|

|

|

4; Georgia's Oldest Vertebrate?

450 million years ago

Genus; Astraspis

By Thomas Thurman

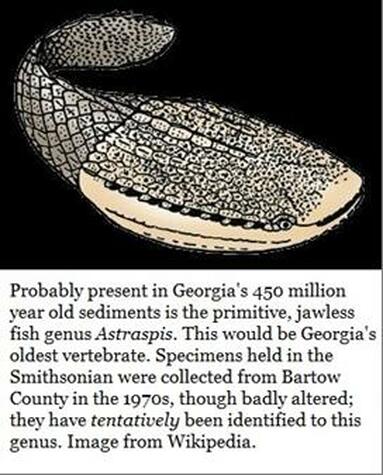

Georgia’s oldest vertebrate fossil might be a small, armored, jawless, primitive fish of the superclass agnatha and the genus Astraspis.

The online catalog for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History reports six dermal bones, perhaps from an Astraspis, in their collection as specimen number PAL 327037. These were collected in Northwest Georgia’s Bartow County during the 1970s from a road cut two miles north of Taylorsville.

Astraspis is a primitive eight inch fish which looked something like a tadpole but lived during the Ordovician Period (443.7 to 488.3 million years ago) long before frogs or tadpoles emerged. It was a jawless fish well known from Colorado, Arizona, Oklahoma, Wyoming and Canada. It lived before evolution had produced the mandible, or lower jaw.

When Astraspis lived sea levels were very high, higher than at any other point in Paleozoic (ancient life) times. The global climate was hot due to high levels of CO2 and a greenhouse effect. Estimates put marine surface temperatures at around 45°C (113°F). By comparison, the 20th century global marine surface temperature average is 16°C (61°F), and climbing.

These high temperatures tended to curb diversification of life but trilobites were still plentiful. Cooler global temperatures later in the Ordovician led to greater diversify and density of life.

Bones, in a primitive form, are now present on the Earth and seen as armor on fish, jawed fish are just beginning to appear. Within another 100 million years the first primitive sharks will appear.

Leaves and wood are yet to be seen on Earth, the first terrestrial plants were green algae which had emerged during the Cambrian and were still present in the Ordovician (as it is today) but by the time of Astraspis liverwort-like plants were the dominant flora on land, very near the water. Fungi were also present on land and played a role in helping plants to colonize land. Fossilize fungi spores dated to 460 million years ago are known from Wisconsin.

Earth was a different place, most of earth’s landmasses were in the Southern Hemisphere. What would become, in many millions of years, the Great Lakes of North America rested on the equator. Georgia was well into the Southern Hemisphere and completely submerged beneath the Iapetus Ocean. The landmass which would eventually become Antarctica was well to the east of Georgia, and also resting on the Equator.

The agnathans emerged during the Cambrian Period and shared Earth’s sea with trilobites; agnathans from this time frame possessed heavy armor or dermal plates, especially around their heads and lacked the paired fins of modern fish. Modern lampreys and hagfish are also agnathans; but are covered by skin and lack scales. The ancient agnathans probably had cartilage skeletons like modern sharks.

Astraspis is not previously reported in Georgia. When I ran across this entry in the Smithsonian files I contacted Thomas Jorstad; The Smithsonian’s Paleobiology Information Officer about these specimens.

I also contacted Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern State University and requested his input. Dr. Carter is a Professor of Paleontology, sedimentary geologist, invertebrate paleontologist, respected scientist and science educator with Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus, Georgia and has worked Georgia’s fossil record for more than twenty years and has field experience in sediments of this age; we’ll see more of his work later.

Dr. Carter reports encountering poor quality fossils which were possibly dermal bones from agnathans in Georgia’s Ordovician sediments, but none of this material was preserved well enough for proper identification.

Dr. Carter stated; “…nothing I’d care to try and identify to genus”. Dr. Carter speculated; “Either, these are in good shape, somebody was really good at identifying bones, or they assumed that since only (ancient) agnathans are known from the Ordovician that must be what they are.”

A few days later I was contacted by to David J. Bohaska; Vertebrate Collections Manager for the Smithsonian; Mr. Jorstad had referred my question to Mr. Bohaska:

On 17, April, 2013 Mr. Bohaska replied to my query as follows:

Mr. Thurman:

I was able to locate the specimens in the Fish Taxonomic Collection. They consist of five pieces of light tan shale with some small specks circled with ink, and a small glass vial with sand grain sized samples. I haven’t had a chance to examine the specimens with hand lens or microscope, but the attached report, by an expert on Paleozoic fish (Dick Lund), is not encouraging.

Although there are now accepted vertebrates in the Cambrian, at least through my graduate school days the oldest generally accepted vertebrates were from the Middle Ordovician Harding Sandstone and equivalent units, which I believe are all out west. (I’ve collected in the Harding in Colorado). One of the two genera in the Harding is Astraspis. If the material is actually identifiable it may be of interest beyond being the oldest (vertebrate) fossils in Georgia.

The report is a USGS “examine and report” request. It was probably done in support of a field project by Charles W. Cressler, I’ve forwarded this to John Pojeta of the USGS for comment.

Sincerely yours,

Dave Bohaska

1979 Report referred to by Mr. Bohaska;

Referred by: Charles W. Cressler

Report Prepared By: Dick Lund and Frank C. Whitmore, Jr.

Date Received; 1/Oct/1976

Date Reported; 23/Jan/1979

Status of Work; Complete

The fish fragments, on which I reported in 1976, have been re-examined by Dick Lund of Adelphi University. He reports as follows:

The Georgia samples, which are being returned by mail, are pretty grim. They are so badly altered that it is all but impossible to convince myself that they are even vertebrate. But, an occasional chip seems to indicate that the structures visible are composed of isolated odontodes. (Odontodes, or dermal teeth, are hard structures found on the external surfaces of animals or near internal openings.) This suggests an affinity with Astrispis and other Ordovician Heterostraci (Heterostraci or "Different scales" is an extinct class of jawless vertebrates that lived primarily in marine and estuary environments.), rather than with anything later. The appalling condition of the material makes this very tentative, however.

The specimens are being retained in the National Collections.

Frank C. Whitmore, Jr.

For: Dick Lund

If these specimens represent agnathans swimming in the sea which once covered Georgia, and Dr. Carter’s comments suggest that this is at least possible, then the Southeast represents an almost complete fossil record from the Cambrian Explosion to today.

The online catalog for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History reports six dermal bones, perhaps from an Astraspis, in their collection as specimen number PAL 327037. These were collected in Northwest Georgia’s Bartow County during the 1970s from a road cut two miles north of Taylorsville.

Astraspis is a primitive eight inch fish which looked something like a tadpole but lived during the Ordovician Period (443.7 to 488.3 million years ago) long before frogs or tadpoles emerged. It was a jawless fish well known from Colorado, Arizona, Oklahoma, Wyoming and Canada. It lived before evolution had produced the mandible, or lower jaw.

When Astraspis lived sea levels were very high, higher than at any other point in Paleozoic (ancient life) times. The global climate was hot due to high levels of CO2 and a greenhouse effect. Estimates put marine surface temperatures at around 45°C (113°F). By comparison, the 20th century global marine surface temperature average is 16°C (61°F), and climbing.

These high temperatures tended to curb diversification of life but trilobites were still plentiful. Cooler global temperatures later in the Ordovician led to greater diversify and density of life.

Bones, in a primitive form, are now present on the Earth and seen as armor on fish, jawed fish are just beginning to appear. Within another 100 million years the first primitive sharks will appear.

Leaves and wood are yet to be seen on Earth, the first terrestrial plants were green algae which had emerged during the Cambrian and were still present in the Ordovician (as it is today) but by the time of Astraspis liverwort-like plants were the dominant flora on land, very near the water. Fungi were also present on land and played a role in helping plants to colonize land. Fossilize fungi spores dated to 460 million years ago are known from Wisconsin.

Earth was a different place, most of earth’s landmasses were in the Southern Hemisphere. What would become, in many millions of years, the Great Lakes of North America rested on the equator. Georgia was well into the Southern Hemisphere and completely submerged beneath the Iapetus Ocean. The landmass which would eventually become Antarctica was well to the east of Georgia, and also resting on the Equator.

The agnathans emerged during the Cambrian Period and shared Earth’s sea with trilobites; agnathans from this time frame possessed heavy armor or dermal plates, especially around their heads and lacked the paired fins of modern fish. Modern lampreys and hagfish are also agnathans; but are covered by skin and lack scales. The ancient agnathans probably had cartilage skeletons like modern sharks.

Astraspis is not previously reported in Georgia. When I ran across this entry in the Smithsonian files I contacted Thomas Jorstad; The Smithsonian’s Paleobiology Information Officer about these specimens.

I also contacted Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern State University and requested his input. Dr. Carter is a Professor of Paleontology, sedimentary geologist, invertebrate paleontologist, respected scientist and science educator with Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus, Georgia and has worked Georgia’s fossil record for more than twenty years and has field experience in sediments of this age; we’ll see more of his work later.

Dr. Carter reports encountering poor quality fossils which were possibly dermal bones from agnathans in Georgia’s Ordovician sediments, but none of this material was preserved well enough for proper identification.

Dr. Carter stated; “…nothing I’d care to try and identify to genus”. Dr. Carter speculated; “Either, these are in good shape, somebody was really good at identifying bones, or they assumed that since only (ancient) agnathans are known from the Ordovician that must be what they are.”

A few days later I was contacted by to David J. Bohaska; Vertebrate Collections Manager for the Smithsonian; Mr. Jorstad had referred my question to Mr. Bohaska:

On 17, April, 2013 Mr. Bohaska replied to my query as follows:

Mr. Thurman:

I was able to locate the specimens in the Fish Taxonomic Collection. They consist of five pieces of light tan shale with some small specks circled with ink, and a small glass vial with sand grain sized samples. I haven’t had a chance to examine the specimens with hand lens or microscope, but the attached report, by an expert on Paleozoic fish (Dick Lund), is not encouraging.

Although there are now accepted vertebrates in the Cambrian, at least through my graduate school days the oldest generally accepted vertebrates were from the Middle Ordovician Harding Sandstone and equivalent units, which I believe are all out west. (I’ve collected in the Harding in Colorado). One of the two genera in the Harding is Astraspis. If the material is actually identifiable it may be of interest beyond being the oldest (vertebrate) fossils in Georgia.

The report is a USGS “examine and report” request. It was probably done in support of a field project by Charles W. Cressler, I’ve forwarded this to John Pojeta of the USGS for comment.

Sincerely yours,

Dave Bohaska

1979 Report referred to by Mr. Bohaska;

Referred by: Charles W. Cressler

Report Prepared By: Dick Lund and Frank C. Whitmore, Jr.

Date Received; 1/Oct/1976

Date Reported; 23/Jan/1979

Status of Work; Complete

The fish fragments, on which I reported in 1976, have been re-examined by Dick Lund of Adelphi University. He reports as follows:

The Georgia samples, which are being returned by mail, are pretty grim. They are so badly altered that it is all but impossible to convince myself that they are even vertebrate. But, an occasional chip seems to indicate that the structures visible are composed of isolated odontodes. (Odontodes, or dermal teeth, are hard structures found on the external surfaces of animals or near internal openings.) This suggests an affinity with Astrispis and other Ordovician Heterostraci (Heterostraci or "Different scales" is an extinct class of jawless vertebrates that lived primarily in marine and estuary environments.), rather than with anything later. The appalling condition of the material makes this very tentative, however.

The specimens are being retained in the National Collections.

Frank C. Whitmore, Jr.

For: Dick Lund

If these specimens represent agnathans swimming in the sea which once covered Georgia, and Dr. Carter’s comments suggest that this is at least possible, then the Southeast represents an almost complete fossil record from the Cambrian Explosion to today.