12C; Cynthiacetus maxwelli

Crisp County’s

Late Eocene Whale

Residing in the Smithsonian

By Thomas Thurman

Revised 06/March/2021

Georgia’s Crisp County Whale Fossils

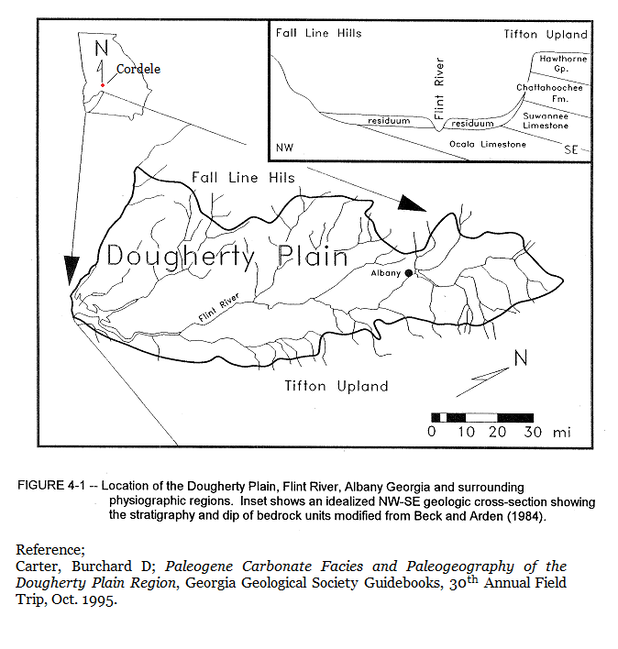

Despite an official record of two individuals in the Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org), a single Cynthiacetus maxwelli occurs unquestioningly in Georgia’s natural history. It was discovered a few miles from Cordele, in Crisp County and is represented by six vertebrae collected in 1925 from what in now Lake Blackshear. They’re held in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

I want to thank the Resources page of the Paleontology Association of Georgia's website for showing the Cynthiacetus record in Georgia and leading me on this quest. A link to the resource page is below.

paleoassocga.wixsite.com/home/resources?fbclid=IwAR21X4MTMznFq3MN5ae-lHKo_G48_De9Vqeaf6ImvisBDQa-XMNJunFtXyo

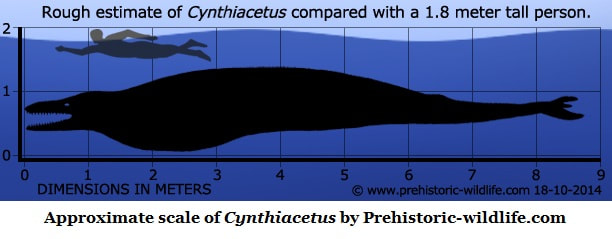

Cynthiacetus is a member of the basilosaurid family of great whales and swam the Coastal Plain sea submerging South Georgia during the Late Eocene. The Crisp County whale lived 34 million years ago. It was a large, very capable predator with savage teeth. At 8.5 meters (27 feet) it was killer whale sized. Its skull exceeds a meter in length, which is significantly longer than a killer whale skull, and the teeth of Cynthiacetus are evolved to shear prey into manageable chunks. They make the teeth of the modern killer whale look rather simple.

The natural history of Cynthiacetus is something of a Gordian Knot within the greater Gordian Knot of Georgia’s geologic history. Sometimes, all you can do is plunge into the rabbit hole and start the journey.

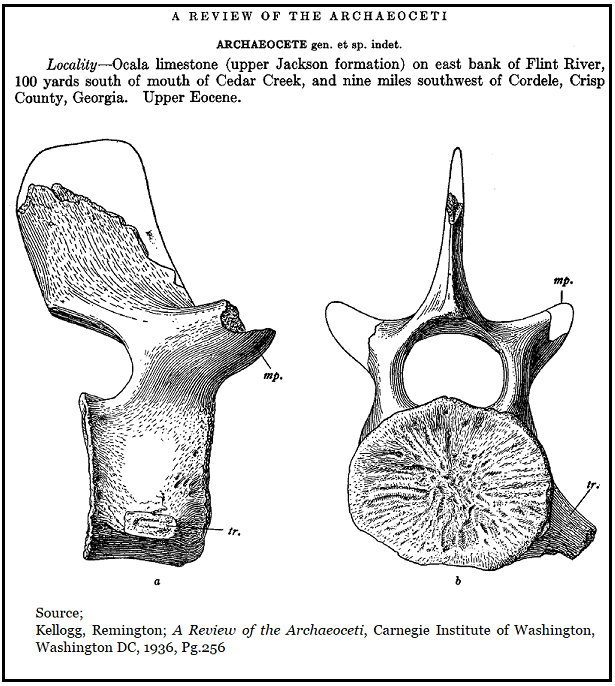

Wythe Cook 1925

Georgia’s history of Cynthiacetus begins on October 11th, 1925 when paleontologist C. Wythe Cooke collected six largish whale lumbar vertebrae from a limestone outcrop in Crisp County along the eastern bank of the Flint River, about 100 yards south of where Cedar Creek once flowed into the Flint. This is roughly nine miles west-southwest of Cordele, Georgia. (1,pg.256)

Georgia’s history of Cynthiacetus begins on October 11th, 1925 when paleontologist C. Wythe Cooke collected six largish whale lumbar vertebrae from a limestone outcrop in Crisp County along the eastern bank of the Flint River, about 100 yards south of where Cedar Creek once flowed into the Flint. This is roughly nine miles west-southwest of Cordele, Georgia. (1,pg.256)

The locality is now submerged beneath Lake Blackshear. A dam was constructed on the Flint River from 1925 to 1930 to create the reservoir. Clearly, Cooke collected the fossils before or as construction was getting started. That was well done, the site is lost to us now. No doubt Cooke was aware of J.E. Brantley’s 1916 report on fossiliferous limestones in the area soon to be flooded.

At the time, Cooke identified the limestone as upper Jacksonian Ocala Limestone. Though the name Ocala limestone is still commonly used in the area, it likely isn’t accurate. We’ll look at this in the coming passages.

The fossils ended up in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collection as specimen #11401, and the fossils are still there.

At the time, Cooke identified the limestone as upper Jacksonian Ocala Limestone. Though the name Ocala limestone is still commonly used in the area, it likely isn’t accurate. We’ll look at this in the coming passages.

The fossils ended up in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collection as specimen #11401, and the fossils are still there.

Remington Kellogg reviewed and discussed Cooke’s fossils on page 256 of his very influential 1936 research report A Review of the Archeoceti. (1) Because of their relatively short length, Kellogg tentatively identified the vertebrae as belonging to Pontogeneus brachyspondylus, which was correct at the time. Species are often reassigned after being named and described. However, this wasn’t the original identification of the species. We’ll also look at this in the coming passages.

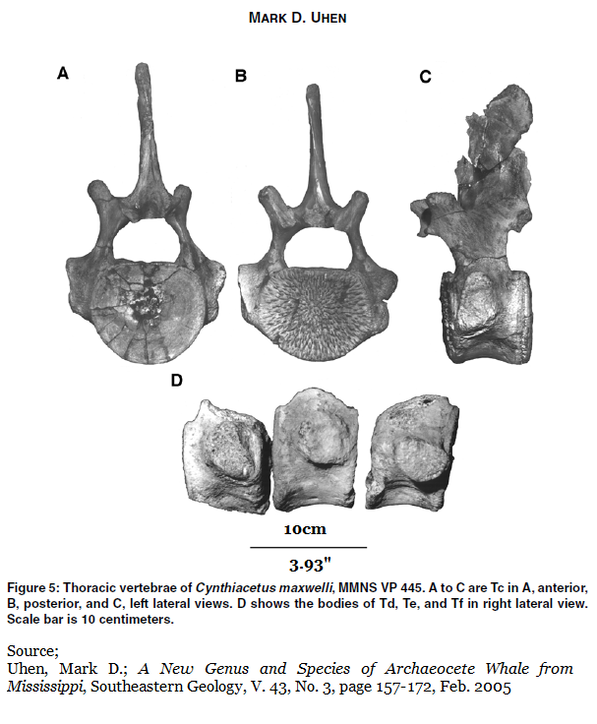

In 2005 Mark D. Uhen reassigned Pontogeneus brachyspondylus as Cynthiacetus maxwelli. This reassignment was both correct and necessary. (2)

In 2005 Mark D. Uhen reassigned Pontogeneus brachyspondylus as Cynthiacetus maxwelli. This reassignment was both correct and necessary. (2)

Together with the larger Houston County Basilosaurus cetoides, this makes two species of whales, from Georgia, reported in Kellogg’s 1936 paper which is the foundation stone for understanding the earliest true whales. (See Section 12F of this website for more on the Houston County whale.)

Wythe Cooke went on to become a prominent paleontologist and would author the essential 1959 report Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States published by the USGS, (4) which created the framework for using sand dollars and sea urchins as index fossils to date sediments. It is a reference report which is still widely used though in need of updating. It can be found online for free downloads. I have an original printed copy given to me by Paul Huddlestun. Several echinoid species, rock formations and sediments have been reassigned since publication so a update is needed.

Cooke knew he’d found unusual whale vertebrae when he collected them. This was a marine deposit, created beneath the warm sea which covered the area 34 million years ago. There were sand dollar fossils in the matrix which gave evidence to the sediments age. The fossilized bones were large and mammalian but they weren’t the elongated, mailbox sized vertebrae of the 15 to 20 meter (49-66 foot) long Basilosaurus cetoides well known from the Southeast.

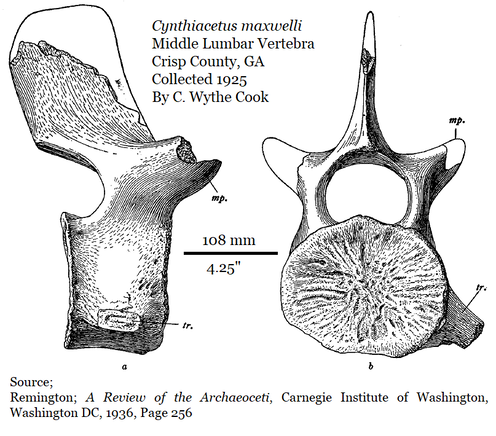

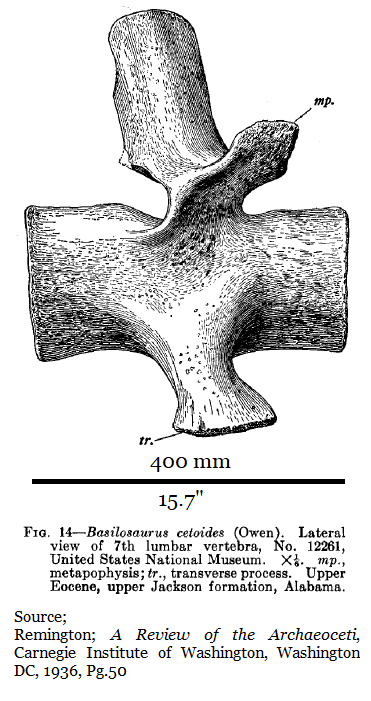

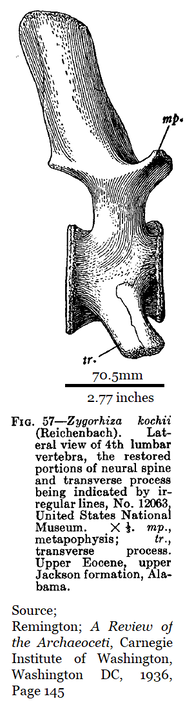

A lumber vertebra from a Basilosaurus would run 400mm (15”) in length. These were dramatically shorter at 108mm (4.25”) in length, but still robust and round in cross-section at the backbone. While they were too short to be from a Basilosaurus, they were too long to be from a Zygorhiza or Durodon the smaller 5.5 meter (18 foot) whales also known from those waters and that timeframe. Zygorhiza & Dorudon lumbar vertebra ran about 70mm (2.77”).

Clearly these vertebrae were from an archaic whale, from a large animal. Most curious.

Like today, large whales swam and hunted the coastal sea of Georgia 40 to 34 million years ago. However, sea levels were much higher then and the Southeastern Sea covered Georgia’s These fossils were found 165 miles inland from the modern coastline.

Like today, large whales swam and hunted the coastal sea of Georgia 40 to 34 million years ago. However, sea levels were much higher then and the Southeastern Sea covered Georgia’s These fossils were found 165 miles inland from the modern coastline.

Houston County Report

The Paleobiology Database lists two Georgia occurrences of Cynthiacetus maxwelli, one in Crisp County, which we've discussed, and another in Houston County. The reference for the Houston County specimen is reported in the same 1982 Smithsonian Eocene Sea Cow paper (5) which reports Georgia’s first entelodont. (For details on the entelodont see Section 16 of this website.)

The Paleobiology Database lists two Georgia occurrences of Cynthiacetus maxwelli, one in Crisp County, which we've discussed, and another in Houston County. The reference for the Houston County specimen is reported in the same 1982 Smithsonian Eocene Sea Cow paper (5) which reports Georgia’s first entelodont. (For details on the entelodont see Section 16 of this website.)

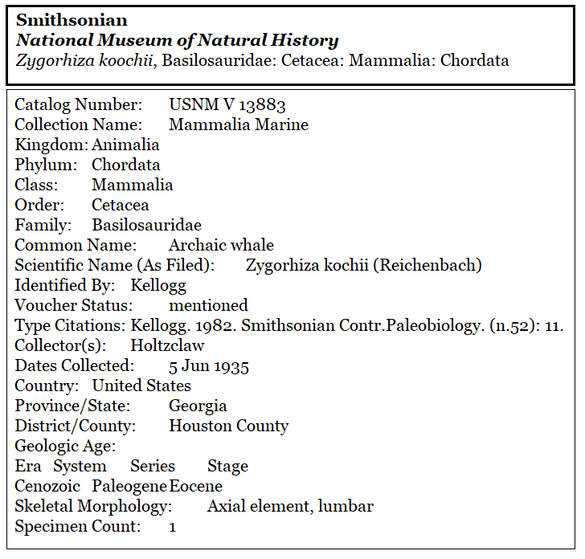

My reading of that paper does not produce a Cynthiacetus candidate. Page 11 reports a single Zygorhiza kochii lumbar vertebra (Specimen# 13883) which the Smithsonian received in 1935 from the Pennsylvania-Dixie Cement Corporation at Clinchfield, GA (now Cemex) which Kellogg personally identified.

The authors of the sea cow paper (Doming, Morgan & Clayton) describe a tray in the Smithsonian collection holding the Zygorhiza vertebra specimen #13883. “In the tray with the cetacean vertebra was an uncataloged fragment of a sirenian rib.” The researchers were looking for sea cow (siren) specimens, not whale or cetacean vertebra. The sea cow paper continues; “Examination of the registrar’s records reveals that there were several fragments of sirenian ribs (identified by Kellogg) in the collection from Clinchfield at the time of receipt.” In this context “Clinchfield” is undoubtedly referring to the locality, the town, not the formation. The Clinchfield Sand Formation was not named until 1965 when the name was proposed by Robert C. Vorhis. (6,Pg.7)

After mentioning specimen# 13883, the paper’s next paragraph begins; “Also in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution…” and the authors discuss other siren (sea cow) specimens held in the Smithsonian from the Clinchfield Georgia plant. As a cement plant Pennsylvania-Dixie was working the Tivola Limestone (known as the Ocala Limestone at the time). Beneath the Tivola Limestone is the vertebrate fossil rich Clinchfield Sand Formation.

In 1970 Sam Pickering reported Sea Cow (sirenian) ribs reported as common in the Clinchfield Sand Formation but rare in the Tivola Limestone (6,Pg.20).

The paragraph mentions a “detailed geologic section extracted from a 30/July/1945 letter from Philip E. LaMoreaux”. The paragraph explains that the other Houston County fossils came from a limy sand bed 80 feet below ground level. This would be well below the Tivola Limestone and likely in the Clinchfield Sand Formation. The Tivola Limestine is about 50 feet thick in the Cemex mines. (7,Pg.24) However, from how I read the paragraph and the dates assigned, these are separate specimens were likely collected 10 years after the 1935 Zygorhiza vertebra #13883.

The paragraph mentions a “detailed geologic section extracted from a 30/July/1945 letter from Philip E. LaMoreaux”. The paragraph explains that the other Houston County fossils came from a limy sand bed 80 feet below ground level. This would be well below the Tivola Limestone and likely in the Clinchfield Sand Formation. The Tivola Limestine is about 50 feet thick in the Cemex mines. (7,Pg.24) However, from how I read the paragraph and the dates assigned, these are separate specimens were likely collected 10 years after the 1935 Zygorhiza vertebra #13883.

Looking at the Smithsonian online database, Paleobiology Collections Search (si.edu), vertebrate Specimen #13883 was collected by Holtzclaw on 05/June/1935 from Houston County and identified by Kellogg. The record makes no mention of Pennsylvania-Dixie Cement Corporation, Clinchfield, Georgia or the Clinchfield Sand Formation.

Uhen lists this same vertebra as a Cynthiacetus maxwelli in the Referred Specimen section of his 2005 paper; “USNM 13883, one lumbar vertebra. Probably from the Clinchfield Sand Formation (Domning et al., 1982), Houston County, Georgia.” Thus, Uhen reassigned the Smithsonian Specimen V13883 from Zygorhiza to Cynthiacetus (2,pg.160).

No image or specimen measurements are given in Uhen’s 2005, Uhen’s 2013 paper, the sea cow paper, or in the official Smithsonian record.

As of 21/Feb/2021, the Smithsonian still officially lists the Houston County specimen #13883 as Zygorhiza kochii.

No image or specimen measurements are given in Uhen’s 2005, Uhen’s 2013 paper, the sea cow paper, or in the official Smithsonian record.

As of 21/Feb/2021, the Smithsonian still officially lists the Houston County specimen #13883 as Zygorhiza kochii.

In Kellogg’s 1936 description of Zygorhiza kochii he measures the specie’s lumbar vertebrae length (front to rear) to be in the 70mm (2.75”) range. He did not use the Georgia specimen #13883, he reported on the associated vertebrae from a separate, fairly complete individual in the Smithsonian collection. A similar vertebra from Cynthiacetus comes in at the 108mm (4.25”) range.

It is very difficult to imagine Kellogg confusing a Zygorhiza lumbar vertebra (2.75” long) for a much larger Cynthiacetus vertebra (4.25” long). For these reasons, I personally don’t consider the Houston County Specimen# 13883 in the Smithsonian to be a valid Cynthiacetus until some dimensions or scaled images of this specific vertebra are published.

Of course, Kellogg knew Cynthiacetus as Zeuglodon brachyspondylus. That’s the next Gordian knot in the Cynthiacetus saga.

Of course, Kellogg knew Cynthiacetus as Zeuglodon brachyspondylus. That’s the next Gordian knot in the Cynthiacetus saga.

Why was the species reassigned?

Out of one rabbit hole and into another…

Mark Uhen’s 2005 paper explains that in 1852 Joseph Leidy established a new species of archaic whale named Pontogeneus priscus based this on a single cervical vertebra from Louisiana. This vertebra has since been lost. (3,Pg.10)

Out of one rabbit hole and into another…

Mark Uhen’s 2005 paper explains that in 1852 Joseph Leidy established a new species of archaic whale named Pontogeneus priscus based this on a single cervical vertebra from Louisiana. This vertebra has since been lost. (3,Pg.10)

In 1845 Albert Koch went to Alabama and collected enough material from several localities to assemble a 114-foot skeleton meant as a scientific deception and a traveling public display. There was a time when Eocene whale fossils were abundant in parts of Alabama. He presented the assemblage as an actual sea monster named Hydrarchos harlani. Koch’s creation was intended as a profitable venture, there was no science involved. His creation went on a national tour, then a European tour.

His fake included the remains of several basilosaurids as well as the shorter vertebra later attributed to Cynthiacetus, but these were unknown to science at the time.

His fake included the remains of several basilosaurids as well as the shorter vertebra later attributed to Cynthiacetus, but these were unknown to science at the time.

Koch sold the 114ft skeleton to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, it was later destroyed during WWII. Koch then returned to Alabama and assembled a second 96ft Hydrarchos harlani which he took on a US tour. He sold the second one to a Chicago curiosity museum and in 1871 it was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire.

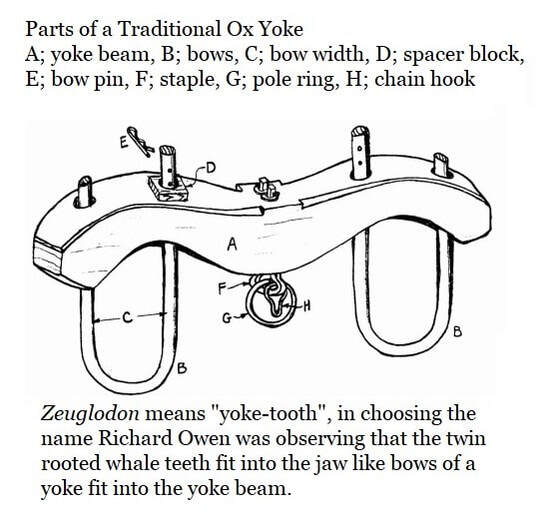

Koch did not fool the paleontologists. In 1849 paleontologist J. Müller noticed the shortened, large vertebrae in the first Hydrarchos harlani and published a paper naming a new species Zeuglodon brachyspondylus based on the shortened vertebrae.

Koch did not fool the paleontologists. In 1849 paleontologist J. Müller noticed the shortened, large vertebrae in the first Hydrarchos harlani and published a paper naming a new species Zeuglodon brachyspondylus based on the shortened vertebrae.

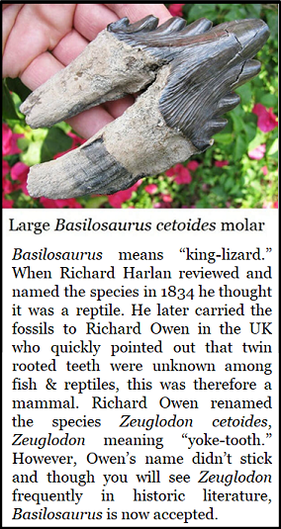

Zeuglodon means “yoke tooth” which is actually a more accurate name for Basilosaurus, which means “king lizard”. In 1834 Richard Harlan coined the name Basilosaurus cetoides when he first described the beast which possessed such “enormous” long vertebrae. These were fossils recovered from two individuals discovered in Louisiana. The sheer size convinced Harlan that they belonged to a giant reptile, never mind the twin rooted teeth.

In 1839 Harlan carried his fossils to the UK where the famous anatomist Richard Owen reviewed them. Owen quickly noticed the twin rooted molars and pointed out that this feature was unknown to either fish or reptiles and therefore must represent a more advanced mammal, an enormous mammal. Harlan, upon review, agreed. Richard Owen coined the name Zeuglodon cetoides.

In 1839 Harlan carried his fossils to the UK where the famous anatomist Richard Owen reviewed them. Owen quickly noticed the twin rooted molars and pointed out that this feature was unknown to either fish or reptiles and therefore must represent a more advanced mammal, an enormous mammal. Harlan, upon review, agreed. Richard Owen coined the name Zeuglodon cetoides.

In 1936 Remington Kellogg faced this morass, while reviewing Wythe Cook’s six vertebrae from Crisp County, among others, and opted to split the difference and placed them as Zeuglodon brachspondylus after Müller, but no holotype was assigned for later diagnostic comparison.

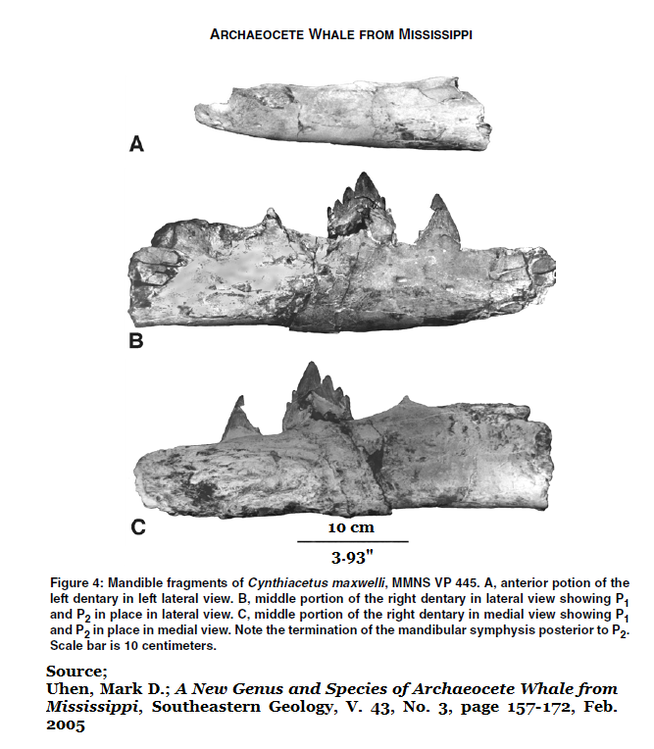

In 1988 Britt Maxwell discovered associated whale fossils in the mining pits of the Yazoo Clay Formation of Cynthia, Mississippi in Hinds County. In May of that year Elanor Daly professionally excavated the fossils. The remains included a relatively complete skull, jaws; teeth, cervical vertebrae, thoracic vertebrae, lumbar vertebrae, ribs, sternum, and forelimb elements. (2)

With no holotype erected for diagnostic comparison, Uhen considered both Zeuglodon brachyspondylus and Pontogeneus priscus as invalid or nomen nudum. In 2005 Uhen established the species Cynthiacetus maxwelli from the Cynthia Clay Pit specimen discovered by Britt Maxwell. (2)

However both Uhen’s 2005 & 2013 papers give long lists of institutions where the various diagnostic skeletal elements are housed (2,3) but several fossils are held by the Florida Museum of Natural History and the Florida Geologic Survey Collection.

Age of the Limestone Deposits in Crisp County, Georgia.

Okay, so we’ve climbed out that rabbit hole. Now take a deep breath because here we go again, plunging down the last rabbit hole.

Okay, so we’ve climbed out that rabbit hole. Now take a deep breath because here we go again, plunging down the last rabbit hole.

Back to the beginning… In 1925 Wythe Cooke reported that he’d collected six vertebrae from the Ocala Limestone of the upper Jackson Formation in Crisp County along the Flint River. This would be the late Eocene epoch. The name Jackson Formation is long abandoned. The Ocala Limestone is simply incorrect with today’s understanding. However, both of these issues are problematical.

Paul Huddlestun, who is now in his 80s and lives in New Mexico, explained in a recent email & phone conversation (17/Feb/2021) that he’s seen the formation Cooke collected the vertebra from and reports that its unnamed and hasn’t been described in the literature for more than a century. But I get ahead of myself.

Today the Jackson, or Jacksonian Stage, isn’t a formation but a regional measure of time applicable to Southeastern (regional) sediments. It's named for Jackson, Mississippi which is also in Hinds County. It represents an event, an observable change in the sediments. It took years to precisely date the event, so for decades the published dates wandered a bit.

In general, the Jacksonian Stage represents a shift in species populations and conditions within Southeastern sediments.

In general, the Jacksonian Stage represents a shift in species populations and conditions within Southeastern sediments.

Paul Huddlestun is a PhD invertebrate paleontologist specializing in foraminifera (forams) or “bugs’ as Mr. Paul often calls them. As lead author of the papers defining much of Georgia’s Eocene sediments it’s no surprise that he used forams to date and define sediments. Forams are useful towards that end. (For more info on dating sediments with forams see Section 14I of this website.)

In 1986 Huddlestun and Hetrick reported that where present, the base of the Jacksonian is easily defined by the planktonic foraminifera as these species sporadically occur in strata beneath Jacksonian Stage deposits but are totally absent in the overlying Jacksonian strata. (7,pg13)

Truncorotaloides topilensis

Truncorotaloides rohri

Globorotalia (Morozovella) spinulosa

Truncorotaloides topilensis

Truncorotaloides rohri

Globorotalia (Morozovella) spinulosa

At the same time the authors further divide the Jacksonian Stage into early and late stages to increase the accuracy of dating. A natural division occurs as a localized uplift event (epeirogenic uplift) along the continental shelf which created an observable shift in sea levels and specie populations. The divide is “…separated by a “marker zone” or discontinuity that generally is a conspicuous contact in the field (Huddlestun & Hetrick, 1978).” The authors explain that the contact can be traced from eastern Mississippi to central South Carolina. (7,Pg.12)

Lower Jacksonian foraminifera

Globigerinatheka semiinvoluta

Globigerinatheka tropicalis

Globigerina linaperta

Turborotalia cerroazulensis cerroazulensis

(Formerly Globorotalia cerroazulensis cerroazulensis) (7)

Upper Jacksonian Foraminifera

Cribrohantkenina inflata

(absent in most lower Jacksonian facies)

Turborotalia cerroazulensis cocoaensis

(Formerly Globorotalia cerroazulensis cocoaensis) (7)

Lower Jacksonian foraminifera

Globigerinatheka semiinvoluta

Globigerinatheka tropicalis

Globigerina linaperta

Turborotalia cerroazulensis cerroazulensis

(Formerly Globorotalia cerroazulensis cerroazulensis) (7)

Upper Jacksonian Foraminifera

Cribrohantkenina inflata

(absent in most lower Jacksonian facies)

Turborotalia cerroazulensis cocoaensis

(Formerly Globorotalia cerroazulensis cocoaensis) (7)

The most recent dating of the Jacksonian from Paleodata (8) places it from 33.9 to 36.8 million years ago. 33.9 Million years ago is the upper limit since that is when the Eocene ended with global glaciation and extinction event after millions of years of a hothouse, probably ice free, Earth. The Jacksonian uplift occurred at approximately 35.2 million years ago.

Roughly speaking…

Late Jacksonian spans from 33.9 to 35.2 million years ago.

Early Jacksonian spans from 35.2 to 36.8 million years ago.

Roughly speaking…

Late Jacksonian spans from 33.9 to 35.2 million years ago.

Early Jacksonian spans from 35.2 to 36.8 million years ago.

The Ocala Limestone, Kellogg and Cooke report that the fossils came from the upper Jackson Formation means that they are between 33.9 to 35.2 million years old. They also refer to the sediments as the Ocala Limestone. The Ocala Limestone was named in 1892 by Dall and Harris and can be found in much of Florida. (11,Pg.23)

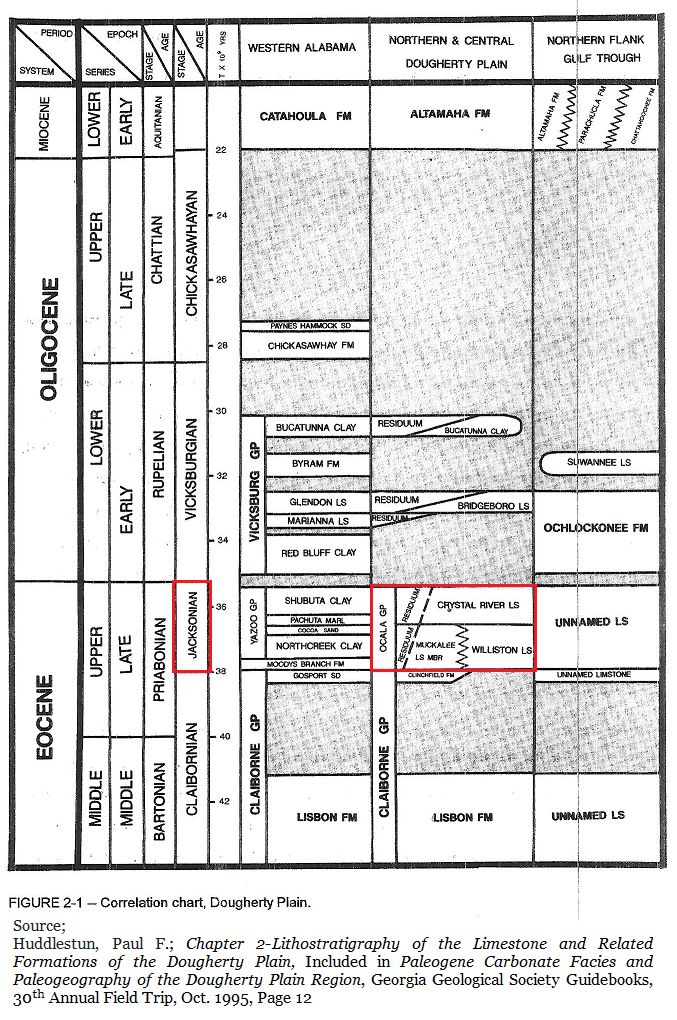

Many researchers generally refer to southwest Georgia’s Late Eocene limestones as Ocala Limestones. Through the years researchers in Georgia and Florida have additionally recognized that the Ocala Limestones divides into an upper & lower element. However, in Paul Huddlestun’s 1981 Correlation Chart Georgia Coastal Plain (14) we see that he has already replaced the Ocala Limestone with the Ocala Group and includes many Georgia limestones of similar ages. He also reassigned the upper and lower Ocala limestone as the upper Crystal River Formation and a lower Williston Formation.

In 1986 Huddlestun & Hetrick’s further described Georgia’s Ocala Group of sediments as covering the full expanse of the Jacksonian Stage, ending at the Eocene/Ologicene horizon at 33.9 million years ago. But Huddlestun and Hetrick didn’t really define either the Crystal River or the Williston more fully. (7,pg.50) Of course, Burt Carter is the Southwest Georgia expert, and he corrected this issue in 1995.

Therefore, if our Cynthiacetus maxwelli hunted a Latest Eocene sea we are going to have to be more precise in dating the sediments than referring to them as the Ocala Group or Ocala Limestone.

(In 1991 Thomas M. Scott downgraded the Ocala Group back to the Ocala Limestone in a Florida Geologic Survey paper entitled; A Geologic Overview of Florida (11). For our purposes in this article we’re going to keep Huddlestun’s definition of the Ocala Group as applied to Georgia.)

(In 1991 Thomas M. Scott downgraded the Ocala Group back to the Ocala Limestone in a Florida Geologic Survey paper entitled; A Geologic Overview of Florida (11). For our purposes in this article we’re going to keep Huddlestun’s definition of the Ocala Group as applied to Georgia.)

In 1995 Burt Carter, PhD at Georgia Southwestern led the Georgia Geological Society on their 30th annual field trip across parts of Southwest Georgia’s Dougherty Plain (9). Together, Carter & Huddlestun described and dated the Crystal River and Williston Limestones.

Huddlestun authored Chapter 2 of Burt’s 1995 Field Trip (9,Pg.11) There he described both the Crystal River & Williston Limestones.

The Crystal River Limestone

The Crystal River limestone correlates with the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation which occur further north. All three are uppermost (latest) Eocene. Recent conversations with both Burt Carter and Paul Huddlestun confirm that they both still hold this opinion in 2021. The Crystal River is restricted to the region south of the vicinity of the Gulf Trough and Altamaha River and possessing known dolomite and dolostone occurrences. Other than traces of glauconite, sand and clay, no other lithic components are known to occur. There are five basic variants of the Crystal River limestone.

Exposures of the Crystal River limestone along Lake Blackshear in Crisp County and at Muckafoonee Creek in Albany are not typical. At these sites the Crystal River consists of macro-fossiliferous limestone rich in neither large foraminifera or mollusks. (9,Pg.17-18)

The Crystal River limestone correlates with the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation which occur further north. All three are uppermost (latest) Eocene. Recent conversations with both Burt Carter and Paul Huddlestun confirm that they both still hold this opinion in 2021. The Crystal River is restricted to the region south of the vicinity of the Gulf Trough and Altamaha River and possessing known dolomite and dolostone occurrences. Other than traces of glauconite, sand and clay, no other lithic components are known to occur. There are five basic variants of the Crystal River limestone.

- A coquina dominated by large Lepidocyclina forams.

- A molluscan-rich limestone.

- A miliolid-rich (foram) limestone

- A chalky, fine to medium textured, massive bedded, finely bioclastic limestone.

- A bryozoan coquina limestone.

Exposures of the Crystal River limestone along Lake Blackshear in Crisp County and at Muckafoonee Creek in Albany are not typical. At these sites the Crystal River consists of macro-fossiliferous limestone rich in neither large foraminifera or mollusks. (9,Pg.17-18)

Williston Limestone

The Williston Limestone is subsurface in Georgia, there are no known exposures in our state. It is characteristically consisted of granular, fairly even textured, moderately to well-sorted, fine to coarse grained, chalky to well washed and clean, sparingly to non-macro-fossiliferous calcarenite that locally may contain abundantly macro-fossiliferous beds or lenses. (9,Pg.13)

The Williston Limestone is subsurface in Georgia, there are no known exposures in our state. It is characteristically consisted of granular, fairly even textured, moderately to well-sorted, fine to coarse grained, chalky to well washed and clean, sparingly to non-macro-fossiliferous calcarenite that locally may contain abundantly macro-fossiliferous beds or lenses. (9,Pg.13)

However, Mr. Paul reports that the exposure Cooke collected his six vertebrae from was yet another unnamed limestone. Also, the Southwest Georgia Ocala Limestone issue remains unresolved and is sorely in need of more research.

In a 17/Feb/2021 email Huddlestun explains… I asked Mr. Paul what he knew of the limestone 100 yards south of where Cedar Creek flowed into the Flint River.

In a 17/Feb/2021 email Huddlestun explains… I asked Mr. Paul what he knew of the limestone 100 yards south of where Cedar Creek flowed into the Flint River.

Wed, Feb 17, 2021 2:55 pm

Thomas:

I know the exposures you are referring to. Back in the early, middle 70’s they were working on the dam down river and they lowered the water level in Lake Blackshear. Bill Marsalis, the head of the Coastal Plain unit of the time, got us out there in a boat and we examined those exposures. I was still pretty low on the learning curve at the time, but I had seen enough Crystal River Limestone to be impressed.

Whatever the limestone was, it wasn’t Crystal River lithology, nor Ocmulgee. We found what was apparently lower Ocala near the US 280 bridge but that was not what was exposed downstream. It was full of fossils but not sub-coquinoid. As I remember, there were plenty of echinoids, but they were cemented into the outcrop and could be recovered only with difficulty. The one thing that impressed me about the lithology is that it was not Lepidocyclina-rich limestone, let alone a Lepidocyclina coquina to sub-coquina that is typical for the Crystal River.

As a result, I couldn’t call it Crystal River; the Crystal River is also full of various kinds of other, fossils, biofragments and other bio-debris. The lime matrix was mostly granular, kind of like the Ocmulgee matrix. But it’s not Crystal River; it’s much more like the Upper Ocala that’s exposed at Albany.

So here are my thoughts on the Upper Eocene, Ocala Group limestones along the Flint River. They need another formation name. I never had time to work on the upper Eocene in that neighborhood and its unfinished business.

The Flint River Ocala appears to be a lithofacies intermediate between the Ocmulgee and the Crystal River. If so, then farther east in the central Coastal Plain, the Flint River, Upper Jackson should/could be present between the Gulf Trough to the south and the Hawkinsville area in the north. Our southernmost core was taken near the lookout tower south of Hawkinsville and good Ocmulgee is present in that core. I would have liked to have gotten a core from 10 to 15 miles south of Hawkinsville but, I never was okayed for any cores after Sam left; which has left a number of holes in my knowledge of critical areas in the Coastal Plain.

Paul

Thomas:

I know the exposures you are referring to. Back in the early, middle 70’s they were working on the dam down river and they lowered the water level in Lake Blackshear. Bill Marsalis, the head of the Coastal Plain unit of the time, got us out there in a boat and we examined those exposures. I was still pretty low on the learning curve at the time, but I had seen enough Crystal River Limestone to be impressed.

Whatever the limestone was, it wasn’t Crystal River lithology, nor Ocmulgee. We found what was apparently lower Ocala near the US 280 bridge but that was not what was exposed downstream. It was full of fossils but not sub-coquinoid. As I remember, there were plenty of echinoids, but they were cemented into the outcrop and could be recovered only with difficulty. The one thing that impressed me about the lithology is that it was not Lepidocyclina-rich limestone, let alone a Lepidocyclina coquina to sub-coquina that is typical for the Crystal River.

As a result, I couldn’t call it Crystal River; the Crystal River is also full of various kinds of other, fossils, biofragments and other bio-debris. The lime matrix was mostly granular, kind of like the Ocmulgee matrix. But it’s not Crystal River; it’s much more like the Upper Ocala that’s exposed at Albany.

So here are my thoughts on the Upper Eocene, Ocala Group limestones along the Flint River. They need another formation name. I never had time to work on the upper Eocene in that neighborhood and its unfinished business.

The Flint River Ocala appears to be a lithofacies intermediate between the Ocmulgee and the Crystal River. If so, then farther east in the central Coastal Plain, the Flint River, Upper Jackson should/could be present between the Gulf Trough to the south and the Hawkinsville area in the north. Our southernmost core was taken near the lookout tower south of Hawkinsville and good Ocmulgee is present in that core. I would have liked to have gotten a core from 10 to 15 miles south of Hawkinsville but, I never was okayed for any cores after Sam left; which has left a number of holes in my knowledge of critical areas in the Coastal Plain.

Paul

I shared this email with Burt Carter, and he replied; 18/Feb/2021

Thomas

We’re talking about the same rocks for sure. How they relate to the rocks at Albany is not clear to me, and how the rocks at the dam in north Albany relate to the ones south of town is also not clear, but the rocks south of Albany are not upper Ocala, they are Oligopygus haldemani zone rocks, from the south edge of town all the way south. This argues that the rocks at the dam are also middle Ocala, like Paul says when he puts them equivalent to the Williston.

Burt

Thomas

We’re talking about the same rocks for sure. How they relate to the rocks at Albany is not clear to me, and how the rocks at the dam in north Albany relate to the ones south of town is also not clear, but the rocks south of Albany are not upper Ocala, they are Oligopygus haldemani zone rocks, from the south edge of town all the way south. This argues that the rocks at the dam are also middle Ocala, like Paul says when he puts them equivalent to the Williston.

Burt

1917 Report

As a final twist, in 1917 J.E. Brantly visited and wrote a report on the limestones exposed where Cedar Creek flowed into the Flint River. It was, no doubt, this report which led Wythe Cooke to visit the “soon to be submerged” site in 1925.

Brantly was conducting a specific survey of limestones & marls, with an eye towards their economic value, in the wake of more general field research published in 1911 by Otto Veatch & Lloyd William Stephenson. (13) Brantly reported “An excellent exposure of limestone occurs 100 yards down-stream from the mouth of Cedar Creek in a river bluff…” (10,Pg.161) He went on to describe a 39 foot exposure topped with sands. He only recorded a single fossil, the nearly circular bivalve, Amusium ocalanum which is common and often numerous in Florida’s Ocala Limestone and thus, no doubt, led the researchers to refer to this limestone as Ocala. Brantly does not name the limestone, he reported many limestones which he never named. But he does give us a section description.

As a final twist, in 1917 J.E. Brantly visited and wrote a report on the limestones exposed where Cedar Creek flowed into the Flint River. It was, no doubt, this report which led Wythe Cooke to visit the “soon to be submerged” site in 1925.

Brantly was conducting a specific survey of limestones & marls, with an eye towards their economic value, in the wake of more general field research published in 1911 by Otto Veatch & Lloyd William Stephenson. (13) Brantly reported “An excellent exposure of limestone occurs 100 yards down-stream from the mouth of Cedar Creek in a river bluff…” (10,Pg.161) He went on to describe a 39 foot exposure topped with sands. He only recorded a single fossil, the nearly circular bivalve, Amusium ocalanum which is common and often numerous in Florida’s Ocala Limestone and thus, no doubt, led the researchers to refer to this limestone as Ocala. Brantly does not name the limestone, he reported many limestones which he never named. But he does give us a section description.

Section of Limestone Bluff 100 Yards below the Mouth of Cedar Creek, Flint River (10,Pg161)

8. Unconsolidated sands of probable Pleistocene age;

second terrace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 ft

7. Hard, white, partly crystalline limestone.. . . . . 1 ft

6. Soft, white, granular limestone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.3ft

5. Hard, cream colored, partly crystalline limestone. . . 0.9ft

4. Soft, white, granular limestone. . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . 3ft

3. Medium soft, white limestone; Amusium ocalanum ( ?) 1ft

2. Soft, white, granular, argillaceous limestone. . . . . . . 8ft

1. Hard, white, crystalline limestone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4ft

River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0

8. Unconsolidated sands of probable Pleistocene age;

second terrace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 ft

7. Hard, white, partly crystalline limestone.. . . . . 1 ft

6. Soft, white, granular limestone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.3ft

5. Hard, cream colored, partly crystalline limestone. . . 0.9ft

4. Soft, white, granular limestone. . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . 3ft

3. Medium soft, white limestone; Amusium ocalanum ( ?) 1ft

2. Soft, white, granular, argillaceous limestone. . . . . . . 8ft

1. Hard, white, crystalline limestone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4ft

River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0

The limestone could have certainly been useful for agricultural purposes, but the 18 feet of sand topping it made it unprofitable, at the time, for quarrying operations. Brantly reported that the creek had cut through and flowed across the limestone for a quarter mile upstream from the river and was frequently within a foot or two of the creek’s surface. That this could be accessed relatively easily for local agricultural usage.

That was more than a century ago.

That was more than a century ago.

In 2005 Mark D. Uhen established Cynthiacetus maxwelli as a new genus and species of whale and the vertebrae Wythe Cooke collected from Crisp County, helped make that happen. The animal lived 34 million years ago, right at the end of the Eocene. It was collected just a few miles west of Cordele, Georgia nearly a century ago and the fossils are safely stored in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

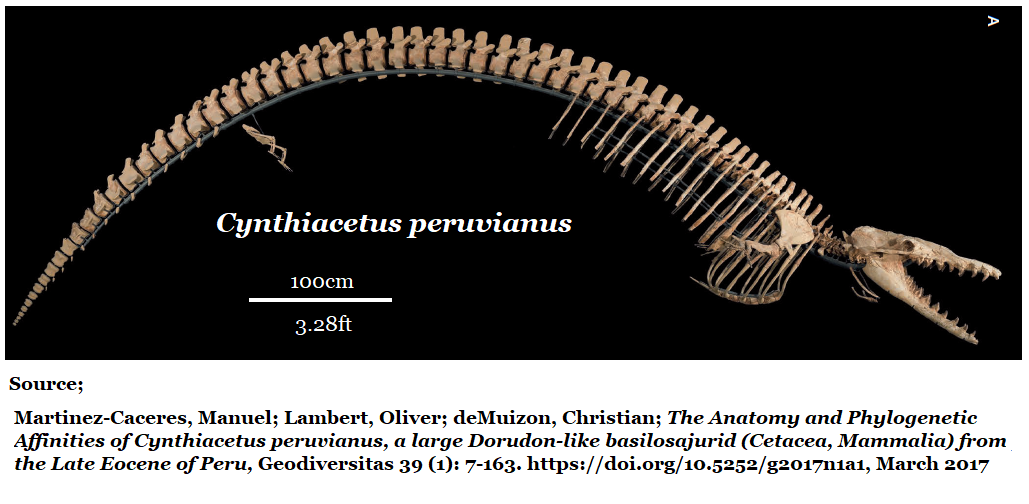

In 2011 Martínez-Cáceres & Muizon reported another new species of Cynthiacetus occurring in Peru, Cynthiacetus peruvianus, (imaged at the top of this piece) which is described as a larger Dorudon-like member of the basilosaurid family. A second species would tend to stabilize the genus.

Thus we emerge at last from the warren of rabbit burrows which is Georgia’s natural history around Cynthiacetus.

Ah… the joys of history.

In 2011 Martínez-Cáceres & Muizon reported another new species of Cynthiacetus occurring in Peru, Cynthiacetus peruvianus, (imaged at the top of this piece) which is described as a larger Dorudon-like member of the basilosaurid family. A second species would tend to stabilize the genus.

Thus we emerge at last from the warren of rabbit burrows which is Georgia’s natural history around Cynthiacetus.

Ah… the joys of history.

References

- Kellogg, Remington; A Review of the Archaeoceti, Carnegie Institute of Washington, Washington DC, 1936

- Uhen, Mark D.; A New Genus and Species of Archaeocete Whale from Mississippi, Southeastern Geology, V. 43, No. 3, page 157-172, Feb. 2005

- Uhen, Mark D.; A Review Of North American Basilosauridae, Contributions to Alabama Paleontology, Alabama Museum of Natural History, Bulletin 31, Vol.1, April 1, 2013

- Cooke, C. Wythe; Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States, USGS Geological Survey Professional Paper 321, 1959

- Domning, Daryl P.; Morgan, Gary S.; Clayton, E. Ray; North American Eocene Sea Cows (Mammalia: Sirenia) Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, #52, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982

- Pickering, S. M. Jr; Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 81, 1970

- Huddlestun, Paul F.; Hetrick, John H.; Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central & Eastern Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 95, 1986.

- Paleo-Data; PDI Paleogene Biostratigraphic Chart – Gulf Basin, USA. Updated March 2o17; https://www.paleodata.com/chart/

- Carter, Burchard D; Paleogene Carbonate Facies and Paleogeography of the Dougherty Plain Region, Georgia Geological Society Guidebooks, 30th Annual Field Trip, Oct. 1995.

- Brantly, J.E.; Assistant State Geologist; A Report on the Limestones and Marls of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, Geological Survey of Georgia, Bulletin #21, 1916

- Scott, T.M, Lloyd, J.M, and Maddox, G., A Geological overview of Florida: Florida's Ground Water Quality Monitoring Program- Hydrogeological Framework: Florida Geological Survey Special Publication 32, p. 5-14.

- Huddlestun, Paul F.; Chapter 2-Lithostratigraphy of the Limestone and Related Formations of the Dougherty Plain, Included in Paleogene Carbonate Facies and Paleogeography of the Dougherty Plain Region, Georgia Geological Society Guidebooks, 30th Annual Field Trip, Oct. 1995.

- Veatch, Otto; Stephenson, Lloyd, William; Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 26, 1911

- Huddlestun, Paul F; Correlation Chart, Georgia Coastal Plain, Open File Report 82-1, Georgia Geological Survey, 1981