|

|

|

17: Rise of the Whale Eating Shark

A large, terrifying predator emerged globally during the Early Miocene, about 23 million years ago, this was the whale-eating shark megalodon.

Megalodon's large teeth are well known and common in age correct marine sediments, they're widely distributed along both North American coasts, both South American coasts, throughout the Caribbean, Japan, Australia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East... And, of course, Georgia.

A large, terrifying predator emerged globally during the Early Miocene, about 23 million years ago, this was the whale-eating shark megalodon.

Megalodon's large teeth are well known and common in age correct marine sediments, they're widely distributed along both North American coasts, both South American coasts, throughout the Caribbean, Japan, Australia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East... And, of course, Georgia.

Because of those monstrous teeth, it's one of those very popular extinct animals that lends itself to fantasy and extremes in imagination. There's a whole genre of megalodon monster shark movies

Sadly this popularity has impacted the science. For an animal whose fossils are so widespread & well known, there is amazingly little agreement among paleontologists about who and what megalodon actually was.

Sadly this popularity has impacted the science. For an animal whose fossils are so widespread & well known, there is amazingly little agreement among paleontologists about who and what megalodon actually was.

Its size is still debated.

Its ancestry is still debated.

Its lifestyle is still debated.

Even its range in geologic time was debated until recently.

There were those who seriously argued it might still swim in the unexplored depths of the sea...

It doesn't; megalodon is well and truly extinct.

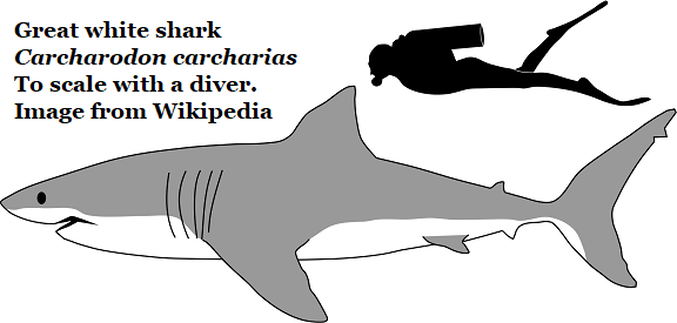

In 1843 Louis Agassiz described these giant teeth and assigned them to the species as Carcharocles megalodon placing it in the family Lamnidae and making it as a relative to the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias.

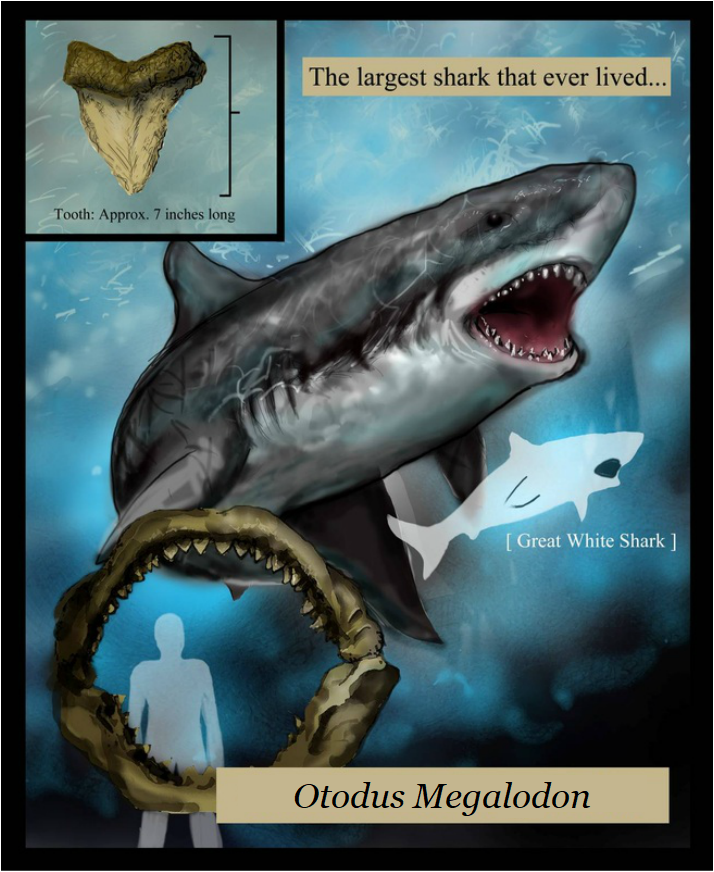

However most modern researchers accept that it has been re-assigned to the family Otodontiade and genus Otodus; thus making it Otodus megalodon.

However most modern researchers accept that it has been re-assigned to the family Otodontiade and genus Otodus; thus making it Otodus megalodon.

In the above image Otodus megalodon is depicted as a large, robust great white. This is typical. Those robust, serrated teeth clearly evolved to support magnificently powerful bites, to pierce and cut flesh and heavy bone, but reconstruction as a giant great white shark is just a best guess.

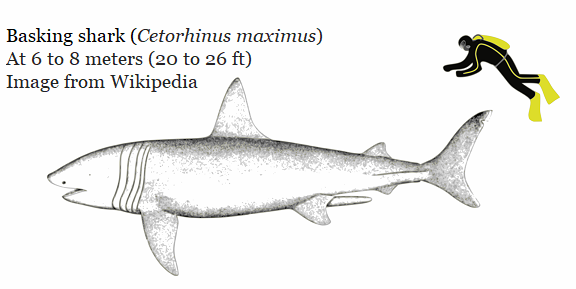

Some researchers argue that it probably looked more like the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) seen above or perhaps the sand tiger shark (Carcharias Taurus) seen below.

Size

Size estimates for an adult megalodon have also been all over the place. This is partially due to the fact that only teeth and vertebrae have ever been recovered; estimates have ranged from 10.5 meters (34ft) to 25 meters (82ft); the truth is somewhere within that range.

It certainly seems reasonable that 50ft or 60 ft megalodons existed.

Size estimates for an adult megalodon have also been all over the place. This is partially due to the fact that only teeth and vertebrae have ever been recovered; estimates have ranged from 10.5 meters (34ft) to 25 meters (82ft); the truth is somewhere within that range.

It certainly seems reasonable that 50ft or 60 ft megalodons existed.

Emergence & Extinction

Recent research explores the extinction of O. megalodon, the paleontology team below cam from both North American coast.

Robert W. Boessenecker (College of Charleston)

Dana J. Ehret (New Jersey State Museum of Natural History) Douglas J. Long (California Academy of Sciences)

Morgan Churchill (University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh)

Evan Martin (San Diego Natural History Museum)

&

Sarah J. Boessenecker (College of Charleston)

Their work silenced rumors that the giant shark still lurks in the depths of the sea.

The paper is entitled; The Early Pliocene extinction of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific.

Their research shows that O. megalodon found extinction at 3.51 million years ago, during the Late Pliocene instead of at 2.61 million years ago at the Pliocene/Pleistocene horizon, where many had previously assigned its demise.

The team reviewed many Megalodon teeth from east and west coast sediments. One issue was that teeth reported from Pleistocene sediments were typically collected where Pliocene and Pleistocene aren't distinct. As we've seen in Georgia, there are reworked beds along the Georgia coast and east coast of North America where Pliocene & Pliestocene fossils both occur. Beds created during the Pliocene, but reworked during the Pleistocene's rhythms of climate and sea level change.

When Pleistocene sea levels matched Pliocene see levels, frequently Pleistocene material fell among older Pliocene fossils. Even if the Pleistocene fossils were originally deposited in separate beds, flooding coastal rivers and changing sea levels frequently mixed Pliocene and Pleistocene fossils.

Now, while this is common on the East Coast, there are location on the North American West Coast in California & Baja Mexico where Pliocene and Pleistocene fossils were never mixed.

No megalodon tooth reviewed by the team could be confidently sourced to a bed of Pleistocene-only sediments. The most recent meg bearing bed was 3.51 million years old.

Recent research explores the extinction of O. megalodon, the paleontology team below cam from both North American coast.

Robert W. Boessenecker (College of Charleston)

Dana J. Ehret (New Jersey State Museum of Natural History) Douglas J. Long (California Academy of Sciences)

Morgan Churchill (University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh)

Evan Martin (San Diego Natural History Museum)

&

Sarah J. Boessenecker (College of Charleston)

Their work silenced rumors that the giant shark still lurks in the depths of the sea.

The paper is entitled; The Early Pliocene extinction of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific.

Their research shows that O. megalodon found extinction at 3.51 million years ago, during the Late Pliocene instead of at 2.61 million years ago at the Pliocene/Pleistocene horizon, where many had previously assigned its demise.

The team reviewed many Megalodon teeth from east and west coast sediments. One issue was that teeth reported from Pleistocene sediments were typically collected where Pliocene and Pleistocene aren't distinct. As we've seen in Georgia, there are reworked beds along the Georgia coast and east coast of North America where Pliocene & Pliestocene fossils both occur. Beds created during the Pliocene, but reworked during the Pleistocene's rhythms of climate and sea level change.

When Pleistocene sea levels matched Pliocene see levels, frequently Pleistocene material fell among older Pliocene fossils. Even if the Pleistocene fossils were originally deposited in separate beds, flooding coastal rivers and changing sea levels frequently mixed Pliocene and Pleistocene fossils.

Now, while this is common on the East Coast, there are location on the North American West Coast in California & Baja Mexico where Pliocene and Pleistocene fossils were never mixed.

No megalodon tooth reviewed by the team could be confidently sourced to a bed of Pleistocene-only sediments. The most recent meg bearing bed was 3.51 million years old.

Furthermore; the evidence suggested that the emergence of modern great whites (Carcharodon carcharias) corresponded with the demise of megalodon. Climate change created cooler surface currents and perhaps the great white shark tolerated cooler water better than megalodon.

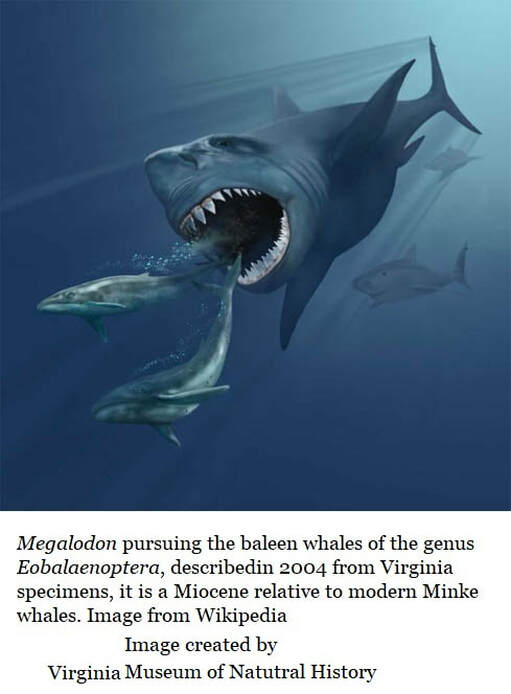

Whale Hunter

Whale fossils have been recovered with damage attributed to O. megalodon and it is thought that the shark preyed on both small and the large whales of its time. It also hunted sirens (manatees), pinnipeds (sea lions & related) and large sea turtles. It was both a coastal and deep water, warm sea predator.

It has been argued that whales were a major food source for O. megalodon and its relatives. It has even been suggested that megalodon’s

capabilities and widespread distribution might have impacted whale evolution; its presence might even have reinforced pod behavior as a defensive measure and encouraged giantism among whales.

One “law” of evolution states that any genetic adaptation, no matter how slight, which aids an individual’s quest to successfully reproduce will be passed to its offspring and magnified in its decedents.

The big sharks probably hunted alone, as do modern sharks, and it’s hard for a single predator to dispatch very large prey, so a big whale is safer from a giant shark. Under the right conditions giantism is rewarded in evolution. It is equally hard for a single predator to break up a herd or pod.

It has also been argued that megalodon influenced the current population patterns of modern whales.

The argument goes like this; the fossil record shows that originally whales were warm water predators. Yet today, whales show their greatest diversity and population densities in polar seas.

Changing global climates allowed cold water whale species to emerge and become established. O. megalodon was essentially a warm water predator; it isn’t known in cold polar environments, few sharks are cold water adapted. The modern Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) being an exception. Polar whale species were not intensely hunted by megalodon while the warm water species were.

Wikipedia reports that there is a known fossil from a 30 foot Miocene Epoch baleen whale (species un-described) which had been killed by a megalodon; it is interesting to note that the shark focused its attack on the tough shoulders, flippers, rib cage and upper spine; targets which modern great whites typically avoid. The attacking megalodon was likely attempting to cripple the whale.

In the end its size likely contributed to its downfall. Climate change probably played a large role in its extinction; global cooling with the associated fall in sea levels and redistribution of currents and waterways meant that the large warm seas, which it required, began to dwindle.

Bear in mind, climate change also contributed to the emergence of our species.

References

1: Boessenecker RW, Ehret DJ, Long DJ, Churchill M, Martin E, Boessenecker SJ. 2019. The Early Pliocene extinction

of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific. PeerJ 7:e6088 DOI 10.7717/peerj.6088

2: Wikipedia; Megalodon

1: Boessenecker RW, Ehret DJ, Long DJ, Churchill M, Martin E, Boessenecker SJ. 2019. The Early Pliocene extinction

of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific. PeerJ 7:e6088 DOI 10.7717/peerj.6088

2: Wikipedia; Megalodon