|

|

|

20A: Clark Quarry

Mammoths & Bison

From Coastal Georgia

By

Thomas Thurman

Clark Quarry; Brunswick, Georgia

Don’t go looking for the Clark quarry on Goggle Earth, you won’t find it. This is not a mining quarry in the traditional sense and it doesn’t exist in the industrial sense.

Dr. Al Mead from Georgia College Natural History Museum relates the story on how Clark Quarry came to be. The Clark brothers, twins, in Brunswick were looking for amphibians in the swampy area of their family’s property. They were near the site where in 1838-1839 a canal had been constructed to connect the Altamaha River with the Turtle River. The Clark boys weren’t aware that during the construction of the canal fossils of several large mammals were unearthed. The brothers also stumbled across large fossils.

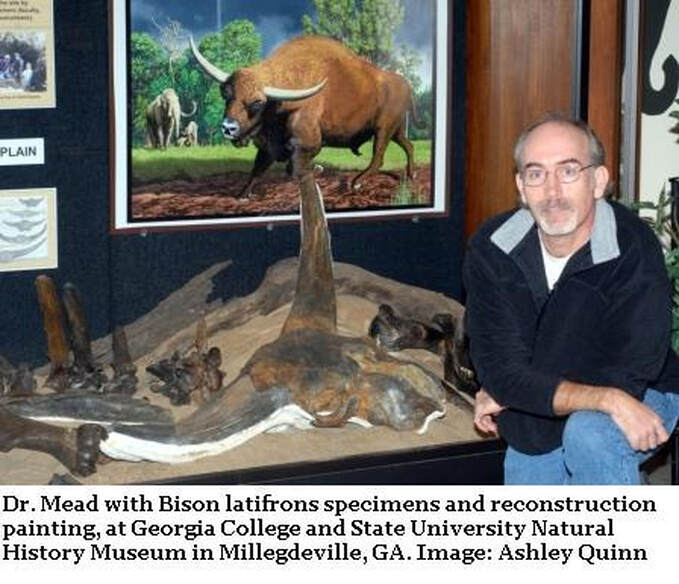

As Dr. Mead explained during a talk to the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society, the Clark family is very science oriented so fortunately the fossils made their way to university paleontologists and eventually found Dr. Mead who recognized them as juvenile mammoth remains.

With the family’s blessings, assistance, and the active involvement of the Clark brothers, the staff and students of Georgia College began quarrying by hand as the local water table allowed.

With the family’s blessings, assistance, and the active involvement of the Clark brothers, the staff and students of Georgia College began quarrying by hand as the local water table allowed.

“The fossil site is beneath a small rise.” Dr. Meade relates that to gain access to the quarry you usually had to wade through a swampy area, actually floating the wheel-barrows at one point. On-site they dig down vertically with hand-held shovels, through several feet of the typical dense mud found in the area until they strike the sandy layer holding the fossil bed. They then follow the fossil bed horizontally. As quarrying progressed they backfill behind them so that the actual work area, the quarry, is never more than a few meters square.

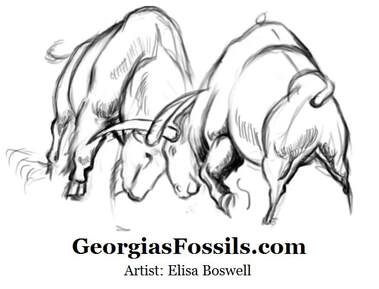

The Giant Bison

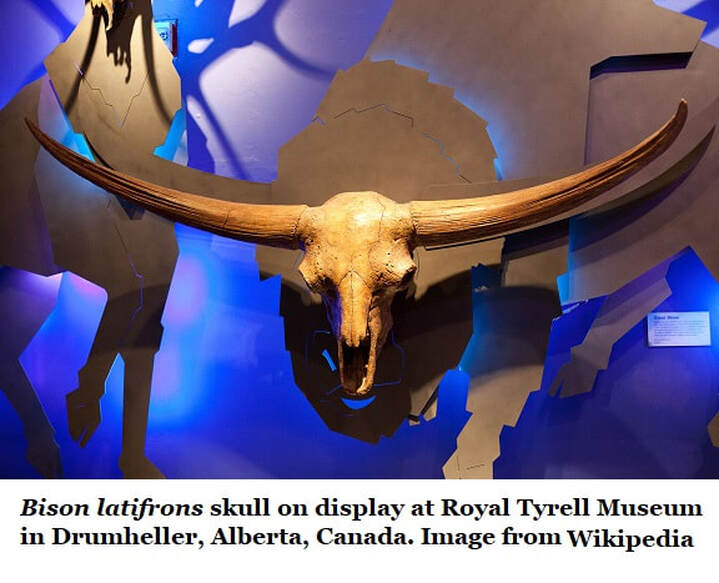

The giant bison; Bison latifrons is well represented in the Clark Quarry deposits. This was a large animal standing 8.5 feet at the shoulders; maybe 20% larger than the modern bison (Bison bison) which are large animals by any standard.

In life horn spreads are seven feet and more. It was closely related to modern bison and would have looked very much the same except for the larger size and more prominent horns.

The modern Bison bison has a horn spread of about 2 feet.

The giant bison; Bison latifrons is well represented in the Clark Quarry deposits. This was a large animal standing 8.5 feet at the shoulders; maybe 20% larger than the modern bison (Bison bison) which are large animals by any standard.

In life horn spreads are seven feet and more. It was closely related to modern bison and would have looked very much the same except for the larger size and more prominent horns.

The modern Bison bison has a horn spread of about 2 feet.

Dr. Mead points out that only known way to confirm an individual as a giant bison is through the dimensions of the skull or horns.

The fossil record for the giant bison is widely distributed despite the fact that its occurrence is rare when compared to mastodons or mammoths. It is known from Canada, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Missouri, Ohio, Kentucky, Georgia and Florida.

The fossil record for the giant bison is widely distributed despite the fact that its occurrence is rare when compared to mastodons or mammoths. It is known from Canada, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Missouri, Ohio, Kentucky, Georgia and Florida.

Bison latifrons remains from Clark Quarry include a nearly complete skull with intact left horn core and a partial right horn core. The estimated horn core spread is 5.31 feet. In life these would have been sheathed in keratin horn material and Mead estimates a 7 foot spread of horns for the living animal.

Numerous vertebrae were found as well as ribs, leg bones and other material. Up to six individuals are represented in the recovered finds. The remains have been dated to about 21,000 years ago.

Bison latifrons remains from Clark Quarry include a nearly complete skull with intact left horn core and a partial right horn core. The estimated horn core spread is 5.31 feet. In life these would have been sheathed in keratin horn material and Mead estimates a 7 foot spread of horns for the living animal.

Numerous vertebrae were found as well as ribs, leg bones and other material. Up to six individuals are represented in the recovered finds. The remains have been dated to about 21,000 years ago.

Update: In October 2016; Ashley Quinn reported that the right horn core from the skull had been reassembled from fragmentary material collected during the excavation and now the museum's Bison latifrons skull is complete.

The Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi

The majority of the large fossils found in the Clark Quarry belonged to the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), an animal whose story also begins here in Georgia.

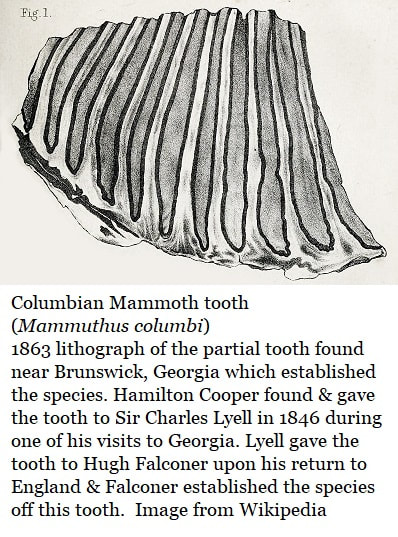

The Columbian mammoth was described and established as a species from a partial tooth collected at the Watkins Quarry in Brunswick, Georgia about 2 kilometers away from the Clark Quarry.

The majority of the large fossils found in the Clark Quarry belonged to the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), an animal whose story also begins here in Georgia.

The Columbian mammoth was described and established as a species from a partial tooth collected at the Watkins Quarry in Brunswick, Georgia about 2 kilometers away from the Clark Quarry.

|

The tooth was discovered by Hamilton Cooper during the construction of the Brunswick Canal in 1838 to 1839.

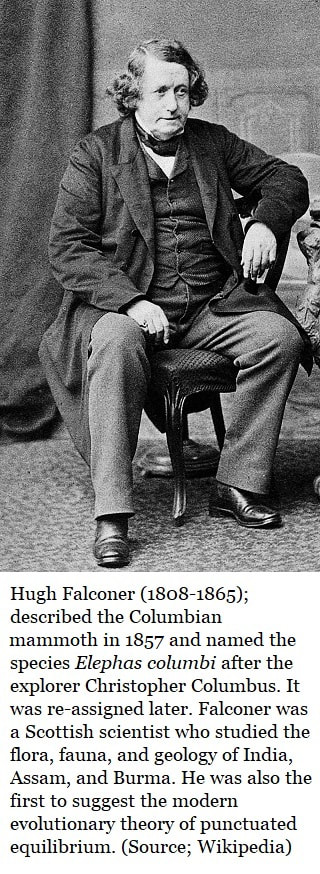

It was passed along to the famous British scientist and father of modern geology Sir Charles Lyell during his visit to Georgia in 1846. Lyell passed the tooth to Hugh Flaconer who used it to established a new species which he named Elephas columbi it was later reassigned as Mammuthus columbi. Of a historical note; Lyell was a favorite author of Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle, and when they met upon Darwin’s return to England the two became close friends; Lyell took the role of mentor for Darwin and guided him in England’s social world. |

In life the Columbian Mammoth was primarily a grazer (eating grasses) and a member of the elephant family (where the mastodon was a browser); mammoths are known to have ranged from Florida to California and southward well into Mexico.

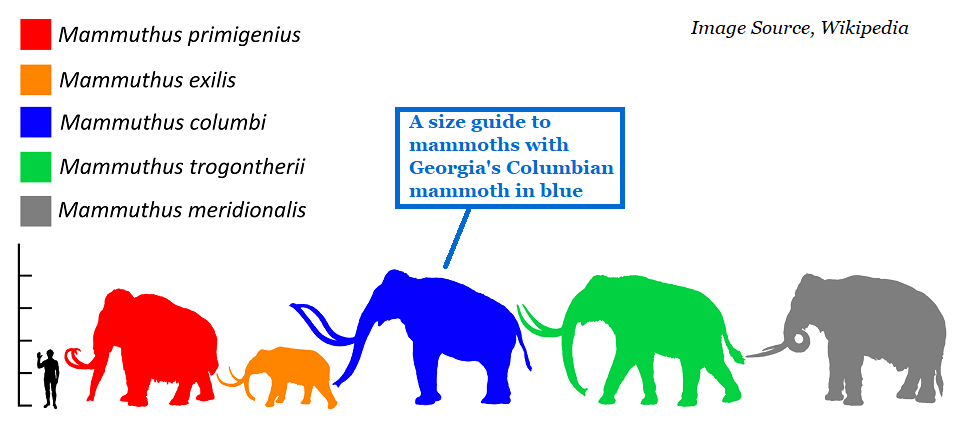

The Columbian Mammoth was one of the largest elephants to have ever lived and stood up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder, about 10.7 feet long, and weighing in around 11 tons.

The spiraled tusks typically ran 6.5 feet long though the longest recorded Columbian mammoth tusks are 16 feet long, these are the longest known tusks known from any elephant species.

The Columbian Mammoth was one of the largest elephants to have ever lived and stood up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder, about 10.7 feet long, and weighing in around 11 tons.

The spiraled tusks typically ran 6.5 feet long though the longest recorded Columbian mammoth tusks are 16 feet long, these are the longest known tusks known from any elephant species.

It did not possess the coat of hair known to wooly mammoths and mastodons, but perhaps had hair on the head or back. It looked very much like a large modern elephant, though their backs sloped more than living species.

Columbian mammoth finds from the Clark Quarry include a juvenile partial jaw, adult tooth plates and tusk fragments, vertebrae, ribs, long bones and others. These are clearly the remains of multiple animals. Remains from at least one female and calf were also recovered.

Columbian mammoth finds from the Clark Quarry include a juvenile partial jaw, adult tooth plates and tusk fragments, vertebrae, ribs, long bones and others. These are clearly the remains of multiple animals. Remains from at least one female and calf were also recovered.

Dr. Mead describes how mammoths had a huge impact on their environment. He compared them to modern elephants and how their herd behavior and huge appetites had a tendency to both maintain and expand grasslands by culling trees and consuming tree seedlings. Their feeding activities would have benefited other grazers and grassland predators.

Mead argues successfully that like modern elephants our mammoths likely dominated their contemporary Georgia environment, and like humans, modified it through their feeding activities to their needs. Due in large part to their activity, much of Georgia wasn’t forested during their reign, it was a grassland prairie.

Mead argues successfully that like modern elephants our mammoths likely dominated their contemporary Georgia environment, and like humans, modified it through their feeding activities to their needs. Due in large part to their activity, much of Georgia wasn’t forested during their reign, it was a grassland prairie.

Humans as a species; Homo sapiens sapiens

Our species; Homo sapiens sapiens (showing our genus, species and sub-species), emerged and radiated out of Africa about 200,000 years ago.

We probably originated from the species Homo heidelbergensis (also known as Homo rhodesiensis) which was preceded by Homo erectus.

There were other species of Homo sapiens walking the Earth at this same time; at least Homo sapiens neanderthalensis in Europe and Homo sapiens idaltu in Africa.

By 50,000 years ago our ancestors show fully modern behavior. All humans today are members of this same species and sub-species. This means we are all the same. Our differences in the last 50,000 years and across the globe are purely cultural, technological and educational.

The only real differences between humans 50,000 years ago and humans today are immunities to modern diseases.

The last glacial maximum occurred about 20,000 years ago, currently there is no broadly accepted evidence that humans were present in North America at that time, though it is certainly possible.

We were present in Europe. Research shows that Italy and Eurasia acted as a European refuge during the last glacial maximum for the Northern Hemisphere human populations.

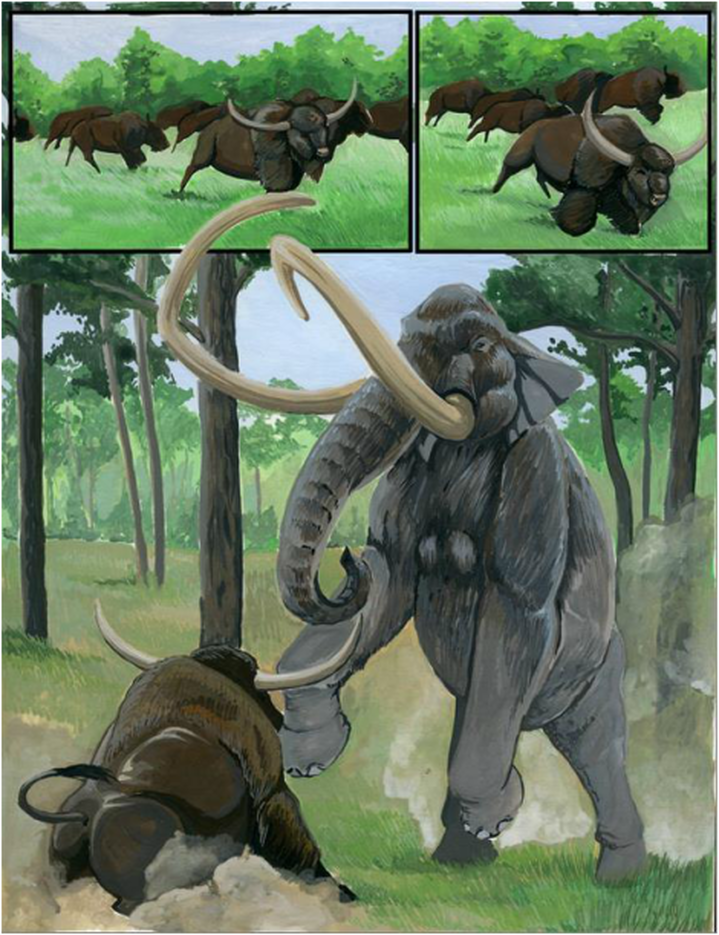

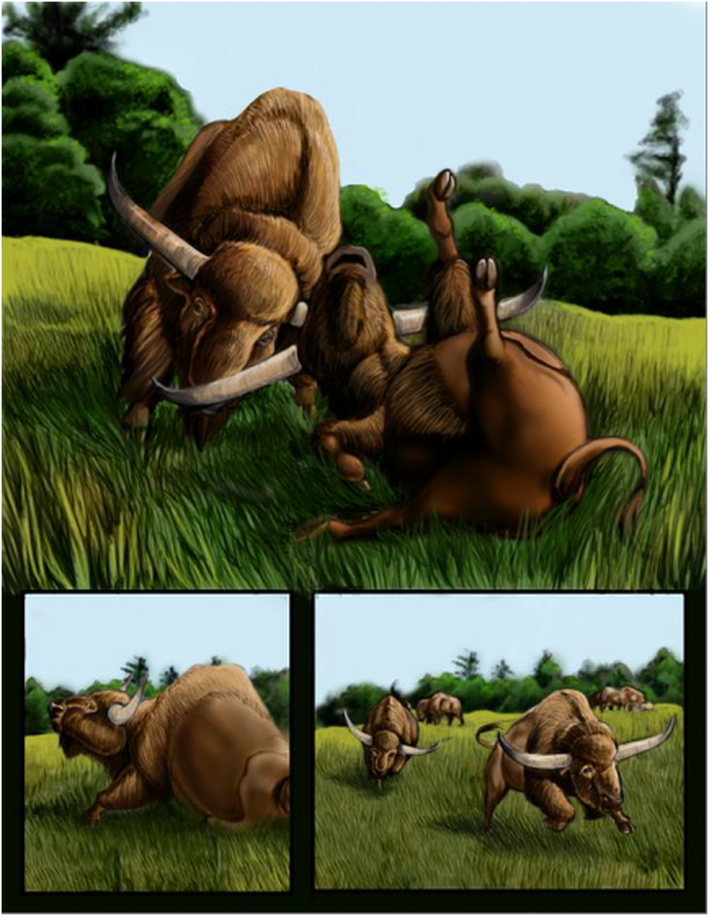

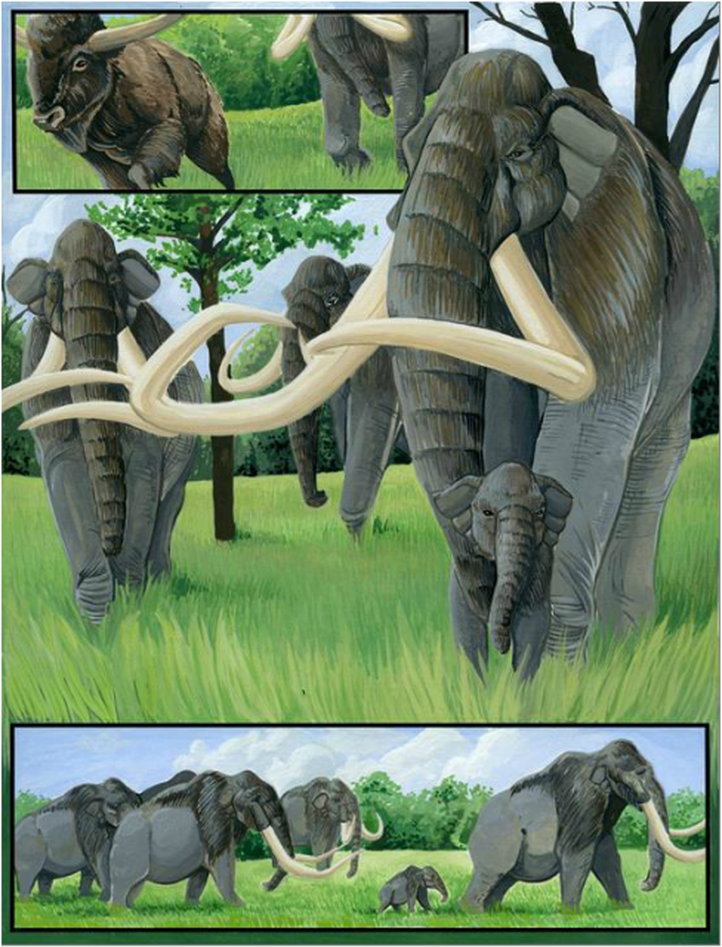

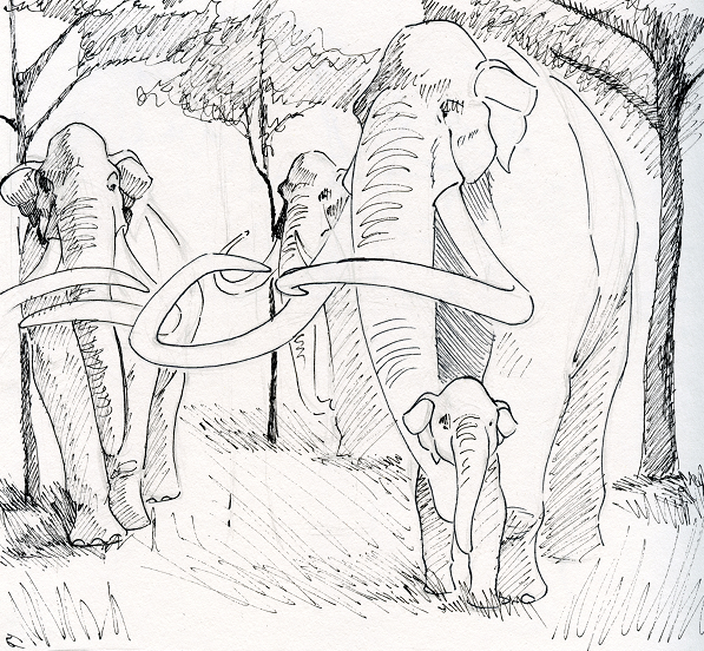

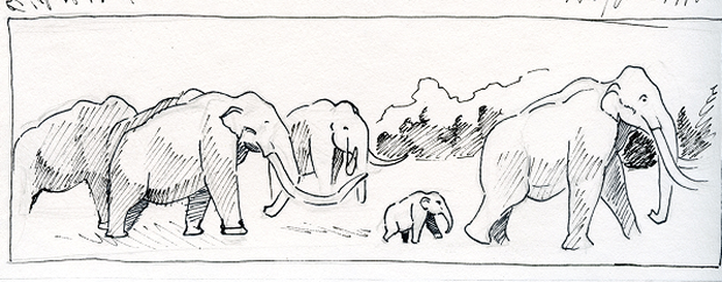

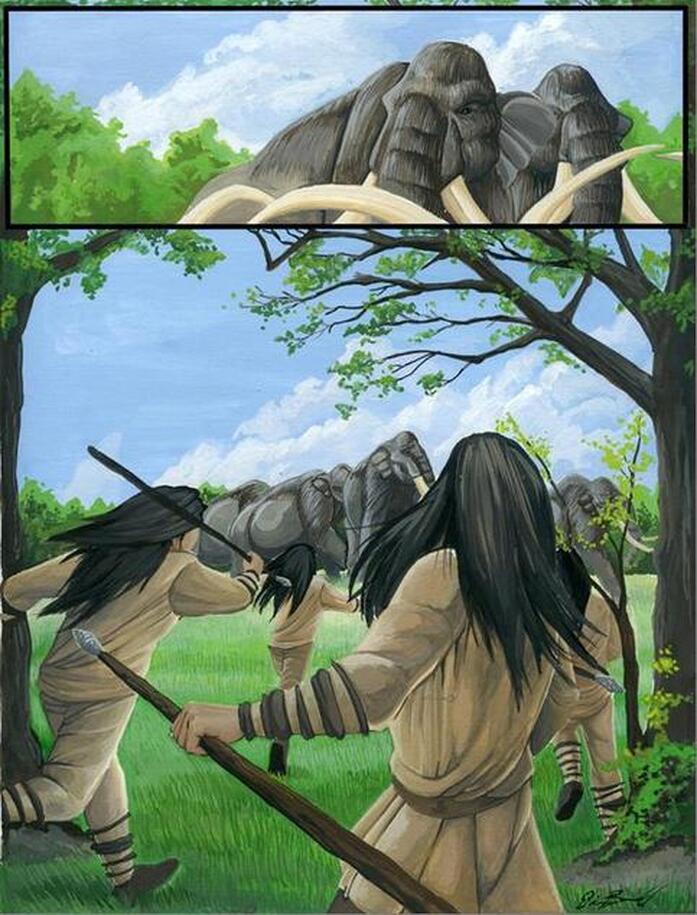

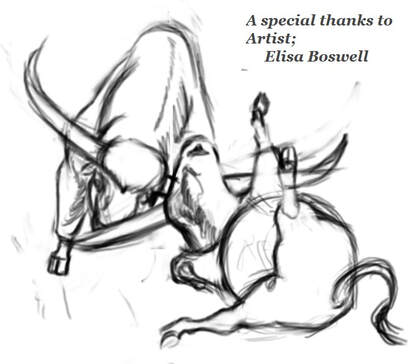

Artist; Elisa Boswell created these images in 2012; she depicts the giant bison Bison latifrons, The Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi and the arrival of man.

This collection of images needs a bit of explanation as they were not intended to convey a single moment in time.

Both the giant bison and Columbian mammoth have been shown to be present in Georgia at about 21,000 years ago. The Columbian mammoth endured to at least 12,500 years ago (maybe to 9,000 years ago or less).

The US National Park Service states that the Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon has had a continuous human presence for the last 12,000 years. www.ocmulgeemounds.org/about

(There is ongoing debate over when humans entered North America and the Southeast.)

Though there is no evidence of what prey was hunted in Georgia there is evidence nationally that the first humans in North America (the Clovis people) hunted mammoths, mastodons, bison (we don’t know which species), as well as the typical small game.

After some debate with researchers from several disciplines Ms. Boswell was asked to create the following these images.

The first humans in North America were a cold climate people. They are typically represented as primitives in loin cloths. Bearing in mind that they're of the same species as us, and just a capable, I steered Ms. Boswell away from this stereotypical naked-native depiction, instead I had her depict them in a fashion similar to the “traditional” appearance of plains Indians.

This collection of images needs a bit of explanation as they were not intended to convey a single moment in time.

Both the giant bison and Columbian mammoth have been shown to be present in Georgia at about 21,000 years ago. The Columbian mammoth endured to at least 12,500 years ago (maybe to 9,000 years ago or less).

The US National Park Service states that the Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon has had a continuous human presence for the last 12,000 years. www.ocmulgeemounds.org/about

(There is ongoing debate over when humans entered North America and the Southeast.)

Though there is no evidence of what prey was hunted in Georgia there is evidence nationally that the first humans in North America (the Clovis people) hunted mammoths, mastodons, bison (we don’t know which species), as well as the typical small game.

After some debate with researchers from several disciplines Ms. Boswell was asked to create the following these images.

The first humans in North America were a cold climate people. They are typically represented as primitives in loin cloths. Bearing in mind that they're of the same species as us, and just a capable, I steered Ms. Boswell away from this stereotypical naked-native depiction, instead I had her depict them in a fashion similar to the “traditional” appearance of plains Indians.

References:

Sea Level change

The Phanerozoic Record of Global Sea-Level Change

Kenneth G. Miller, Michelle A. Kominz, James V. Browning, James D. Wright, Gregory S. Mountain, Miriam E. Katz, Peter J. Sugarman, Benjamin S. Cramer, Nicholas Christie-Blick, Stephen F. Pekar. Science, Vol. 310, 25 Nov 2005

Twenty-seven sea level changes;

A warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider & Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, 2009, Pg. 194, Cambridge Philosophical Society

Eolian Dunes;

Riverine dunes on the Coastal Plain of Georgia, USA. Andrew H. Ivester & David S. Leigh, Geomorphology, 1253, 2002. Published by Elsevier Science B.V

Mystery of the Misplaced Dunes. By Lucy Justus. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine. 22/Feburary/1976 (Sam Pickering advised)

Carolina Bays of Georgia

Van DeGenachte, E., and S. Cammack. 2002. Carolina bays of Georgia: Their distribution, condition, and conservation. Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Social Circle.

Mammut americanum:

First Mastodont remains From the Chattahoochee River Valley in Western Georgia, With Implications for the Age of Adjacent Stream Terraces. David R. Schwimmer. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.49, Pgs.81-86. 2001, Georgia Academy of Sciences

Clark Quarry

Preliminary Comments on the Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Clark Quarry, Brunswick, Georgia. Alfred J. Mead, Robert A. Bahn, Robert M. Chandler and Dennis Parmley. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates, Vol.23. 2006

Sea level change numbers & Southeastern ice age refuge info:

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Lists of Pleistocene Fossils:

New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Early reports from the Georgia Coast:

Prehistoric Vertebrates of the Georgia Coastal Plain. Georgia Mineral Newsletter Vol. X, No. 3, Autumn 1957 By: Vernon Hurst 1957

Sea Level change

The Phanerozoic Record of Global Sea-Level Change

Kenneth G. Miller, Michelle A. Kominz, James V. Browning, James D. Wright, Gregory S. Mountain, Miriam E. Katz, Peter J. Sugarman, Benjamin S. Cramer, Nicholas Christie-Blick, Stephen F. Pekar. Science, Vol. 310, 25 Nov 2005

Twenty-seven sea level changes;

A warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider & Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, 2009, Pg. 194, Cambridge Philosophical Society

Eolian Dunes;

Riverine dunes on the Coastal Plain of Georgia, USA. Andrew H. Ivester & David S. Leigh, Geomorphology, 1253, 2002. Published by Elsevier Science B.V

Mystery of the Misplaced Dunes. By Lucy Justus. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine. 22/Feburary/1976 (Sam Pickering advised)

Carolina Bays of Georgia

Van DeGenachte, E., and S. Cammack. 2002. Carolina bays of Georgia: Their distribution, condition, and conservation. Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Social Circle.

Mammut americanum:

First Mastodont remains From the Chattahoochee River Valley in Western Georgia, With Implications for the Age of Adjacent Stream Terraces. David R. Schwimmer. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.49, Pgs.81-86. 2001, Georgia Academy of Sciences

Clark Quarry

Preliminary Comments on the Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Clark Quarry, Brunswick, Georgia. Alfred J. Mead, Robert A. Bahn, Robert M. Chandler and Dennis Parmley. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates, Vol.23. 2006

Sea level change numbers & Southeastern ice age refuge info:

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Lists of Pleistocene Fossils:

New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Early reports from the Georgia Coast:

Prehistoric Vertebrates of the Georgia Coastal Plain. Georgia Mineral Newsletter Vol. X, No. 3, Autumn 1957 By: Vernon Hurst 1957