20F; A Southeastern Thermal Enclave

Glacial Ice & the Sunny South

By Thomas D. Thurman

Gators don’t like cold.

Alligators are cold-blooded reptiles. When it gets below about 60° to 70°F they’ll stop feeding. As temperatures dip on down to around 40°F they’ll retreat into a den and go dormant, waiting for warmer weather.

They can endure some cold weather, even freezing conditions for short periods. Water cools slower than air. Alligators have been known to float with their snouts just above the surface and become frozen into light surface ice, then swim away unharmed when the ice melts and frees them. But long periods of cold are fatal. (1)

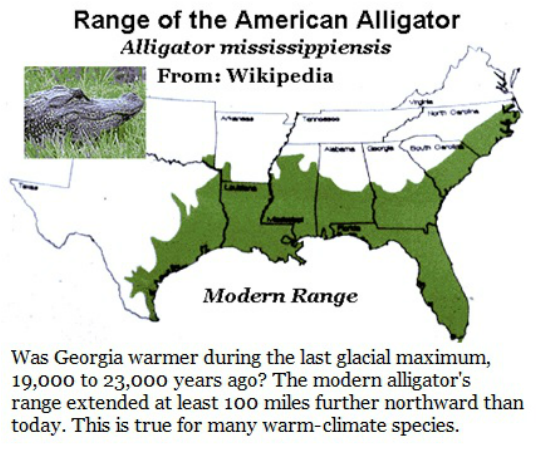

This is why their range is generally restricted to Georgia’s Coastal Plain. Winters further north defeat them. Today, the alligator’s range varies somewhat year to year depending on the severity of each winter, but it cannot tolerate the modern winters of North Georgia. They’re rarely seen north of Macon.

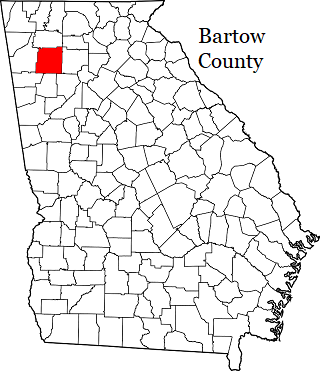

So, it’s interesting that fossils of the modern alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) occur in Northwest Georgia. These were deposited during the last glacial maximums, when North America was at its coldest. Mostly these are cave finds, likely deposited by flooding. Still, they didn't travel any great distance.

The last glacial maximum occurred between 19,000 and 23,000 years ago and at that time the alligator’s range extended more than 100 miles further north than it does today.

The alligator material and fossils from a wide variety of other species including other reptiles, amphibians, birds, fish and mammals were collected in Northwest Georgia’s Ladds Cave; Bartow County, by C. E. Ray who reported them in 1967 through the Georgia Academy of Sciences. (2)

Alligators weren't the only large warm weather reptile in Bartow County and North Carolina during the last glacial maximum. Ladds Cave also produced fossils of the extinct giant land tortoise Hesperotestudo crassiscutata. Up to six feet long, this huge tortoise would have been very similar to modern Galapagos tortoises; unable to withstand cold weather.

The last glacial maximum occurred between 19,000 and 23,000 years ago and at that time the alligator’s range extended more than 100 miles further north than it does today.

The alligator material and fossils from a wide variety of other species including other reptiles, amphibians, birds, fish and mammals were collected in Northwest Georgia’s Ladds Cave; Bartow County, by C. E. Ray who reported them in 1967 through the Georgia Academy of Sciences. (2)

Alligators weren't the only large warm weather reptile in Bartow County and North Carolina during the last glacial maximum. Ladds Cave also produced fossils of the extinct giant land tortoise Hesperotestudo crassiscutata. Up to six feet long, this huge tortoise would have been very similar to modern Galapagos tortoises; unable to withstand cold weather.

Safe from the Ice

A Thermal Enclave is a warm refuge for plants and animals during a cold glacial period. It seems that this might be the case for the Southeast, repeatedly.

One of the most interesting papers I’ve seen during my journey through Georgia’s natural history was published in 2009 by a research team including Dr. Frederick J. Rich, Professor of Geology at Georgia Southern in Statesboro, Georgia. (3) It explores the paleo environments during the last glacial period. The paper raises the hypothesis that the southeast was a thermal enclave during glacial maximums where warm climate flora and fauna could survive the cold.

I should state here that the debate lingers over this paper's premise. Warm climate animals certainly occur in northwest Georgia from this time frame, but so do cold climate caribou (reindeer).

A Thermal Enclave is a warm refuge for plants and animals during a cold glacial period. It seems that this might be the case for the Southeast, repeatedly.

One of the most interesting papers I’ve seen during my journey through Georgia’s natural history was published in 2009 by a research team including Dr. Frederick J. Rich, Professor of Geology at Georgia Southern in Statesboro, Georgia. (3) It explores the paleo environments during the last glacial period. The paper raises the hypothesis that the southeast was a thermal enclave during glacial maximums where warm climate flora and fauna could survive the cold.

I should state here that the debate lingers over this paper's premise. Warm climate animals certainly occur in northwest Georgia from this time frame, but so do cold climate caribou (reindeer).

Crocodilians in Georgia

Alligators hunted the wetlands of Bartow County long before humans walked North America. Alligator mississippiensis emerged into the fossil record about 2.5 million years ago. It is a member of the crocodilian order. The crocodilians have been in Georgia for a long time.

As reported by Dr. David Schwimmer of Columbus State University, the fossils of their kin are known to at least 77 million years ago when the genus Deinosuchus (Terrible Crocodile) occurs in the fossils of the Chattahoochee River Valley. These were giants; individuals from Texas have been estimated to a maximum of 35 feet (10.6 meters) long. (4) Dr. Schwimmer published a book on the subject entitled: King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus.

Gavialosuchus americanus, another member of the crocodilian order reaching up to 32 feet (9.75 meters) in length, also hunted Georgia about 6 million years ago.

Alligators hunted the wetlands of Bartow County long before humans walked North America. Alligator mississippiensis emerged into the fossil record about 2.5 million years ago. It is a member of the crocodilian order. The crocodilians have been in Georgia for a long time.

As reported by Dr. David Schwimmer of Columbus State University, the fossils of their kin are known to at least 77 million years ago when the genus Deinosuchus (Terrible Crocodile) occurs in the fossils of the Chattahoochee River Valley. These were giants; individuals from Texas have been estimated to a maximum of 35 feet (10.6 meters) long. (4) Dr. Schwimmer published a book on the subject entitled: King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus.

Gavialosuchus americanus, another member of the crocodilian order reaching up to 32 feet (9.75 meters) in length, also hunted Georgia about 6 million years ago.

The Thermal Enclave

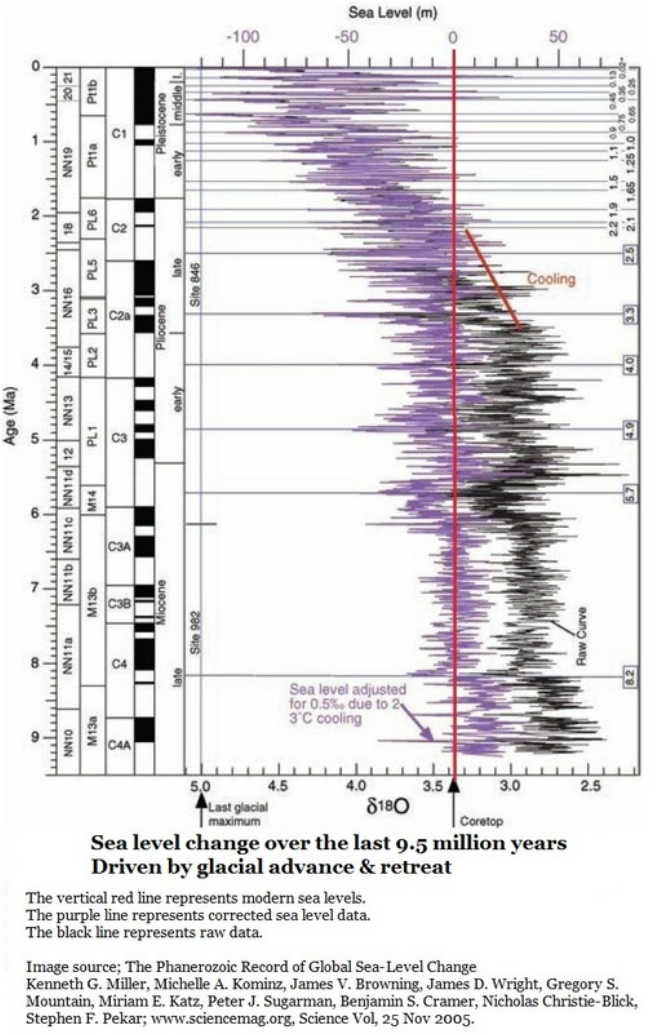

Glaciers never touched Georgia or the Southeast during the recent ice age, a time of repeated and often dramatic sea level change.

Fossils from the last glacial maximum suggests that Georgia’s climate was actually warmer than today’s and the Southeast acted as a refuge for many North American species.

Dr. Rich’s team explored the hypothesis that the Southeast represented a warm oasis from the desolate cold both north and west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Multiple research projects in multiple scientific disciplines have reviewed the fossil record and pollen samples collected from this time frame and their findings support the observation that during (at least some periods) of the last glacial maximum the Southeast was much warmer than the rest of North America.

Where most of the continent was ruled by glacial ice or extreme cold powered by glacial winds; the southeast was possibly warmer than today.

Bear in mind, a glacial maximum also means very low sea levels. Staggering amounts of water become trapped as ice. When sea water freezes the salt is pushed out. After about a year, frozen sea water will taste like freshwater.

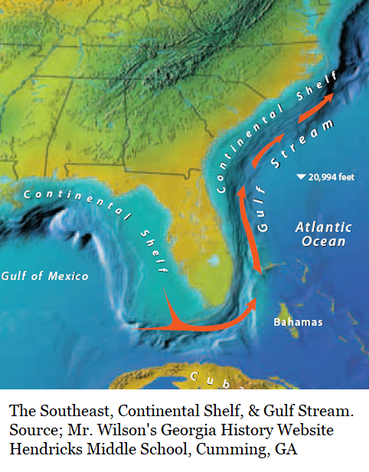

During the last glacial maximum Georgia’s coastline would have probably retreated all the way to the Continental Shelf; about 80 miles (129 kilometers) east of Savannah. Florida would have roughly tripled in size.

Warm climate plants and animals caught in the cold perished, yet these same animals and plants seemingly endured in the Southeast. It was probably the Atlantic’s Gulf Stream and the Appalachian Mountains which made the difference.

The Thermal Enclave hypothesis explains that the Atlantic’s warm Gulf Stream current possibly drove weather patterns in the Southeastern USA which were essentially contained by the Appalachian Mountains.

This allowed the alligators, and others, to thrive far north of where they cannot survive today.

During the glacial maximums there was much greater animal diversity in the Southeast than today. Fossils from both tropical and cold weather species are mixed and intermingled in the cave deposits; reindeer, alligators, giant sloths, bear-sized beavers, horses, mammoths and many others left fossils for researchers to find.

When the glaciers retreated and the rest of North America warmed again, South Georgia’s rivers became swollen with torrential, probably monsoon-like rainfall, forming the wide flood plains we see today.

The plants which had survived the glaciers in the Southeast began to return to the rest of Eastern North America and the animals were able to disperse and repopulate areas where large scale die-offs had occurred.

This likely happened repeatedly during the glacial and inter-glacial periods.

Glaciers never touched Georgia or the Southeast during the recent ice age, a time of repeated and often dramatic sea level change.

Fossils from the last glacial maximum suggests that Georgia’s climate was actually warmer than today’s and the Southeast acted as a refuge for many North American species.

Dr. Rich’s team explored the hypothesis that the Southeast represented a warm oasis from the desolate cold both north and west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Multiple research projects in multiple scientific disciplines have reviewed the fossil record and pollen samples collected from this time frame and their findings support the observation that during (at least some periods) of the last glacial maximum the Southeast was much warmer than the rest of North America.

Where most of the continent was ruled by glacial ice or extreme cold powered by glacial winds; the southeast was possibly warmer than today.

Bear in mind, a glacial maximum also means very low sea levels. Staggering amounts of water become trapped as ice. When sea water freezes the salt is pushed out. After about a year, frozen sea water will taste like freshwater.

During the last glacial maximum Georgia’s coastline would have probably retreated all the way to the Continental Shelf; about 80 miles (129 kilometers) east of Savannah. Florida would have roughly tripled in size.

Warm climate plants and animals caught in the cold perished, yet these same animals and plants seemingly endured in the Southeast. It was probably the Atlantic’s Gulf Stream and the Appalachian Mountains which made the difference.

The Thermal Enclave hypothesis explains that the Atlantic’s warm Gulf Stream current possibly drove weather patterns in the Southeastern USA which were essentially contained by the Appalachian Mountains.

This allowed the alligators, and others, to thrive far north of where they cannot survive today.

During the glacial maximums there was much greater animal diversity in the Southeast than today. Fossils from both tropical and cold weather species are mixed and intermingled in the cave deposits; reindeer, alligators, giant sloths, bear-sized beavers, horses, mammoths and many others left fossils for researchers to find.

When the glaciers retreated and the rest of North America warmed again, South Georgia’s rivers became swollen with torrential, probably monsoon-like rainfall, forming the wide flood plains we see today.

The plants which had survived the glaciers in the Southeast began to return to the rest of Eastern North America and the animals were able to disperse and repopulate areas where large scale die-offs had occurred.

This likely happened repeatedly during the glacial and inter-glacial periods.

A new find supporting the Thermal Enclave theory

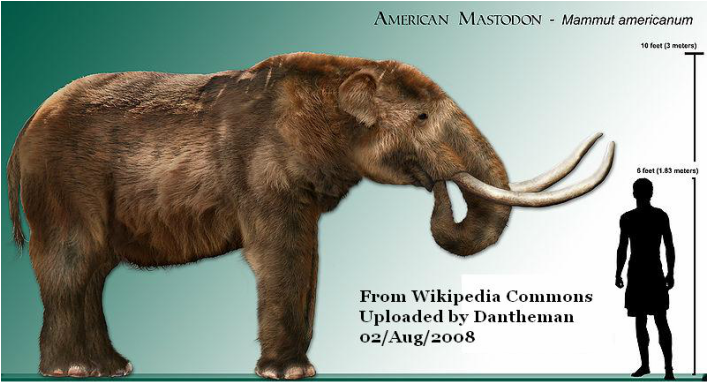

Dr. Rich isn’t finished with his work on this subject. He’s researched a new American mastodon (Mammut Americanum) find near North Charleston, South Carolina. (5)

Southeastern mastodons are well known from the paleontological literature. A single, large adult bull died in a swamp during the last glacial maximum and a wealth of plant matter was preserved as well as much of the skeleton.

Rich’s team recovered a tusk, three molars, mandibles, femur, humerus, four vertebrae, and several ribs. The fossils revealed that the animal was a large adult male between 43 and 47 years old.

When the growth rate of its tusk is compared to other individuals from the Great Lakes region, the results suggest the North Charleston bull was experiencing nutritional or environmental stress.

The treasure of this find is that a wealth of organic material, plant material, preserved in the sediments with the mastodon. The plant material revealed that the area was a mixture of forest, prairie, and swamp.

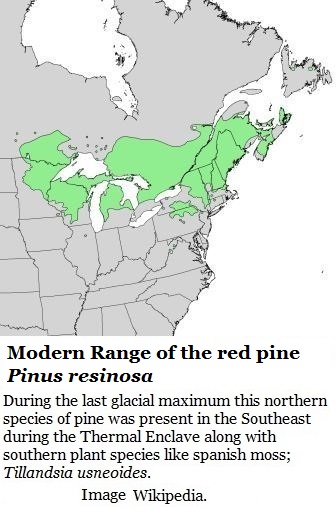

Interestingly, pollen of the red pine Pinus resinosa was present. Today this is a New England, Great Lakes, and Canadian species whose range does not extend further south than isolated populations in northern West Virginia.

The sediments also contained pollen from our native (and current) Spanish moss, several oaks, pines, and hickory. Today there is no location in North America where both red pine and Spanish moss naturally occur in the same environment.

Dr. Rich is also exploring the possibility that the megafauna extinction of the Pleistocene occurred at a faster rate here in the Southeast than elsewhere.

Dr. Rich isn’t finished with his work on this subject. He’s researched a new American mastodon (Mammut Americanum) find near North Charleston, South Carolina. (5)

Southeastern mastodons are well known from the paleontological literature. A single, large adult bull died in a swamp during the last glacial maximum and a wealth of plant matter was preserved as well as much of the skeleton.

Rich’s team recovered a tusk, three molars, mandibles, femur, humerus, four vertebrae, and several ribs. The fossils revealed that the animal was a large adult male between 43 and 47 years old.

When the growth rate of its tusk is compared to other individuals from the Great Lakes region, the results suggest the North Charleston bull was experiencing nutritional or environmental stress.

The treasure of this find is that a wealth of organic material, plant material, preserved in the sediments with the mastodon. The plant material revealed that the area was a mixture of forest, prairie, and swamp.

Interestingly, pollen of the red pine Pinus resinosa was present. Today this is a New England, Great Lakes, and Canadian species whose range does not extend further south than isolated populations in northern West Virginia.

The sediments also contained pollen from our native (and current) Spanish moss, several oaks, pines, and hickory. Today there is no location in North America where both red pine and Spanish moss naturally occur in the same environment.

Dr. Rich is also exploring the possibility that the megafauna extinction of the Pleistocene occurred at a faster rate here in the Southeast than elsewhere.

10° North

There are suspicions that the modern alligator’s range is extending northwards with global warming. Many fish populations are also showing a shift northward in search of cooler waters. The ranges of many insects and plants are shifting north. Generally researchers report a 10° northern shift in the range of many species as a response to global warming.

There are worrisome implications to this. A shift in the range of the wrong insect species could have ruinous consequences in the pollination of out agricultural crops.

Predicting the regional consequences of climate change is very difficult. When North America was at its coldest, the Southeast was at its warmest. No one expected that. These are the kinds of issues to keep in mind as we consider global warming and sea level rise. There will be surprises.

There are suspicions that the modern alligator’s range is extending northwards with global warming. Many fish populations are also showing a shift northward in search of cooler waters. The ranges of many insects and plants are shifting north. Generally researchers report a 10° northern shift in the range of many species as a response to global warming.

There are worrisome implications to this. A shift in the range of the wrong insect species could have ruinous consequences in the pollination of out agricultural crops.

Predicting the regional consequences of climate change is very difficult. When North America was at its coldest, the Southeast was at its warmest. No one expected that. These are the kinds of issues to keep in mind as we consider global warming and sea level rise. There will be surprises.

References;

1: Alligator adaptations to cold

http://animals.howstuffworks.com/reptiles/alligator5.htm

How Stuff Works; How Alligators Work

Alligator Hibernation; When it gets cold in the winter, alligators slow down. Below 70 degrees F or so they stop feeding, and when it gets much colder, alligators dig out a den in the bank of a pond or river and go dormant until it warms up again. Alligators can even survive freezing conditions. They have been known to rise to the surface if the water is about to freeze, with their nostrils above the surface. This allows them to breathe through the ice as it forms. In extreme cases, they get frozen into the surface of the pond for several days and then swim free when the ice melts.

2: RAY, C. E. (1967). Pleistocene mammals from Ladds, Bartow

County, Georgia. Georgia Academy of Science 25, 120–150.

3: Thermal Enclave

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

4: Crocodilians in Georgia 77 Million Years Ago.

Schwimmer, David R. (2002). King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–16. ISBN 0-253-34087-X.

5: South Carolina mastodon find.

Frederick J. Rich, Christine M. Brussell, Kathlyn M. Smith, and K. Mace Brown. "The Late Pleistocene Thermal Enclave: New evidence from an American Mastodon site in South Carolina, USA" Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Annual Meeting, Denver, CO 45 (2013): 322.

source:https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2013AM/webprogram/Paper231539.html

1: Alligator adaptations to cold

http://animals.howstuffworks.com/reptiles/alligator5.htm

How Stuff Works; How Alligators Work

Alligator Hibernation; When it gets cold in the winter, alligators slow down. Below 70 degrees F or so they stop feeding, and when it gets much colder, alligators dig out a den in the bank of a pond or river and go dormant until it warms up again. Alligators can even survive freezing conditions. They have been known to rise to the surface if the water is about to freeze, with their nostrils above the surface. This allows them to breathe through the ice as it forms. In extreme cases, they get frozen into the surface of the pond for several days and then swim free when the ice melts.

2: RAY, C. E. (1967). Pleistocene mammals from Ladds, Bartow

County, Georgia. Georgia Academy of Science 25, 120–150.

3: Thermal Enclave

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

4: Crocodilians in Georgia 77 Million Years Ago.

Schwimmer, David R. (2002). King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–16. ISBN 0-253-34087-X.

5: South Carolina mastodon find.

Frederick J. Rich, Christine M. Brussell, Kathlyn M. Smith, and K. Mace Brown. "The Late Pleistocene Thermal Enclave: New evidence from an American Mastodon site in South Carolina, USA" Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Annual Meeting, Denver, CO 45 (2013): 322.

source:https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2013AM/webprogram/Paper231539.html