your letter to members of our staff who were long-term associates with the Georgia Geological Survey. None had knowledge of the Pulaski County Meteorite. Your letter included copies of information from the ‘Meteorites in Georgia’ publication, which is the only meteorite publication that we have.

William G. Smith

Clearly, this was a dead end.

Beginning at the beginning

In 2010 I wrote William Smith who, at the time, was Program Manager for the Regulatory Support Program of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. This was what remained of the Georgia Geological Survey. He replied as below:

05/Jan/2011

Dear Mr. Thurman:

Following the receipt of your letter inquiring about a Pulaski County Meteorite, I had our files checked. We have no files regarding the subject meteorite. I also distributed your letter to members of our staff who were long-term associates with the Georgia Geological Survey. None had knowledge of the Pulaski County Meteorite. Your letter included copies of information from the ‘Meteorites in Georgia’ publication, which is the only meteorite publication that we have.

William G. Smith

Clearly, this was a dead end.

Incorrect Listing

As of this October 2020 writing, the Meteorite Association of Georgia lists the Pulaski County find as synonymous with the Sardis iron (2), but this was shown to be incorrect by the original U.S. National Museum research in 1955.

As of this October 2020 writing, the Meteorite Association of Georgia lists the Pulaski County find as synonymous with the Sardis iron (2), but this was shown to be incorrect by the original U.S. National Museum research in 1955.

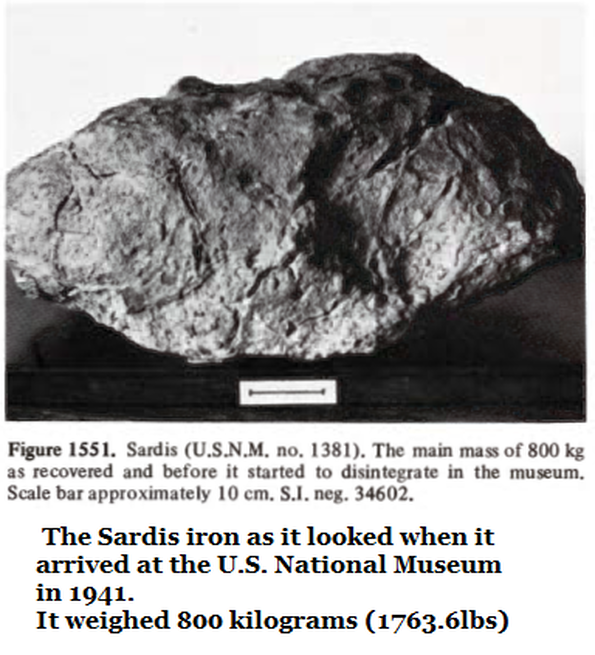

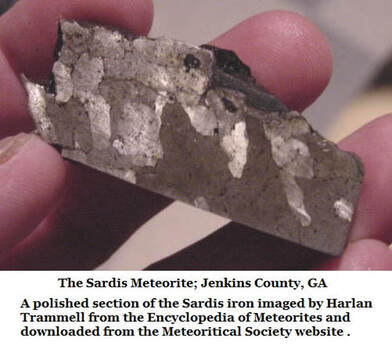

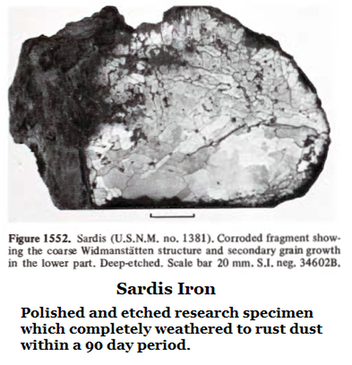

The Sardis Iron in Brief

The Sardis iron is likely one of the oldest meteorites ever found. This 1763lb iron was buried and unknown until a plow struck it in 1940. It was recovered in 1941 from Miocene aged sediments in Jenkins County, Georgia. The Miocene Epoch spans from 23 to 5 million years ago. By all appearances, this is when the Sardis fell.

The Sardis iron is likely one of the oldest meteorites ever found. This 1763lb iron was buried and unknown until a plow struck it in 1940. It was recovered in 1941 from Miocene aged sediments in Jenkins County, Georgia. The Miocene Epoch spans from 23 to 5 million years ago. By all appearances, this is when the Sardis fell.

When received by the U.S. National Museum the Sadris iron measured at 33” by 28” by 12” but it tended to disintegrate (rusts to dust) very quickly. To quote the 1966 report; “One apparently solid piece weighing about 5 pounds (2267grams) completely disintegrated in the museum in about 3 months time.” (1,pg.131) The theory of its preservation for millions of years is that it fell into the shallow sea which covered Georgia at that time and was quickly buried under sediments. It was buried in an oxygen deficient environment so it couldn’t rust away. (1,pg.113) It started rusting as soon as it was recovered, in the end researchers preserved samples by sealing them in plastic. There is a polished slice preserved in Lucite at the Georgia Capitol Museum.

If we accept that the Sardis is old, and that it disintegrates quickly it, seems unlikely that the 4oz (116 gram) specimen would endure long in a pasture. However, there’s additional proof that the two are different.

Separate from the Sardis Iron

The Pulaski County meteorite was described as a coarse octahedrite with a few small cohenite inclusions, possessing an average bandwidth of 1.3mm. (1,pg.129) The Sardis iron is also a coarse octahedrite but it contains no cohenite. The Sardis iron kamacite lamellae bandwidth is 2.5mm (5, pg1084).

To quote Henderson & Furcron; “The kamacite bands in the Pulaski County and the Sardis are different so we consider these two meteorites as different.” (1,pg129-130)

The Pulaski County meteorite was described as a coarse octahedrite with a few small cohenite inclusions, possessing an average bandwidth of 1.3mm. (1,pg.129) The Sardis iron is also a coarse octahedrite but it contains no cohenite. The Sardis iron kamacite lamellae bandwidth is 2.5mm (5, pg1084).

To quote Henderson & Furcron; “The kamacite bands in the Pulaski County and the Sardis are different so we consider these two meteorites as different.” (1,pg129-130)

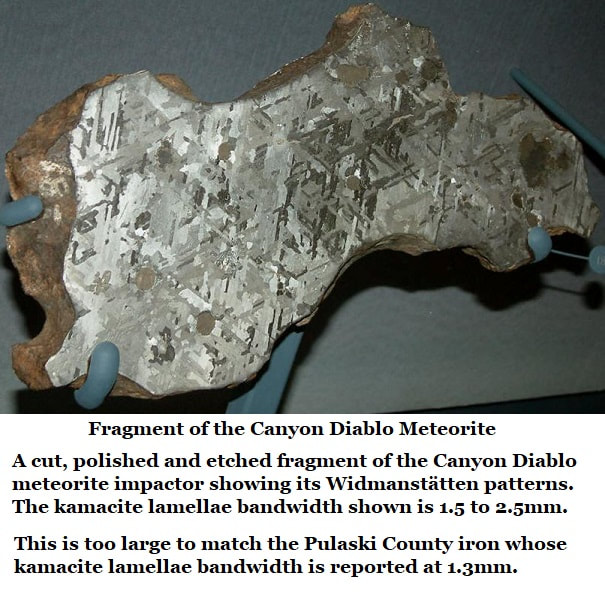

Other Unlikely Synonyms

The Meteoritical Society’s website (4) ranks the Pulaski iron as synonymous with Canyon Diablo iron meteorite and the Little Piney meteorite. The Little Piney is a chondrite or stony meteorite. This must be a cataloging error, the Pulaski literature firmly establishes that it is an iron, not a stony meteorite.

The Canyon Diablo is doubtless another cataloging error.

The Meteoritical Society’s website (4) ranks the Pulaski iron as synonymous with Canyon Diablo iron meteorite and the Little Piney meteorite. The Little Piney is a chondrite or stony meteorite. This must be a cataloging error, the Pulaski literature firmly establishes that it is an iron, not a stony meteorite.

The Canyon Diablo is doubtless another cataloging error.

Why Isn’t the Pulaski Iron Officially Recognized?

The U.S. National Museum is now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Back in 2010 I emailed them about their work with the Pulaski County meteorite; Ms. Linda Welzenbach graciously replied to a couple of my inquiries.

01/December/2010

“Pulaski County is synonymous with two meteorites, one is the Canyon Diablo and the other is Little Piney, the latter of which is an 1893 ordinary chondrite (stony) fall from Missouri. That pretty much leaves your sample as Canyon Diablo. I will ask Roy Clarke our emeritus curator if he knows anything about this.”

The U.S. National Museum is now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Back in 2010 I emailed them about their work with the Pulaski County meteorite; Ms. Linda Welzenbach graciously replied to a couple of my inquiries.

01/December/2010

“Pulaski County is synonymous with two meteorites, one is the Canyon Diablo and the other is Little Piney, the latter of which is an 1893 ordinary chondrite (stony) fall from Missouri. That pretty much leaves your sample as Canyon Diablo. I will ask Roy Clarke our emeritus curator if he knows anything about this.”

20/December/2010

“Sorry it’s taken me so long to get back to you. I spoke at length with Roy Clarke and here’s what we were able to settle on. Ed Henderson and A.S. Furcron had worked together on meteorites and tektites from Georgia over a number of years during the 1950’s and ‘60s. The specimen was confirmed as a small iron meteorite and returned to the finder without having been described in the meteoritic literature. Work (at the Smithsonian) was not carried to the point of establishing the specimen as a newly found meteorite that fell in Georgia. Therefore an official name was never established. The later renaming didn’t involve us, so I can’t comment on how that happened, and without the meteorite itself, this mystery will likely never be solved.”

“Sorry it’s taken me so long to get back to you. I spoke at length with Roy Clarke and here’s what we were able to settle on. Ed Henderson and A.S. Furcron had worked together on meteorites and tektites from Georgia over a number of years during the 1950’s and ‘60s. The specimen was confirmed as a small iron meteorite and returned to the finder without having been described in the meteoritic literature. Work (at the Smithsonian) was not carried to the point of establishing the specimen as a newly found meteorite that fell in Georgia. Therefore an official name was never established. The later renaming didn’t involve us, so I can’t comment on how that happened, and without the meteorite itself, this mystery will likely never be solved.”

Arizona’s Canyon Diablo meteorite is well known from many, usually small, fragments. It's the meteorite which created Arizona’s famous Meteorite Crater about 50,000 years ago. In the meteor’s flight across the USA it scattered many fragments. More occur in the area surrounding the crater. However, they can all be traced back to the main mass by their kamacite lamellae bandwidth of 1.5-2.5mm. (4, Canyon Diablo entry) That bandwidth disqualifies the Pulaski iron as being yet another fragment of the Canyon Diablo.

Canyon Diablo Kamacite Lamellae Bandwidth, 1.5-2.5mm

Pulaski iron Kamacite Lamellae Bandwidth, 1.3mm

Canyon Diablo Kamacite Lamellae Bandwidth, 1.5-2.5mm

Pulaski iron Kamacite Lamellae Bandwidth, 1.3mm

It would seem, from what evidence is available and pending new evidence that the Pulaski County iron is a stand-alone meteorite unrelated to other finds. That one description of it as a fragment suggests that other specimens might exist however, have they weathered into dust?

Pulaski County Conclusion

In 1955 John Peterson showed the Georgia Geologic Survey a meteorite, and the survey confirmed that identification by sending the sample to the U.S. National Museum, it was then returned to the Georgia Geologic Survey and on to John Peterson.

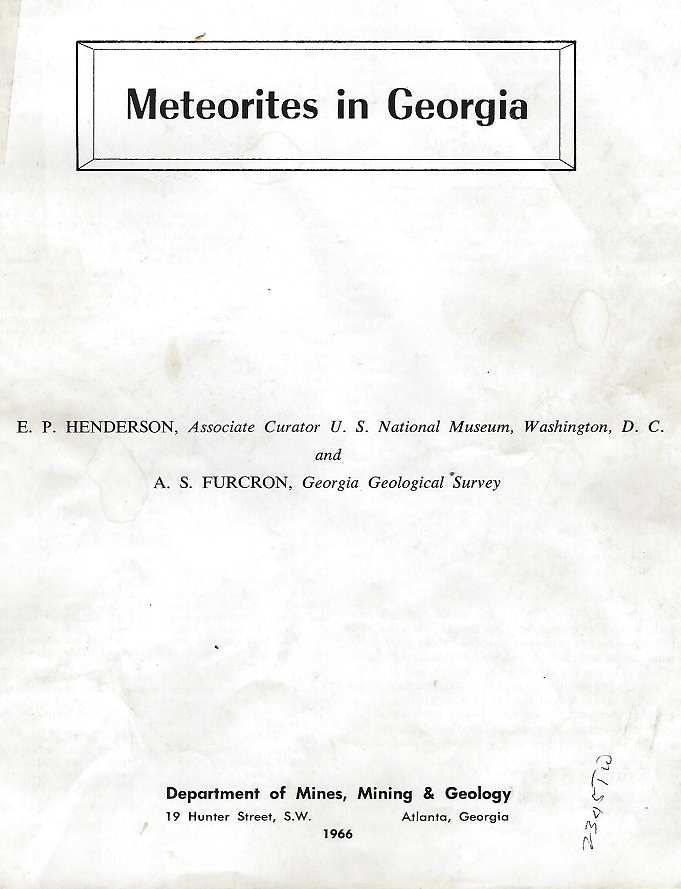

E.P. Henderson of the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C. and A.S. Furcron of the Georgia Geologic Survey are both considered experts on meteorites & tektites. They collaborated on the report entitled Meteorites in Georgia which was published in 1966 by the Georgia Geologic Survey in Atlanta.

In 1955 John Peterson showed the Georgia Geologic Survey a meteorite, and the survey confirmed that identification by sending the sample to the U.S. National Museum, it was then returned to the Georgia Geologic Survey and on to John Peterson.

E.P. Henderson of the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C. and A.S. Furcron of the Georgia Geologic Survey are both considered experts on meteorites & tektites. They collaborated on the report entitled Meteorites in Georgia which was published in 1966 by the Georgia Geologic Survey in Atlanta.

Furcron had apparently held the Pulaski County iron in his hand & sent it to the National Museum. The National Museum compared it to the Sardis Iron in their collection, so no doubt Henderson, as the museum’s meteorite expert, also handled the Pulaski County iron.

Yet, the Pulaski County iron not only failed to get included on the national list of meteorites, it somehow, over the years, got associated with a stony meteorite and two distinct irons. Clearly the Pulaski is a separate specimen. The literature clearly shows the Pulaski matches none of the meteorites it has been associated with.

Sometimes science goes awry. It would seem to the author, that the existing literature has enough research and information to support establishing the Pulaski County iron as independent fall. The chances of reviewing the original 116 gram sample seem very slim. I wonder if Mr. John Peterson, or one of his heirs, is still in the Hapeville area and still has the specimen? I wonder if it even still exists.

Yet, the Pulaski County iron not only failed to get included on the national list of meteorites, it somehow, over the years, got associated with a stony meteorite and two distinct irons. Clearly the Pulaski is a separate specimen. The literature clearly shows the Pulaski matches none of the meteorites it has been associated with.

Sometimes science goes awry. It would seem to the author, that the existing literature has enough research and information to support establishing the Pulaski County iron as independent fall. The chances of reviewing the original 116 gram sample seem very slim. I wonder if Mr. John Peterson, or one of his heirs, is still in the Hapeville area and still has the specimen? I wonder if it even still exists.

Thanks to Ryan Roney at Tellus Science Museum for advising me on the oxidation of iron meteorites exposed to the elements.

Note:

On Tuesday, 22/Aug/2023, Dennis Worthington commented on this article being posted on Facebook's Georgia Fossils Group, that John Peterson appeared on the 1950 census. Dennis reported that according to the census Peterson was "...Born Louisiana, had a wife named Helen (Florida), and a son named E. Dala. He worked at the Department of Agriculture, which would possibly be the connection with a pasture in Pulaski county."

Thanks Dennis for the assist!

On Tuesday, 22/Aug/2023, Dennis Worthington commented on this article being posted on Facebook's Georgia Fossils Group, that John Peterson appeared on the 1950 census. Dennis reported that according to the census Peterson was "...Born Louisiana, had a wife named Helen (Florida), and a son named E. Dala. He worked at the Department of Agriculture, which would possibly be the connection with a pasture in Pulaski county."

Thanks Dennis for the assist!

References:

- Henderson, E.P.; Furcron A.S.; Meteorites in Georgia, Georgia Dept of Mines, Mining & Geology, Atlanta, 1966.

- Meteorite Association of Georgia; meteoriteassociationofgeorgia.org/default.htm

- Cook, Robert B.; Minerals of Georgia, Their Properties and Occurrences, Georgia Geological Survey, Bulletin 92, 1978

- The Meteoritical Society; www.lpi.usra.edu/meteor/metbull.php

- Buchwald, Vagn F.; Sardis, Georgia, USA, Handbook of Iron Meteorites, University of California Press, Pg.1084, 1975

- Personal communications; Ms. Linda Welzenbach, Smithsonian NMNH, December 2010