14J: Georgiaites,

Tektites from Georgia.

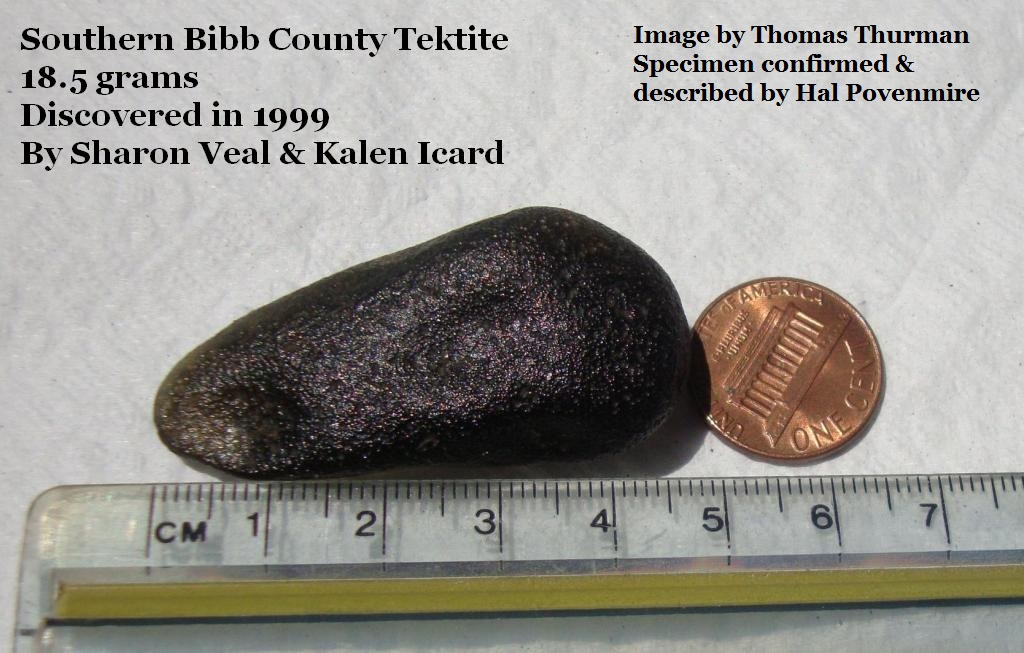

By Thomas Thurman

Perhaps Georgia's most collected & valuable specimens.

Tektites from Georgia.

By Thomas Thurman

Perhaps Georgia's most collected & valuable specimens.

So what's a tektite?

A tektite is glassy debris from an extraterrestrial impact; the impactor can be a meteorite or comet.

Imagine throwing a rock into a mud puddle and observing the pattern of splash droplets.

Now imagine a large meteorite impacting a shallow, coastal sea; the “splash” throws molten material on a trajectory into space, then it falls again to Earth, transformed, usually as dark colored glassy material typically black or green in color. These are tektites. There are many varieties.

A tektite is glassy debris from an extraterrestrial impact; the impactor can be a meteorite or comet.

Imagine throwing a rock into a mud puddle and observing the pattern of splash droplets.

Now imagine a large meteorite impacting a shallow, coastal sea; the “splash” throws molten material on a trajectory into space, then it falls again to Earth, transformed, usually as dark colored glassy material typically black or green in color. These are tektites. There are many varieties.

The geographic areas they are found in are called strewn fields. If you have a spread of matching tektites found in their original locations, from a wide enough geographic area, you can triangulate their source.

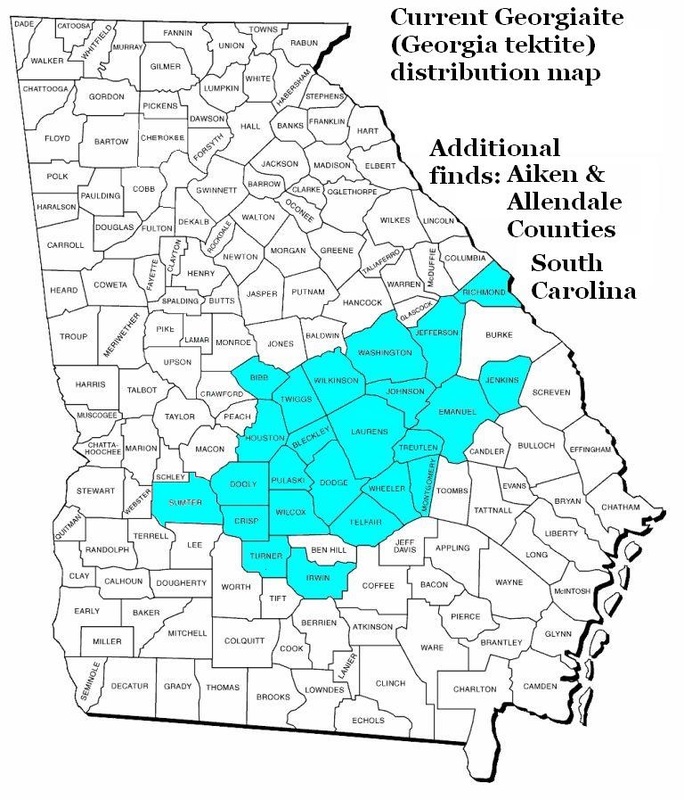

A tektite found in Georgia is called a georgiaite, it's believed that georgiaites originated from the Chesapeake Bay impact event about 35.5 million years ago.

A tektite found in Georgia is called a georgiaite, it's believed that georgiaites originated from the Chesapeake Bay impact event about 35.5 million years ago.

Sadly, no georgiaite has ever been found in its original location. According to Hal Povenmire, who’s recovered and handled more georgiaites than anyone, there are approximately 1,000 to 1,500 known specimens. Povenmire has written both articles and books on the subject. He's even seen a georgiaite or two that Native Americans had worked into points.

None of these specimens have come from age appropriate sediments.

None of these specimens have come from age appropriate sediments.

Hal Povenmire passed in early

December 2019.

The tektite world will never be the same.

December 2019.

The tektite world will never be the same.

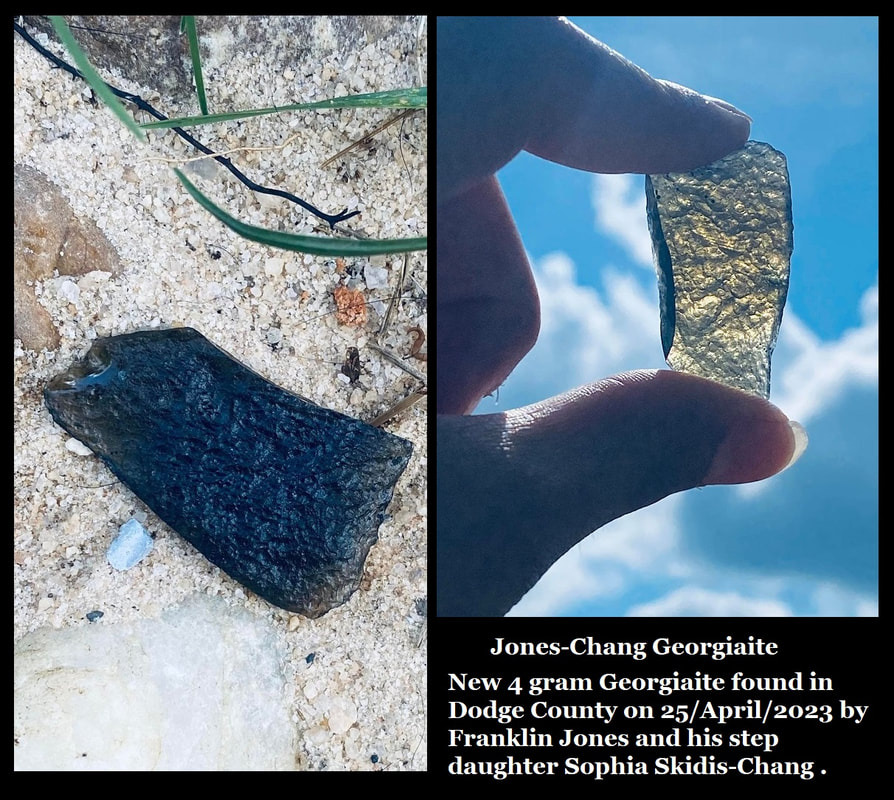

New Finds

For years many thought that Georgia's strewn fields were played out, that there were probably no new finds to make.

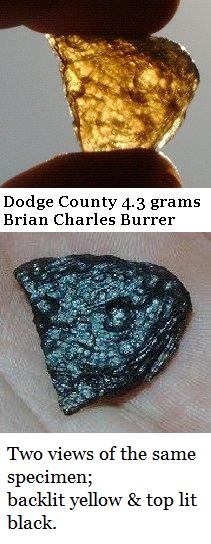

This is not true; just in 2017, two new georgiaites were found and made available in the markets. One from Dodge County found by Travis Darden and one from Bleckley County found by Jamie Berryhill. Both were found by amateurs.

On 8/Sept/2018 Michelle Williams of Cochran, Georgia reported a 24.74 gram beauty found in Bleckley County

It has been the pleasure of this website to introduce these new finds and advise the owners of how to bring them to the markets.

For years many thought that Georgia's strewn fields were played out, that there were probably no new finds to make.

This is not true; just in 2017, two new georgiaites were found and made available in the markets. One from Dodge County found by Travis Darden and one from Bleckley County found by Jamie Berryhill. Both were found by amateurs.

On 8/Sept/2018 Michelle Williams of Cochran, Georgia reported a 24.74 gram beauty found in Bleckley County

It has been the pleasure of this website to introduce these new finds and advise the owners of how to bring them to the markets.

Another New Find

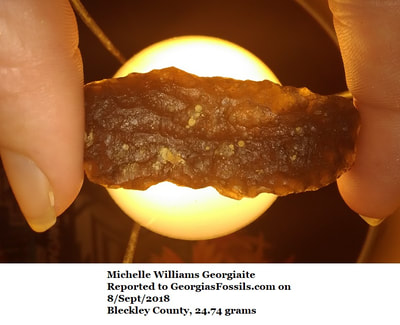

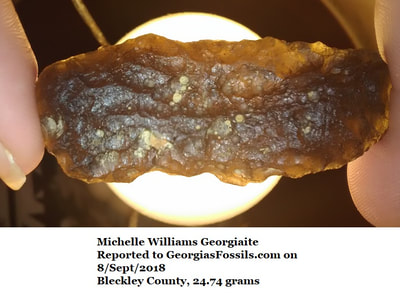

The Michelle Williams Georgiaite

On 8/Sept/2018 Michelle Williams of Cochran, Georgia reported a 24.74 gram beauty found in Bleckley County

It has been the pleasure of this website to introduce these new finds and advise the owners of how to bring them to the markets.

The Michelle Williams Georgiaite

On 8/Sept/2018 Michelle Williams of Cochran, Georgia reported a 24.74 gram beauty found in Bleckley County

It has been the pleasure of this website to introduce these new finds and advise the owners of how to bring them to the markets.

Physical Description

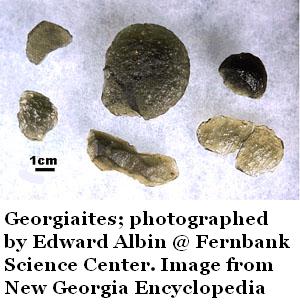

Georgiaites are distinct tektites; known only from the Southeastern USA. The vast majority of these are from the central and eastern portion of Georgia’s Coastal Plain, a handful have been confirmed from South Carolina.

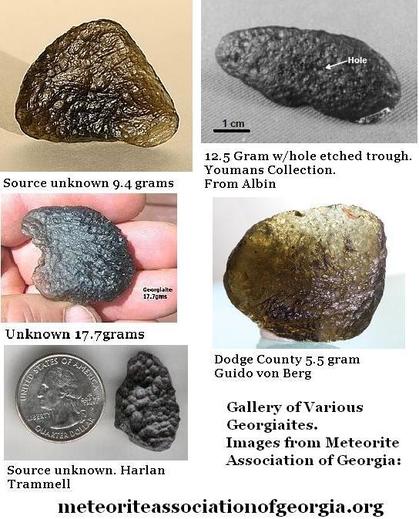

Complete georgiaite specimens are typically shaped like an elongated teardrop, an aerodynamic shape, though there are many exceptions to this. They are almost always rounded.

They have passed through the space and the atmosphere as molten material. They were then completely cooled and soon buried in the sediments which the Chesapeake Bay impact stirred up. Those striking north of the Fall Line, north of the coastline, probably shattered on impact with the ground.

They are dense and glassy. Generally black in color, but translucent, back-lighting will make it appear greenish or yellowish. Their surfaces are typically dimpled.

Physical Description

Georgiaites are distinct tektites; known only from the Southeastern USA. The vast majority of these are from the central and eastern portion of Georgia’s Coastal Plain, a handful have been confirmed from South Carolina.

Complete georgiaite specimens are typically shaped like an elongated teardrop, an aerodynamic shape, though there are many exceptions to this. They are almost always rounded.

They have passed through the space and the atmosphere as molten material. They were then completely cooled and soon buried in the sediments which the Chesapeake Bay impact stirred up. Those striking north of the Fall Line, north of the coastline, probably shattered on impact with the ground.

They are dense and glassy. Generally black in color, but translucent, back-lighting will make it appear greenish or yellowish. Their surfaces are typically dimpled.

Valued by Collectors

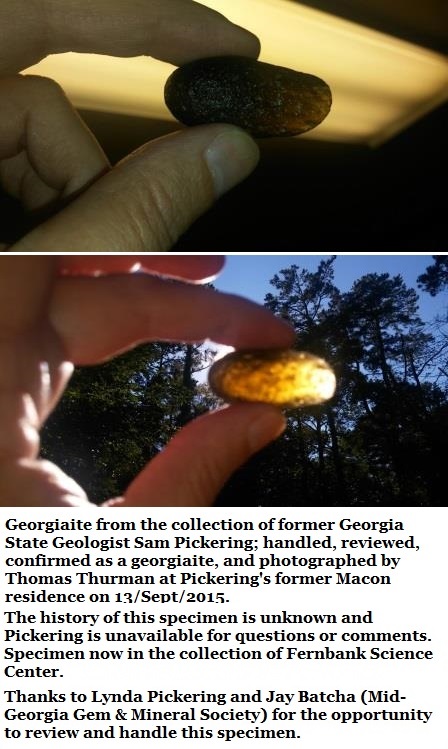

Georgiaites are rare and valuable, especially in Europe were collectors might pay hundreds of dollars per gram (retail) for the best specimens. The average size is 10-12 grams. The largest known georgiaite is 86.4 grams (3.05 ounces) and is in the Fernbank collection. Large ones are very likely still out there.

Very few new specimens come to the markets as very few Georgians are actually looking for georgiaites.

If you think you’ve found a georgiaite then it needs to be confirmed; contact Thomas for instructions on sending some pics. [email protected]

Georgiaites are rare and valuable, especially in Europe were collectors might pay hundreds of dollars per gram (retail) for the best specimens. The average size is 10-12 grams. The largest known georgiaite is 86.4 grams (3.05 ounces) and is in the Fernbank collection. Large ones are very likely still out there.

Very few new specimens come to the markets as very few Georgians are actually looking for georgiaites.

If you think you’ve found a georgiaite then it needs to be confirmed; contact Thomas for instructions on sending some pics. [email protected]

The Event

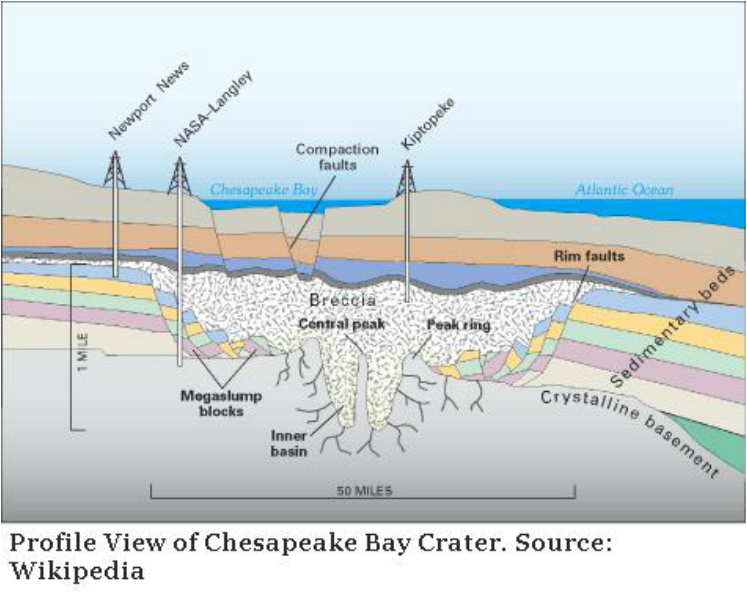

About 35.5 million years ago a bolide crashed into coastal Maryland & Virginia forming Chesapeake Bay; 500 miles northeast of Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

Bolide is the term scientist use for an extraterrestrial impactor when they don’t know if it was a rocky meteorite or an icy comet.

This was a catastrophic event locally; devastating event for most of the eastern seaboard of the USA. Furthermore, it was not the only large impact event from this timeframe. The two largest identifiable craters are the Popigai structure (100 km or 62.14 miles across) in Siberia and the Chesapeake Bay impact crater (85 km or 52.82 miles across).

Some researchers have speculated that the Chesapeake Bay and other Late Eocene impacts triggered the global cooling which led to the global Eocene/Oligocene horizon extinction event which occurred about a million years later. Additionally, it’s been proposed that these impacts influenced global climates and perhaps “tipped the scales” towards the Eocene Epoch glacial extinction event.

In a 2001 article by Hillary Mayell with the National Geographic News; United States Geological Survey researchers David Powars and C. Wylie Poag argued that a 2 million yearlong bolide shower occurred between 36 and 34 million years ago; including the Chesapeake Bay impact event.

To quote Poag’s argument from this 2001 National Geographic article:

Global paleo-temperatures during the early Eocene show the world was getting cooler. Around 35 million years ago, at the end of the Eocene, there was a warm pulse, and for a short period of time the Earth warmed. Then beginning at around 34 million years ago the Earth cooled very rapidly. At 33.4 million years ago there was a major extinction event.

But did these impacts influence the extinction event?

We’ve looked briefly at the global sea level work of Dr. Kenneth Miller with Rutgers; Dr. Miller has also looked into the Eocene/Oligocene horizon question and reviewed the evidence for an impact related extinction event.

Bear in mind, the Eocene/Oligocene horizon stands at 33.9 million years ago. Both Popigai and the Chesapeake Bay impact are significantly older, they're dated with a fair degree of confidence to about 35-plus million years old. The Chesapeake Bay impact event is dated to 35.5 million years ago with a possible error rate of 300,000 years. There is no meaningful disagreement on these dates.

This gives us a 1-plus million year gap between the impacts events, the extinction event and the global cooling which marks the Eocene/Oligocene boundary; one million years is a long stretch of time.

In 2007 the Geological Society of America published a paper by Kenneth Miller entitled “Eocene-Oligocene Global Climate and Sea Level Changes: St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama.” Miller’s team concluded that the dramatic fall in sea levels (55 meters or 180 feet) marking the Eocene/Oligocene boundary was an ice driven extinction event; a natural fall in sea levels requiring no extraterrestrial (meteorite impact) influences.

In a separate 2009 paper led by Aimee Pusz, Kenneth Miller, and James D. Wright entitled: “Stable Isotopic Response to Late Eocene Extraterrestrial Impacts” researchers looked specifically at the oxygen isotope levels in sediments immediately before and after these impacts. They could find no global temperature changes directly associated with the Popigai or Chesapeake Bay impact events.

Still; the event was catastrophic for the Eastern Seaboard of North America.

The impact blasted its crater. Millions of tons of water evaporated and the vast Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater was instantly excavated. The detonation of the impact would have cast sea floor material high into the air at terrific velocities. The shock wave that was generated sent a wall of water, a tsunami, racing across the north Atlantic.

There is evidence suggesting that this tidal wave topped the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Moments later; sea water rushed back into the still hot crater to fill the void. This would have affected the whole East Coast probably even pulling water from the sea which covered Georgia.

Perhaps at this point georgiaites fell. They were forever altered by the heat of the impact, flight through the atmosphere, into space, re-entry into the atmosphere and then falling onto Georgia’s Coastal Plain is a still partially molten form to be cooled in the shallow Southeastern Sea.

Next came the rebound as the crater refilled with water, this would have sent a second tidal wave racing out from the new Chesapeake Bay, this tidal wave certainly devastated Georgia’s Fall Line coastline.

About 35.5 million years ago a bolide crashed into coastal Maryland & Virginia forming Chesapeake Bay; 500 miles northeast of Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

Bolide is the term scientist use for an extraterrestrial impactor when they don’t know if it was a rocky meteorite or an icy comet.

This was a catastrophic event locally; devastating event for most of the eastern seaboard of the USA. Furthermore, it was not the only large impact event from this timeframe. The two largest identifiable craters are the Popigai structure (100 km or 62.14 miles across) in Siberia and the Chesapeake Bay impact crater (85 km or 52.82 miles across).

Some researchers have speculated that the Chesapeake Bay and other Late Eocene impacts triggered the global cooling which led to the global Eocene/Oligocene horizon extinction event which occurred about a million years later. Additionally, it’s been proposed that these impacts influenced global climates and perhaps “tipped the scales” towards the Eocene Epoch glacial extinction event.

In a 2001 article by Hillary Mayell with the National Geographic News; United States Geological Survey researchers David Powars and C. Wylie Poag argued that a 2 million yearlong bolide shower occurred between 36 and 34 million years ago; including the Chesapeake Bay impact event.

To quote Poag’s argument from this 2001 National Geographic article:

Global paleo-temperatures during the early Eocene show the world was getting cooler. Around 35 million years ago, at the end of the Eocene, there was a warm pulse, and for a short period of time the Earth warmed. Then beginning at around 34 million years ago the Earth cooled very rapidly. At 33.4 million years ago there was a major extinction event.

But did these impacts influence the extinction event?

We’ve looked briefly at the global sea level work of Dr. Kenneth Miller with Rutgers; Dr. Miller has also looked into the Eocene/Oligocene horizon question and reviewed the evidence for an impact related extinction event.

Bear in mind, the Eocene/Oligocene horizon stands at 33.9 million years ago. Both Popigai and the Chesapeake Bay impact are significantly older, they're dated with a fair degree of confidence to about 35-plus million years old. The Chesapeake Bay impact event is dated to 35.5 million years ago with a possible error rate of 300,000 years. There is no meaningful disagreement on these dates.

This gives us a 1-plus million year gap between the impacts events, the extinction event and the global cooling which marks the Eocene/Oligocene boundary; one million years is a long stretch of time.

In 2007 the Geological Society of America published a paper by Kenneth Miller entitled “Eocene-Oligocene Global Climate and Sea Level Changes: St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama.” Miller’s team concluded that the dramatic fall in sea levels (55 meters or 180 feet) marking the Eocene/Oligocene boundary was an ice driven extinction event; a natural fall in sea levels requiring no extraterrestrial (meteorite impact) influences.

In a separate 2009 paper led by Aimee Pusz, Kenneth Miller, and James D. Wright entitled: “Stable Isotopic Response to Late Eocene Extraterrestrial Impacts” researchers looked specifically at the oxygen isotope levels in sediments immediately before and after these impacts. They could find no global temperature changes directly associated with the Popigai or Chesapeake Bay impact events.

Still; the event was catastrophic for the Eastern Seaboard of North America.

The impact blasted its crater. Millions of tons of water evaporated and the vast Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater was instantly excavated. The detonation of the impact would have cast sea floor material high into the air at terrific velocities. The shock wave that was generated sent a wall of water, a tsunami, racing across the north Atlantic.

There is evidence suggesting that this tidal wave topped the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Moments later; sea water rushed back into the still hot crater to fill the void. This would have affected the whole East Coast probably even pulling water from the sea which covered Georgia.

Perhaps at this point georgiaites fell. They were forever altered by the heat of the impact, flight through the atmosphere, into space, re-entry into the atmosphere and then falling onto Georgia’s Coastal Plain is a still partially molten form to be cooled in the shallow Southeastern Sea.

Next came the rebound as the crater refilled with water, this would have sent a second tidal wave racing out from the new Chesapeake Bay, this tidal wave certainly devastated Georgia’s Fall Line coastline.

Connecting Georgiaites to Chesapeake Bay

The Meteorite Association of Georgia maintains a wonderful Georgia tektite image gallery online (meteoriteassociationofgeorgia.org); they report that the first georgiaite was documented in 1938 by E.P. Henderson of the Smithsonian. It was found by Dewey Horne near the town Empire, Georgia in Bleckley County.

For years… debates raged about the source for Georgia’s tektites, many argued that they were debris from meteorite impacts or volcanic activity on the moon. But if that were true, why are the ones from Georgia so distinct?

The Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater was discovered in 1983.

The Meteorite Association of Georgia maintains a wonderful Georgia tektite image gallery online (meteoriteassociationofgeorgia.org); they report that the first georgiaite was documented in 1938 by E.P. Henderson of the Smithsonian. It was found by Dewey Horne near the town Empire, Georgia in Bleckley County.

For years… debates raged about the source for Georgia’s tektites, many argued that they were debris from meteorite impacts or volcanic activity on the moon. But if that were true, why are the ones from Georgia so distinct?

The Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater was discovered in 1983.

In a 1996 research paper by Dr. Edward Albin at Fernbank Science Center in Atlanta, ten georgiaites from the Howard collection at the Fernbank Museum of Natural History were dated using the potassium-argon method.

These produced an average age of 34.7 million years with a possible error rate of 400,000 years either plus or minus.

This figure matches the age of the Chesapeake Bay impact Crater. Yet, this isn’t conclusive evidence that georgiaites originated with the Chesapeake Bay impact event.

One of the problems is that no Georgia tektite has ever been recovered from age appropriate sediments, they’re typically found in the significantly younger Altamaha Formation dated to the Miocene Epoch (23.0 to 5.3 million years old).

The older tektites occur as naturally relocated material transported downrange from older sediments by water erosion. Georgiaites typically occur as clusters in channel lag fill structures of the Altamaha, among rounded quartz gravel.

Since the known georgiaites occur as secondary deposits, relocated from their original position; Ed Albin at Fernbank has questioned whether the tern “Strewn Field” should apply to georgiaites. It is assumed that they haven’t travelled far, but we don’t know how far.

All Georgia tektites are valuable, but the most valuable of all will be the first one which can be conclusively shown to come from age appropriate sediments. Such sediments are common enough in the Southeast.

However, when I asked Paul Huddlestun about this, the man who has done more field research on Georgia’s Coastal plain than anyone, he expressed serious doubts as to whether any Georgia tektite would ever be found in Late Eocene sediments.

As channel lag they’re concentrated in the younger Altamaha Formation. They would be much more dispersed in the Eocene sediments, and very possibly destroyed by natural processes.

If you think you’ve found a georgiaite then it needs to be confirmed; contact Thomas for instructions on sending some pics. [email protected]

These produced an average age of 34.7 million years with a possible error rate of 400,000 years either plus or minus.

This figure matches the age of the Chesapeake Bay impact Crater. Yet, this isn’t conclusive evidence that georgiaites originated with the Chesapeake Bay impact event.

One of the problems is that no Georgia tektite has ever been recovered from age appropriate sediments, they’re typically found in the significantly younger Altamaha Formation dated to the Miocene Epoch (23.0 to 5.3 million years old).

The older tektites occur as naturally relocated material transported downrange from older sediments by water erosion. Georgiaites typically occur as clusters in channel lag fill structures of the Altamaha, among rounded quartz gravel.

Since the known georgiaites occur as secondary deposits, relocated from their original position; Ed Albin at Fernbank has questioned whether the tern “Strewn Field” should apply to georgiaites. It is assumed that they haven’t travelled far, but we don’t know how far.

All Georgia tektites are valuable, but the most valuable of all will be the first one which can be conclusively shown to come from age appropriate sediments. Such sediments are common enough in the Southeast.

However, when I asked Paul Huddlestun about this, the man who has done more field research on Georgia’s Coastal plain than anyone, he expressed serious doubts as to whether any Georgia tektite would ever be found in Late Eocene sediments.

As channel lag they’re concentrated in the younger Altamaha Formation. They would be much more dispersed in the Eocene sediments, and very possibly destroyed by natural processes.

If you think you’ve found a georgiaite then it needs to be confirmed; contact Thomas for instructions on sending some pics. [email protected]

References:

Oligocene stratigraphy;

The Oligocene; A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia. Paul F. Huddlestun. Bulletin 105, Georgia Geologic Survey, Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division. 1993

Eocene Impacts

Upper Eocene Impact Stratigraphy of the Georgia Coastal Plain; R. Scott Harris, Department of Geosciences, Georgia State University. Georgia Geological Society Guidebook, Volume 29, pgs 25-34, 2009

Chesapeake Bay Crater Offers Clues to Ancient Cataclysm; by Hillary Mayell, National Geographic News; 13/Nov/2001

• news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/11/1113_chesapeakcrater.html

• Interviews over the Chesapeake Bay Impact with USGS researchers; David Powars & C.

Wylie Poag during annual meeting of the Geological Society of America

Dating Georgia’s tektites

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

The First Documented Georgia-Area tektite Found in Bibb County, Georgia. Hal Povenmire, Indian Harbor Beach, Florida. Summer 2011

Oxygen Isotope levels & the Eocene/Oligocene Boundary

• Eocene-Oligocene global climate and sea level changes: St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama. Kenneth G. Miller, James V. Browning, Marie-Pierre Aubry, Bridget S. Wade, Miriam E. Katz, Andrew A. Kulpecz & James D. Wright. Geological Society of America Bulletin, January/February 2008.

• Stable Isotopic Response to Late Eocene Extraterrestrial Impacts. Aimee E. Pusz, Kenneth G. Miller, James D. Wright, Miriam E. Katz, Benjamin S. Cramer, Dennis V. Kent. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 452, 2009

Oligocene stratigraphy;

The Oligocene; A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia. Paul F. Huddlestun. Bulletin 105, Georgia Geologic Survey, Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division. 1993

Eocene Impacts

Upper Eocene Impact Stratigraphy of the Georgia Coastal Plain; R. Scott Harris, Department of Geosciences, Georgia State University. Georgia Geological Society Guidebook, Volume 29, pgs 25-34, 2009

Chesapeake Bay Crater Offers Clues to Ancient Cataclysm; by Hillary Mayell, National Geographic News; 13/Nov/2001

• news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/11/1113_chesapeakcrater.html

• Interviews over the Chesapeake Bay Impact with USGS researchers; David Powars & C.

Wylie Poag during annual meeting of the Geological Society of America

Dating Georgia’s tektites

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

The First Documented Georgia-Area tektite Found in Bibb County, Georgia. Hal Povenmire, Indian Harbor Beach, Florida. Summer 2011

Oxygen Isotope levels & the Eocene/Oligocene Boundary

• Eocene-Oligocene global climate and sea level changes: St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama. Kenneth G. Miller, James V. Browning, Marie-Pierre Aubry, Bridget S. Wade, Miriam E. Katz, Andrew A. Kulpecz & James D. Wright. Geological Society of America Bulletin, January/February 2008.

• Stable Isotopic Response to Late Eocene Extraterrestrial Impacts. Aimee E. Pusz, Kenneth G. Miller, James D. Wright, Miriam E. Katz, Benjamin S. Cramer, Dennis V. Kent. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 452, 2009