25I; I, Periarchus

(A Fossil's Tale)

By Thomas Thurman

(A Fossil's Tale)

By Thomas Thurman

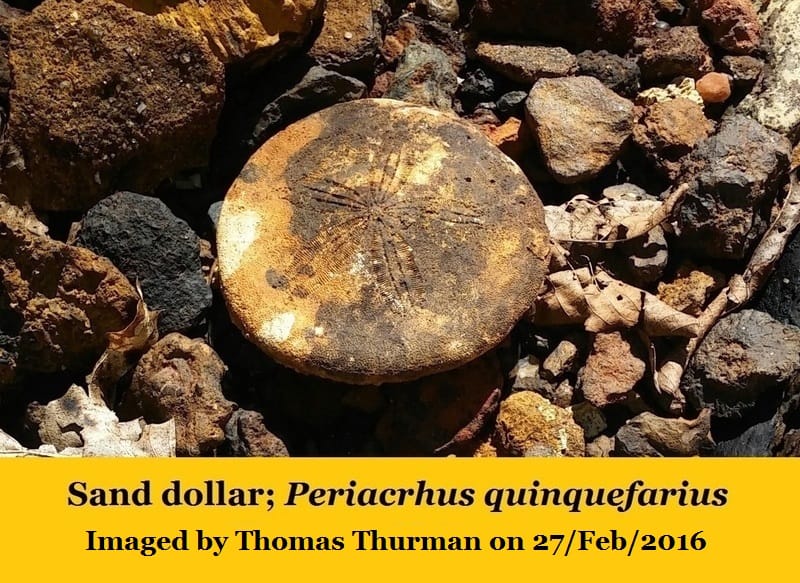

My name is Periarchus quinquefarius (kwen-cue-far-e-us).

I’m a sand dollar that lived 34 million years ago (1); roughly halfway between the demise of the dinosaurs (65 million years ago) and the emergence of your species, modern humans, two hundred thousand years ago.

I lived just before the Eocene, Oligocene extinction event 33.9 million years ago.

My whole life was spent in a small part of what is now Oaky Woods Wildlife Management Area in Houston County, Georgia. More than 150 miles inland from the nearest modern coastline.

I lived quietly beneath waves of a warm sea, just beneath the sand, feeding on the tiny bits of debris from the fertile waters.

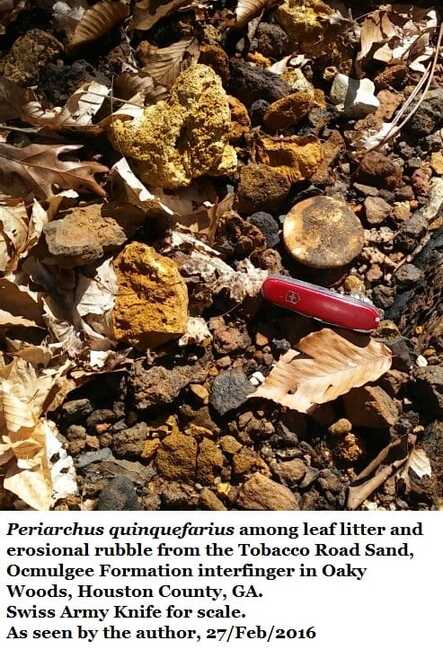

I was found in 2016 by an amateur paleontologist during a research hike among the forest’s ravines, he was trying to prove an hypothesis and I was the evidence he sought.

It is against your laws to collect fossils or artifacts in a Wildlife Management Area so he created a record and left me in peace.

I’m a sand dollar that lived 34 million years ago (1); roughly halfway between the demise of the dinosaurs (65 million years ago) and the emergence of your species, modern humans, two hundred thousand years ago.

I lived just before the Eocene, Oligocene extinction event 33.9 million years ago.

My whole life was spent in a small part of what is now Oaky Woods Wildlife Management Area in Houston County, Georgia. More than 150 miles inland from the nearest modern coastline.

I lived quietly beneath waves of a warm sea, just beneath the sand, feeding on the tiny bits of debris from the fertile waters.

I was found in 2016 by an amateur paleontologist during a research hike among the forest’s ravines, he was trying to prove an hypothesis and I was the evidence he sought.

It is against your laws to collect fossils or artifacts in a Wildlife Management Area so he created a record and left me in peace.

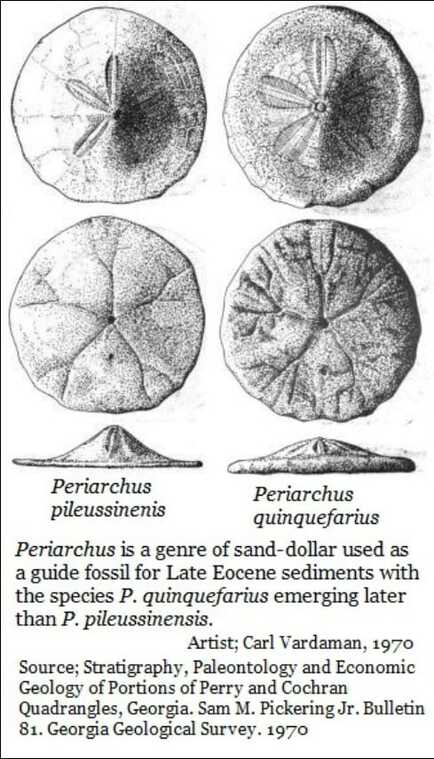

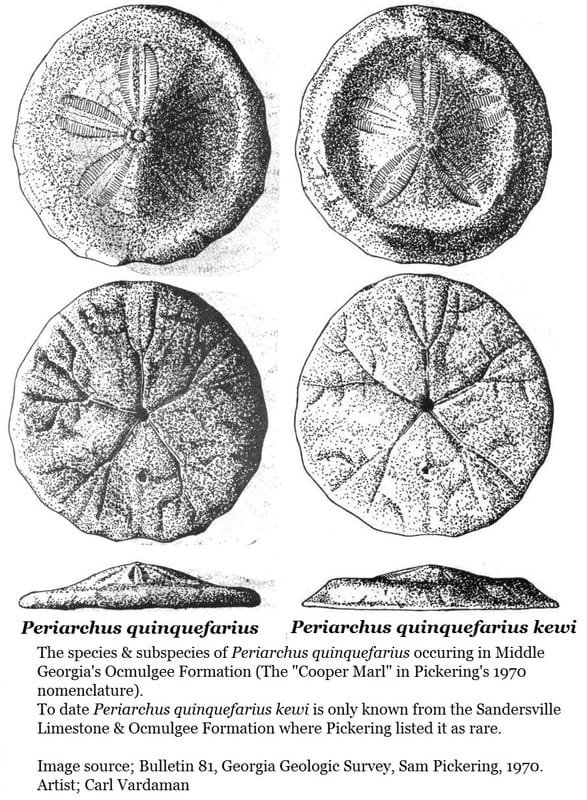

Members of my class, family & genus were diverse, widespread and numerous in the waters which once covered the Southeast, each species having its own needs and proliferating in slightly different conditions. Together we are all called echinoids.

When I lived at the end of the Eocene Epoch there were 43 species or subspecies of echinoids living in the sea then covering Eastern North America. (2) We thrived in those waters until the world changed.

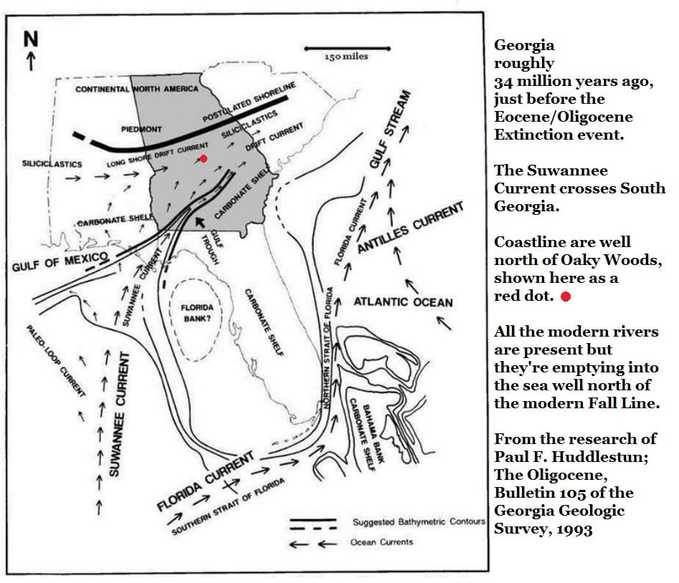

At 34 million years ago the long warm Earth of the Eocene Epoch ended in a global cooling and glacial event. Coastlines fell dramatically, for Georgia that was 228 miles all the way to the Continental Shelf, leaving these hills far inland. (3)

My genus, Periarchus, passed into history.

At 34 million years ago the long warm Earth of the Eocene Epoch ended in a global cooling and glacial event. Coastlines fell dramatically, for Georgia that was 228 miles all the way to the Continental Shelf, leaving these hills far inland. (3)

My genus, Periarchus, passed into history.

With the beginning of the Oligocene Epoch, 33.9 million years ago, the world warmed again and coastlines returned to these hills.

Only a scant handful of echinoid species from my time survived that extinction event.

A few more emerged in the Early Oligocene.

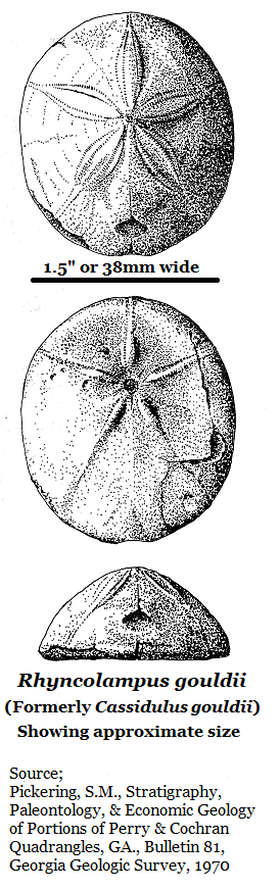

One guide fossil from the Early Oligocene was the small, thumb-sized sea urchin Rhyncolampus gouldii, which had not yet emerged when I lived but is known from nearby Early Oligocene sediments. (2)

Happily my relatives endured and they remain today leading very similar lives in warm seas far from the forested hills of Oaky Woods.

For more than thirty million years and through dozens of sea levels changes, my shell rested in these hills of Middle Georgia.

Long after I died and during one of the many low stands in sea levels, mineral laden groundwater inundated the rocks around me and slowly turned my calcium shell into rugged, enduring chert; my limestone was replaced with silica.

The amateur paleontologist placed a single drop of weak acid on me; no reaction, proof that I was no longer limestone. He neutralized the acid and rinsed it away with his water bottle.

Limestone reacts actively to acid, a drop of acid bubbles vigorously. Chert has no reaction to acid.

Only a scant handful of echinoid species from my time survived that extinction event.

A few more emerged in the Early Oligocene.

One guide fossil from the Early Oligocene was the small, thumb-sized sea urchin Rhyncolampus gouldii, which had not yet emerged when I lived but is known from nearby Early Oligocene sediments. (2)

Happily my relatives endured and they remain today leading very similar lives in warm seas far from the forested hills of Oaky Woods.

For more than thirty million years and through dozens of sea levels changes, my shell rested in these hills of Middle Georgia.

Long after I died and during one of the many low stands in sea levels, mineral laden groundwater inundated the rocks around me and slowly turned my calcium shell into rugged, enduring chert; my limestone was replaced with silica.

The amateur paleontologist placed a single drop of weak acid on me; no reaction, proof that I was no longer limestone. He neutralized the acid and rinsed it away with his water bottle.

Limestone reacts actively to acid, a drop of acid bubbles vigorously. Chert has no reaction to acid.

The rock which held me is known as the Tobacco Road Sand Formation. It’s found about halfway up a gentle ridge and is formed of terrestrial sands and clays deposited into that Southeastern sea by the paleo-Ocmulgee River.

The formation is brick red, the color comes from oxidized iron, rust. Another gift from that silica-rich, iron-rich groundwater.

In Oaky Woods there are three beds of fossils in the Tobacco Road Sand, one atop the other, separated by beds of fine grained sandy clay. All three beds contain Periarchus fossils like me.

But I’m different from the other Periarchus quinquefarius of the Tobacco Road Sand. I’m a bit lighter in color and my coloration is mottled, I’m a calico. I am chert like all the fossils in this formation, so I am of the Tobacco Road Sand, but I lack that continuous and brick-red coloration seen in other fossils of the formation.

The formation is brick red, the color comes from oxidized iron, rust. Another gift from that silica-rich, iron-rich groundwater.

In Oaky Woods there are three beds of fossils in the Tobacco Road Sand, one atop the other, separated by beds of fine grained sandy clay. All three beds contain Periarchus fossils like me.

But I’m different from the other Periarchus quinquefarius of the Tobacco Road Sand. I’m a bit lighter in color and my coloration is mottled, I’m a calico. I am chert like all the fossils in this formation, so I am of the Tobacco Road Sand, but I lack that continuous and brick-red coloration seen in other fossils of the formation.

That’s why the amateur paleontologist considered me the evidence he sought.

Somewhat below the position I knew for so long the sediments change. There the Ocmulgee Formation is found. It’s completely different though the same age and a product of that same sea.

It’s a marine deposit; pure limestone, sands and clays. Though highly variable, it was built by the sea and is rich in sea shells. All of the Ocmulgee Formation reacts actively to weak acids.

The coloration of the Ocmulgee Formation is orangish-beige to dove gray. Members of my own species, and my close cousins, are numerous.

In Oaky Woods the Tobacco Road Sand is atop the Ocmulgee Formation, in other locations the Ocmulgee overlies the Tobacco Roads Sand. In many places only one or the other occurs. It just depends on local conditions when they were formed.

The Ocmulgee Formation occurs seaward, the Tobacco Road Sand hugs what was once the coastline.

Somewhat below the position I knew for so long the sediments change. There the Ocmulgee Formation is found. It’s completely different though the same age and a product of that same sea.

It’s a marine deposit; pure limestone, sands and clays. Though highly variable, it was built by the sea and is rich in sea shells. All of the Ocmulgee Formation reacts actively to weak acids.

The coloration of the Ocmulgee Formation is orangish-beige to dove gray. Members of my own species, and my close cousins, are numerous.

In Oaky Woods the Tobacco Road Sand is atop the Ocmulgee Formation, in other locations the Ocmulgee overlies the Tobacco Roads Sand. In many places only one or the other occurs. It just depends on local conditions when they were formed.

The Ocmulgee Formation occurs seaward, the Tobacco Road Sand hugs what was once the coastline.

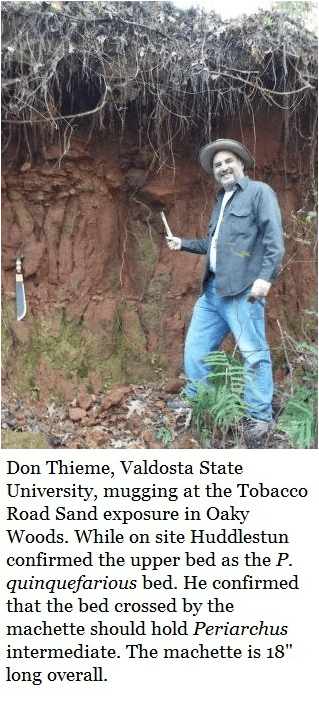

In 1978 Paleontologist Paul F. Huddlestun, working for the Georgia Geological Survey, described this area as barrier islands and lagoons from 34 million years ago.

He explained that the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation interfinger. (4)

He showed that where the two occur together barrier islands once existed.

At the time Mr. Paul didn’t know the Ocmulgee Formation occurred so far north, that was discovered and reported by the amateur paleontologist who found me.

The amateur also found the Ocmulgee Formation at the base of the same ridge which held the Tobacco Road Sand, so he went looking for evidence that the two formations made contact in that ridge.

The ancient Ocmulgee River drained into my warm sea northward of where Oaky Woods is today; bringing the nutrients which powered a diverse ecosystem.

All of Georgia’s rivers are very old. I lived on the edge of a barrier island, protected from the rages of the sea itself but enjoying it’s benefits.

He explained that the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation interfinger. (4)

He showed that where the two occur together barrier islands once existed.

At the time Mr. Paul didn’t know the Ocmulgee Formation occurred so far north, that was discovered and reported by the amateur paleontologist who found me.

The amateur also found the Ocmulgee Formation at the base of the same ridge which held the Tobacco Road Sand, so he went looking for evidence that the two formations made contact in that ridge.

The ancient Ocmulgee River drained into my warm sea northward of where Oaky Woods is today; bringing the nutrients which powered a diverse ecosystem.

All of Georgia’s rivers are very old. I lived on the edge of a barrier island, protected from the rages of the sea itself but enjoying it’s benefits.

To the south a powerful current crossed Georgia when that sea existed; rising in the Caribbean and emptying in the Atlantic it was called the Suwannee Current, it dispersed the river-borne sediments and kept my sea active and fertile. (5, 3)

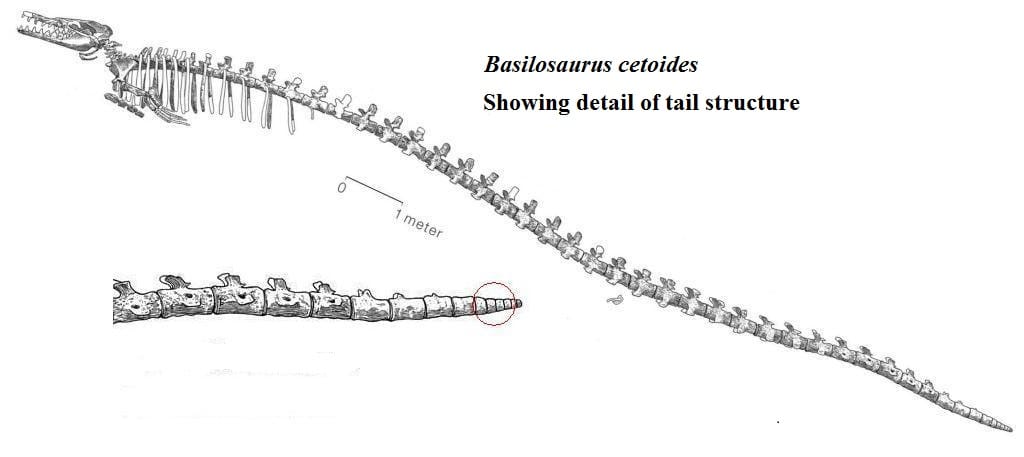

The first great whales swam that sea; the basilosaurids, this was before baleen whales existed.

The largest (Basilosaurus cetoides) grew to more than eighty feet in length and was common in these waters. The basilosaurids are the ancestors to modern whales, but they were different. (6)

The basilosaurids had tiny hind legs but had already lost the ability to return to land, their hips were unattached to their spine. They could not support their own weight out of the water and spent their whole lives at sea.

Modern whales still possess a tiny, atrophied pelvis within their bodies.

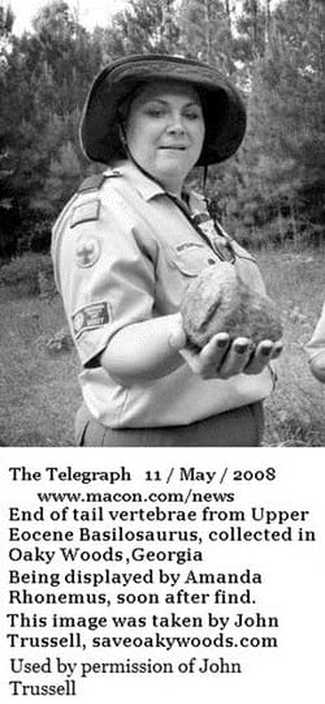

In 2008 a group of Scouts found an end-of-tail basilosaurus whale vertebra at this same ridge, it was from the Ocmulgee Formation.

The barrier islands were good hunting grounds rich in prey.

There were smaller early whales too; ranging from ten to thirty feet in length. All of them were efficient predators and in the basilosaurid family. (6)

Their teeth were terrible. The front teeth were large spikes which gripped struggling, slippery prey, and there were large triangular molars further back for shearing larger prey into manageable chunks.

The first great whales swam that sea; the basilosaurids, this was before baleen whales existed.

The largest (Basilosaurus cetoides) grew to more than eighty feet in length and was common in these waters. The basilosaurids are the ancestors to modern whales, but they were different. (6)

The basilosaurids had tiny hind legs but had already lost the ability to return to land, their hips were unattached to their spine. They could not support their own weight out of the water and spent their whole lives at sea.

Modern whales still possess a tiny, atrophied pelvis within their bodies.

In 2008 a group of Scouts found an end-of-tail basilosaurus whale vertebra at this same ridge, it was from the Ocmulgee Formation.

The barrier islands were good hunting grounds rich in prey.

There were smaller early whales too; ranging from ten to thirty feet in length. All of them were efficient predators and in the basilosaurid family. (6)

Their teeth were terrible. The front teeth were large spikes which gripped struggling, slippery prey, and there were large triangular molars further back for shearing larger prey into manageable chunks.

The warm water adapted basilosaurids also found extinction with the glacial event at the end of the Eocene. Thankfully their ancestors are still with us.

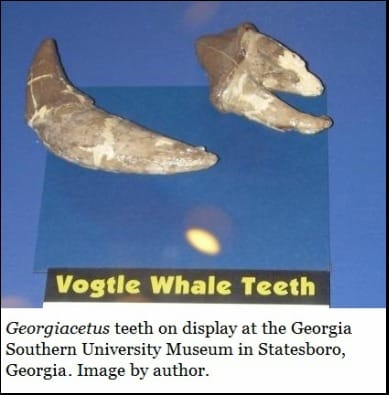

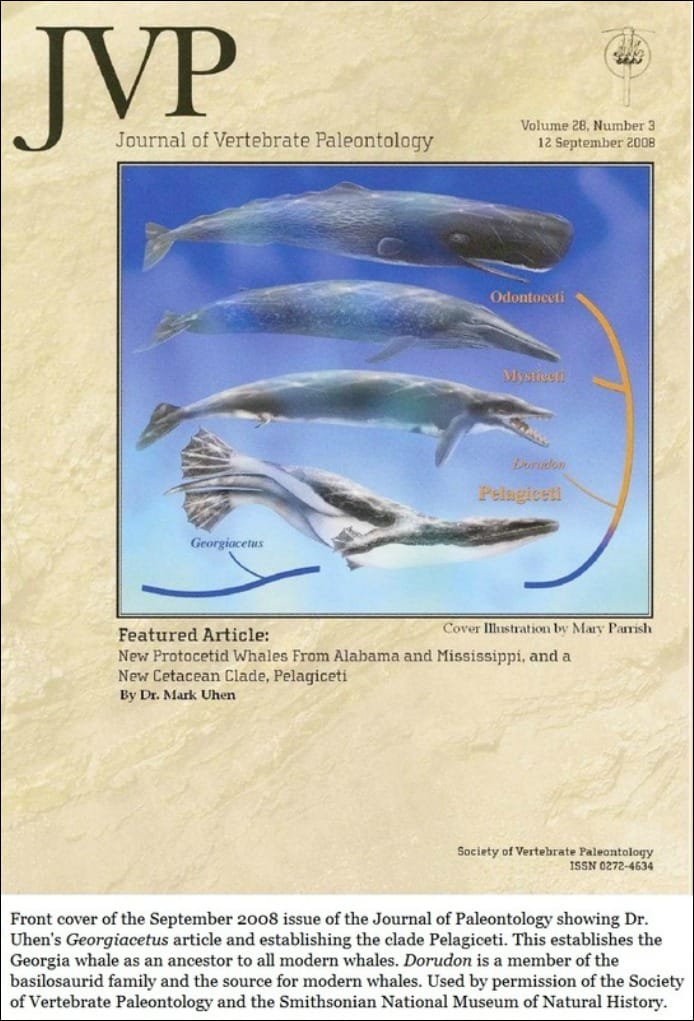

The basilosaurids were the descendants of Georgiacetus vogtlensis, the Georgia whale, also known as the Vogtle whale. The teeth clearly show close kinship betwwen Georgiacetus & the basilosaurids. (7,8)

Georgiacetus's fossils were discovered in 1983 during the original construction of the Southern Company’s nuclear power Plant Vogtle near Augusta, Georgia.

Georgiacetus lived 40 million years ago, say six million years before me. Its fossils have also been found in from Mississippi & Alabama.

The basilosaurids were the descendants of Georgiacetus vogtlensis, the Georgia whale, also known as the Vogtle whale. The teeth clearly show close kinship betwwen Georgiacetus & the basilosaurids. (7,8)

Georgiacetus's fossils were discovered in 1983 during the original construction of the Southern Company’s nuclear power Plant Vogtle near Augusta, Georgia.

Georgiacetus lived 40 million years ago, say six million years before me. Its fossils have also been found in from Mississippi & Alabama.

Since no tail material was found with the main Plant Vogtle mass we can only estimate its size, but the skull was nearly a meter long, so it’s hard to imagine a live animal less than 3 or 4 meters long.

The skull was a simplified version of the later basilosaurid skull. This skull, and pelvis arrangement, shows that Georgiacetus was the ancestor to the basilosaurids, and the basilosaurids are the ancestors to all modern whales. (7)

The skull was a simplified version of the later basilosaurid skull. This skull, and pelvis arrangement, shows that Georgiacetus was the ancestor to the basilosaurids, and the basilosaurids are the ancestors to all modern whales. (7)

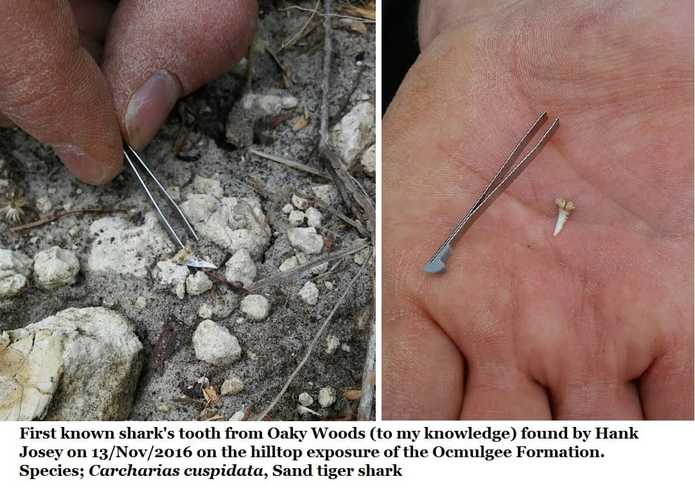

There were sharks too in these waters; great whites, requiem sharks, hammerheads, makos and even whale sharks are known from middle Georgia sediments of this time. Eagle rays, sting rays and sawfish are also recorded. (11, 10) All of these were marine hunters were feeding on hordes of prey; large and small.

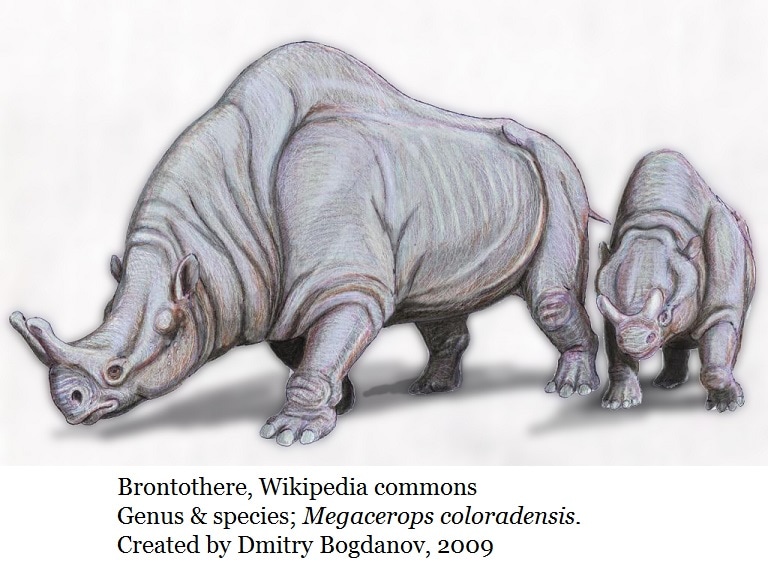

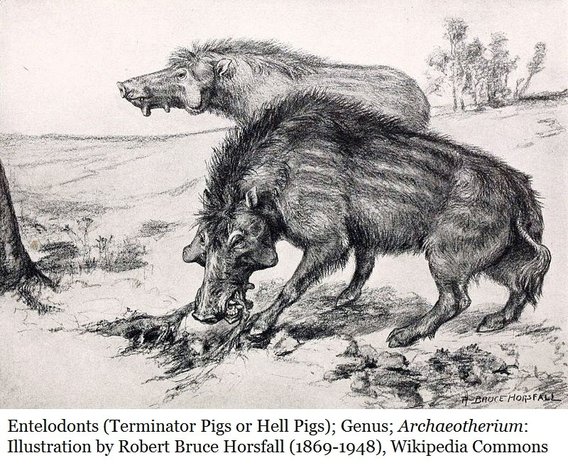

In my day the banks of the nearby paleo-Ocmulgee River knew many turtles and large snakes. (12,13) There were brontotheres (14) and entelodonts (15); as well as the prey and plants they all fed on.

This was middle Georgia, 34 million years ago; long before anything resembling humans walked the already ancient Earth.

When I lived in that shallow sea there was not a single stone tool or dugout canoe in all the world. Not a single word had yet been spoken. Early primates existed, but they were small, arboreal and lemur-like in my day.

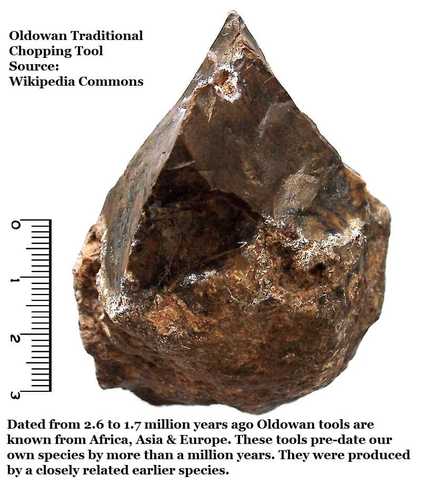

The first great apes were still 23 million years in the future. The first upright great ape was 26 million years in the future. The first stone tools didn’t appear until 30 million years after I died.

This was middle Georgia, 34 million years ago; long before anything resembling humans walked the already ancient Earth.

When I lived in that shallow sea there was not a single stone tool or dugout canoe in all the world. Not a single word had yet been spoken. Early primates existed, but they were small, arboreal and lemur-like in my day.

The first great apes were still 23 million years in the future. The first upright great ape was 26 million years in the future. The first stone tools didn’t appear until 30 million years after I died.

Those oldest stone tools; primitive Oldowan tools are only 2.6 million years old, but they weren’t made by your people, they were shaped by the hands of older species closely related to, but distinct from modern humans.

Your species; Homo sapiens sapiens only emerged about 200,000 years ago.

Primitive written language can be traced to at least 3,000 years ago, that was the beginning of widely shared knowledge.

Your species; Homo sapiens sapiens only emerged about 200,000 years ago.

Primitive written language can be traced to at least 3,000 years ago, that was the beginning of widely shared knowledge.

The study of paleontology as a valid science used understand the distant past only began about 238 years ago with the book Epochs of Nature by Georges Buffon (The Father of Natural History) which was published in 1778.

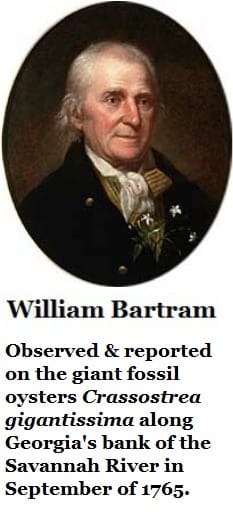

In 1765 John and William Bartram visited Shell Bluff, Georgia along the Savannah River and collected the oyster fossil Crassostrea gigantissima; they recorded these fossils as a “curious phenomenon”. (16)

It is an irony for Georgians that the earliest paleontological observations from Georgia predated the birth of paleontology as a science.

In 1765 John and William Bartram visited Shell Bluff, Georgia along the Savannah River and collected the oyster fossil Crassostrea gigantissima; they recorded these fossils as a “curious phenomenon”. (16)

It is an irony for Georgians that the earliest paleontological observations from Georgia predated the birth of paleontology as a science.

Autumn storms finally weathered me out of the rocks I’d known for so long, setting me free and washing me, downhill into a shallow, rain-fed stream.

When the amateur paleontologist found me a winter drought had emptied the stream and I rested, upright, among the rubble of weathered rock and leaf litter. Just as I'm seen in the picture.

When the amateur paleontologist found me a winter drought had emptied the stream and I rested, upright, among the rubble of weathered rock and leaf litter. Just as I'm seen in the picture.

He took these pics with his phone.

He used this picture, and others, to secure written permission from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to legally collect fossils from these hills for research purposes.

The problem was simple. The Georgia Geological Survey which had existed continuously since 1890 had been “abolished” in 2004 and it’s researchers had scattered to the winds.

The amateur’s first crack at research permission defeated him, bureaucracies resists change, but he’s a butt-headed old coot and kept at it.

He used this picture, and others, to secure written permission from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to legally collect fossils from these hills for research purposes.

The problem was simple. The Georgia Geological Survey which had existed continuously since 1890 had been “abolished” in 2004 and it’s researchers had scattered to the winds.

The amateur’s first crack at research permission defeated him, bureaucracies resists change, but he’s a butt-headed old coot and kept at it.

It took a year, but finally a letter found Don McGowan, Regional Operations Manager (Game Management) of the Wildlife Resource Division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Don called the amateur and they spoke at length. It was then that McGowan agreed to assist. He asked for a short proposal and advised on it’s content. He required professional and/or academic support, but since the amateur was well known by many of Georgia's professional paleontologist that didn’t prove to be a problem.

McGowan then personally submitted the proposal to the Commissioner’s Office of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. He even followed-up and corrected the error which got the original submission overlooked.

When the proposal was approved, it was McGowan who contacted the amateur. The amatuer's co-workers laughed at his “dance of joy” from the news.

Don called the amateur and they spoke at length. It was then that McGowan agreed to assist. He asked for a short proposal and advised on it’s content. He required professional and/or academic support, but since the amateur was well known by many of Georgia's professional paleontologist that didn’t prove to be a problem.

McGowan then personally submitted the proposal to the Commissioner’s Office of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. He even followed-up and corrected the error which got the original submission overlooked.

When the proposal was approved, it was McGowan who contacted the amateur. The amatuer's co-workers laughed at his “dance of joy” from the news.

The amateur researcher has never had a day of college but now enjoys the support of two respected universities in two states.

He’s ready to tackle the mysteries of Oaky Woods, to correct errors of the past and create new science for Georgia’s future.

He’ll come back to collect me. I won’t be lost to time. Rather, I’ll become a research specimen.

I’ll be reviewed by Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern in Americus.

When Dr. Carter retires I’ll be permanantly stored in the research collections of Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainsville.

I'll be under the care of Dr. Roger Portell, their highly respected invertebrate paleontologist.

Sadly, no Georgia university or natural history museum would accept me for permanent housing as part of their research collection.

I will be well cared for in Florida and rest among many of my relatives.

But I alone will be the Periarchuis quinquefarius from Oaky Woods’ Tobacco Road Sand/Ocmulgee Formation interfinger. A single sand dollar representing a time in Georgia where a lost sea met lost barrier islands and lagoons.

A sand dollar that waited for 34 million years in the hills of Middle Georgia.

I'm a reminder, like so many fossils, that the Earth does not require humans, but humans indeed require the Earth.

I lived long, long before you humans. Life flourished, proliferated and diversified for hundreds of millions of years before the first stone tool or dugout canoe.

He’s ready to tackle the mysteries of Oaky Woods, to correct errors of the past and create new science for Georgia’s future.

He’ll come back to collect me. I won’t be lost to time. Rather, I’ll become a research specimen.

I’ll be reviewed by Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern in Americus.

When Dr. Carter retires I’ll be permanantly stored in the research collections of Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainsville.

I'll be under the care of Dr. Roger Portell, their highly respected invertebrate paleontologist.

Sadly, no Georgia university or natural history museum would accept me for permanent housing as part of their research collection.

I will be well cared for in Florida and rest among many of my relatives.

But I alone will be the Periarchuis quinquefarius from Oaky Woods’ Tobacco Road Sand/Ocmulgee Formation interfinger. A single sand dollar representing a time in Georgia where a lost sea met lost barrier islands and lagoons.

A sand dollar that waited for 34 million years in the hills of Middle Georgia.

I'm a reminder, like so many fossils, that the Earth does not require humans, but humans indeed require the Earth.

I lived long, long before you humans. Life flourished, proliferated and diversified for hundreds of millions of years before the first stone tool or dugout canoe.

References

(1) Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central & Eastern Georgia; Paul F. Huddlestun & John H. Hetrick; Bulletin 95, Georgia Geological Survey, 1986.

(2) Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States; C. Wythe Cooke, Geological Survey Professional Paper 321, US Department of the Interior, 1959.

(3) The Oligocene, A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; Paul F. Huddlestun, Bulletin 105. Georgia Geologic Survey, 1993.

(4) Short Contributions to the Geology of Georgia; Bulletin 93, Stratigraphy of the Tobacco Road Sand – A New Formation, Pg. 56, Paul F. Huddlestun & John H. Hetrick, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1978.

(5) Paleoecology and Paleontology of an Extensive Rhodolith facies from the Lower Oligocene of Southe Georgia and North Florida; J.P. Manker & Burt Carter. Society for Economic Paleontologists & Mineralogist (Now the Society of Sedimentary Geology) Published in Palaios, 1987, Vol.2, pg.181-188.

(6) A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013.

(7) A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archeoceti) and associated Biota From Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Jr. Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.72, No.5, 1998. The Paleontological Society.

(8) New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

(9) Insights into the Locomotor Mode of the Ancient Whale Georgiacetus Based on Vertebral Morphology: Smith, Kathlyn M., Department of Geology and Geography, Georgia Southern University, Box 8149, Statesboro, GA 30460, Leverett, Kelsi Tate, Department of Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering, Missouri University of Science and Technology, 129 McNutt Hall, 1400 North Bishop, Rolla, MO 65409 and BEBEJ, Ryan M., Department of Biology, Calvin College, 1726 Knollcrest Circle SE, Grand Rapids, MI 49546. Presentation at the 65th annual meeting of the Geological Society of America, 1/April/2016, Southeastern Section, Fossil Vertebrates of the Southeastern United States.

(10) Stratigraphy, Paleontology and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia. Sam M. Pickering Jr. Bulletin 81. Georgia Geological Survey. 1970

(11) Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Dennis Parmley, David J. Cicimurri. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.61, Pgs 153-179, 2003. Georgia Academy of Sciences

(12) Diverse Turtle Fauna from the Late Eocene of Georgia Including the Oldest Records of Aquatic Testudinoids in Southeastern North America. Dennis Parmley, J. Howard Hutchinson and James F. Parham. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 43, No.3, Pgs. 343-350. 2006. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

(13) Palaeopheid Snakes from the late Eocene Hardie Mine Local fauna of Central Georgia. Dennis Parmley and Melanie DeVore. Southeastern Naturalist, Vol.4, No.4, pgs. 703-722. 2005.

(14) A brontothere tooth was recovered from Hardie Mine in Gordon Georgis, Clinchfield Formation, as reported in personal communication as an ongoing research topic by Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College Natural History Museum.

Seperatly; Amateur Robert (Bobby) Strange has also reported finding brontothere teeth in Late Eocene sediments.

(15) Dr. Michael Voorhies 1969, an entelodont tooth was collected by amateur Bill Christy and dinated to the University of Georgia collections a specimen #UGV-41. Originally believed to be a manatee tooth, researchers from the Smithsonian ID’d it as an entelodont. Since then several others have been found.

(16) Georgia Historical Marker, Shell Bluff, near the Waynesboro, Georgia Post Office.

The inscription reads; Shell Bluff on the Savannah River (15 miles northeast) has been famous since Indian days because of its outcrops of fossil shells including those of giant oysters. These lived in the Eocene sea that covered this part of Georgia some 50 million years ago. Shell Bluff has been visited and described by many famous travelers and geologists including Bartram in 1791, Vanuxem in 1828, Conrad in 1834, and Sir Charles Lyell in 1842. (Note; The stated age of 50 million years ago is incorrect and reflects the level of understand when these markers were conceived. Current estimates place these fossils at about 34+ million years old.)

(1) Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central & Eastern Georgia; Paul F. Huddlestun & John H. Hetrick; Bulletin 95, Georgia Geological Survey, 1986.

(2) Cenozoic Echinoids of the Eastern United States; C. Wythe Cooke, Geological Survey Professional Paper 321, US Department of the Interior, 1959.

(3) The Oligocene, A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; Paul F. Huddlestun, Bulletin 105. Georgia Geologic Survey, 1993.

(4) Short Contributions to the Geology of Georgia; Bulletin 93, Stratigraphy of the Tobacco Road Sand – A New Formation, Pg. 56, Paul F. Huddlestun & John H. Hetrick, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1978.

(5) Paleoecology and Paleontology of an Extensive Rhodolith facies from the Lower Oligocene of Southe Georgia and North Florida; J.P. Manker & Burt Carter. Society for Economic Paleontologists & Mineralogist (Now the Society of Sedimentary Geology) Published in Palaios, 1987, Vol.2, pg.181-188.

(6) A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013.

(7) A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archeoceti) and associated Biota From Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert, Jr. Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire. Journal of Paleontology, Vol.72, No.5, 1998. The Paleontological Society.

(8) New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

(9) Insights into the Locomotor Mode of the Ancient Whale Georgiacetus Based on Vertebral Morphology: Smith, Kathlyn M., Department of Geology and Geography, Georgia Southern University, Box 8149, Statesboro, GA 30460, Leverett, Kelsi Tate, Department of Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering, Missouri University of Science and Technology, 129 McNutt Hall, 1400 North Bishop, Rolla, MO 65409 and BEBEJ, Ryan M., Department of Biology, Calvin College, 1726 Knollcrest Circle SE, Grand Rapids, MI 49546. Presentation at the 65th annual meeting of the Geological Society of America, 1/April/2016, Southeastern Section, Fossil Vertebrates of the Southeastern United States.

(10) Stratigraphy, Paleontology and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia. Sam M. Pickering Jr. Bulletin 81. Georgia Geological Survey. 1970

(11) Late Eocene Sharks of the Hardie Mine Local Fauna of Wilkinson County, Georgia. Dennis Parmley, David J. Cicimurri. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.61, Pgs 153-179, 2003. Georgia Academy of Sciences

(12) Diverse Turtle Fauna from the Late Eocene of Georgia Including the Oldest Records of Aquatic Testudinoids in Southeastern North America. Dennis Parmley, J. Howard Hutchinson and James F. Parham. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 43, No.3, Pgs. 343-350. 2006. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

(13) Palaeopheid Snakes from the late Eocene Hardie Mine Local fauna of Central Georgia. Dennis Parmley and Melanie DeVore. Southeastern Naturalist, Vol.4, No.4, pgs. 703-722. 2005.

(14) A brontothere tooth was recovered from Hardie Mine in Gordon Georgis, Clinchfield Formation, as reported in personal communication as an ongoing research topic by Dr. Dennis Parmley at Georgia College Natural History Museum.

Seperatly; Amateur Robert (Bobby) Strange has also reported finding brontothere teeth in Late Eocene sediments.

(15) Dr. Michael Voorhies 1969, an entelodont tooth was collected by amateur Bill Christy and dinated to the University of Georgia collections a specimen #UGV-41. Originally believed to be a manatee tooth, researchers from the Smithsonian ID’d it as an entelodont. Since then several others have been found.

(16) Georgia Historical Marker, Shell Bluff, near the Waynesboro, Georgia Post Office.

The inscription reads; Shell Bluff on the Savannah River (15 miles northeast) has been famous since Indian days because of its outcrops of fossil shells including those of giant oysters. These lived in the Eocene sea that covered this part of Georgia some 50 million years ago. Shell Bluff has been visited and described by many famous travelers and geologists including Bartram in 1791, Vanuxem in 1828, Conrad in 1834, and Sir Charles Lyell in 1842. (Note; The stated age of 50 million years ago is incorrect and reflects the level of understand when these markers were conceived. Current estimates place these fossils at about 34+ million years old.)