19: Pliocene Epoch;

5.3 to 2.5 million years ago

By Thomas Thurman

During the Pliocene major global sea level changes continued with the cycle of ice ages becoming fully established.

These are the glacial periods, a “glacial” or “glacial period” is a single cycle from minimal to maximum glaciation; or one glacial stage event and one interglacial stage event.

· A glacial stage is when glaciers are dominant and so much water is trapped in ice that sea levels recede.

· An interglacial stage is the opposite; the climate warms, glaciers recede and release their water into their seas which causes sea levels to advance.

This pulse of glacial and interglacial stages is something relatively new in Earth’s history beginning about nine million years ago. There are many things which contributed to repetitious ice ages; fluctuations in Earth’s orbit, fluctuations in solar output, small changes in how much solar heat is trapped or reflected, the change in global ocean currents when Antarctica moved to the South Pole.

This shifting of Antarctica to the South Pole is critical; it permanently established a circumpolar, cold water current, in the Southern Hemisphere and drove down global temperatures.

Generally speaking, the global climate continued a trend towards the modern climate; cooler, drier, and with distinct seasons. The polar ice caps began to become permanent and tropical climates were restricted to the equatorial areas.

This climate allowed grasses to extend worldwide except for cold Antarctica. Deciduous trees (which shed their leaves during winter dormancy) proliferated and northern latitudes were dominated by conifers and tundra.

The lands and seas were mostly inhabited by modern types of animals. The earliest hominids, the australopithecines, had emerged in Africa. They weren’t human, but in time our own genus and eventually species would emerge from their line.

Raising the Isthmus of Panama

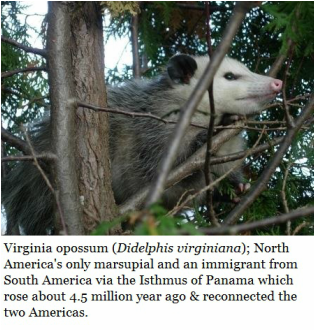

Of importance to North America and Georgia was volcanic activity which caused the Isthmus of Panama to rise and connect North and South America. For tens of millions of years these had been independent continents, each with their own distinct populations.

The familiar placental mammals ruled North America.

Marsupials, in amazing diversity, ruled South America. With the opening of the land bridge the Great American Exchange began.

Georgia’s modern marsupial, the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), is a result of that land bridge; its ancestor’s emerged in South American and expanded their range to southeastern North America across that land bridge. This was the first mass exchange of land species between North and South America since the Cretaceous Period.

There are several other species which successfully migrated northward and established themselves in North America, however for the most part the South American marsupials did not fare well against the North American placental mammals.

Of importance to North America and Georgia was volcanic activity which caused the Isthmus of Panama to rise and connect North and South America. For tens of millions of years these had been independent continents, each with their own distinct populations.

The familiar placental mammals ruled North America.

Marsupials, in amazing diversity, ruled South America. With the opening of the land bridge the Great American Exchange began.

Georgia’s modern marsupial, the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), is a result of that land bridge; its ancestor’s emerged in South American and expanded their range to southeastern North America across that land bridge. This was the first mass exchange of land species between North and South America since the Cretaceous Period.

There are several other species which successfully migrated northward and established themselves in North America, however for the most part the South American marsupials did not fare well against the North American placental mammals.

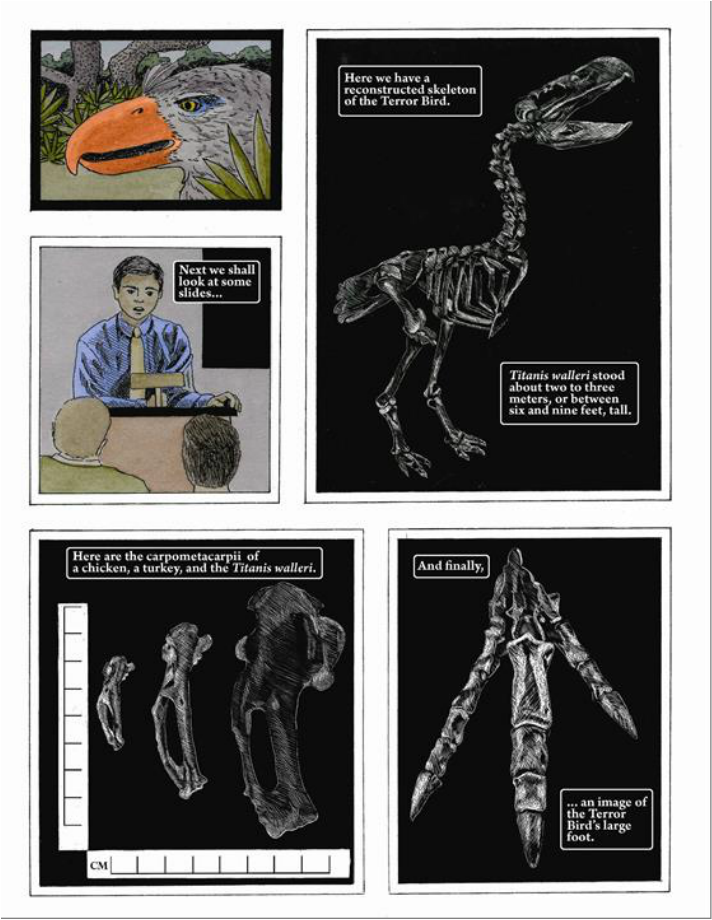

Even in South America, the invading placental mammals displaced native marsupials and in most cases probably initiated their extinction by out-competing them for available food sources. There are some notable exceptions, like the terror birds

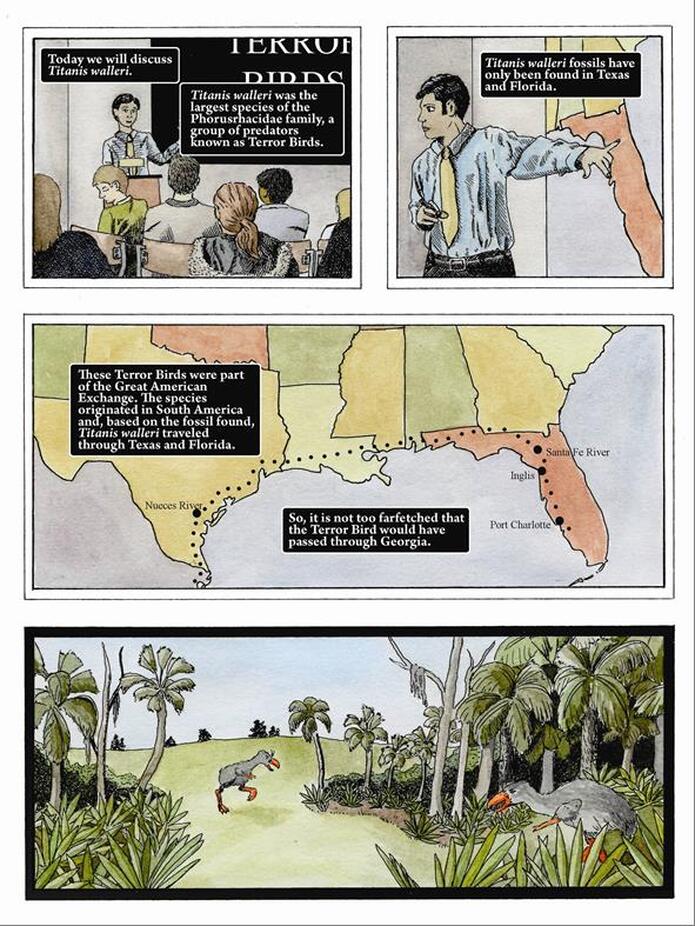

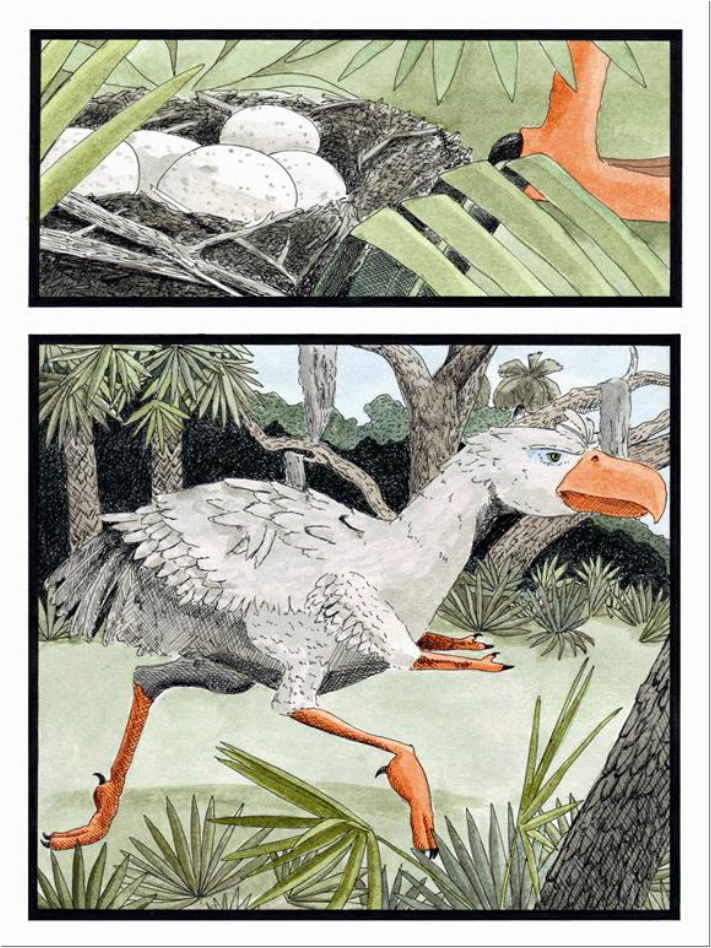

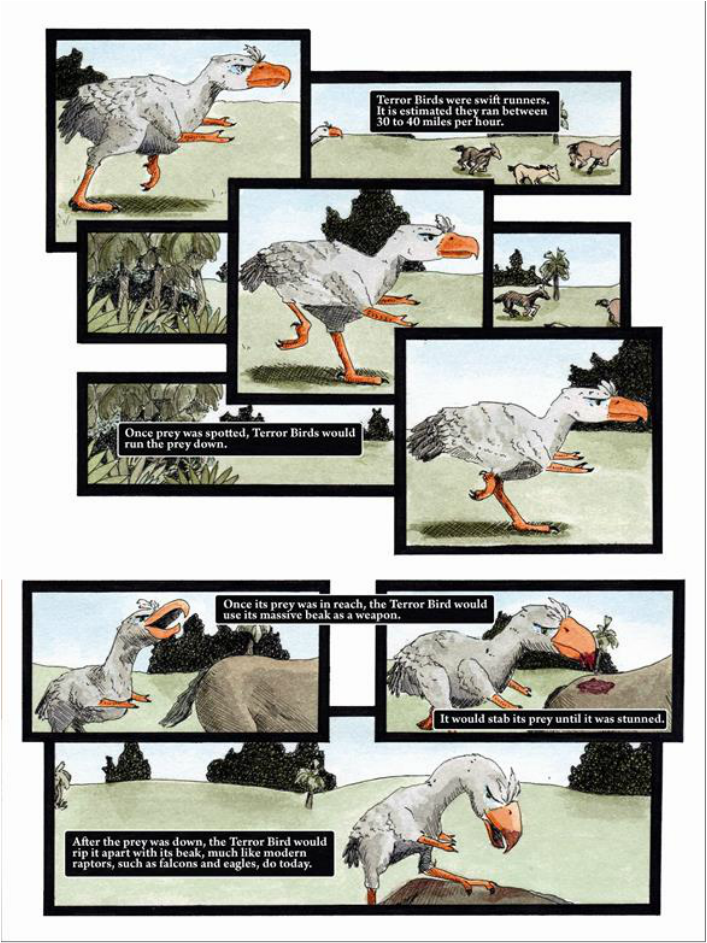

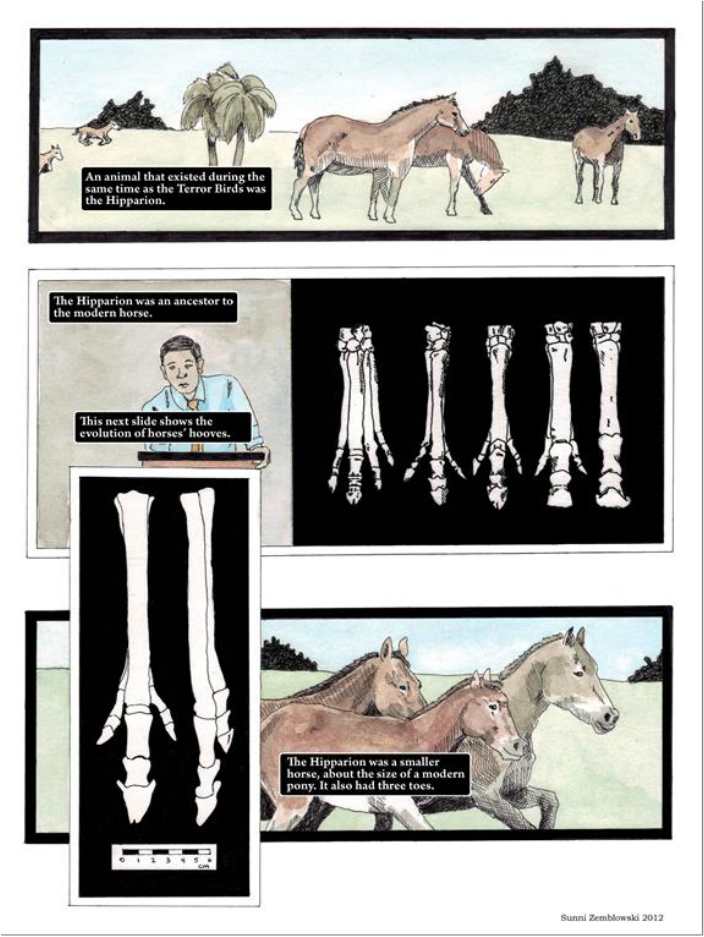

We have Sunni Zemblowski to thank for these images of a classroom lecture over Titanis walleri and the Hipparion Horse, though T. Walleri has not been show in Georgia it likely occurred. The Hipparion horse is a different matter, it is well known from Georgia.

We have Sunni Zemblowski to thank for these images of a classroom lecture over Titanis walleri and the Hipparion Horse, though T. Walleri has not been show in Georgia it likely occurred. The Hipparion horse is a different matter, it is well known from Georgia.

Titanis walleri; The Terror Birds

Another successful invader from South America was the terror birds (family; Phorusrhacidae). The largest of these, Titanis walleri, is the only species known to occur in North America and has been found in both Texas and Florida.

It has not been reported from Georgia, but since it couldn’t fly it’s hard to imagine it walking from Texas to Florida without crossing or entering Georgia at some point. Of course sea levels were frequently different; the path it followed may well be submerged today.

T. walleri met extinction about 1.8 million years ago.

Dr. Bob Chandler at Georgia College Natural History Museum, and lead author on the Auk paper we reviewed, is a nationally recognized leader in bird fossils and an expert on the terror birds, especially Titanis walleri. His research has been featured in Discovery magazine and on television.

In life, T. walleri stood more than 8 feet tall and weighed about 330 pounds. It was a runner and research has suggested speeds of 40 miles per hour might have been possible.

Another successful invader from South America was the terror birds (family; Phorusrhacidae). The largest of these, Titanis walleri, is the only species known to occur in North America and has been found in both Texas and Florida.

It has not been reported from Georgia, but since it couldn’t fly it’s hard to imagine it walking from Texas to Florida without crossing or entering Georgia at some point. Of course sea levels were frequently different; the path it followed may well be submerged today.

T. walleri met extinction about 1.8 million years ago.

Dr. Bob Chandler at Georgia College Natural History Museum, and lead author on the Auk paper we reviewed, is a nationally recognized leader in bird fossils and an expert on the terror birds, especially Titanis walleri. His research has been featured in Discovery magazine and on television.

In life, T. walleri stood more than 8 feet tall and weighed about 330 pounds. It was a runner and research has suggested speeds of 40 miles per hour might have been possible.

Chandler began finding new material from T. walleri in Florida’s Santa Fe River and started serious recovery efforts. Of particular importance were bones from T. walleri’s former wing which shows that evolution had restructured the limb. Researchers had expected to find atrophied wings like an ostrich’s; instead they found that T. walleri’s wing had re-evolved claws with an opposable digit.

This was not an evolutionary re-run of the old dinosaur claw but an evolutionary reworking of the bird’s wing to a new purpose. The wing bones were no longer hollow like a bird’s, but solid, and wrist bones were reworked and refused. This “wing’ had become a useful arm with a wrist and “hand” which would have been held in front of the bird with palms facing inward, allowing it to manipulated food and perhaps restrain struggling prey.

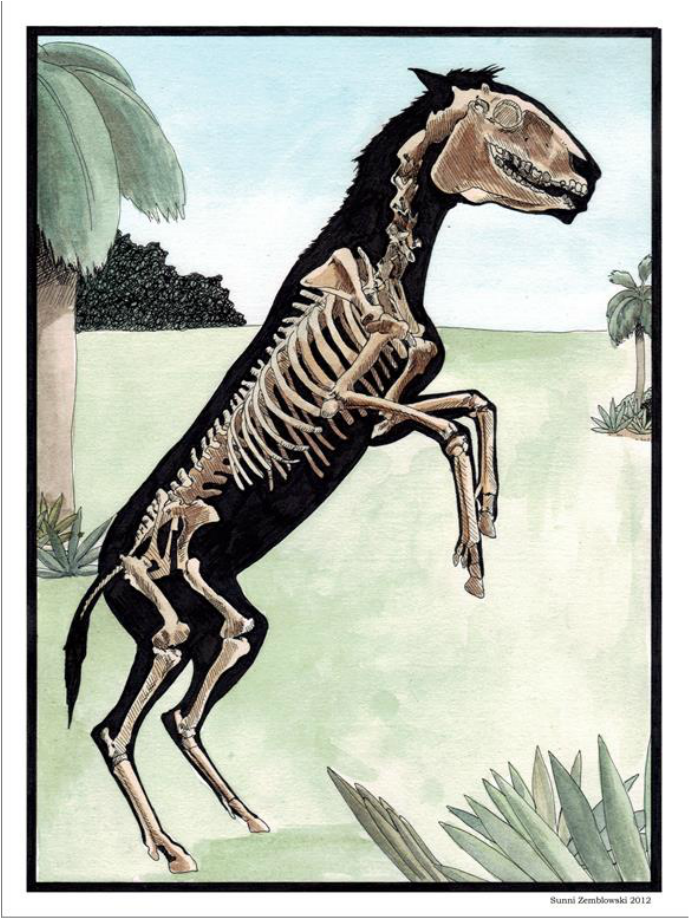

Hipparion Horse

Hulbert and Pratt also recovered horse fossils from the extinct Hipparion genus during their coastal Georgia research.

Hulbert and Pratt also recovered horse fossils from the extinct Hipparion genus during their coastal Georgia research.

The Hipparion genus was a smallish, three toed horse that emerged during the Miocene and endured through the Pleistocene. It is known from Asia, Europe, Africa and North America. North American ranges are known from Florida to California and into Canada. It had three toes per foot but the two outer toes did not reach the ground and like modern horses this genus walked on a single toe. This was a very lightly built grazing animal found on grasslands only reaching about 4.5 feet at the shoulder. Weights have been estimated between 140 pound and 260 pounds for adults.

Adaptations towards running were already well established.

Adaptations towards running were already well established.

Northwestern Savannah:

Richard Hulbert and Ann Pratt reported the presence of a megalodon, Scaldicetus and Hipparion fossil, they noted several other Miocene and/or Pliocene finds mixed with the Pleistocene material.

The pre-Pleistocene fossils had eroded out of older, upstream beds. They reported that in these deposits the Pleistocene vertebrate material was actually less common than fossils from older specimens and usually consisted worn isolated teeth, teeth fragments and robust skeletal elements.

Crocodilians

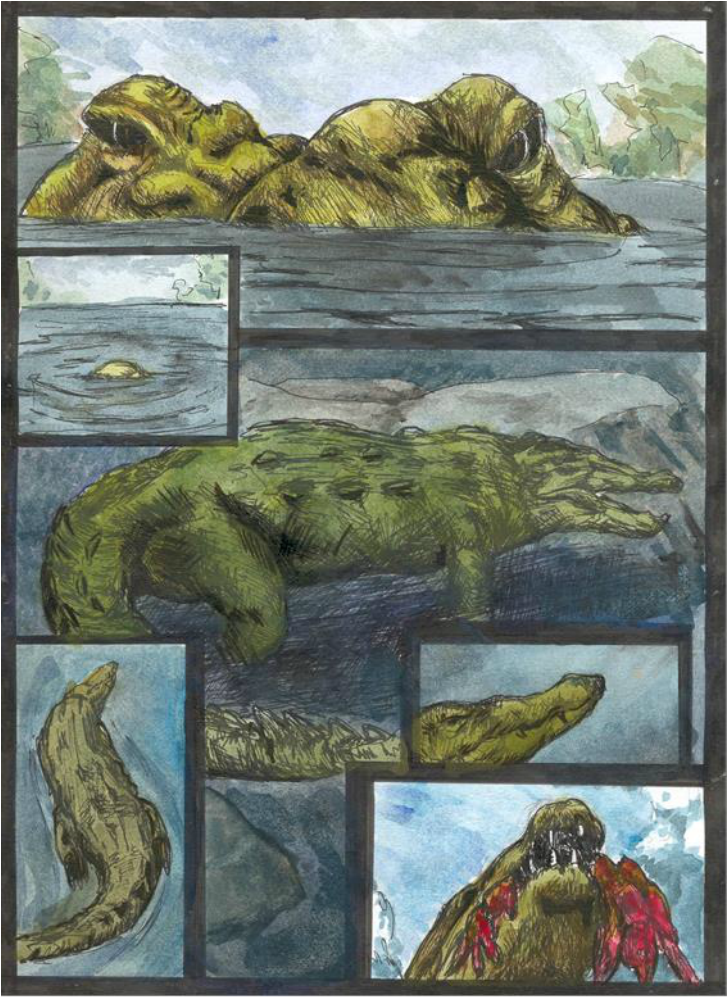

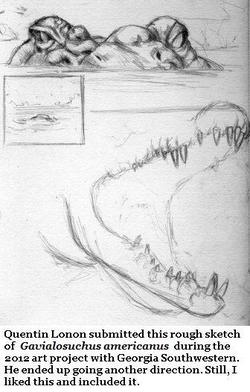

They identified fossils from Gavialosuchus americanus; a large, extinct coastal crocodile which reached estimated lengths of 32 feet.

Note; Hank Josey forwarded an 24/Oct/2017 email he received over Gavialsuchus from Christopher Brochu at the University of Iowa.

"Thecachampsa and Gavialosuchus were once thought to be synonymous, but they're not - Gavialosuchus is known with certainty only from Austria. All North American "Gavialosuchus" are Thecachampsa.

In my view, there are three known species - T. carolinense, T. antiqua, and T. americana."

Christopher A. Brochu

Professor & Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences

Chair, CLAS Faculty Assembly

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA 52242 USA

It emerged into the fossil record during the late Miocene and endured to the Pliocene epoch. It is thought to have preferred estuarine environments, where rivers meet the sea.

The genus is known from the Southeast USA, another species of the genus occurs in Europe.

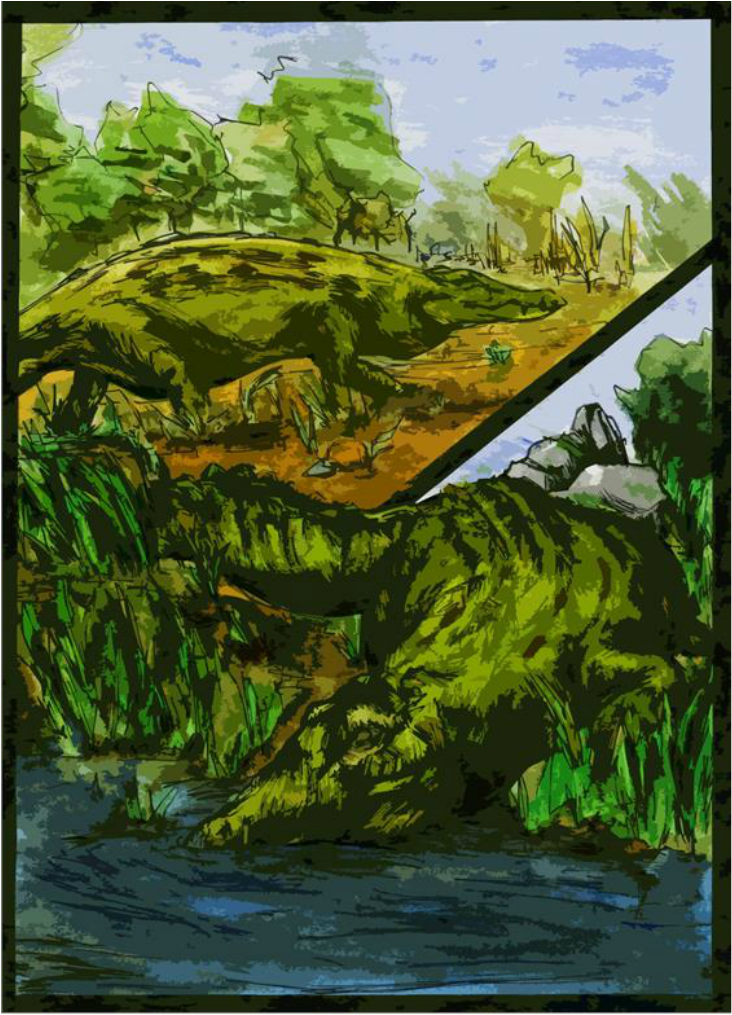

We have Quentin Lonon to thank for these two color images of Thecacampsa americanus during a successful hunt. He created them during the 2012 Georgia Southwestern art project.

Georgia has a long history with the order Crocodilia which includes the genus Deinosuchus which hunted Georgia 77 million years ago, Thecachampsa , which hunted Georgia 6 million years ago and the modern Alligator mississippiensis which hunts Georgia today. Thecachampsa

They identified fossils from Gavialosuchus americanus; a large, extinct coastal crocodile which reached estimated lengths of 32 feet.

Note; Hank Josey forwarded an 24/Oct/2017 email he received over Gavialsuchus from Christopher Brochu at the University of Iowa.

"Thecachampsa and Gavialosuchus were once thought to be synonymous, but they're not - Gavialosuchus is known with certainty only from Austria. All North American "Gavialosuchus" are Thecachampsa.

In my view, there are three known species - T. carolinense, T. antiqua, and T. americana."

Christopher A. Brochu

Professor & Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences

Chair, CLAS Faculty Assembly

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA 52242 USA

It emerged into the fossil record during the late Miocene and endured to the Pliocene epoch. It is thought to have preferred estuarine environments, where rivers meet the sea.

The genus is known from the Southeast USA, another species of the genus occurs in Europe.

We have Quentin Lonon to thank for these two color images of Thecacampsa americanus during a successful hunt. He created them during the 2012 Georgia Southwestern art project.

Georgia has a long history with the order Crocodilia which includes the genus Deinosuchus which hunted Georgia 77 million years ago, Thecachampsa , which hunted Georgia 6 million years ago and the modern Alligator mississippiensis which hunts Georgia today. Thecachampsa

Dugong

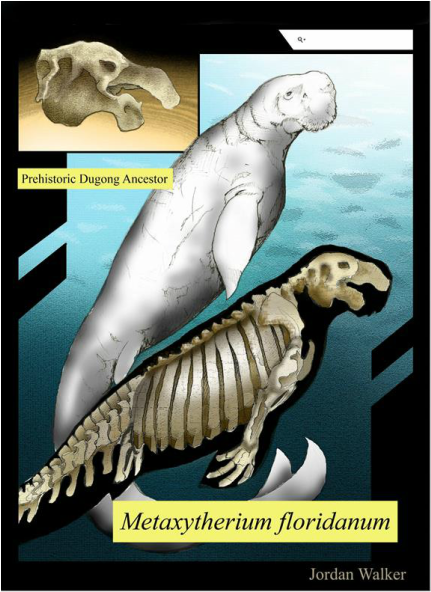

Hulbert and Pratt also identified a Metaxytherium; an extinct genus of dugong (Order Sirenia; related to manatees) that endured in the Mediterranean until the Pilocene Epoch (5.3 to 2.5 million years ago) but by the end of the Miocene Epoch (23.3 – 5.3 million years ago) it is absent in the Americas.

This image of Metaxytherium floridanum was created during the 2012 project by Jordan Walker, whose work brings many animals to life in these pages. Hulbert and Pratt did not record a species in their research, only the genus Metaxytherium.

Jordan illustrated this animal as a reference. This animal would have possessed flukes closer to those of a modern whale than a modern manatee. There is one error on this image; Metaxytherium would not have possessed rear flippers. I want to thank Dr. Daryl Domning, an expert in siren fossils at Howard University in Washington DC for advising us that “the closest living analogue was Dugong dugon”; this gave Jordan a starting point.

No members of this particular genre survive. The order of Sirenia emerged during the Eocene epoch and achieved modest diversification during the Oligocene and Miocene, but due to geological climate change, oceanographic change and human interference their diversity declined and only two genera and four species remain in modern times.

In life Metaxytherium was probably 12 to 15 feet long.

Metaxytherium would have lived and quietly fed along the same estuarine environments hunted by the crocodilian Gavialosuchus americanuson and the 30 foot predator would have been a serious threat to our dugong. Metaxytherium was not a small siren, but it would have been no match for a 30 foot Gavialosuchus.

Mastodons

Mastodons, distant members of the elephant family, are also known from Georgia’s Pliocene deposits, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History houses a mastodon tooth collected in 1927 by I. R. Tompkins and assigned to the Early Pliocene Epoch; we’ll look more closely at mastodons later; the record does not assign a species or county for the find.

Hulbert and Pratt also identified a Metaxytherium; an extinct genus of dugong (Order Sirenia; related to manatees) that endured in the Mediterranean until the Pilocene Epoch (5.3 to 2.5 million years ago) but by the end of the Miocene Epoch (23.3 – 5.3 million years ago) it is absent in the Americas.

This image of Metaxytherium floridanum was created during the 2012 project by Jordan Walker, whose work brings many animals to life in these pages. Hulbert and Pratt did not record a species in their research, only the genus Metaxytherium.

Jordan illustrated this animal as a reference. This animal would have possessed flukes closer to those of a modern whale than a modern manatee. There is one error on this image; Metaxytherium would not have possessed rear flippers. I want to thank Dr. Daryl Domning, an expert in siren fossils at Howard University in Washington DC for advising us that “the closest living analogue was Dugong dugon”; this gave Jordan a starting point.

No members of this particular genre survive. The order of Sirenia emerged during the Eocene epoch and achieved modest diversification during the Oligocene and Miocene, but due to geological climate change, oceanographic change and human interference their diversity declined and only two genera and four species remain in modern times.

In life Metaxytherium was probably 12 to 15 feet long.

Metaxytherium would have lived and quietly fed along the same estuarine environments hunted by the crocodilian Gavialosuchus americanuson and the 30 foot predator would have been a serious threat to our dugong. Metaxytherium was not a small siren, but it would have been no match for a 30 foot Gavialosuchus.

Mastodons

Mastodons, distant members of the elephant family, are also known from Georgia’s Pliocene deposits, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History houses a mastodon tooth collected in 1927 by I. R. Tompkins and assigned to the Early Pliocene Epoch; we’ll look more closely at mastodons later; the record does not assign a species or county for the find.

sedimentys

A Georgia Rhino

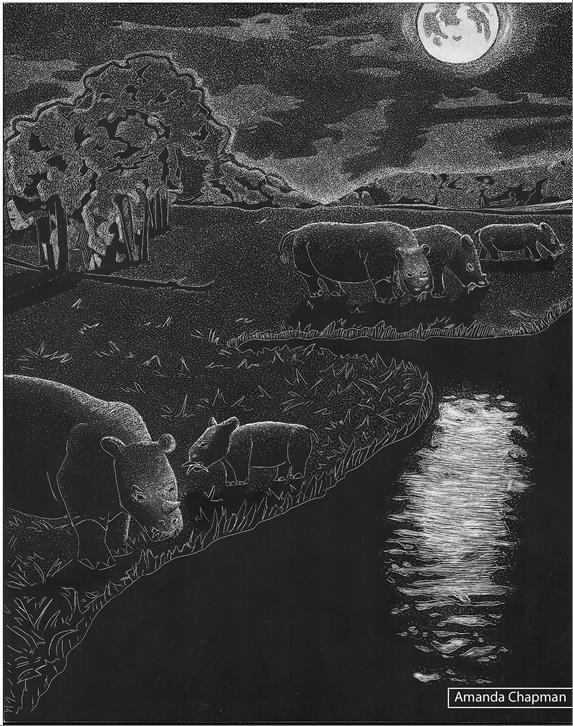

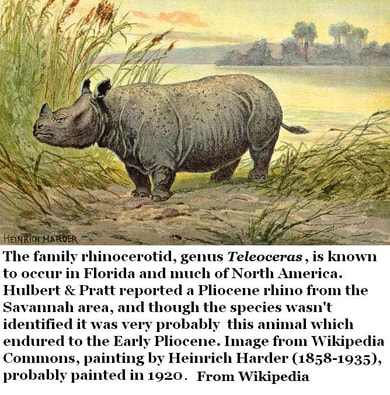

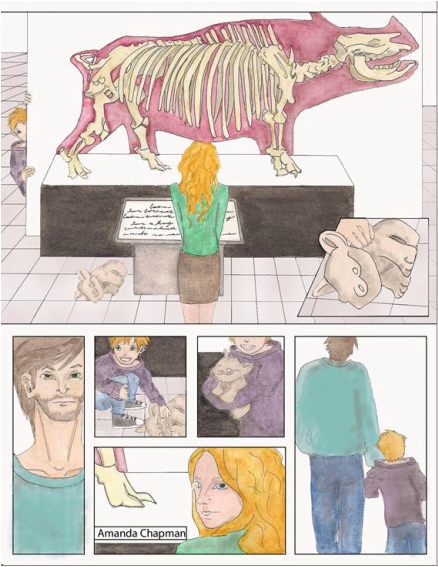

Hulbert and Pratt identified a Rhinocerotid in Georgia’s coastal sediments; this is the family of rhinoceroses which emerged in the Eocene, and developed into animals ranging from dog sized to the largest terrestrial animals ever to walk the Earth (see genus; Paraceratherium).

Modern rhinos are believed to have dispersed from Asia by the Miocene. The paper does not further describe exactly what specimen was recovered or where it might fit in the Rhinocerotid family. However, in 1957 Vernon Hurst explained that the genus Teleoceras was known from Florida and would likely occur in Georgia.

Teleoceras is a genus of grazing, heavy bodied, short legged rhinos with a single small horn. They emerged during the Miocene epoch and lasted through to the early Pliocene about 5 million years ago. They are very well known from Ashfall Fossil Beds of Nebraska.

Note; Teleoceras is known from Georgia's Miocene sediments, specifically in Echols County.

Amanda Chapman created these pages showing Teleoceras, first as a museum display (not unlike the one at the Smithsonian) then as a group feeding by the moonlight beside a waterway. I like the museum images of the child reclaiming the lost rhino toy while visiting the museum with parents. I hate to say that I’ve seen my 3 year old with that same impish grin.

A Georgia Rhino

Hulbert and Pratt identified a Rhinocerotid in Georgia’s coastal sediments; this is the family of rhinoceroses which emerged in the Eocene, and developed into animals ranging from dog sized to the largest terrestrial animals ever to walk the Earth (see genus; Paraceratherium).

Modern rhinos are believed to have dispersed from Asia by the Miocene. The paper does not further describe exactly what specimen was recovered or where it might fit in the Rhinocerotid family. However, in 1957 Vernon Hurst explained that the genus Teleoceras was known from Florida and would likely occur in Georgia.

Teleoceras is a genus of grazing, heavy bodied, short legged rhinos with a single small horn. They emerged during the Miocene epoch and lasted through to the early Pliocene about 5 million years ago. They are very well known from Ashfall Fossil Beds of Nebraska.

Note; Teleoceras is known from Georgia's Miocene sediments, specifically in Echols County.

Amanda Chapman created these pages showing Teleoceras, first as a museum display (not unlike the one at the Smithsonian) then as a group feeding by the moonlight beside a waterway. I like the museum images of the child reclaiming the lost rhino toy while visiting the museum with parents. I hate to say that I’ve seen my 3 year old with that same impish grin.

Nebraska Ashfall Beds

As a note, paleontologist Dr. Mike Voorhies, now a Professor Emeritus with the University of Nebraska is closely associated with the ash fall fossils beds of Nebraska and published a major paper on them in 1992. Dr. Voorhies was with the University of Georgia for many years and accidentally discovered Georgia’s first entelodont; he is also credited for naming the Clinchfield Formation of Central and East Georgia (Pickering 1970, Bulletin 81, pg7).

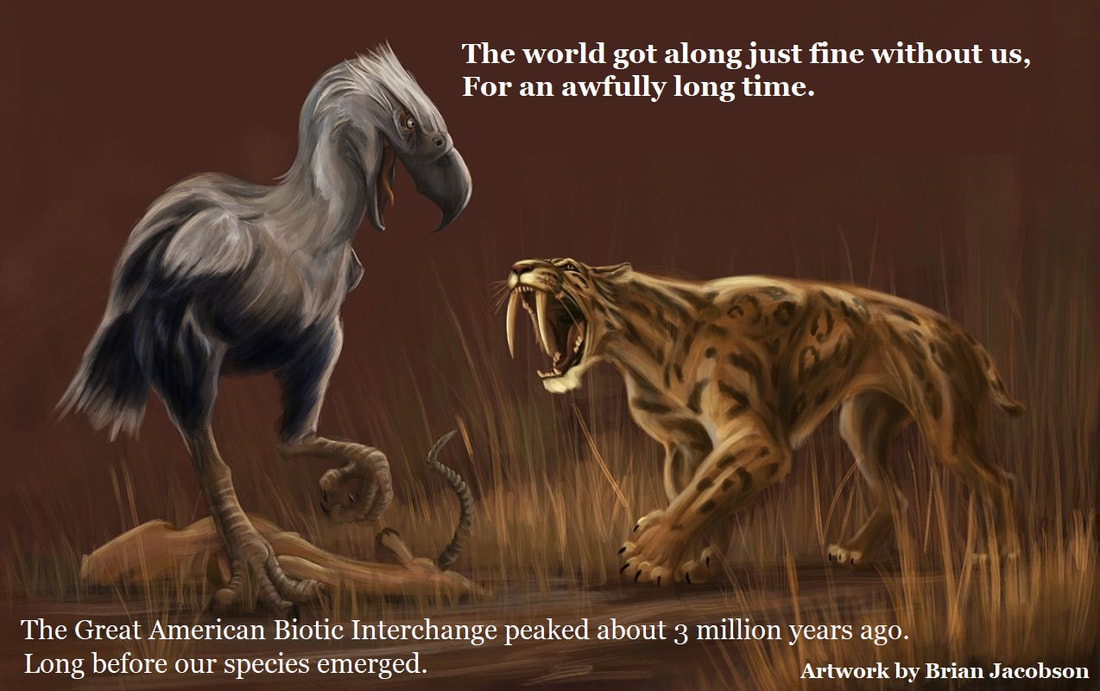

The Ashfall Beds of Nebraska deserve a bit more attention here, while Teleoceras was the most common find it was not alone in the beds. This is the story of a watering site which was buried under volcanic ash from the eruption of a super volcano in Idaho 12 million years ago. This volcano was nearly 1000 miles west of the Nebraska Ashfall beds. The environment was a grassland savannah with a warmer climate than Nebraska knows today. It likely took the animals a few days to die from lung failure caused by inhaling abrasive volcanic ash, young animals perished first, with adults following soon thereafter. Preservation in the soft ash was superb. There was some evidence of scavenging by predators, but only on a very small scale as most of the remains are articulated, with all of their bones in living positions. One mother and calf was found snout to snout. A pregnant female was found with the fetus preserved as well. This is tragic, but it happened 10 million years before the first human walked the Earth. It has given us a glimpse of that lost world with over 200 skeletons from 12 species represented. Bear in mind that the world got along just fine without us for most of its history. It needs our help today mostly because of what we have done in the past, and often continue to do.(50)

Finds of the Nebraska Ashfall Beds: (50)

Fossils from five horses were recovered:

Three toed relatives of Hipparion were found

Pseudhipparion gratum, Small 3-toed horse

Neohipparion affine, Slender 3-toed horse

Cormohipparion occidentale, Stout 3-toed horse

Single toed horses also occur

Protohippus simus, Slender one-toed horse

Pliohippus pernix, Stout 1-toed horse

Fossil from three species of camels were recovered:

Aepycamelus, Giraffe-like camel

Protolabis heterodontus, Llama-like camel

Procamelus grandis, Ancestral camel

Fossil from one saber toothed deer were found:

Longirostromeryx wellsi

Fossil from three species of dog were recovered:

Cynarctu, Raccoon Dog

Leptocyon, Fox-sized Dog

Bone-crushing Dog,

(Identified by scavenging evidence at this site)

Two species of turtle were recovered:

Hesperotestudo, Giant tortoise

(Also in Georgia’s Ice Age fossil record)

Sternotherus, Musk turtle or stinkpot

Two species of birds were identified:

Apatosagittarus terrenus, Secretary Bird

Balearica exigua, Crowned crane

These are interesting as they are all contemporaries of Teleoceras and it is entirely possible that some of them may one day be confirmed in the Southeast or Georgia

Many researchers believe that Teleoceras spent a great deal of time in the water. Weights for have been estimated to 2200 pounds with a length of 10 to 12 feet. The holotype for the genus came from Sheridan County, Nebraska and is dated to between 13.6 and 10.3 million years old. Other locations have produced fossils dated from 13 to 5 million years old, these locations include Nevada, Kansas, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Florida (multiple locations), California, Colorado and Mexico. It would take additional fossils to confirm the presence of Teleoceras in Georgia.

References:

Geologic Map of Georgia, 1976, Pickering, Georgia Geological Survey

North American Land Bridge; Wikipedia

Titanus walleri

Chandler, R.M. (1994). “The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida.” Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences, 36: 175-180.

Hipparion horse, Gavialosuchus americanus crocodilian, Metaxytherium Dugong, Rhinocerotid (Rhino); New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.

As a note, paleontologist Dr. Mike Voorhies, now a Professor Emeritus with the University of Nebraska is closely associated with the ash fall fossils beds of Nebraska and published a major paper on them in 1992. Dr. Voorhies was with the University of Georgia for many years and accidentally discovered Georgia’s first entelodont; he is also credited for naming the Clinchfield Formation of Central and East Georgia (Pickering 1970, Bulletin 81, pg7).

The Ashfall Beds of Nebraska deserve a bit more attention here, while Teleoceras was the most common find it was not alone in the beds. This is the story of a watering site which was buried under volcanic ash from the eruption of a super volcano in Idaho 12 million years ago. This volcano was nearly 1000 miles west of the Nebraska Ashfall beds. The environment was a grassland savannah with a warmer climate than Nebraska knows today. It likely took the animals a few days to die from lung failure caused by inhaling abrasive volcanic ash, young animals perished first, with adults following soon thereafter. Preservation in the soft ash was superb. There was some evidence of scavenging by predators, but only on a very small scale as most of the remains are articulated, with all of their bones in living positions. One mother and calf was found snout to snout. A pregnant female was found with the fetus preserved as well. This is tragic, but it happened 10 million years before the first human walked the Earth. It has given us a glimpse of that lost world with over 200 skeletons from 12 species represented. Bear in mind that the world got along just fine without us for most of its history. It needs our help today mostly because of what we have done in the past, and often continue to do.(50)

Finds of the Nebraska Ashfall Beds: (50)

Fossils from five horses were recovered:

Three toed relatives of Hipparion were found

Pseudhipparion gratum, Small 3-toed horse

Neohipparion affine, Slender 3-toed horse

Cormohipparion occidentale, Stout 3-toed horse

Single toed horses also occur

Protohippus simus, Slender one-toed horse

Pliohippus pernix, Stout 1-toed horse

Fossil from three species of camels were recovered:

Aepycamelus, Giraffe-like camel

Protolabis heterodontus, Llama-like camel

Procamelus grandis, Ancestral camel

Fossil from one saber toothed deer were found:

Longirostromeryx wellsi

Fossil from three species of dog were recovered:

Cynarctu, Raccoon Dog

Leptocyon, Fox-sized Dog

Bone-crushing Dog,

(Identified by scavenging evidence at this site)

Two species of turtle were recovered:

Hesperotestudo, Giant tortoise

(Also in Georgia’s Ice Age fossil record)

Sternotherus, Musk turtle or stinkpot

Two species of birds were identified:

Apatosagittarus terrenus, Secretary Bird

Balearica exigua, Crowned crane

These are interesting as they are all contemporaries of Teleoceras and it is entirely possible that some of them may one day be confirmed in the Southeast or Georgia

Many researchers believe that Teleoceras spent a great deal of time in the water. Weights for have been estimated to 2200 pounds with a length of 10 to 12 feet. The holotype for the genus came from Sheridan County, Nebraska and is dated to between 13.6 and 10.3 million years old. Other locations have produced fossils dated from 13 to 5 million years old, these locations include Nevada, Kansas, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Florida (multiple locations), California, Colorado and Mexico. It would take additional fossils to confirm the presence of Teleoceras in Georgia.

References:

Geologic Map of Georgia, 1976, Pickering, Georgia Geological Survey

North American Land Bridge; Wikipedia

Titanus walleri

Chandler, R.M. (1994). “The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida.” Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences, 36: 175-180.

Hipparion horse, Gavialosuchus americanus crocodilian, Metaxytherium Dugong, Rhinocerotid (Rhino); New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.