12: Basilosaurids, the First Modern Whales

By Thomas Thurman

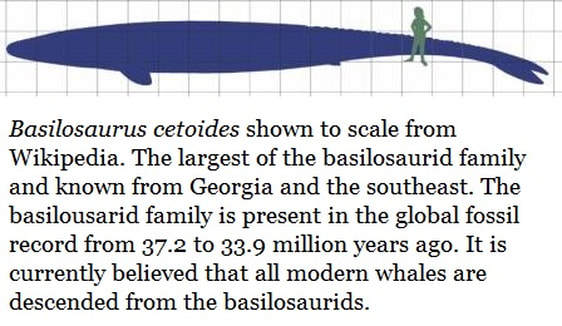

All of the basilosaurids share some common features despite significant variations in size.

Heads vary in size but share a basic layout; front teeth are peg like and distinctly banana shaped when found loose, only the tip is enameled.

Large rear teeth are triangular in shape with distinct serrations and two large, heavy roots. The jaws are narrow in front and dramatically widen in the rear. In life, the peg like front teeth were used to seize prey and the rear triangular teeth were used to dispatch and process prey.

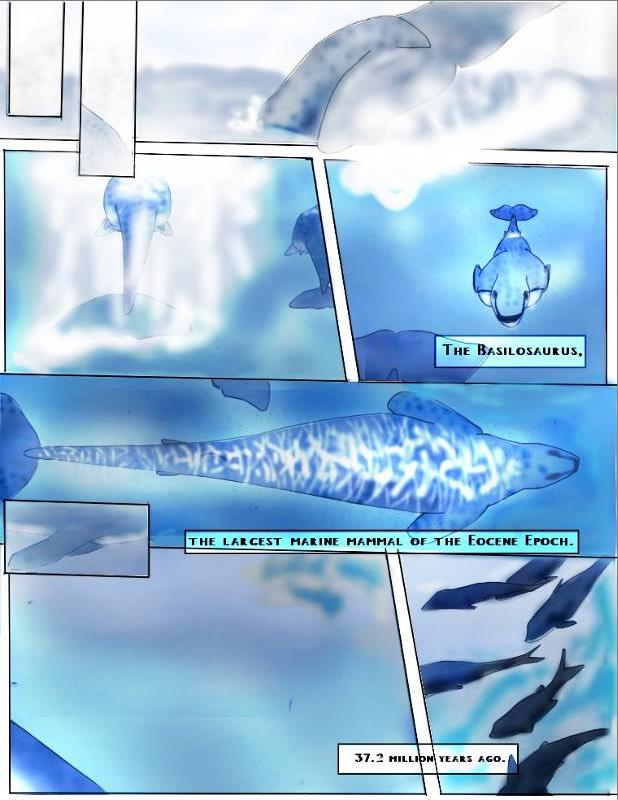

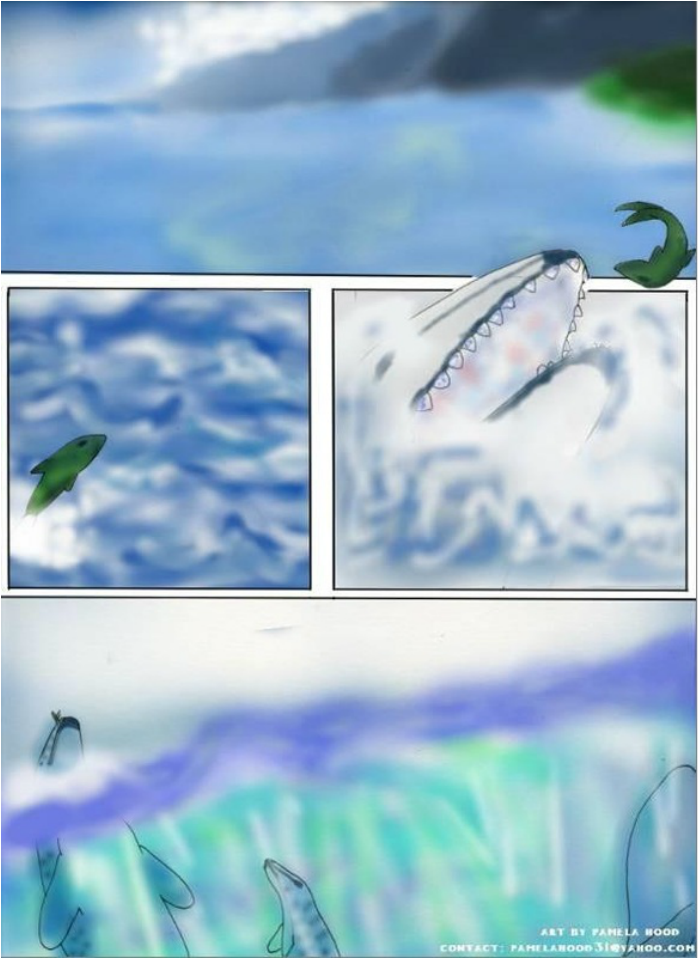

Artist Pamela Hood from Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus created these reconstructed images of Basilosaurus during a successful hunt. Notice that she has shown the atrophied rear limbs, a well-developed fluke, and blowholes just in front of the eyes. The artwork has a soft, realistic feel which gives the impression of live divers filming these large animals in the wild.

Like us, the basilosaurids have two set of teeth over their life; deciduous teeth or baby teeth, then adult teeth; so at least some information can be gleaned from the amount of wear on an adult tooth.

Basilosaurids lacked echo-location, that hadn’t yet emerged; they likely hunted by vision and sound. Some sense of smell is likely retained as well. The evidence suggests that they shared a well-developed directional sense of hearing which developed in the proto-whales

They also possessed well developed front flippers as modified front limbs and atrophied rear limbs which served no obvious function.

Pelvis bones are present and articulated with the rear limbs but detached from the spine, as we saw with Georgiacetus. Where the basilosaurids differ from Georgiacetus is the relative size of these bones; the basilosaurid pelvic arrangement is greatly reduced from the Georgiacetus arrangement.

Modern whales also retain a pelvis but it is tiny and internal, there are also several well established cases of modern dolphins possessing rear flippers, images can be found on the internet.

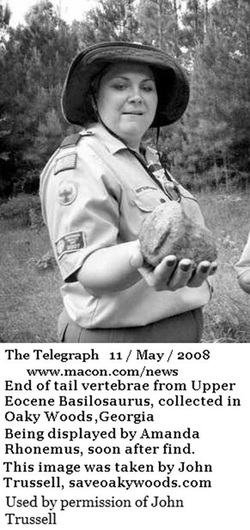

Most basilosaurids possessed flukes, there is one probable exception. There is a good fossil record showing the same greatly reduced, simplified, end-of-tail vertebra arrangement seen in modern whales; a sure indication of flukes.

Basilosaurids lacked echo-location, that hadn’t yet emerged; they likely hunted by vision and sound. Some sense of smell is likely retained as well. The evidence suggests that they shared a well-developed directional sense of hearing which developed in the proto-whales

They also possessed well developed front flippers as modified front limbs and atrophied rear limbs which served no obvious function.

Pelvis bones are present and articulated with the rear limbs but detached from the spine, as we saw with Georgiacetus. Where the basilosaurids differ from Georgiacetus is the relative size of these bones; the basilosaurid pelvic arrangement is greatly reduced from the Georgiacetus arrangement.

Modern whales also retain a pelvis but it is tiny and internal, there are also several well established cases of modern dolphins possessing rear flippers, images can be found on the internet.

Most basilosaurids possessed flukes, there is one probable exception. There is a good fossil record showing the same greatly reduced, simplified, end-of-tail vertebra arrangement seen in modern whales; a sure indication of flukes.

In May 2008 Warner Robins Cub Scout Pack Leader Amanda Rhonemus found an end-of-tail vertebra from a Basilosaurus in Oaky Woods Wildlife Management Area, Houston County, Georgia. John Trussell, a local hunter and author, was guiding the scouts on a tour when the specimen was accidentally discovered. The Macon Telegraph covered the story with picture by John Trussell on Sunday, May 11Th.

To give an idea of the true size of Basilosaurus cetoides one of the members of the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society has a single Basilosaurus vertebra, the size of a mailbox, which he collected from an overburden mound at a kaolin pit just southeast of Gordon, Georgia in Wilkinson County.

All the basilosaurids were active predators hunting warm seas. They should not be considered gentle giants as many whales are today, these were advanced apex predators.

Family Basilosauridae

This is the large basilosaurid family of basilosaurids.

Genus Basilosaurus

B. cetoides (USA: AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, & SC)

B. drazindai (Pakistan)

B. isis (Egypt, in large numbers)

B. wanklyni

B. vredensis

B. caucasicus

B. paulsoni

B. puschi

B. harwoodi (Australia?)

Genus Basilotritus (Species? Virginia)

B. wardii (North Carolina)

Genus Chrysocetus

C. helyorum (South Carolina)

Genus Cynthiacetus (Species? FL)

C. maxwelli (USA: AL, FL, GA, MS, & NC,)

Genus Dorudon

D. atrox (USA, Egypt & Pakistan)

D. serratus (Al, GA. SC, & MS)

Genus Saghacetus

S. orisis (Egypt)

Genus Zygorhiza

Z. Kochii (New Zealand, USA: AL, GA, LA, MS, NC, FL & SC)

Global Sea levels

For the duration of the Priabonian stage of the Late Eocene Epoch (37.2 through 33.9 million years ago) the global climates remained much warmer than today and sea levels were much higher. The poles were likely ice free.

There were two significant global cold snaps in this timeframe where sea levels fell but even the Priabonian low stands of sea levels were at least ten meters (32+ feet) higher than today’s average sea levels.

At 33.9 million years ago a series of dramatic, sudden episodes of global cooling triggered repeated glaciation and repetitive retreats of sea levels. In the first one coast lines fell globally perhaps 15 meters (49+ feet) below current levels. This opened the Oligocene Epoch, being warm water whales the basilosaurids did not survive this cooling period and met extinction, only to be replaced by whales better adapted and more cold tolerant.

Though they were now gone from the Earth’s seas, the basilosaurids left their legacy behind. Modern research strongly suggests that all modern whales are descended through the basilosaurids.

The Emergence of Mysticeti; the Baleen Whales

The basilosaurids did not survive into the Oligocene Epoch, but they persisted globally right up until the very end of the Eocene and diversified widely. By the end of the Eocene, the next major shift in whale evolution was underway; the earliest Mysticeti, or baleen whales, occur.

The baleen whales could have emerged anywhere but nearly all of the earliest Mysticeti occur in the Southern hemisphere where their greatest diversity still persists. Llanocetus denticrenatus was discovered in the latest Eocene sediments of Seymour Island, Antarctica and current research puts it as the earliest known Mysticeti or baleen whale.

Llanocetus was a large animal with a 2 meter (6.5 foot) long head and a body length of perhaps 30 feet (9.1 meters). It was excavated in the mid-1970s and described by E. D. Mitchell in 1989 in a paper entitled; A New Cetacean from the Late Eocene La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula., which was published in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science. You can see the skull in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington.

While not a baleen whale in the modern sense, Llanocetus is toothed in the familiar basilosaurid arrangement of forward peg-like teeth and large rear molars. It shares so many traits with the basilosaurids that close relationship is assured, but there is a distinct adaptation in the molars which strongly suggest filter feeding.

The generally triangular shape and twin roots are present as they are in all basilosaurids; but the molars are proportionally smaller than generally seen in whales of a similar size. Also, what are serration-like denticles on the basilosaurid molars are greatly exaggerated in Llanocetus to the level of suggesting a palm frond or an open hand with stubby fingers.

Researchers believe a primitive form of baleen was present in Llanocetus. Baleen; which is made of material very similar to your fingernails, isn’t recorded in the fossils of Llanocetus and rarely fossilizes at all. However, these odd molars possessed evidence of an unusually high blood supply and in the living animal the molars would have been covered by the gums.

The evidence suggests that primitive baleen were present in the living animal. There are also adaptations in the skull which would have allowed deep diving, so Llanocetus may have taken krill, small fish and of small prey deep and the forced the water out of its mouth and fed on what remained. Krill represents one of the single largest amounts of biomass on Earth.

Odontoceti; The Emergence of Echolocation

Though it isn’t yet reported from Georgia the earliest known toothed whale to likely possess echolocation is the whale sub-family Squalodontidae, generally about 10 feet (3 meters) in length, they emerged during the Oligocene Epoch roughly 33 million years ago.

The Paleobiology Data Base (paleobiodb.org) reports professionally published squalodon family finds from both Florida and South Carolina, so it’s probably just a matter of time before there is a Georgia report. They have additionally been reported from the United States’ East, West and Gulf Coasts, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Chile, Costa Rica, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Mexico, The Netherlands, Sicily, Switzerland, and Venezuela.

The most famous member is Squalodon which looked very much like a modern dolphin except for a greatly elongated snout. The word Squalodon means “shark tooth whale” referring to the triangular shape of its molars. Other members of the sub-family had shorter snouts. Squalodon, and all members of its sub-family, possessed a single blowhole located at the peak of the skull between the eyes, as in modern dolphins. This is a trait shared by all toothed whales.

They are the oldest known cetaceans to possess a melon, or the organ which modern toothed whales, the Odontoceti, use to generate the sounds for their echolocation.

The sub-family also retained the basic tooth arrangement of the basilosaurids, banana shaped peg-like teeth forward and triangular, double rooted, serrated molars rear. So their direct relationship to the basilosaurids is evident. That full spread of peg teeth known in modern toothed whales had not yet emerged.

All earlier whales and all modern baleen whales possess two nostrils or blowholes; modern baleen whales retain a sense of smell, probably directional smell. All modern toothed whales possess a single nostril or blowhole with the other nostril adapted towards sound generation and routed through their melon. Modern toothed whales seemingly possess no sense of smell, a sense of smell is of very limited use if it isn’t directional and a single nostril cannot produce a directional sense of smell.

The melon is a soft tissue organ on the forehead, just in front of the eyes. Toothed whale skulls show a distinct “hollow” where the melon rests and becomes the primary sense organ, it’s the melon which gives dolphins, killer whales and beaked whales their rounded forehead, and gives sperm whales that great blunt head.

In echolocation, sounds, typically clicks and whistles, are generated in the sinus then amplified, focused and broadcast through the melon. The echoes returning to the whale are then processed into a mental image of their surroundings, just like our eyes process a mental image of our surrounding. Echolocation becomes the whale’s primary sense.

Superb underwater hearing is the other piece the echolocation puzzle, adaptations towards improved underwater hearing began early on with the proto-whales, bone induction hearing, where the lower jaw has become linked to the ear and greatly increases general hearing and directional underwater. The basilosaurids had greatly improved hearing over earlier whales, but modern toothed whales have hearing that is far superior to the basilosaurids.

Squalodon seems to fall somewhere in between, hearing improved from the basilosaurids but not as acute as modern tooth whales. The presence of a melon means Squalodon could very probably echolocate, it had all the tools, but modern whales are dolphins are probably much more capable in echolocation than was Squalodon.

In modern whales acute directional hearing and the melon combine in echolocation to produce some of the ocean’s top predators. It is easily one of the most powerful hunting tools ever developed by evolution.

References:

Basilosaurid Evolution

A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013

Age of the Twiggs Clay

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

To give an idea of the true size of Basilosaurus cetoides one of the members of the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society has a single Basilosaurus vertebra, the size of a mailbox, which he collected from an overburden mound at a kaolin pit just southeast of Gordon, Georgia in Wilkinson County.

All the basilosaurids were active predators hunting warm seas. They should not be considered gentle giants as many whales are today, these were advanced apex predators.

Family Basilosauridae

This is the large basilosaurid family of basilosaurids.

Genus Basilosaurus

B. cetoides (USA: AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, & SC)

B. drazindai (Pakistan)

B. isis (Egypt, in large numbers)

B. wanklyni

B. vredensis

B. caucasicus

B. paulsoni

B. puschi

B. harwoodi (Australia?)

Genus Basilotritus (Species? Virginia)

B. wardii (North Carolina)

Genus Chrysocetus

C. helyorum (South Carolina)

Genus Cynthiacetus (Species? FL)

C. maxwelli (USA: AL, FL, GA, MS, & NC,)

Genus Dorudon

D. atrox (USA, Egypt & Pakistan)

D. serratus (Al, GA. SC, & MS)

Genus Saghacetus

S. orisis (Egypt)

Genus Zygorhiza

Z. Kochii (New Zealand, USA: AL, GA, LA, MS, NC, FL & SC)

Global Sea levels

For the duration of the Priabonian stage of the Late Eocene Epoch (37.2 through 33.9 million years ago) the global climates remained much warmer than today and sea levels were much higher. The poles were likely ice free.

There were two significant global cold snaps in this timeframe where sea levels fell but even the Priabonian low stands of sea levels were at least ten meters (32+ feet) higher than today’s average sea levels.

At 33.9 million years ago a series of dramatic, sudden episodes of global cooling triggered repeated glaciation and repetitive retreats of sea levels. In the first one coast lines fell globally perhaps 15 meters (49+ feet) below current levels. This opened the Oligocene Epoch, being warm water whales the basilosaurids did not survive this cooling period and met extinction, only to be replaced by whales better adapted and more cold tolerant.

Though they were now gone from the Earth’s seas, the basilosaurids left their legacy behind. Modern research strongly suggests that all modern whales are descended through the basilosaurids.

The Emergence of Mysticeti; the Baleen Whales

The basilosaurids did not survive into the Oligocene Epoch, but they persisted globally right up until the very end of the Eocene and diversified widely. By the end of the Eocene, the next major shift in whale evolution was underway; the earliest Mysticeti, or baleen whales, occur.

The baleen whales could have emerged anywhere but nearly all of the earliest Mysticeti occur in the Southern hemisphere where their greatest diversity still persists. Llanocetus denticrenatus was discovered in the latest Eocene sediments of Seymour Island, Antarctica and current research puts it as the earliest known Mysticeti or baleen whale.

Llanocetus was a large animal with a 2 meter (6.5 foot) long head and a body length of perhaps 30 feet (9.1 meters). It was excavated in the mid-1970s and described by E. D. Mitchell in 1989 in a paper entitled; A New Cetacean from the Late Eocene La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula., which was published in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science. You can see the skull in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington.

While not a baleen whale in the modern sense, Llanocetus is toothed in the familiar basilosaurid arrangement of forward peg-like teeth and large rear molars. It shares so many traits with the basilosaurids that close relationship is assured, but there is a distinct adaptation in the molars which strongly suggest filter feeding.

The generally triangular shape and twin roots are present as they are in all basilosaurids; but the molars are proportionally smaller than generally seen in whales of a similar size. Also, what are serration-like denticles on the basilosaurid molars are greatly exaggerated in Llanocetus to the level of suggesting a palm frond or an open hand with stubby fingers.

Researchers believe a primitive form of baleen was present in Llanocetus. Baleen; which is made of material very similar to your fingernails, isn’t recorded in the fossils of Llanocetus and rarely fossilizes at all. However, these odd molars possessed evidence of an unusually high blood supply and in the living animal the molars would have been covered by the gums.

The evidence suggests that primitive baleen were present in the living animal. There are also adaptations in the skull which would have allowed deep diving, so Llanocetus may have taken krill, small fish and of small prey deep and the forced the water out of its mouth and fed on what remained. Krill represents one of the single largest amounts of biomass on Earth.

Odontoceti; The Emergence of Echolocation

Though it isn’t yet reported from Georgia the earliest known toothed whale to likely possess echolocation is the whale sub-family Squalodontidae, generally about 10 feet (3 meters) in length, they emerged during the Oligocene Epoch roughly 33 million years ago.

The Paleobiology Data Base (paleobiodb.org) reports professionally published squalodon family finds from both Florida and South Carolina, so it’s probably just a matter of time before there is a Georgia report. They have additionally been reported from the United States’ East, West and Gulf Coasts, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Chile, Costa Rica, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Mexico, The Netherlands, Sicily, Switzerland, and Venezuela.

The most famous member is Squalodon which looked very much like a modern dolphin except for a greatly elongated snout. The word Squalodon means “shark tooth whale” referring to the triangular shape of its molars. Other members of the sub-family had shorter snouts. Squalodon, and all members of its sub-family, possessed a single blowhole located at the peak of the skull between the eyes, as in modern dolphins. This is a trait shared by all toothed whales.

They are the oldest known cetaceans to possess a melon, or the organ which modern toothed whales, the Odontoceti, use to generate the sounds for their echolocation.

The sub-family also retained the basic tooth arrangement of the basilosaurids, banana shaped peg-like teeth forward and triangular, double rooted, serrated molars rear. So their direct relationship to the basilosaurids is evident. That full spread of peg teeth known in modern toothed whales had not yet emerged.

All earlier whales and all modern baleen whales possess two nostrils or blowholes; modern baleen whales retain a sense of smell, probably directional smell. All modern toothed whales possess a single nostril or blowhole with the other nostril adapted towards sound generation and routed through their melon. Modern toothed whales seemingly possess no sense of smell, a sense of smell is of very limited use if it isn’t directional and a single nostril cannot produce a directional sense of smell.

The melon is a soft tissue organ on the forehead, just in front of the eyes. Toothed whale skulls show a distinct “hollow” where the melon rests and becomes the primary sense organ, it’s the melon which gives dolphins, killer whales and beaked whales their rounded forehead, and gives sperm whales that great blunt head.

In echolocation, sounds, typically clicks and whistles, are generated in the sinus then amplified, focused and broadcast through the melon. The echoes returning to the whale are then processed into a mental image of their surroundings, just like our eyes process a mental image of our surrounding. Echolocation becomes the whale’s primary sense.

Superb underwater hearing is the other piece the echolocation puzzle, adaptations towards improved underwater hearing began early on with the proto-whales, bone induction hearing, where the lower jaw has become linked to the ear and greatly increases general hearing and directional underwater. The basilosaurids had greatly improved hearing over earlier whales, but modern toothed whales have hearing that is far superior to the basilosaurids.

Squalodon seems to fall somewhere in between, hearing improved from the basilosaurids but not as acute as modern tooth whales. The presence of a melon means Squalodon could very probably echolocate, it had all the tools, but modern whales are dolphins are probably much more capable in echolocation than was Squalodon.

In modern whales acute directional hearing and the melon combine in echolocation to produce some of the ocean’s top predators. It is easily one of the most powerful hunting tools ever developed by evolution.

References:

Basilosaurid Evolution

A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013

Age of the Twiggs Clay

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996