10A: Georgia & The Origins of Whales

by Thomas Thurman

Indohyus

Whales emerged into the global fossil record about 55-52 million years ago as terrestrial, placental mammals transitioning to a marine life on the edges of the extinct Tethys Ocean.

The Tethys was a large, warm, shallow, fertile ocean which once covered the equator from Europe to India. Shallow equatorial seas are always brimming with life.

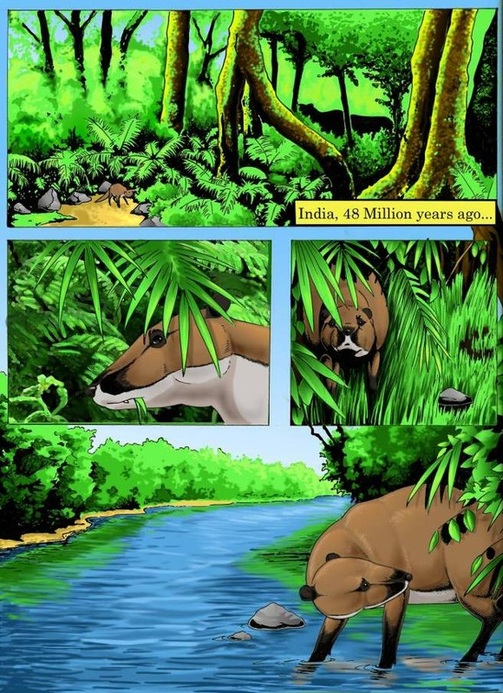

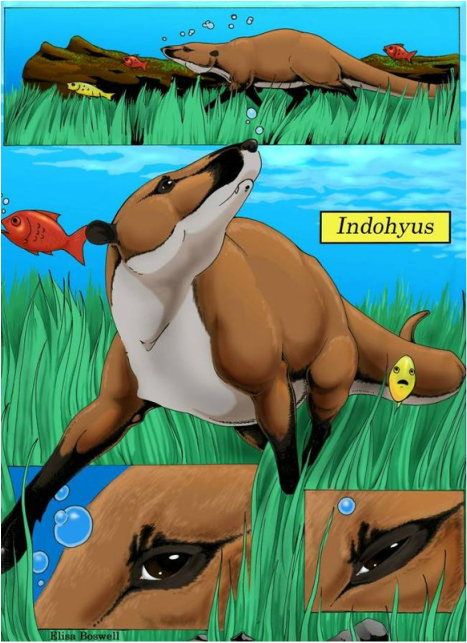

Current research ties the probable origins of whales to an extinct, small, raccoon-like animal which lived in India about 50 million years ago named Indohyus (meaning India’s Pig). Indohyus was described in 2007 by a research team headed by J.G.M. (Hans) Thewissen at Northeastern Ohio University.

Indohyus was linked to the whale family by the bone structure of its inner ear, which matches the distinct ear structure of both ancient and modern whales, a structure seen in no other line of animals.

It’s thought to have fed on land, perhaps eating plants or insects but spent most of its time in the relative safety of fresh water streams, ponds and shallow lakes. Its bone structure was relatively heavy for such a small animal, suggesting that it wasn’t so much a swimmer but walked along the bottom.

This is the same type of life the much larger modern hippo enjoys.

These superb images were created by Elisa Boswell, while she was at Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus, Georgia in 2011. These images have been reviewed and approved by J.G.M. (Hans) Thewissen, we appreciate his time, attention & comments.

Whales emerged into the global fossil record about 55-52 million years ago as terrestrial, placental mammals transitioning to a marine life on the edges of the extinct Tethys Ocean.

The Tethys was a large, warm, shallow, fertile ocean which once covered the equator from Europe to India. Shallow equatorial seas are always brimming with life.

Current research ties the probable origins of whales to an extinct, small, raccoon-like animal which lived in India about 50 million years ago named Indohyus (meaning India’s Pig). Indohyus was described in 2007 by a research team headed by J.G.M. (Hans) Thewissen at Northeastern Ohio University.

Indohyus was linked to the whale family by the bone structure of its inner ear, which matches the distinct ear structure of both ancient and modern whales, a structure seen in no other line of animals.

It’s thought to have fed on land, perhaps eating plants or insects but spent most of its time in the relative safety of fresh water streams, ponds and shallow lakes. Its bone structure was relatively heavy for such a small animal, suggesting that it wasn’t so much a swimmer but walked along the bottom.

This is the same type of life the much larger modern hippo enjoys.

These superb images were created by Elisa Boswell, while she was at Georgia Southwestern State University in Americus, Georgia in 2011. These images have been reviewed and approved by J.G.M. (Hans) Thewissen, we appreciate his time, attention & comments.

By this point in Earth’s history mammals were well established as the dominant terrestrial animals and had diversified dramatically. Hoofed animals are dominant, including hoofed carnivores which are all extinct now. Early primates were also present. Both are known from North America.

Returning to ancient India… Imagine Indohyus feeding in the dense undergrowth along a quiet stream only to be spooked by a noise or scent from the jungle, it would then retreat to the safety of the stream.

Carolinacetus

A Typical Proto- Whale

In 2005 Jonathan H. Geisler, Albert E. Sanders and Zhe-XI Lou published a paper on the discovery of another new genus and species of whale from Berkeley County, South Carolina. While not a Georgia find it relates to Georgiacetus, which we’ll look at soon in detail.

At the time of publication Dr. Geisler was an Associate Professor of Paleontology and Curator of Paleontology for the Georgia Southern Museum in Statesboro, Georgia.

They reported finding portions of a skull, the rear sections of jaws, 13 vertebrae and 15 partial ribs. The ear bones confirm a whale ancestry and the skull also shows a clear relationship to Georgiacetus.

No pelvis, leg or tail material was recovered so it was impossible to tell how this new whale swam or if it could support its own weight out of the water though research over Georgiacetus, which appears to be a more advanced whale, suggests that Carolinacetus also swam with its hind legs.

The genus and species was named Carolinacetus gingerichi in honor of Dr. Philip D. Gingerich at the University of Michigan. Gingerich is a highly respect researcher in vertebrate evolution specializing in Cenozoic mammals who has done strong research on the origins of whales.

The skull clearly showed that Carolinacetus was not as advanced an animal as Georgiacetus; but there were other similarities, especially in the teeth which are similar but more primitive, to show that the two were very closely related.

The invertebrate fossils contained in the matrix dated Carolinacetus to about 41.5 million years ago, during the Late Lutetian Stage of the Eocene Epoch; which spanned from 48.6 to 40.4 million years ago.

Carolinacetus is the oldest, most primitive whale known from North America. This kindled an interesting debate; just how did the proto-whales get here?

As mentioned earlier, Indohyus and the earliest whales originated in the Tethys Ocean which once covered much of Asia. This was the origin and nursery of all whales.

Proto-whale teeth show that they were probably fish eaters, or piscivores. The environments of the Tethys Ocean, and the sea covering our Southeast during this time were very similar. Both were shallow, warm, fertile seas capable of sustaining vast fish populations. In our case the Suwannee Current kept a wealth of nutrients circulating.

Still, the two seas were separated by almost half a hemisphere and a deep water Atlantic Ocean. The theory of continental drift, plate tectonics, shows that the Atlantic was indeed a bit narrower than today but not dramatically so, it would have represented a huge obstacle.

Of course sea levels were much higher so even though the continental plates were physically closer, higher sea levels would have meant that the coast to coast distance probably wasn’t significantly different than today and may have actually been farther.

The Earth was a warmer place and the poles were likely ice free. Greenland was green. A significantly warmer Earth means that the polar route from the Tethys Ocean to our Southeastern Sea would have been ice free; it wouldn’t require cold adapted animals.

So the mystery becomes how did the Carolinacetus (or its unknown ancestor) travel from the Tethys Ocean to our Southeastern Sea?

Two theories were put forth; one involved a direct Atlantic crossing following deep-water Atlantic fish movements.

The other involved coastal migration northwards along the polar route, up the European coast, across to Greenland, and then down the North American coastline.

Since the only known fossils all came from coastal environments the real question becomes; were these early whales capable of a sustained, deep water crossing?

The debate over this continues. One thing seems certain; Carolinacetus was an active, highly capable marine predator able to take large prey.

The skull of Carolinacetus shows a very typical proto-whale layout, the position of the nostrils and the shape of the teeth are seen in many very similar species, all from the Tethys Ocean fossil record.

These older proto-whales possessed pelvis bones firmly fused to the vertebrae, so were probably capable of hauling out. We simply cannot know if the same is true for Carolinacetus until more fossils are found.

References:

Indohyus

Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene Epoch of India. J.G.M. Thewissen, Lisa Noelle Cooper, Mark T. Clementz, Sunil Bajpai, B.N. Tiwari. Nature, Nature Publishing Group, Vol. 450, vol. 20, 27/December/2007

Carolinacetus gingerichi

A New Protocetid Whale (Cetacea: Archaeoceti) from the Late Middle Eocene of South Carolina. Jonathan H. Geisler, Albert E. Sanders and Zhe-Xi Luo. American Museum Novitates, No.3480, 25/July/2005. American Museum of Natural History

Georgiacetus vogtlensis

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archeoceti) and associated Biota From Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Jr. Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.72, No.5, 1998. The Paleontological Society

Legs as a means of propulsion:

New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Returning to ancient India… Imagine Indohyus feeding in the dense undergrowth along a quiet stream only to be spooked by a noise or scent from the jungle, it would then retreat to the safety of the stream.

Carolinacetus

A Typical Proto- Whale

In 2005 Jonathan H. Geisler, Albert E. Sanders and Zhe-XI Lou published a paper on the discovery of another new genus and species of whale from Berkeley County, South Carolina. While not a Georgia find it relates to Georgiacetus, which we’ll look at soon in detail.

At the time of publication Dr. Geisler was an Associate Professor of Paleontology and Curator of Paleontology for the Georgia Southern Museum in Statesboro, Georgia.

They reported finding portions of a skull, the rear sections of jaws, 13 vertebrae and 15 partial ribs. The ear bones confirm a whale ancestry and the skull also shows a clear relationship to Georgiacetus.

No pelvis, leg or tail material was recovered so it was impossible to tell how this new whale swam or if it could support its own weight out of the water though research over Georgiacetus, which appears to be a more advanced whale, suggests that Carolinacetus also swam with its hind legs.

The genus and species was named Carolinacetus gingerichi in honor of Dr. Philip D. Gingerich at the University of Michigan. Gingerich is a highly respect researcher in vertebrate evolution specializing in Cenozoic mammals who has done strong research on the origins of whales.

The skull clearly showed that Carolinacetus was not as advanced an animal as Georgiacetus; but there were other similarities, especially in the teeth which are similar but more primitive, to show that the two were very closely related.

The invertebrate fossils contained in the matrix dated Carolinacetus to about 41.5 million years ago, during the Late Lutetian Stage of the Eocene Epoch; which spanned from 48.6 to 40.4 million years ago.

Carolinacetus is the oldest, most primitive whale known from North America. This kindled an interesting debate; just how did the proto-whales get here?

As mentioned earlier, Indohyus and the earliest whales originated in the Tethys Ocean which once covered much of Asia. This was the origin and nursery of all whales.

Proto-whale teeth show that they were probably fish eaters, or piscivores. The environments of the Tethys Ocean, and the sea covering our Southeast during this time were very similar. Both were shallow, warm, fertile seas capable of sustaining vast fish populations. In our case the Suwannee Current kept a wealth of nutrients circulating.

Still, the two seas were separated by almost half a hemisphere and a deep water Atlantic Ocean. The theory of continental drift, plate tectonics, shows that the Atlantic was indeed a bit narrower than today but not dramatically so, it would have represented a huge obstacle.

Of course sea levels were much higher so even though the continental plates were physically closer, higher sea levels would have meant that the coast to coast distance probably wasn’t significantly different than today and may have actually been farther.

The Earth was a warmer place and the poles were likely ice free. Greenland was green. A significantly warmer Earth means that the polar route from the Tethys Ocean to our Southeastern Sea would have been ice free; it wouldn’t require cold adapted animals.

So the mystery becomes how did the Carolinacetus (or its unknown ancestor) travel from the Tethys Ocean to our Southeastern Sea?

Two theories were put forth; one involved a direct Atlantic crossing following deep-water Atlantic fish movements.

The other involved coastal migration northwards along the polar route, up the European coast, across to Greenland, and then down the North American coastline.

Since the only known fossils all came from coastal environments the real question becomes; were these early whales capable of a sustained, deep water crossing?

The debate over this continues. One thing seems certain; Carolinacetus was an active, highly capable marine predator able to take large prey.

The skull of Carolinacetus shows a very typical proto-whale layout, the position of the nostrils and the shape of the teeth are seen in many very similar species, all from the Tethys Ocean fossil record.

These older proto-whales possessed pelvis bones firmly fused to the vertebrae, so were probably capable of hauling out. We simply cannot know if the same is true for Carolinacetus until more fossils are found.

References:

Indohyus

Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene Epoch of India. J.G.M. Thewissen, Lisa Noelle Cooper, Mark T. Clementz, Sunil Bajpai, B.N. Tiwari. Nature, Nature Publishing Group, Vol. 450, vol. 20, 27/December/2007

Carolinacetus gingerichi

A New Protocetid Whale (Cetacea: Archaeoceti) from the Late Middle Eocene of South Carolina. Jonathan H. Geisler, Albert E. Sanders and Zhe-Xi Luo. American Museum Novitates, No.3480, 25/July/2005. American Museum of Natural History

Georgiacetus vogtlensis

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archeoceti) and associated Biota From Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Jr. Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.72, No.5, 1998. The Paleontological Society

Legs as a means of propulsion:

New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.