14M:

Eocene Terrestrial Mammals

From

Gordon; Georgia

A review by

Thomas Thurman

Posted 08/December/2019

Paleontology is alive and well at Georgia College in Milledgeville. In 2019 Parker D. Rhinehart published a paper revealing 4 previously unreported terrestrial mammal species from Hardie Mine; Alfred J. Mead and Dennis Parmley stood as co-authors. (1)

Wilkinson County’s Hardie Mine is an inactive kaolin mine just north of Gordon, Georgia in Wilkinson County. It has been a treasure trove of Eocene Fossils and previous work from Georgia College has done a splendid job of collecting, researching and publishing these finds.

Wilkinson County’s Hardie Mine is an inactive kaolin mine just north of Gordon, Georgia in Wilkinson County. It has been a treasure trove of Eocene Fossils and previous work from Georgia College has done a splendid job of collecting, researching and publishing these finds.

The fossils come from a spoil pile of the Clinchfield Formation near the north wall of mine pit. At the wall the Clinchfield Formation occurs as a bed approximately 1 meter (3.28ft) thick underlain by kaolin deposits and overlain by non-fossiliferous Twiggs Clay.

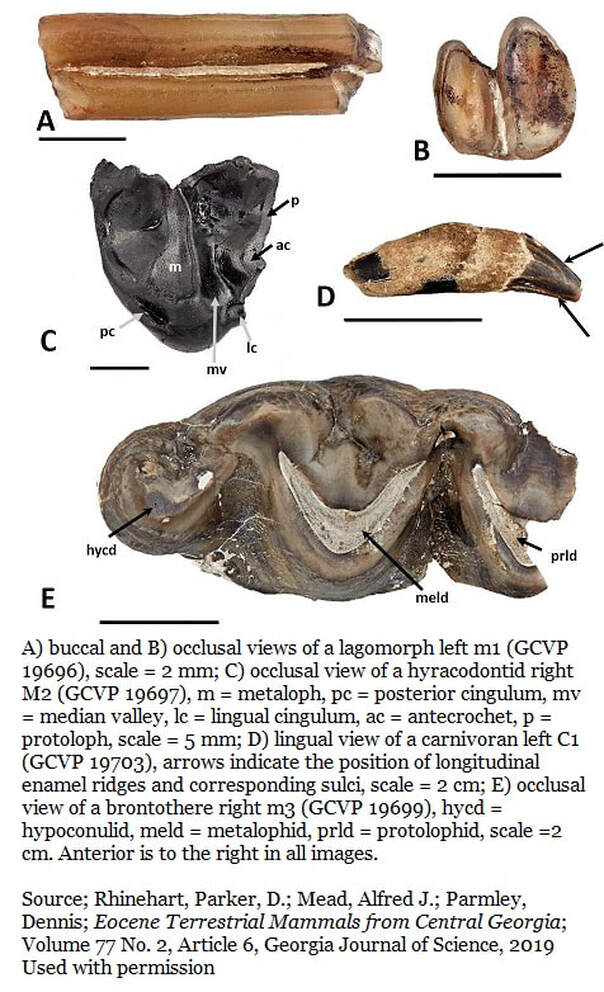

Rhinehart reports a Daphoenus (bear dog) species unknown, a Palaeolagus temnodon (rabbit), Megacerops (brontothere) species unknown, and Hyracodon (hornless rhino) species unknown.

You no doubt noticed they’re all teeth. Tooth enamel is the hardest substance the body creates and the one which is most easily preserved as fossils.

Rhinehart reports a Daphoenus (bear dog) species unknown, a Palaeolagus temnodon (rabbit), Megacerops (brontothere) species unknown, and Hyracodon (hornless rhino) species unknown.

You no doubt noticed they’re all teeth. Tooth enamel is the hardest substance the body creates and the one which is most easily preserved as fossils.

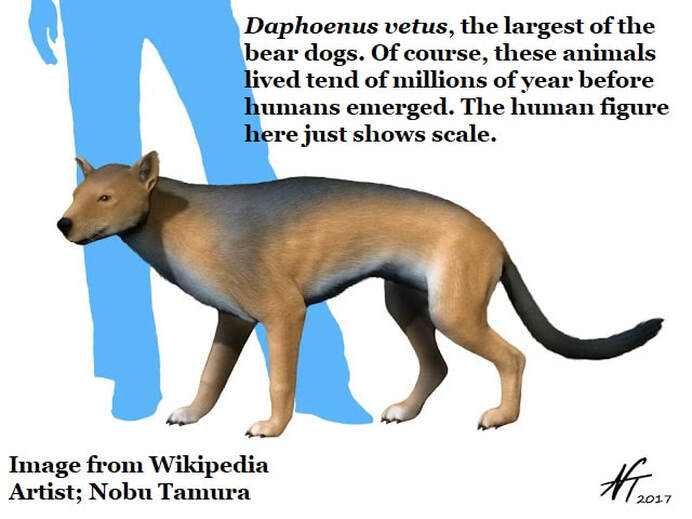

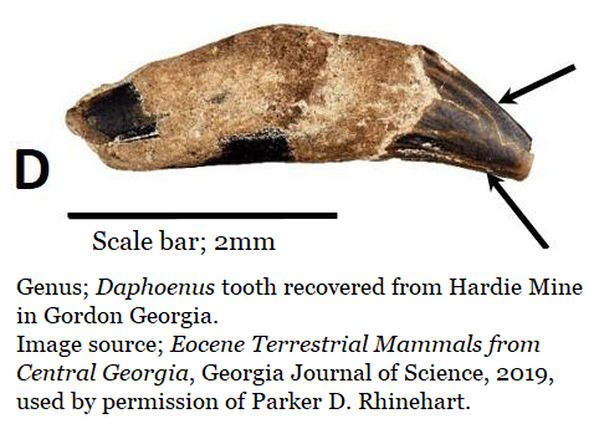

Daphoenus (bear dog)

The canine tooth shown was compared to Daphoenus and Hyaenodon mustelinus (Hyena-tooth) specimens from Badlands National Park and held in the Georgia College vertebrate paleontology collections. The size and dimensions of the tooth clearly identified it as a bear-dog.

The canine tooth shown was compared to Daphoenus and Hyaenodon mustelinus (Hyena-tooth) specimens from Badlands National Park and held in the Georgia College vertebrate paleontology collections. The size and dimensions of the tooth clearly identified it as a bear-dog.

Daphoenus from Wikipedia:

“Daphoenus, like the rest of its family, was called a "bear dog" because it had characteristics of both bears and dogs. These animals were about the size of the present-day coyote. Daphoenus vetus was the largest species. The male skulls could reach up to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) in length. Daphoenus had short legs and could only make quick sprints; it was not capable of running long distances. It is thought that these animals ambushed their prey and did some scavenging. Fossil footprints suggested that, like present-day bears, these animals walked in a flat-footed way. Daphoenus dug burrows for their offspring to stay in and hide from their prey.”

To quote Rhinehart’s paper;

“The Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Daphoenus in the southeastern United States.”

“Daphoenus, like the rest of its family, was called a "bear dog" because it had characteristics of both bears and dogs. These animals were about the size of the present-day coyote. Daphoenus vetus was the largest species. The male skulls could reach up to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) in length. Daphoenus had short legs and could only make quick sprints; it was not capable of running long distances. It is thought that these animals ambushed their prey and did some scavenging. Fossil footprints suggested that, like present-day bears, these animals walked in a flat-footed way. Daphoenus dug burrows for their offspring to stay in and hide from their prey.”

To quote Rhinehart’s paper;

“The Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Daphoenus in the southeastern United States.”

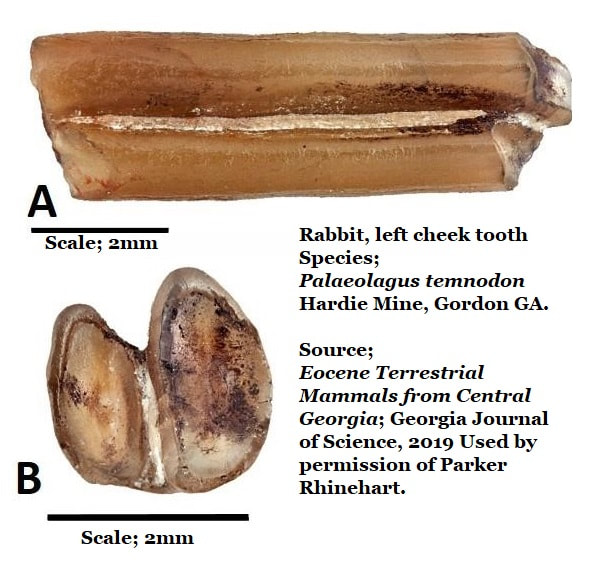

Palaeolagus temnodon (rabbit or hare)

A cheek tooth from the lower law, as imaged, was recovered from the Hardie Mine sediments which lived near Gordon, Georgia 35 million years ago. The tooth was identified by comparison with specimens in the Georgia College collection from Badlands National Park in South Dakota.

A cheek tooth from the lower law, as imaged, was recovered from the Hardie Mine sediments which lived near Gordon, Georgia 35 million years ago. The tooth was identified by comparison with specimens in the Georgia College collection from Badlands National Park in South Dakota.

This ancient hare, like modern hare, lived in a savannah, plain or woodland between fertile lands of the paleo-Ocmulgee and paleo-Oconee Rivers. No doubt it hid whenever it sensed the presence of bear-dogs.

The genus Palaeolagus lacked the highly developed hind legs which modern rabbits and hares enjoy, so it wasn’t fast by today’s standards. But, as we’ve discussed, neither was the bear-dog Daphoenus. It may well be that speed, or bursts of speed, evolved together in both prey and predators. Any advantage, no matter how small, which encourages survival and reproduction in an individual is both copied and magnified in successive generations.

There’s another important fact about this tooth from Palaeolagus temnodon. To quote Rhinehart’s paper;

“The Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Palaeolagus in the southeastern United States.”

The genus Palaeolagus lacked the highly developed hind legs which modern rabbits and hares enjoy, so it wasn’t fast by today’s standards. But, as we’ve discussed, neither was the bear-dog Daphoenus. It may well be that speed, or bursts of speed, evolved together in both prey and predators. Any advantage, no matter how small, which encourages survival and reproduction in an individual is both copied and magnified in successive generations.

There’s another important fact about this tooth from Palaeolagus temnodon. To quote Rhinehart’s paper;

“The Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Palaeolagus in the southeastern United States.”

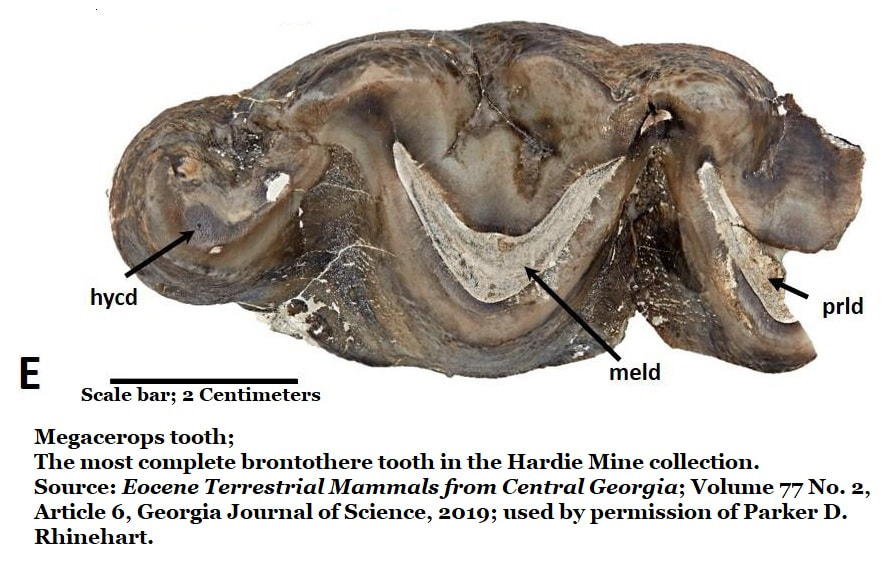

Megacerops (brontothere)

An almost complete Megacerops tooth was reported in the paper, a right molar.

An almost complete Megacerops tooth was reported in the paper, a right molar.

The Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Megacerops in the Late Eocene sediments of the southeastern United States. Though resembling a modern rhinoceros these were closer to elephant sized animals. All species and both sexes carried horns on the end of their snout, though the horns of males were much larger than females which suggests they were social animals and there was likely combat for mating rights.

To quote Rhinehart;

“…the Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Megacerops in the Late Eocene sediments of the southeastern United States.”

To quote Rhinehart;

“…the Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Megacerops in the Late Eocene sediments of the southeastern United States.”

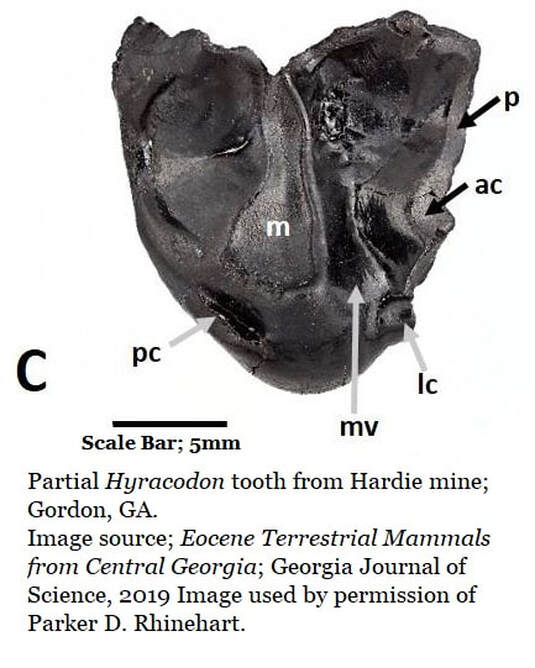

Hyracodon (hornless rhino)

Hyracodon looks somewhat like a horse, or a pony at first glance, but is in reality related to rhinoceroses. It has been described as a hornless, agile-built rhino with three toes on each foot. It was adapted towards running and was likely a browser.

Hyracodon looks somewhat like a horse, or a pony at first glance, but is in reality related to rhinoceroses. It has been described as a hornless, agile-built rhino with three toes on each foot. It was adapted towards running and was likely a browser.

The recovered tooth, though partial, shows the diagnostic characteristics of a Hyracodon. This Hardie Mine specimen represents the first known occurrence of Hyracodon in the southeastern United States.

All four of these species are fairly common in western North America but rare in the Southeast, this shows that many species were likely widespread so the hunt for fossils should continue.

All four of these species are fairly common in western North America but rare in the Southeast, this shows that many species were likely widespread so the hunt for fossils should continue.

Historically, the Clinchfiled Formation is Georgia's richest source of Cenozoic vertebrate fossils, below is a partial list with these 2019 reports added.

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency

Fish (sharks)

Lamna Appendiculate * Mackerel shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate* Great White Shark Abundant

Galecerdo latidens* Tiger Shark Abundant

Sphyrna (sp?)* Hammerhead Rare

Myliobatis (sp?)* Eagle Ray Abundant

Pristis (sp?)* Sawfish Very rare

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth

Carcharias hopei Sand/Tiger Shark 296 Teeth

Carcharias koerti Sand/Tiger Shark 123 teeth

Edaphodon (species?) 1st SE Chimaera Extremely Rare

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth

Heterodontus Angel Shark 1 Tooth

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth

Mustelus vanderhoefti (?) Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth

Mammals

Basilosaurus (sp?)* Early Whale, Large Rare

Zygorhiza* Early Whale, Smaller Rare

Eosiren (sp?)* Manatee Common

Family; Brontotherid Rhino-like mammal Very Rare

Daphoenus Bear-dog Very rare (2019)

Palaeolagus temnodon Rabbit or hare Very rare (2019)

Megacerops (sp) Rhino-like animal Very rare (2019)

Hyracodon Hornless rhino Very rare (2019)

Reptiles

Family: Cheloniidae Sea Turtles Rare

Family: Trionychinae Soft Shelled Turtles Rare

Dermochelydidae (sp?) Leather Back Turtles Rare

Nebraskophis (new Sp?) Colubrid Snake Very Rare

Palaeophis (species?) Palaeophid Snake Rare

Palaeophis africanus Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus (species?) Pterosphenus Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus schucherti Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency

Fish (sharks)

Lamna Appendiculate * Mackerel shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate* Great White Shark Abundant

Galecerdo latidens* Tiger Shark Abundant

Sphyrna (sp?)* Hammerhead Rare

Myliobatis (sp?)* Eagle Ray Abundant

Pristis (sp?)* Sawfish Very rare

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth

Carcharias hopei Sand/Tiger Shark 296 Teeth

Carcharias koerti Sand/Tiger Shark 123 teeth

Edaphodon (species?) 1st SE Chimaera Extremely Rare

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth

Heterodontus Angel Shark 1 Tooth

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth

Mustelus vanderhoefti (?) Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth

Mammals

Basilosaurus (sp?)* Early Whale, Large Rare

Zygorhiza* Early Whale, Smaller Rare

Eosiren (sp?)* Manatee Common

Family; Brontotherid Rhino-like mammal Very Rare

Daphoenus Bear-dog Very rare (2019)

Palaeolagus temnodon Rabbit or hare Very rare (2019)

Megacerops (sp) Rhino-like animal Very rare (2019)

Hyracodon Hornless rhino Very rare (2019)

Reptiles

Family: Cheloniidae Sea Turtles Rare

Family: Trionychinae Soft Shelled Turtles Rare

Dermochelydidae (sp?) Leather Back Turtles Rare

Nebraskophis (new Sp?) Colubrid Snake Very Rare

Palaeophis (species?) Palaeophid Snake Rare

Palaeophis africanus Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus (species?) Pterosphenus Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus schucherti Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Congratulations to Rhinehart, Meade and Parmley on the publication of their paper and a hearty thanks to them for expanding our knowledge of Georgia’s Fossil record.

References

- Rhinehart, Parker, D.; Mead, Alfred J.; Parmley, Dennis; Eocene Terrestrial Mammals from Central Georgia; Volume 77 No. 2, Article 6, Georgia Journal of Science, 2019