14A: The Late Eocene Coastal Plain

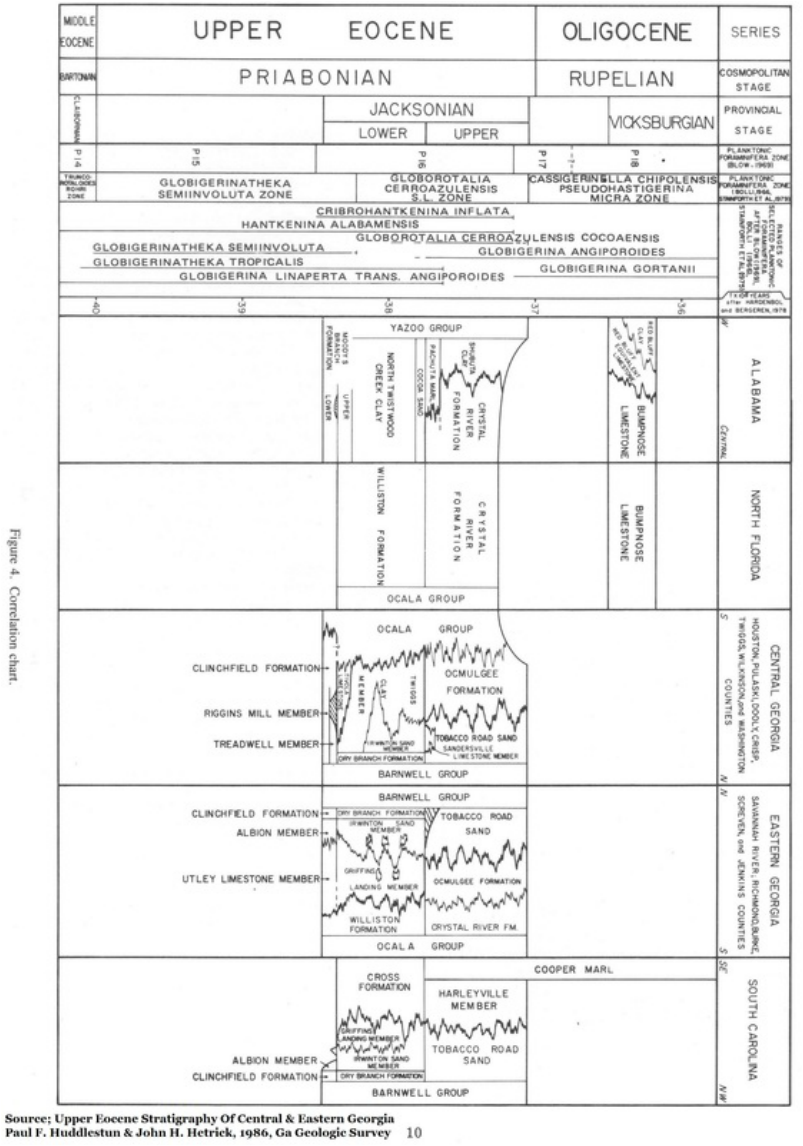

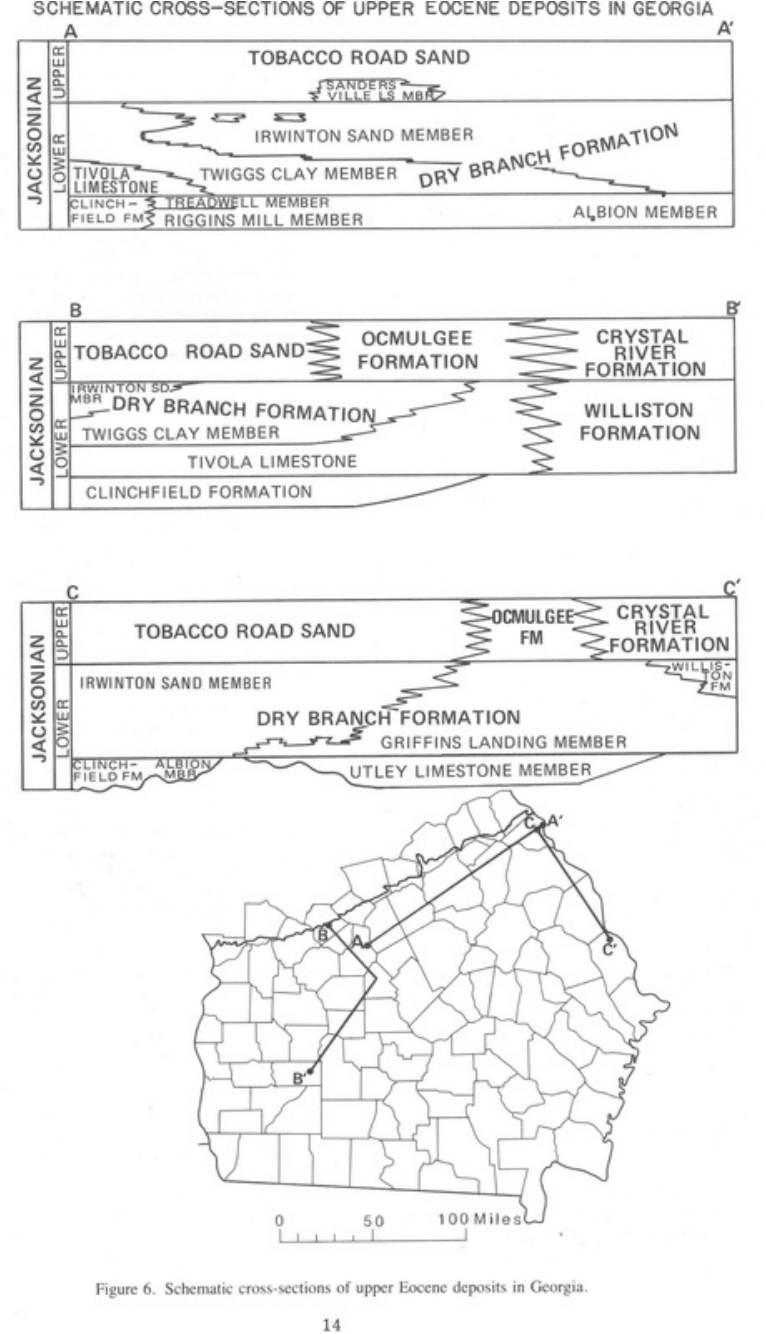

Researchers have been studying Georgia’s extremely complex Coastal Plain sediments for more than a century, dozens of papers have been published on the subject and each paper answers many mysteries but reveals even more.

I have tried to be as precise as possible, but the truth is that without a solid understanding sea level changes and the processes of deposition and erosion it is difficult to grasp the Coastal Plain.

The stratigraphy of Houston County is well understood and this is somewhat in the center of Georgia and the northern Coastal Plain; go 20 miles in any direction and everything changes.

Take Tivola Limestone in Houston County; it averages about forty feet thick and is almost entirely marine in character; formed by the fossils of tiny marine organism. Underneath it (underlying) is the Clinchfield Formation going down for perhaps thirty feet is a terrestrial-source formation of mostly quartz sand deposited by rivers. On top of the Tivola Limestone (overlying) is the Twiggs Clay at nearly one hundred feet thick, depending on your location, and it is also a terrestrial-sourced formation made up of inland clays and silt deposited by the same rivers.

Get in your car and drive twenty miles east and you’ll find both the Twiggs Clay and the Clinchfield Formation, but the Tivola becomes sporadic.

I have tried to be as precise as possible, but the truth is that without a solid understanding sea level changes and the processes of deposition and erosion it is difficult to grasp the Coastal Plain.

The stratigraphy of Houston County is well understood and this is somewhat in the center of Georgia and the northern Coastal Plain; go 20 miles in any direction and everything changes.

Take Tivola Limestone in Houston County; it averages about forty feet thick and is almost entirely marine in character; formed by the fossils of tiny marine organism. Underneath it (underlying) is the Clinchfield Formation going down for perhaps thirty feet is a terrestrial-source formation of mostly quartz sand deposited by rivers. On top of the Tivola Limestone (overlying) is the Twiggs Clay at nearly one hundred feet thick, depending on your location, and it is also a terrestrial-sourced formation made up of inland clays and silt deposited by the same rivers.

Get in your car and drive twenty miles east and you’ll find both the Twiggs Clay and the Clinchfield Formation, but the Tivola becomes sporadic.

Returning for a moment to sea level change, deposition and erosion; bear in mind that Georgia is a land of several large flowing rivers. These rivers are ancient and were present during all this sea level change.

Advancing coastlines reached the Fall Line and further north repeatedly, then fell again all the way (at times) to the continental shelf. Our rivers endured through all of this, but their courses and estuaries shifted with sea levels.

The characteristics of the rivers also changed; sometimes they were thick with sand, sometimes they were thick with clay and silt; sometimes then ran clear. Even within the beds of any given formation repeated change in river conditions is often evident. Rivers, of course, carry terrestrial sediments; sediments whose origins are inland. In the case of our rivers and the Late Eocene formations we’re discussing, these sediments are terrestrial sediments deposited in a marine, coastal environment where the rivers become estuaries emptying into the sea.

The separate beds of sediments within any given formation might reflect local, regional or global changes in conditions while they were being deposited. These changes might be minimal, or major. Since many of the Middle Georgia marine deposits are influenced by local rivers flowing into the sea the sediments could either be terrestrial or marine. A bed might reflect the passing of a storm or a drought. It could represent a red tide episode. A landslide one hundred miles inland might be recorded in the coastal sediments of an estuary.

If an impact event or volcanic eruption occurs regionally or globally it can often be dated by finding which bed contains debris from associated tsunamis, impact ejecta, or ash. The formations are like chapters in a history book, the beds are like pages in the chapters.

This is stratigraphy, the geologic study of layers. In the case of the Coastal Plain this study is almost always about sedimentary rock, of deposition and erosion. Earth not only writes its history in the rock, it also erases portions of that history.

The thickness of a bed doesn’t necessarily have any bearing on how long it took to deposit it; rather it reflects conditions, how fast deposition occurred and how much material was present.

Advancing coastlines reached the Fall Line and further north repeatedly, then fell again all the way (at times) to the continental shelf. Our rivers endured through all of this, but their courses and estuaries shifted with sea levels.

The characteristics of the rivers also changed; sometimes they were thick with sand, sometimes they were thick with clay and silt; sometimes then ran clear. Even within the beds of any given formation repeated change in river conditions is often evident. Rivers, of course, carry terrestrial sediments; sediments whose origins are inland. In the case of our rivers and the Late Eocene formations we’re discussing, these sediments are terrestrial sediments deposited in a marine, coastal environment where the rivers become estuaries emptying into the sea.

The separate beds of sediments within any given formation might reflect local, regional or global changes in conditions while they were being deposited. These changes might be minimal, or major. Since many of the Middle Georgia marine deposits are influenced by local rivers flowing into the sea the sediments could either be terrestrial or marine. A bed might reflect the passing of a storm or a drought. It could represent a red tide episode. A landslide one hundred miles inland might be recorded in the coastal sediments of an estuary.

If an impact event or volcanic eruption occurs regionally or globally it can often be dated by finding which bed contains debris from associated tsunamis, impact ejecta, or ash. The formations are like chapters in a history book, the beds are like pages in the chapters.

This is stratigraphy, the geologic study of layers. In the case of the Coastal Plain this study is almost always about sedimentary rock, of deposition and erosion. Earth not only writes its history in the rock, it also erases portions of that history.

The thickness of a bed doesn’t necessarily have any bearing on how long it took to deposit it; rather it reflects conditions, how fast deposition occurred and how much material was present.

Clinchfield Formation

The Clinchfield Formation breaks down into four members (or variants);

The Riggins Mill Member

The Treadwell Member

The Albion Member

The Utley Member

There is no room to cover all three here and many of the reports for Clinchfield Formation fossils predate their separation in the literature. Since there is no way to know which member produced these older reported finds we’ll treat the three members together here.

The Clinchfield Formation represents Georgia’s most widespread, vertebrate fossil bearing sediments from the Eocene Epoch. It ranges from South Carolina to Roberta, Georgia.

The Roberta, Georgia location at Rich Hill is approximately 177 miles inland from the modern coastline, Veatch and Stephenson reviewed Rich Hill but in 1911 the wasn’t yet named, it was not recognized as a separate formation. They did comment that it held abundant shark’s teeth.

In several locations it overlies kaolin deposits; it is frequently exposed during kaolin mining operations. Surface exposures are very rare but do occur in Houston County.

In 1970 Sam Pickering surveyed the Clinchfield Formation in Middle Georgia and also commented that it was rich in vertebrate fossils. He assigned the name Clinchfield Sand following a 1965 oral report from Dr. Michael Voorhies, a paleontologist with the University of Georgia at the time whose work we’ve reviewed.

Previous to this the formation had been referred to as the Gosport Sand by work done in 1943 and referenced to sediments in Alabama. Pickering and Voorhies disagreed with the Gopsort correlation with Alabama and raised the Clinchfield Sand to independent formation status.

Later, in 1986 Paul Huddlestun revised this and changed the name to the Clinchfield Formation, then subdivided that into the current four variants.

In 2005 Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College’s Natural History Museum surveyed the Clinchfield Formation’s vertebrate fossils in the inactive Hardie Mine kaolin quarry near Gordon, Georgia.

His research produced several scientifically important fossils including thousands of shark’s teeth; several species of turtle shell fossils, the oldest North American colubrid constrictor family of snake, extinct members of the boa constrictor and anaconda families with both adults and young present; individual vertebra fossils were found from adults suggesting snake lengths of 15ft.

The Clinchfield Formation breaks down into four members (or variants);

The Riggins Mill Member

The Treadwell Member

The Albion Member

The Utley Member

There is no room to cover all three here and many of the reports for Clinchfield Formation fossils predate their separation in the literature. Since there is no way to know which member produced these older reported finds we’ll treat the three members together here.

The Clinchfield Formation represents Georgia’s most widespread, vertebrate fossil bearing sediments from the Eocene Epoch. It ranges from South Carolina to Roberta, Georgia.

The Roberta, Georgia location at Rich Hill is approximately 177 miles inland from the modern coastline, Veatch and Stephenson reviewed Rich Hill but in 1911 the wasn’t yet named, it was not recognized as a separate formation. They did comment that it held abundant shark’s teeth.

In several locations it overlies kaolin deposits; it is frequently exposed during kaolin mining operations. Surface exposures are very rare but do occur in Houston County.

In 1970 Sam Pickering surveyed the Clinchfield Formation in Middle Georgia and also commented that it was rich in vertebrate fossils. He assigned the name Clinchfield Sand following a 1965 oral report from Dr. Michael Voorhies, a paleontologist with the University of Georgia at the time whose work we’ve reviewed.

Previous to this the formation had been referred to as the Gosport Sand by work done in 1943 and referenced to sediments in Alabama. Pickering and Voorhies disagreed with the Gopsort correlation with Alabama and raised the Clinchfield Sand to independent formation status.

Later, in 1986 Paul Huddlestun revised this and changed the name to the Clinchfield Formation, then subdivided that into the current four variants.

In 2005 Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College’s Natural History Museum surveyed the Clinchfield Formation’s vertebrate fossils in the inactive Hardie Mine kaolin quarry near Gordon, Georgia.

His research produced several scientifically important fossils including thousands of shark’s teeth; several species of turtle shell fossils, the oldest North American colubrid constrictor family of snake, extinct members of the boa constrictor and anaconda families with both adults and young present; individual vertebra fossils were found from adults suggesting snake lengths of 15ft.

Georgia Auk

Dr. Parmley’s research also produced an unusual bird fossil, a single small humerus (wing bone). Dr. Robert Chandler, also from Georgia College, was asked to share his expertise in bird evolution in reviewing this specimen.

The humerus Dr. Parmley recovered turned out to be from the oldest known North American auk. This was surprising since all specimens from this mine in Gordon are warm climate, even subtropical animals. Up until the discovery of this bone it had been thought that auks must have evolved in cold water environments.

Auks are small diving birds which swim with their wings; flying over the waves the spot their prey, dive into the sea and pursue. It was believed that birds which swim with their wings had to evolve in cold waters where fish could not swim as fast as they can in warm waters.

The presence of this Georgia auk bone in a tropical or sub-tropical environment has forced a re-think of the evolution of auks; perhaps all bird which swim with their wings.

Dr. Parmley’s research also produced an unusual bird fossil, a single small humerus (wing bone). Dr. Robert Chandler, also from Georgia College, was asked to share his expertise in bird evolution in reviewing this specimen.

The humerus Dr. Parmley recovered turned out to be from the oldest known North American auk. This was surprising since all specimens from this mine in Gordon are warm climate, even subtropical animals. Up until the discovery of this bone it had been thought that auks must have evolved in cold water environments.

Auks are small diving birds which swim with their wings; flying over the waves the spot their prey, dive into the sea and pursue. It was believed that birds which swim with their wings had to evolve in cold waters where fish could not swim as fast as they can in warm waters.

The presence of this Georgia auk bone in a tropical or sub-tropical environment has forced a re-think of the evolution of auks; perhaps all bird which swim with their wings.

Brontothere

Parmley’s research also produced Georgia’s first brontothere fossil (meaning thunder beast, also known as a titanothere).

This was a large, rhinoceros-like land mammal related to horses. Imagine a rhino with a v-shaped horn on its snout. (Though in truth it was not a horn but a bony extension of the skull covered in skin.)

Brontothere fossils are well known from South Dakota and Nebraska where large herds were killed off quickly by volcanic eruptions and left an extensive fossil record, butthey were unknown in Georgia until this find.

I would like to thank the artists Quentin Lonon for this 2011 reconstruction for family Brontotheriidae, genus Megacerops though which genus or species occurred in the Clinchfield Formation is unknown. As seen, this was a large animal which was widespread in North America during the Late Eocene Epoch (say 33 to 40 million years ago) but did not did not survive the global climate change and extinction event which began the Oligocene. As a grazer, it’s believed that the tender grasses which fed large herds of these animals died back during the drier, cooler opening phases of the Oligocene and led to the extinction of the animal.

The wealth of fossils from the Gordon, Georgia area allows the reconstruction of a warm coastal Georgia environment from 35 million years ago, 155 miles inland from the nearest modern shoreline.

Parmley’s research also produced Georgia’s first brontothere fossil (meaning thunder beast, also known as a titanothere).

This was a large, rhinoceros-like land mammal related to horses. Imagine a rhino with a v-shaped horn on its snout. (Though in truth it was not a horn but a bony extension of the skull covered in skin.)

Brontothere fossils are well known from South Dakota and Nebraska where large herds were killed off quickly by volcanic eruptions and left an extensive fossil record, butthey were unknown in Georgia until this find.

I would like to thank the artists Quentin Lonon for this 2011 reconstruction for family Brontotheriidae, genus Megacerops though which genus or species occurred in the Clinchfield Formation is unknown. As seen, this was a large animal which was widespread in North America during the Late Eocene Epoch (say 33 to 40 million years ago) but did not did not survive the global climate change and extinction event which began the Oligocene. As a grazer, it’s believed that the tender grasses which fed large herds of these animals died back during the drier, cooler opening phases of the Oligocene and led to the extinction of the animal.

The wealth of fossils from the Gordon, Georgia area allows the reconstruction of a warm coastal Georgia environment from 35 million years ago, 155 miles inland from the nearest modern shoreline.

Reported Clinchfield Formation Vertebrates:

(*) After species name notes 1970 reports from Sam Pickering

All others are from 2005 & reported by Dr. Dennis Parmley and David J. Cicimurri. Dr. Parmley and David Cicimurri included tooth counts in their paper. (Source: Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Georgia Journal of Science, 2003

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency

Lamna appendiculata * Mackerel shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate* Great White Shark Abundant

Galecerdo latidens* Tiger Shark Abundant

Sphyrna (sp?)* Hammerhead Rare

Myliobatis (sp?)* Eagle Ray Abundant

Pristis (sp?)* Sawfish Very rare

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth

Carcharias hopei Sand/Tiger Shark 296 Teeth

Carcharias koerti Sand/Tiger Shark 123 teeth

Edaphodon (species?) 1st SE Chimaera Very Rare

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth

Heterodontus Angel Shark 1 Tooth

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth

Mustelus vanderhoefti (?) Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth

Basilosaurus (sp?)* Early Whale, Large Rare

Zygorhiza* Early Whale, Smaller Rare

Eosiren (sp?)* Manatee Common

Family; Brontotherid Rhino-like mammal Very Rare

Family: Alcidae Bird; Auk Very Rare

Family: Cheloniidae Sea Turtles Rare

Family: Trionychinae Soft Shelled Turtles Rare

Dermochelydidae (sp?) Leather Back Turtles Rare

Nebraskophis (new Sp?) NA Colubrid Snake Very Rare

Palaeophis (species?) Palaeophid Snake Rare

Palaeophis africanus Large Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus (species?) Marine Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus schucherti Large Marine Snake Very Rare

(*) After species name notes 1970 reports from Sam Pickering

All others are from 2005 & reported by Dr. Dennis Parmley and David J. Cicimurri. Dr. Parmley and David Cicimurri included tooth counts in their paper. (Source: Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Georgia Journal of Science, 2003

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency

Lamna appendiculata * Mackerel shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate* Great White Shark Abundant

Galecerdo latidens* Tiger Shark Abundant

Sphyrna (sp?)* Hammerhead Rare

Myliobatis (sp?)* Eagle Ray Abundant

Pristis (sp?)* Sawfish Very rare

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth

Carcharias hopei Sand/Tiger Shark 296 Teeth

Carcharias koerti Sand/Tiger Shark 123 teeth

Edaphodon (species?) 1st SE Chimaera Very Rare

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth

Heterodontus Angel Shark 1 Tooth

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth

Mustelus vanderhoefti (?) Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth

Basilosaurus (sp?)* Early Whale, Large Rare

Zygorhiza* Early Whale, Smaller Rare

Eosiren (sp?)* Manatee Common

Family; Brontotherid Rhino-like mammal Very Rare

Family: Alcidae Bird; Auk Very Rare

Family: Cheloniidae Sea Turtles Rare

Family: Trionychinae Soft Shelled Turtles Rare

Dermochelydidae (sp?) Leather Back Turtles Rare

Nebraskophis (new Sp?) NA Colubrid Snake Very Rare

Palaeophis (species?) Palaeophid Snake Rare

Palaeophis africanus Large Constrictor Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus (species?) Marine Snake Very Rare

Pterosphenus schucherti Large Marine Snake Very Rare

As a note:

Pickering’s 1970 report (page 20) included finding specimens of the mega-tooth shark, megalodon in two Eocene Epoch formations. We’ll look at this animal in more detail later. This was a mistake in identification as megalodon didn’t emerge until the Late Oligocene Epoch; millions of years after these formations had been laid down. The report is interesting in the fact that Pickering lists occurrence frequency, implying multiple specimens might have been recovered, I asked Sam Pickering about this when I visited him in 2011 but he didn’t recall how many specimens were recovered and his notes had been lost decades earlier when he left the Georgia Geologic Survey.

I spoke with Ashley Quinn, Museum Manager at the Georgia College Natural History Museum and she led me to one of their displays explaining that there were mega-toothed sharks present in Georgia’s Eocene seas, notably Carcharodon auriculatus. The museum has one of the teeth on display; it so resembles a megalodon tooth in both size and basic shape that the author would probably make the same mistake during a field identification.

Pickering’s 1970 record for Eocene megalodon finds

Genus &/or Species Common Clinchfield Form. Tivola Limestone

Carcharodon megalodon Giant Shark Rare Very Rare

This is assumed to be

Carcharodon auriculatus Giant Shark Rare Very Rare

Pickering’s 1970 report (page 20) included finding specimens of the mega-tooth shark, megalodon in two Eocene Epoch formations. We’ll look at this animal in more detail later. This was a mistake in identification as megalodon didn’t emerge until the Late Oligocene Epoch; millions of years after these formations had been laid down. The report is interesting in the fact that Pickering lists occurrence frequency, implying multiple specimens might have been recovered, I asked Sam Pickering about this when I visited him in 2011 but he didn’t recall how many specimens were recovered and his notes had been lost decades earlier when he left the Georgia Geologic Survey.

I spoke with Ashley Quinn, Museum Manager at the Georgia College Natural History Museum and she led me to one of their displays explaining that there were mega-toothed sharks present in Georgia’s Eocene seas, notably Carcharodon auriculatus. The museum has one of the teeth on display; it so resembles a megalodon tooth in both size and basic shape that the author would probably make the same mistake during a field identification.

Pickering’s 1970 record for Eocene megalodon finds

Genus &/or Species Common Clinchfield Form. Tivola Limestone

Carcharodon megalodon Giant Shark Rare Very Rare

This is assumed to be

Carcharodon auriculatus Giant Shark Rare Very Rare

Sirens (Manatees)

The siren family, of which the Florida manatee is a member, is most closely related to elephants and is also known from the Clinchfield Formation and the Tivola Limestone.

Their oldest known appearance in the fossil record comes from Jamaica about 40 million years ago with Prorastomus sirenoides, which was pig sized animal with four legs.

By 34 million years ago the sirens had evolved into fully marine animals. By 24 million years ago their current 2 genres had emerged. Two other genres are known but extinct. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History holds siren fossils collected in 1935 from Houston County’s Clinchfield formation. This is of interest as during the 1980s Smithsonian researchers reviewing siren evolution would come to the University of Georgia to review manatee fossils and make an important discovery about another Eocene mammal.

The siren family, of which the Florida manatee is a member, is most closely related to elephants and is also known from the Clinchfield Formation and the Tivola Limestone.

Their oldest known appearance in the fossil record comes from Jamaica about 40 million years ago with Prorastomus sirenoides, which was pig sized animal with four legs.

By 34 million years ago the sirens had evolved into fully marine animals. By 24 million years ago their current 2 genres had emerged. Two other genres are known but extinct. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History holds siren fossils collected in 1935 from Houston County’s Clinchfield formation. This is of interest as during the 1980s Smithsonian researchers reviewing siren evolution would come to the University of Georgia to review manatee fossils and make an important discovery about another Eocene mammal.

Tivola Limestone

The Tivola limestone is slightly younger than the Clinchfield Formation and overlies it in Houston County. It is a soft, rough, richly fossiliferous limestone occurring in outcrop or shallow subsurface deposit in Crawford, Bibb, Pulaski, Houston, Bleckley, Twiggs and Wilkinson Counties.

It was formerly known as the Ocala Limestone. In many locations it is absent, due to erosion or non-deposition.

The thickness, where present, can be from a few inches to more than 42 feet.

It has been actively mined for more than a century. Fresh exposures are light tan to light gray and can be composed almost entirely bryozoan debris, sand is also often present in varying small quantities. In its purest form the limestone can be more than 93% calcium carbonate, meaning the formation is made of small marine shell debris and reacts to acid, even vinegar.

Such bryozoan remains can be so dominant that the Tivola can become bryozoan limestone.

It darkens and hardens as it weathers and can appear as nearly black in old exposures. Echinoids in the form of abundant sand dollars occur, specifically Periarchus pileussinensis, near the top of the Tivola these echinoids can often be found in numbers, stocked in living positions like pancakes.

The Tivola is a strongly marine formation. Where the underlying Clinchfield Formation and overlying Twiggs Clay Formation are both comprised of terrestrial material deposited in a marine environment, the Tivola is almost completely made of marine material, with sand being very minor.

It is also considered an off shore formation with sediments laid down in a high energy environment. (Large fragments are common.) In most of the Tivola’s thickness the fossils are found in all positions, and often as partial remains. This shows that they originated elsewhere and were transported and deposited by strong currents.

Near the top a change in conditions is seen which indicates a quieting of the currents. Where echinoids occurred in all positions, now they tend to be upright and in living positions with clusters of individuals often present, suggesting that these died in their current positions.

The Tivola limestone is slightly younger than the Clinchfield Formation and overlies it in Houston County. It is a soft, rough, richly fossiliferous limestone occurring in outcrop or shallow subsurface deposit in Crawford, Bibb, Pulaski, Houston, Bleckley, Twiggs and Wilkinson Counties.

It was formerly known as the Ocala Limestone. In many locations it is absent, due to erosion or non-deposition.

The thickness, where present, can be from a few inches to more than 42 feet.

It has been actively mined for more than a century. Fresh exposures are light tan to light gray and can be composed almost entirely bryozoan debris, sand is also often present in varying small quantities. In its purest form the limestone can be more than 93% calcium carbonate, meaning the formation is made of small marine shell debris and reacts to acid, even vinegar.

Such bryozoan remains can be so dominant that the Tivola can become bryozoan limestone.

It darkens and hardens as it weathers and can appear as nearly black in old exposures. Echinoids in the form of abundant sand dollars occur, specifically Periarchus pileussinensis, near the top of the Tivola these echinoids can often be found in numbers, stocked in living positions like pancakes.

The Tivola is a strongly marine formation. Where the underlying Clinchfield Formation and overlying Twiggs Clay Formation are both comprised of terrestrial material deposited in a marine environment, the Tivola is almost completely made of marine material, with sand being very minor.

It is also considered an off shore formation with sediments laid down in a high energy environment. (Large fragments are common.) In most of the Tivola’s thickness the fossils are found in all positions, and often as partial remains. This shows that they originated elsewhere and were transported and deposited by strong currents.

Near the top a change in conditions is seen which indicates a quieting of the currents. Where echinoids occurred in all positions, now they tend to be upright and in living positions with clusters of individuals often present, suggesting that these died in their current positions.

Below are the Tivola Limestone vertebrate Fossil records from multiple sources;

Georgia Geologic Survey; Sam Pickering 1970 (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Rare

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Carcharodon megalodon Megatooth Very Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Common

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Siren (species?) Manatee (rib fragments) Rare

Dr. Michael Voorhies University of Georgia (1982)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Family Entelodont Terminator pig Very Rare

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Tivola Limestone vertebrates (as Ocala Limestone in these records)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen - County Collected by

Carcharhinus (species?) Requiem shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Cretolamna (species?) Mackerel shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Galeorhinus (species?) Hound shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Hemipristis (species?) Snaggletooth shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Odontaspis (species?) Sand Shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Sphyraena (species?) Barracuda Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Barnwell Formation vertebrates (Land Mammal)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen- County Collected by

Leptotragulus medius Camelid Tooth & jaw-Jefferson McCallie

Georgia Geologic Survey; Sam Pickering 1970 (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Rare

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Carcharodon megalodon Megatooth Very Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Common

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Siren (species?) Manatee (rib fragments) Rare

Dr. Michael Voorhies University of Georgia (1982)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Family Entelodont Terminator pig Very Rare

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Tivola Limestone vertebrates (as Ocala Limestone in these records)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen - County Collected by

Carcharhinus (species?) Requiem shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Cretolamna (species?) Mackerel shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Galeorhinus (species?) Hound shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Hemipristis (species?) Snaggletooth shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Odontaspis (species?) Sand Shark Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Sphyraena (species?) Barracuda Tooth - Twiggs Bill Christy

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Barnwell Formation vertebrates (Land Mammal)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen- County Collected by

Leptotragulus medius Camelid Tooth & jaw-Jefferson McCallie

Leptotragulus medius

Leptotragulus medius; this interesting report come from a time when both the Tivola Limestone & Clinchfield Formation designated as parts the Barnwell group of formations; today only the Clinchfield is considered part of the Barnwell Group with the Tivola held as parts of the Ocala Group of Florida.

Samuel W. McCallie was the Georgia State Geologist from 1908 to 1933; this was during the Stephenson and Veatch research project. McCallie collected the Leptotragulus medius from Jefferson County and gave it to the Smithsonian (specimen #PAL 244447). The material included a partial left mandible and two (forward) premolar teeth (P3 & P4).

A member of the Protoceratidae family L. medius was an even toed ungulate; meaning that the animal walked on two hooves per foot, as do pigs, goats and deer. They were herbivores.

They resembled deer though they were smaller and more closely related to camels. We don’t know a great deal about this particular species but the genus Leptotragulus emerged during the Eocene Epoch and went extinct with the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event, enduring for 6.3 million years (40.2 to 33.9 million years ago). Estimates put the weight for members of this genus at less than 13.6 kilograms (30 pounds) for an adult.

Leptotragulus medius; this interesting report come from a time when both the Tivola Limestone & Clinchfield Formation designated as parts the Barnwell group of formations; today only the Clinchfield is considered part of the Barnwell Group with the Tivola held as parts of the Ocala Group of Florida.

Samuel W. McCallie was the Georgia State Geologist from 1908 to 1933; this was during the Stephenson and Veatch research project. McCallie collected the Leptotragulus medius from Jefferson County and gave it to the Smithsonian (specimen #PAL 244447). The material included a partial left mandible and two (forward) premolar teeth (P3 & P4).

A member of the Protoceratidae family L. medius was an even toed ungulate; meaning that the animal walked on two hooves per foot, as do pigs, goats and deer. They were herbivores.

They resembled deer though they were smaller and more closely related to camels. We don’t know a great deal about this particular species but the genus Leptotragulus emerged during the Eocene Epoch and went extinct with the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event, enduring for 6.3 million years (40.2 to 33.9 million years ago). Estimates put the weight for members of this genus at less than 13.6 kilograms (30 pounds) for an adult.

Dry Branch Formation

The Dry Branch Formation, named for the community of Dry Branch, Georgia on the Bibb County, Twiggs County line. It consists of three distinct members;

The Twiggs Clay

The Irwinton Sand

The Griffins Landing

As a whole the Dry Branch Formation extends from Dooly County in the southwest part of the state into the South Carolina counties of Lexington and Orangeburg; northwards to very near the Fall Line and well southward as shallow subsurface.

Twiggs Clay Member, Dry Branch Formation

The Twiggs Clay overlies the Tivola Limestone in many parts of central Georgia; it too is Late Eocene Formation, being slightly younger than the Tivola Limestone. It is nearly pure, fine grained marine clay up to 100 feet thick in areas. It is known to bear vertebrate material, fish teeth and scales and (rarely) whale bones. Of course it was the Twiggs Clay which produced Ziggy (Dorudon serratus) at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA.

The Twiggs Clay overlies the Tivola Limestone in many parts of central Georgia; it too is Late Eocene Formation, being slightly younger than the Tivola Limestone. It is nearly pure, fine grained marine clay up to 100 feet thick in areas. It is known to bear vertebrate material, fish teeth and scales and (rarely) whale bones. Of course it was the Twiggs Clay which produced Ziggy (Dorudon serratus) at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA.

Irwinton Sand Member, Dry Branch Formation

This is typically a distinctly bedded sand and sand-clay sediment overlying the Twiggs Clay in Twiggs, Washington and Wilkinson Counties of Georgia. It can be fine to medium grained almost pure quartz sand. Fossils are generally rare but can be found as chert and chert cemented sandstone as well as shell fragments of clams and oysters.

This is typically a distinctly bedded sand and sand-clay sediment overlying the Twiggs Clay in Twiggs, Washington and Wilkinson Counties of Georgia. It can be fine to medium grained almost pure quartz sand. Fossils are generally rare but can be found as chert and chert cemented sandstone as well as shell fragments of clams and oysters.

Griffins Landing Member, Dry Branch Formation

This is typically a fairly well sorted, massive to vaguely and rudely bedded hardened sand seen in Burke County, Georgia as well as isolated points in parts of east-central Georgia. Limestone and clay beds occur; fossils include oysters shell beds (Crassostrea gigantissiam) and other shells.

Generally speaking these divisions of the Dry Branch Formation weren’t recognized historically and fossils in collections labeled as Twiggs Clay probably originated from the Twiggs Clay Member of Dry Branch Formation.

Specimens from the Irwinton Sand and Griffins Landing Members would have been specified as Late Eocene undifferentiated or residuum.

This is typically a fairly well sorted, massive to vaguely and rudely bedded hardened sand seen in Burke County, Georgia as well as isolated points in parts of east-central Georgia. Limestone and clay beds occur; fossils include oysters shell beds (Crassostrea gigantissiam) and other shells.

Generally speaking these divisions of the Dry Branch Formation weren’t recognized historically and fossils in collections labeled as Twiggs Clay probably originated from the Twiggs Clay Member of Dry Branch Formation.

Specimens from the Irwinton Sand and Griffins Landing Members would have been specified as Late Eocene undifferentiated or residuum.

Twiggs Clay Vertebrate Species

Twiggs Clay Vertebrates reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate Great White (Warm Seas) Abundant

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Common

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Eosiren (species?) Manatee Rare

Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College and State University adds:

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Carcharocles auriculatus Megatooth Shark Rare

The author (Thomas Thurman) adds:

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Ptychodus (species?) Extinct Ray-like Shark Rare

(Observed in road cut along Elko Road in Houston County.)

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York maintains a national online catalog of vertebrate species. For the Twiggs Clay the AMNH lists:

Location: Huber Mine (Now KaMin) Huber Pit #1

Genus & Species Common name Finds Reported

Lamna twiggsensis Mackerel shark 2 teeth Gerard R. Case

Ginglymostoma obliquum Nurse shark 2 teeth Gerard R. Case

Odontaspis acutissima Sand shark 3 teeth Gerard R. Case

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 3 snout teeth Gerard R. Case

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray 8 teeth Gerard R. Case

Location: Huber Mine (Now KaMin) Huber Pit #2

Genus & Species Common name Finds Reported by

Scyliorhinus enniskilleni Catshark 10 teeth Gerard R. Case

Hemipristis wyattdurhami Snaggletooth shark 5 teeth Gerard R. Case

Negaprion eurybathrodon Requiem shark 5 teeth Gerard R. Case

The AMNH also list for Huber (No pit location given):

Genus & Species Common name Finds Catalog#

Pterosphenus (species?) Constrictor snake Vertebra FR 7167

Twiggs Clay Vertebrates reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate Great White (Warm Seas) Abundant

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Common

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Eosiren (species?) Manatee Rare

Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College and State University adds:

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Carcharocles auriculatus Megatooth Shark Rare

The author (Thomas Thurman) adds:

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Ptychodus (species?) Extinct Ray-like Shark Rare

(Observed in road cut along Elko Road in Houston County.)

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York maintains a national online catalog of vertebrate species. For the Twiggs Clay the AMNH lists:

Location: Huber Mine (Now KaMin) Huber Pit #1

Genus & Species Common name Finds Reported

Lamna twiggsensis Mackerel shark 2 teeth Gerard R. Case

Ginglymostoma obliquum Nurse shark 2 teeth Gerard R. Case

Odontaspis acutissima Sand shark 3 teeth Gerard R. Case

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 3 snout teeth Gerard R. Case

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray 8 teeth Gerard R. Case

Location: Huber Mine (Now KaMin) Huber Pit #2

Genus & Species Common name Finds Reported by

Scyliorhinus enniskilleni Catshark 10 teeth Gerard R. Case

Hemipristis wyattdurhami Snaggletooth shark 5 teeth Gerard R. Case

Negaprion eurybathrodon Requiem shark 5 teeth Gerard R. Case

The AMNH also list for Huber (No pit location given):

Genus & Species Common name Finds Catalog#

Pterosphenus (species?) Constrictor snake Vertebra FR 7167

Ocmulgee Formation

The Ocmulgee Formation frequently occurs directly on top of the Twiggs Clay Member of the Dry Branch Formation but it’s a little sporadic in appearance. Sam Pickering knew this as the Cooper Marl in his 1970 survey; that name has been overturned and the Ocmulgee Formation is now accepted.

Considered to a near shore formation the Ocmulgee is a sandy, glauconitic (glauconite; a green clay mineral containing iron & potassium) limestone. It is highly variable and much harder than the more frequently exposed Tivola.

Typically it is composed of alternating beds, varying in thickness, of hard and soft limestone, overall the formation ranges up t0 15 meters (50ft) thick. It is typically fossiliferous throughout with many layers being highly fossiliferous with invertebrates in living positions. The sandier portions tend to be less fossiliferous, though the author has collected crab claws and sand dollars even from these.

With the Ocmulgee Formation we are looking at the uppermost Eocene Epoch exposure of the Coastal Plain. Climbing up through the Coastal Plain sediments the next formation would belong to the Oligocene Epoch.

The Ocmulgee Formation frequently occurs directly on top of the Twiggs Clay Member of the Dry Branch Formation but it’s a little sporadic in appearance. Sam Pickering knew this as the Cooper Marl in his 1970 survey; that name has been overturned and the Ocmulgee Formation is now accepted.

Considered to a near shore formation the Ocmulgee is a sandy, glauconitic (glauconite; a green clay mineral containing iron & potassium) limestone. It is highly variable and much harder than the more frequently exposed Tivola.

Typically it is composed of alternating beds, varying in thickness, of hard and soft limestone, overall the formation ranges up t0 15 meters (50ft) thick. It is typically fossiliferous throughout with many layers being highly fossiliferous with invertebrates in living positions. The sandier portions tend to be less fossiliferous, though the author has collected crab claws and sand dollars even from these.

With the Ocmulgee Formation we are looking at the uppermost Eocene Epoch exposure of the Coastal Plain. Climbing up through the Coastal Plain sediments the next formation would belong to the Oligocene Epoch.

Sam Pickering reported the below Ocmulgee vertebrate occurrences:

Ocmulgee Formation Vertebrates reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Common

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Smithsonian; Eocene

The below files lack detailed stratigraphic location so they are presented here, many of the records are also repetitive, the same species collected at different times by different researchers, so here they are consolidated to present a record of what’s present in Georgia’s Eocene sediments:

The below files lack detailed stratigraphic location so they are presented here, many of the records are also repetitive, the same species collected at different times by different researchers, so here they are consolidated to present a record of what’s present in Georgia’s Eocene sediments:

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Common

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Common

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Eocene Vertebrates from Georgia

Online Catalog: Search the Department of Paleobiology Collections

Downloaded: 7/April/2013

Genus & Species Common name Location Specimen

Order: Testudines Turtle Wilkinson County 34 shell frag.

Family: Mesonychidae Mesonychid Crisp County Partial Femur

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish Bibb County Dermal bones

Protosiren (species?) Siren/Manatee Houston County Partial rib

Eocene Vertebrates from Georgia

Online Catalog: Search the Department of Paleobiology Collections

Downloaded: 7/April/2013

Genus & Species Common name Location Specimen

Order: Testudines Turtle Wilkinson County 34 shell frag.

Family: Mesonychidae Mesonychid Crisp County Partial Femur

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish Bibb County Dermal bones

Protosiren (species?) Siren/Manatee Houston County Partial rib

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Eocene Vertebrates from Georgia

Online Catalog: Search the Department of Paleobiology Collections

Downloaded: 7/April/2013

Genus & Species Common name Location Specimen

Order: Testudines Turtle Wilkinson County 34 shell frag.

Family: Mesonychidae Mesonychid Crisp County Partial Femur

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish Bibb County Dermal bones

Protosiren (species?) Siren/Manatee Houston County Partial rib

Eocene Vertebrates from Georgia

Online Catalog: Search the Department of Paleobiology Collections

Downloaded: 7/April/2013

Genus & Species Common name Location Specimen

Order: Testudines Turtle Wilkinson County 34 shell frag.

Family: Mesonychidae Mesonychid Crisp County Partial Femur

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish Bibb County Dermal bones

Protosiren (species?) Siren/Manatee Houston County Partial rib

Mesonychids are essentially medium to large hoofed predators. The earliest species walked flat on their toes, by the Late Eocene they likely walked on hooves. Called wolves-with-hooves they were effective predators, probably capable of taking large prey and were adapted to running.

This is the only report of mesonychids in Georgia which the author has seen. Several species are known through North America. Mesonychids emerged in the Paleocene Epoch 55 to 60 million years ago but went extinct in the Early Oligocene around 33 million years ago.

This is the only report of mesonychids in Georgia which the author has seen. Several species are known through North America. Mesonychids emerged in the Paleocene Epoch 55 to 60 million years ago but went extinct in the Early Oligocene around 33 million years ago.

References:

· Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central and Eastern Georgia. Paul F. Huddlestun and John H. Hetrick. Bulletin 95. Georgia Geologic Survey. 1986

· Stratigraphy, Paleontology and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia. Sam M. Pickering Jr. Bulletin 81. Georgia Geological Survey. 1970

· Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Dennis Parmley, David J. Cicimurri. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.61, Pgs 153-179, 2003. Georgia Academy of Sciences

· Diverse Turtle Fauna from the Late Eocene of Georgia Including the Oldest Records of Aquatic Testudinoids in Southeastern North America. Dennis Parmley, J. Howard Hutchinson and James F. Parham. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 43, No.3, Pgs. 343-350. 2006. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

· Size and Age Class estimates of North American Eocene Palaeopheid Snakes. Dennis Parmley & Harold W. Reed. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol. 61, pgs. 220-232. Georgia Academy of Sciences.

· Nebraskophis Holman From The Late Eocene of Georgia (USA), the Oldest Known North American Colubrid Snake. Pennis Parmley and J. Alan Holman. Acta Zoologica Cracoviensai Vol. 46, pgs. 1-8, 2003

· First Record of a Chimaeroid Fish from the Eocene of the Southeastern United States. Dennis Parmley and David J. Cicimurri. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.79. pgs, 1219-1221. 2005 The Paleontological Society.

· Palaeopheid Snakes from the late Eocene Hardie Mine Local fauna of Central Georgia. Dennis Parmley and Melanie DeVore. Southeastern Naturalist, Vol.4, No.4, pgs. 703-722. 2005.

· Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central and Eastern Georgia. Paul F. Huddlestun and John H. Hetrick. Bulletin 95. Georgia Geologic Survey. 1986

· Stratigraphy, Paleontology and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia. Sam M. Pickering Jr. Bulletin 81. Georgia Geological Survey. 1970

· Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Dennis Parmley, David J. Cicimurri. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.61, Pgs 153-179, 2003. Georgia Academy of Sciences

· Diverse Turtle Fauna from the Late Eocene of Georgia Including the Oldest Records of Aquatic Testudinoids in Southeastern North America. Dennis Parmley, J. Howard Hutchinson and James F. Parham. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 43, No.3, Pgs. 343-350. 2006. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

· Size and Age Class estimates of North American Eocene Palaeopheid Snakes. Dennis Parmley & Harold W. Reed. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol. 61, pgs. 220-232. Georgia Academy of Sciences.

· Nebraskophis Holman From The Late Eocene of Georgia (USA), the Oldest Known North American Colubrid Snake. Pennis Parmley and J. Alan Holman. Acta Zoologica Cracoviensai Vol. 46, pgs. 1-8, 2003

· First Record of a Chimaeroid Fish from the Eocene of the Southeastern United States. Dennis Parmley and David J. Cicimurri. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.79. pgs, 1219-1221. 2005 The Paleontological Society.

· Palaeopheid Snakes from the late Eocene Hardie Mine Local fauna of Central Georgia. Dennis Parmley and Melanie DeVore. Southeastern Naturalist, Vol.4, No.4, pgs. 703-722. 2005.