The Gordian Knot

of Georgia’s

Early Oligocene Sediments

By Thomas Thurman

Posted 29/May/2021

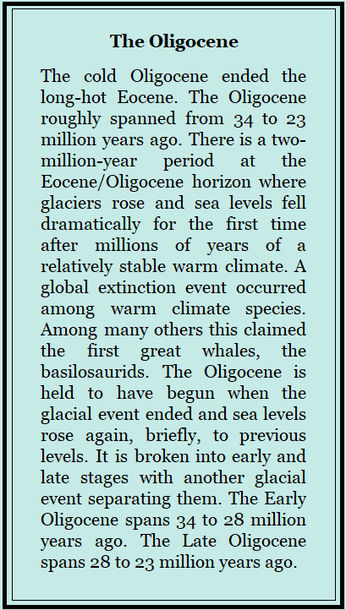

The Highly Variable Oligocene

Of Central Georgia’s Northern Coastal Plain

Of Central Georgia’s Northern Coastal Plain

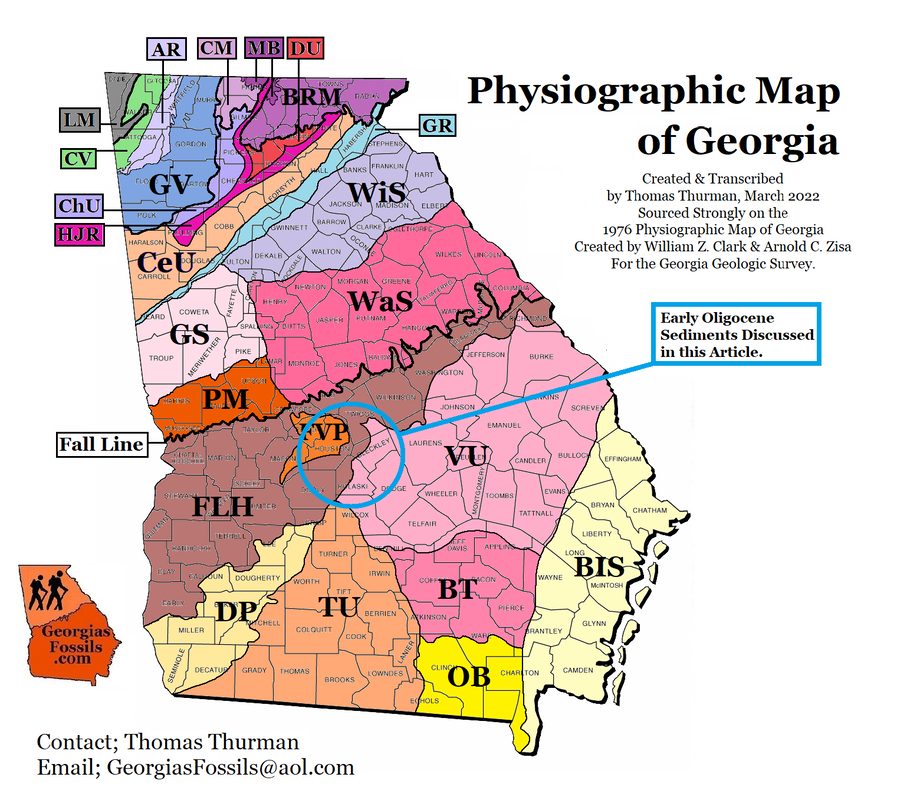

It can be difficult to express the complexity of Georgia’s Coastal Plain sediments to anyone who hasn’t spent time in the field observing them, even professionals. A geologic or physiographic map makes the Coastal Plain look so simple. A few days in the field will show that there is much we simply don't understand.

Our Early Oligocene Epoch sediments are a good lesson in complexity for the Northern Coastal Plain. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that researchers sorted out what was Late Eocene and what was Early Oligocene. Sadly, there are still professionals and university geology departments who resist the evidence and insist, without proof, that some sediments bearing Periarchus sand dollars are Early Oligocene.

Our Early Oligocene Epoch sediments are a good lesson in complexity for the Northern Coastal Plain. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that researchers sorted out what was Late Eocene and what was Early Oligocene. Sadly, there are still professionals and university geology departments who resist the evidence and insist, without proof, that some sediments bearing Periarchus sand dollars are Early Oligocene.

|

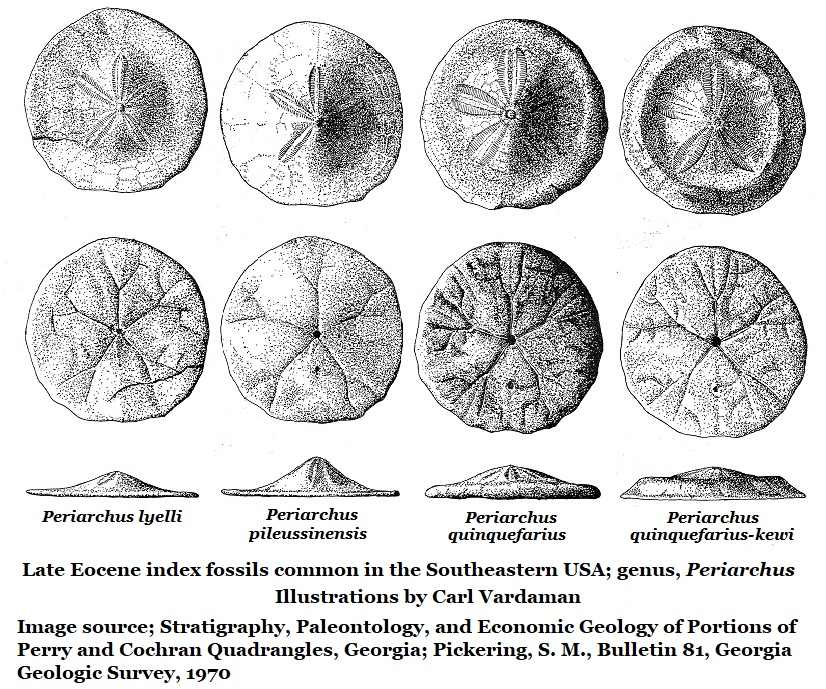

Periarchus is a genus of sand dollars, an echinoid, and an index fossil for Late Eocene sediments. An index fossil is used to establish the age of sediments. Periarchus becomes prevalent, even dominant in some southeastern sediments from 37 to 34 million years ago. But at 33.9 million years ago a global glaciation event occurred and the world cooled. Periarchus was one of the victims. At 33.9 million years ago the genus Periarchus went extinct and the Oligocene Epoch opened.

|

Illustrated below is the genre of of the various Periarchus echinoids which occur in Georgia's Late Eocene fossil beds.

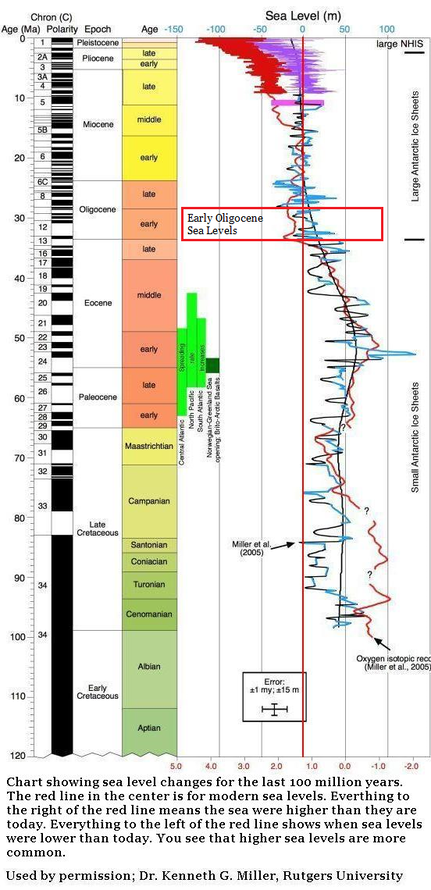

At the end of the Eocene sea levels were high, covering most of the Coastal Plain, as they had almost continuously for millions of years. The glacial event occurred and sea levels crashed, falling all the way to the Continental Shelf as water became trapped as ice. Then the world warmed again, the Early Oligocene got underway and sea levels returned, briefly, to the highs they’d known before.

But as these northern Coastal Plain sediments show, things are not as simple as they seem. We tend to assume that sediments were laid down evenly, and that fossils would occur in some reasonable order. But as these seven fossil beds show, that’s not the case.

In the relatively small geographic area of the north central Coastal Plain a great deal of variation exists in Early Oligocene sediments.

Some of this variation is due to contemporary local conditions.

Some of it is due to what happened to the sediments in the millions of years which followed; erosion, silicifications, weathering, dissolved by solution...

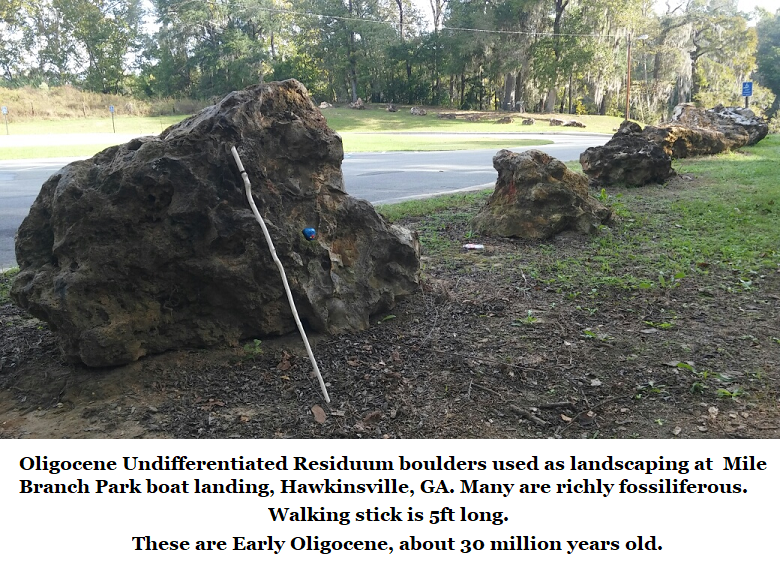

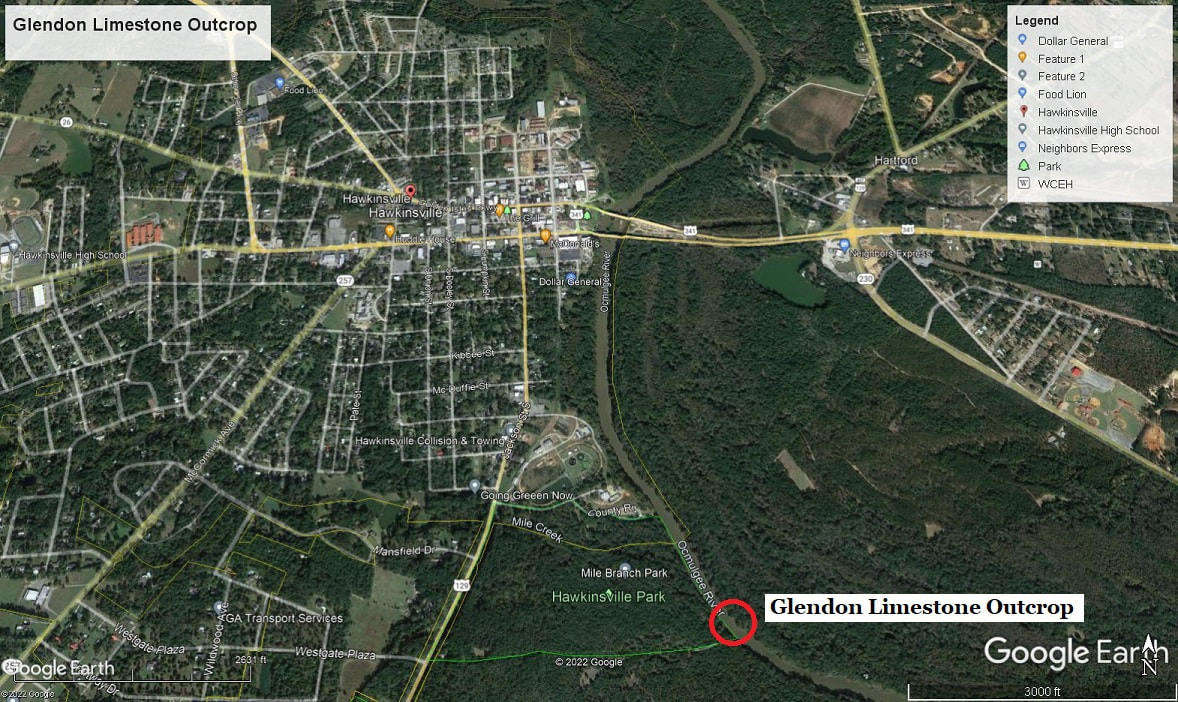

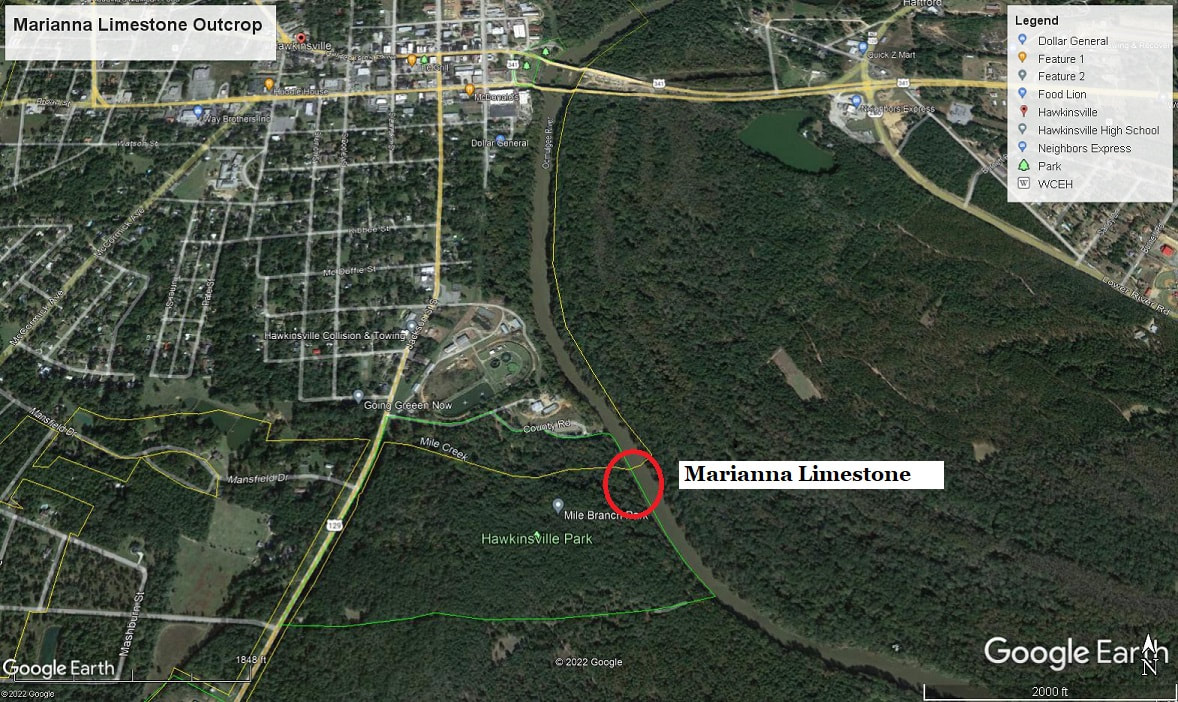

The brain teasers come in exploring and unravelling these mysteries. For instance, the Early Oligocene Residuum, which is silicified chert, the Glendon Limestone and Marianna Limestone all occur in or around Mile Branch Park just south of downtown Hawkinsville. All three are Early Oligocene and significant deposits. Yet the residuum is silicified and has experienced large scale erosion due to acidic solution. Yet the neither the Glendon nor the Marianna were ever silicified.

In the relatively small geographic area of the north central Coastal Plain a great deal of variation exists in Early Oligocene sediments.

Some of this variation is due to contemporary local conditions.

Some of it is due to what happened to the sediments in the millions of years which followed; erosion, silicifications, weathering, dissolved by solution...

The brain teasers come in exploring and unravelling these mysteries. For instance, the Early Oligocene Residuum, which is silicified chert, the Glendon Limestone and Marianna Limestone all occur in or around Mile Branch Park just south of downtown Hawkinsville. All three are Early Oligocene and significant deposits. Yet the residuum is silicified and has experienced large scale erosion due to acidic solution. Yet the neither the Glendon nor the Marianna were ever silicified.

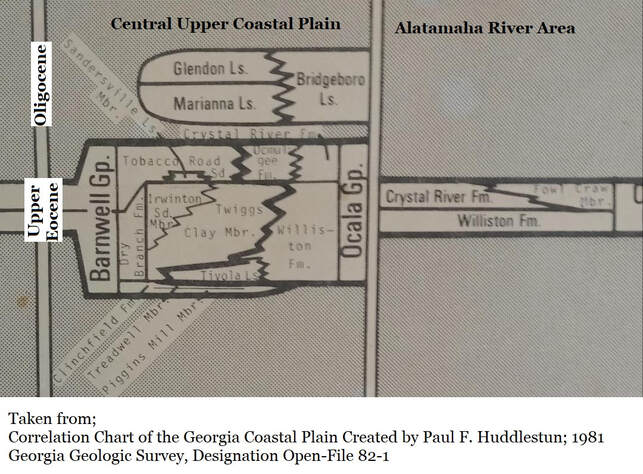

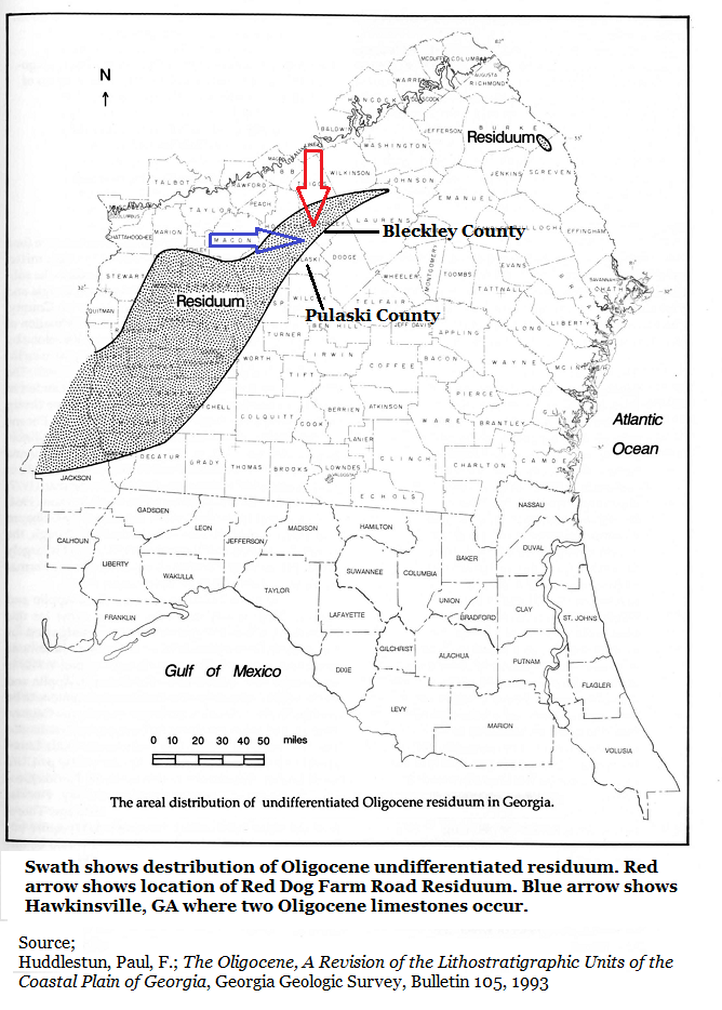

In 1981 Paul F. Huddlestun created a Coastal Plain Correlation Chart where he listed the Glendon Limestone, The Marianna Limestone, and the Bridgeboro Limestone as formations occurring on Georgia's Central Upper Coastal Plain. (See illustration below.) The Oligocene undifferentiated residuum was not included, though he knew the sediments well, simply because he did not consider it as a formation because, as residuum, it was unbedded.

However, there are beds of silicified, Early Oligocene chert which are indistinguishable from the Oligocene undifferentiated residuum; such as the (informal) Sugar Hill Railroad Bed.

However, there are beds of silicified, Early Oligocene chert which are indistinguishable from the Oligocene undifferentiated residuum; such as the (informal) Sugar Hill Railroad Bed.

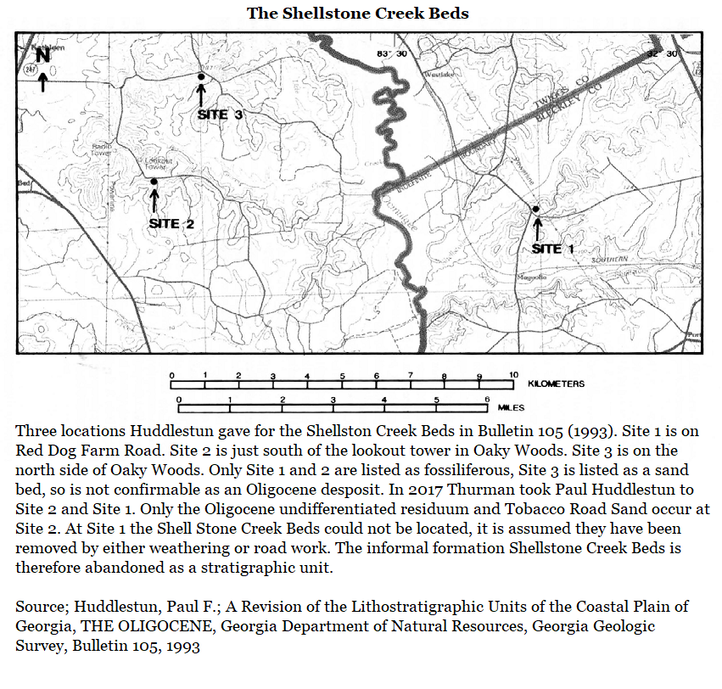

In 1993 (Bulletin 105) Huddlestun added the informal Shellstone Creek Beds on Red Dog Farm Road to the list of Early Oligocene deposits on the Central Upper Coastal Plain. As seen below he gave three locations for the Shellstone Creek Beds.

Field research in 2017, which included Paul Huddlestun could not locate the described Shellstone Creek Beds in any of the reported locations. The nomenclature is therefore abandoned.

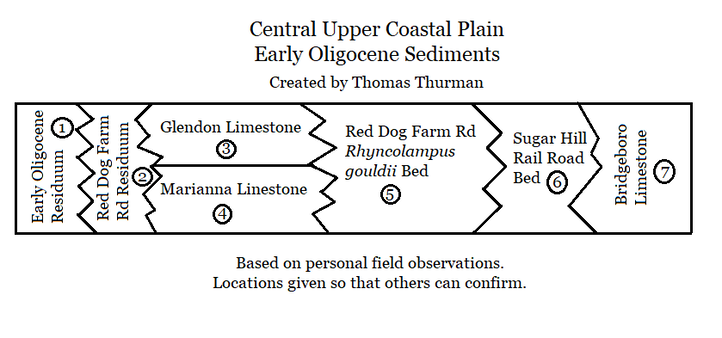

Below is a small chart recently assembled by myself (Thurman) of my personal observations of Central Upper Coastal Plain Early Oligocene Sediments.

1: Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum

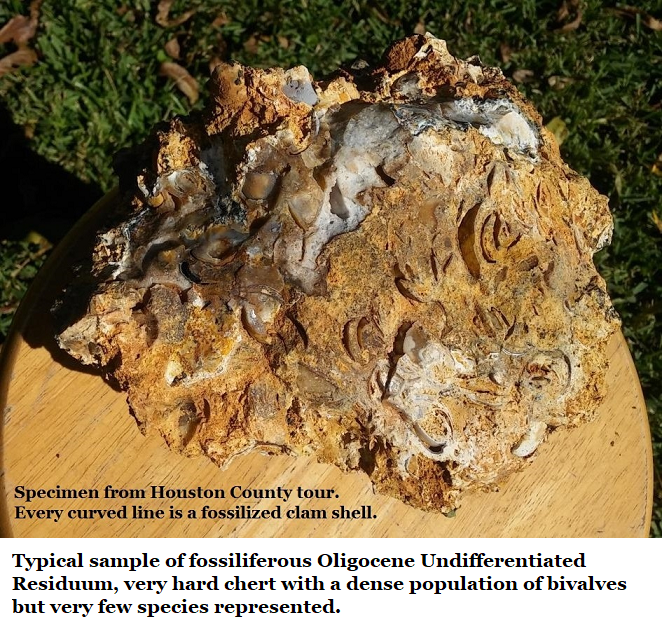

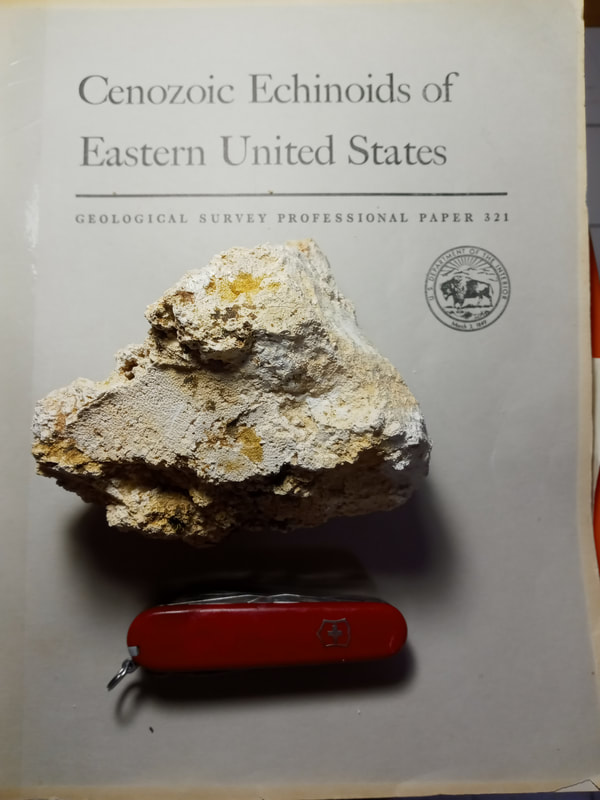

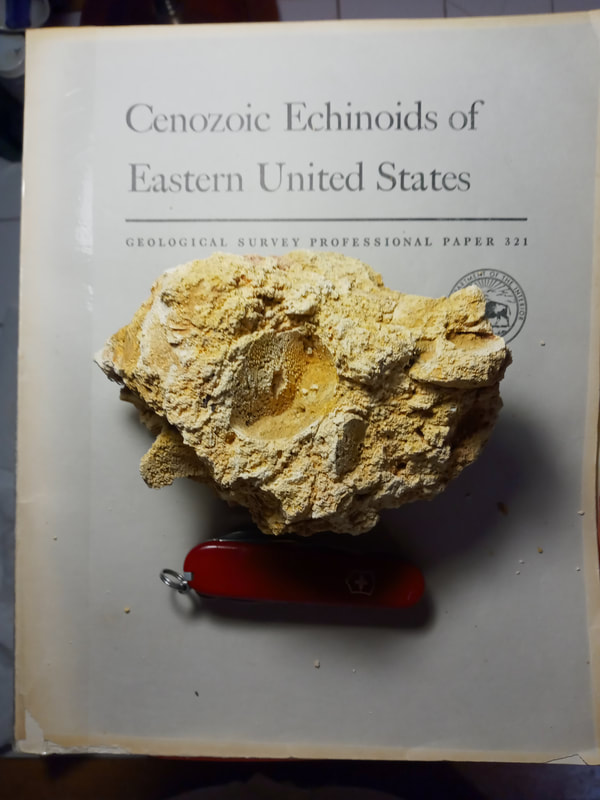

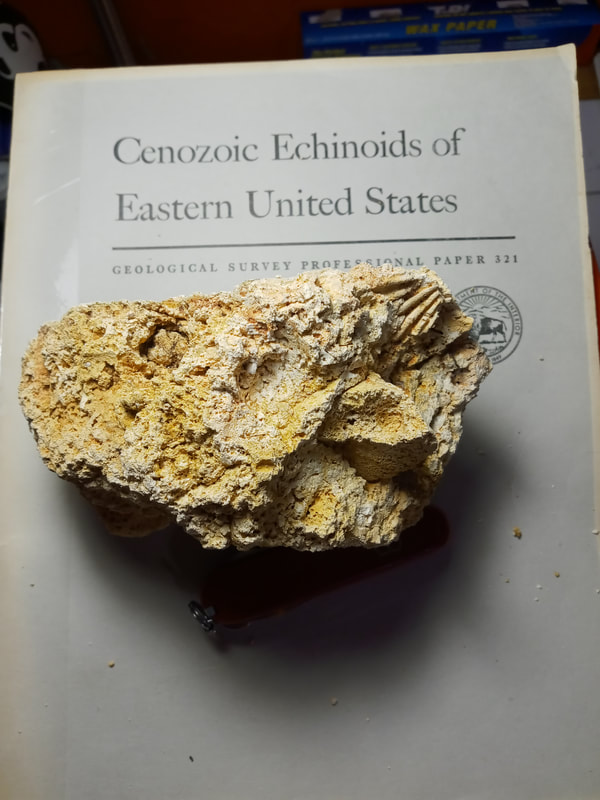

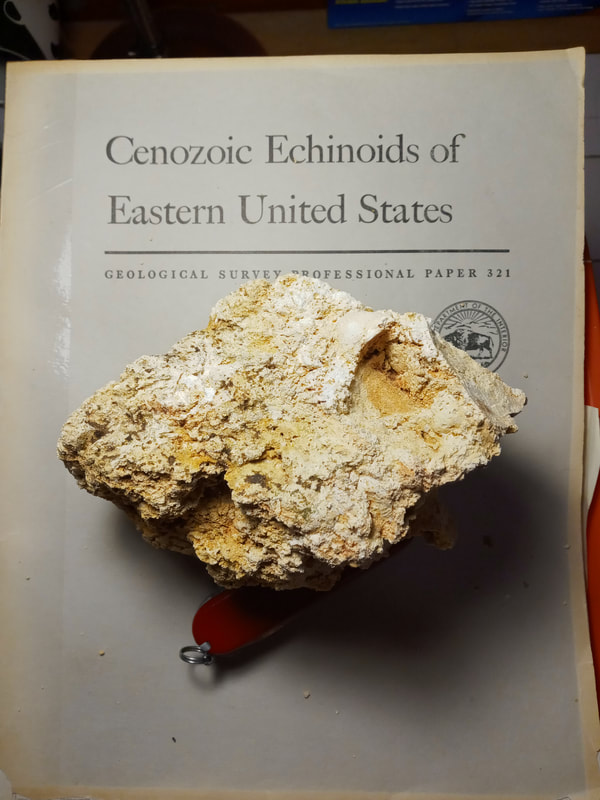

That is the official name for these sediments. They are seen today as hard boulders and stones, often full of Early Oligocene fossils, suspended in younger clays or soils. As explained in Section 15C of this website, they started as an Oligocene limestone reef. Sea levels retreated and in time the limestone was buried by later sediments.

As often happens with limestone it became an aquifer, and the groundwater it held was rich in silica. This silica infused the limestone and hardened much of it into chert. Later, perhaps during the Miocene, the water became acidic, and this dissolved away the remaining limestone. Chert isn’t affected by acid, so it was left behind.

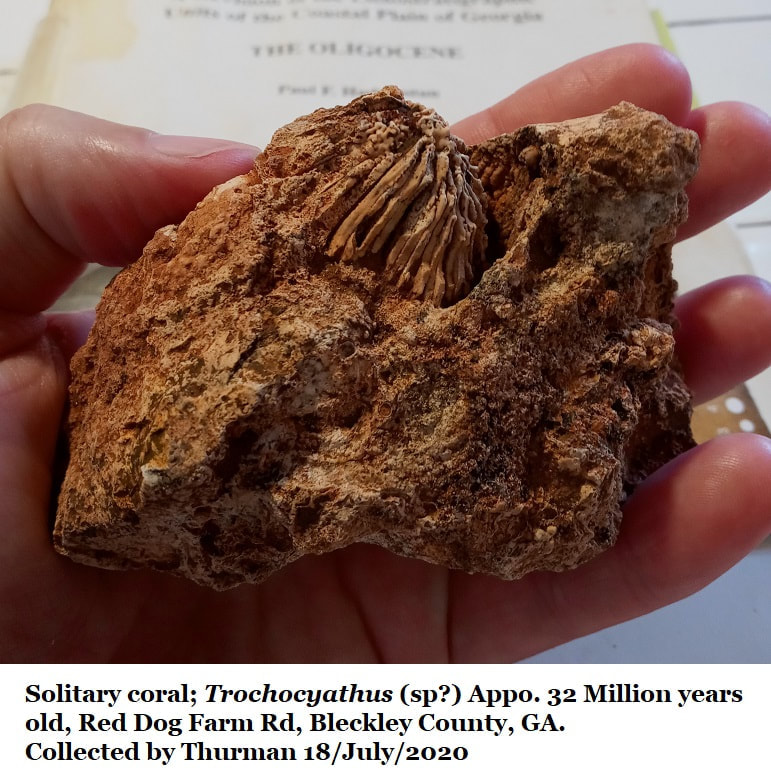

Typically, the fossils are bryozoans, bivalves, small clams, scallops and gastropods with the occasional solitary coral and rarely echinoids such as sand dollars or urchins as isolated individuals.

Undifferentiated means mixed, and there are some old reports that fossils from other periods became mixed in with the residuum (residue). But on the northern Coastal Plain I have never seen anything other than Early Oligocene fossils in this material.

That is the official name for these sediments. They are seen today as hard boulders and stones, often full of Early Oligocene fossils, suspended in younger clays or soils. As explained in Section 15C of this website, they started as an Oligocene limestone reef. Sea levels retreated and in time the limestone was buried by later sediments.

As often happens with limestone it became an aquifer, and the groundwater it held was rich in silica. This silica infused the limestone and hardened much of it into chert. Later, perhaps during the Miocene, the water became acidic, and this dissolved away the remaining limestone. Chert isn’t affected by acid, so it was left behind.

Typically, the fossils are bryozoans, bivalves, small clams, scallops and gastropods with the occasional solitary coral and rarely echinoids such as sand dollars or urchins as isolated individuals.

Undifferentiated means mixed, and there are some old reports that fossils from other periods became mixed in with the residuum (residue). But on the northern Coastal Plain I have never seen anything other than Early Oligocene fossils in this material.

2: Red Dog Farm Road Residuum (informal designation)

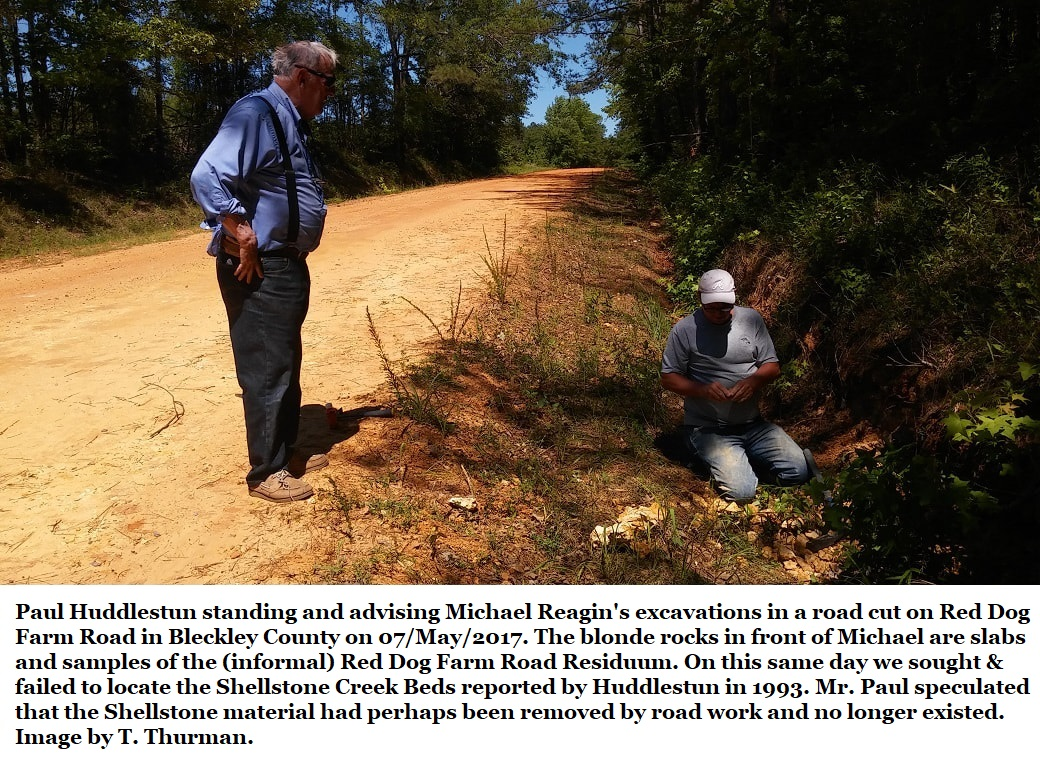

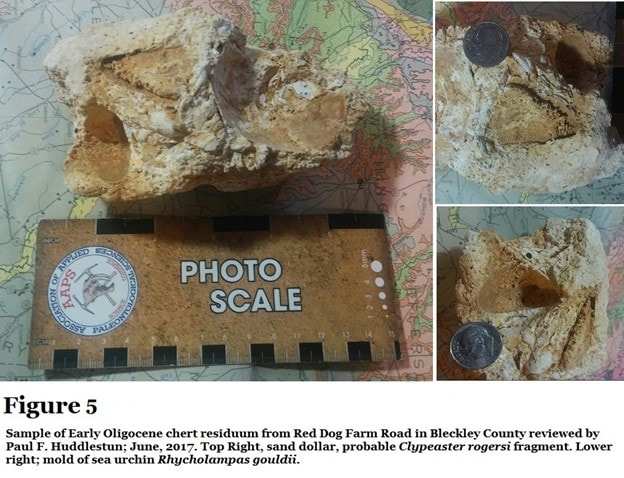

Early in 2017 Paul Huddlestun, Michael Reagin and myself excavated a site in a road cut along Red Dog Farm Rd. We recovered loose slabs of softish, blonde chert full of Early Oligocene fossils. Mr. Paul returned to his New Mexico home soon thereafter and I shipped him one of the samples to review.

His 12/June/2017 report:

"For your records, I scrubbed the chert samples you sent me with a toothbrush and water to get rid of all the extraneous material adhering to the surface. I found that most of the chert was essentially sand-free except for perhaps a stray fine-grained sand. The chert matrix had the appearance of having been formed from fine bioclastic debris in apparent random orientation except that all the “bioclastic” particles could not be identified as to origin because of silicification and loss of original surface details. I did see what appears to be the silicified remains of a Clypeaster rogersi. It is certainly a sand dollar and it has the correct outline for a Clypeaster rogersi and not a Periarchus quinquefarius. There are also what appears to be veins of coarse grained, poorly sorted sand in the chunks of chert. These quartz sand concentrations appear to be 2-dimensional and not small lenses or pods enveloped within the chert. I would expect the later distribution if the poorly sorted sand was originally incorporated into the limestone/chert in a disturbance event. I often see in impure limestones and dolostones. It appears the coarse sand migrated downward along veins into the limestone/chert during the subaerial weathering process that resulted in the silicification of the original limestone. It also suggests that the Miocene Altamaha Formation originally overlay the Oligocene limestone in the Red Dog Road area. It is curious that the matrix of the chert, given that it was once formed from bioclastic debris, appears to be unlike the lithology of the Marianna and Glendon Limestones on the Ocmulgee River at Hawkinsville."

This is a very informal name, like the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum in section 1 off this page, this material was once part of a limestone reef which became inundated with silica and became chert. The remaining limestone was dissolved away at a later period, maybe during the Miocene.

Unlike the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum, echinoids such as sea urchins and sand dollars are abundant, but clams, scallops and gastropods seem rare.

I am aware of this material occurring nowhere else.

Early in 2017 Paul Huddlestun, Michael Reagin and myself excavated a site in a road cut along Red Dog Farm Rd. We recovered loose slabs of softish, blonde chert full of Early Oligocene fossils. Mr. Paul returned to his New Mexico home soon thereafter and I shipped him one of the samples to review.

His 12/June/2017 report:

"For your records, I scrubbed the chert samples you sent me with a toothbrush and water to get rid of all the extraneous material adhering to the surface. I found that most of the chert was essentially sand-free except for perhaps a stray fine-grained sand. The chert matrix had the appearance of having been formed from fine bioclastic debris in apparent random orientation except that all the “bioclastic” particles could not be identified as to origin because of silicification and loss of original surface details. I did see what appears to be the silicified remains of a Clypeaster rogersi. It is certainly a sand dollar and it has the correct outline for a Clypeaster rogersi and not a Periarchus quinquefarius. There are also what appears to be veins of coarse grained, poorly sorted sand in the chunks of chert. These quartz sand concentrations appear to be 2-dimensional and not small lenses or pods enveloped within the chert. I would expect the later distribution if the poorly sorted sand was originally incorporated into the limestone/chert in a disturbance event. I often see in impure limestones and dolostones. It appears the coarse sand migrated downward along veins into the limestone/chert during the subaerial weathering process that resulted in the silicification of the original limestone. It also suggests that the Miocene Altamaha Formation originally overlay the Oligocene limestone in the Red Dog Road area. It is curious that the matrix of the chert, given that it was once formed from bioclastic debris, appears to be unlike the lithology of the Marianna and Glendon Limestones on the Ocmulgee River at Hawkinsville."

This is a very informal name, like the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum in section 1 off this page, this material was once part of a limestone reef which became inundated with silica and became chert. The remaining limestone was dissolved away at a later period, maybe during the Miocene.

Unlike the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum, echinoids such as sea urchins and sand dollars are abundant, but clams, scallops and gastropods seem rare.

I am aware of this material occurring nowhere else.

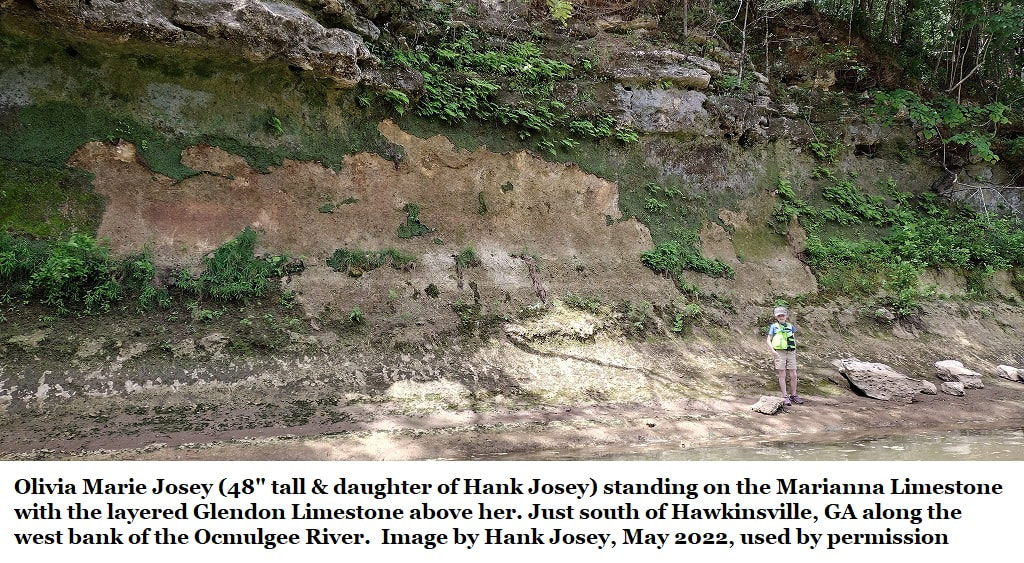

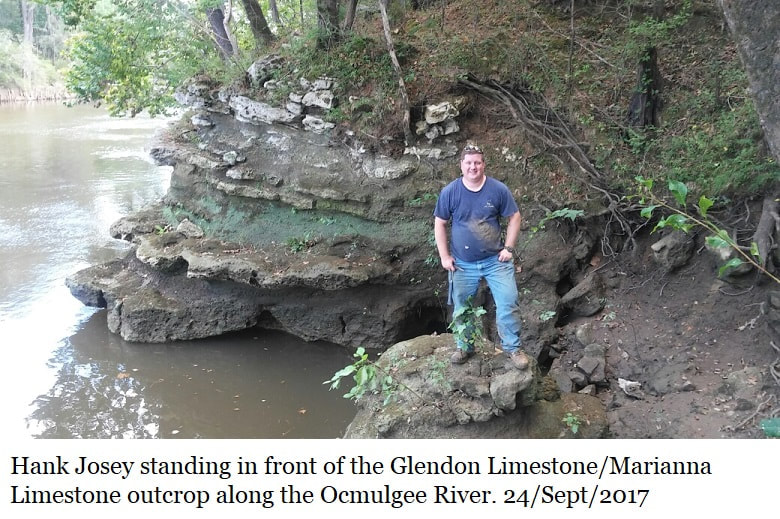

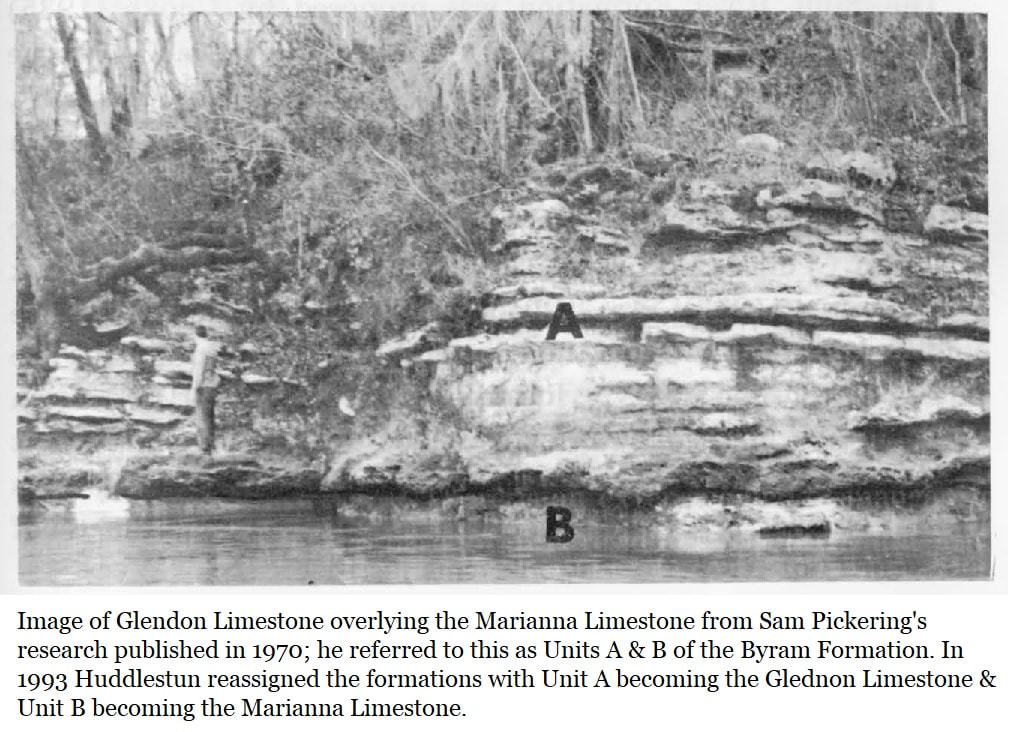

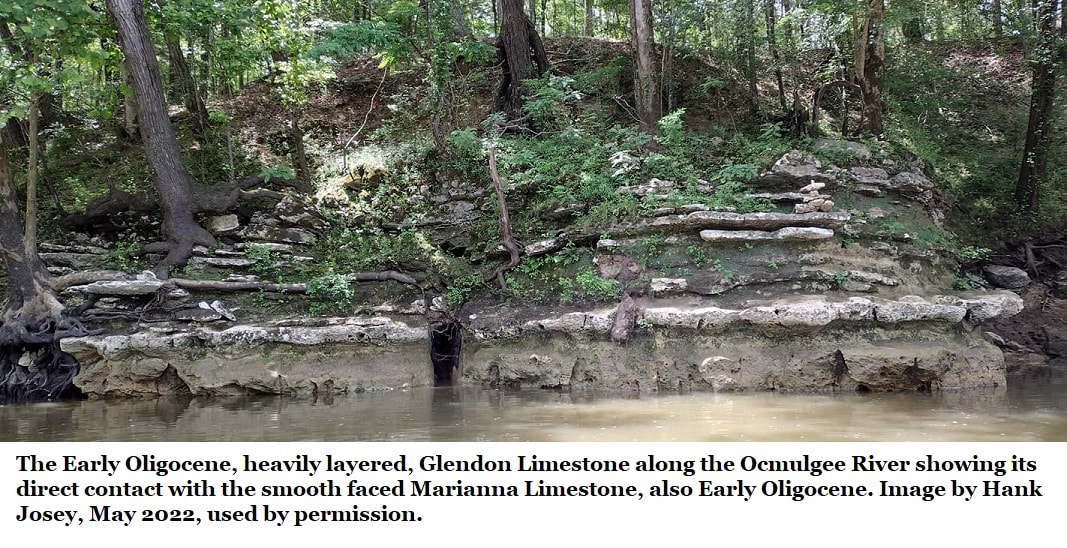

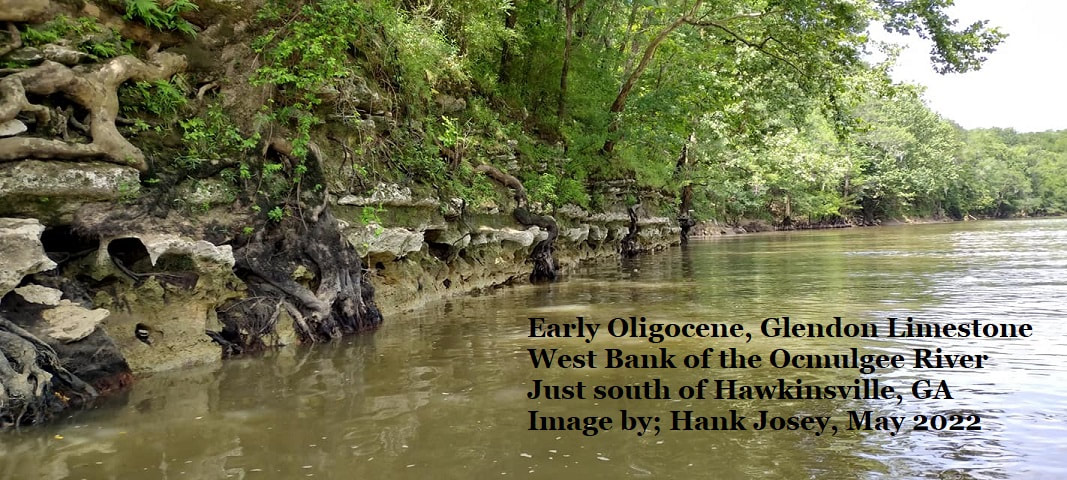

3: Glendon Limestone

Just about a mile down river from Mile Branch Park Boat Landing on the southside of Hawkinsville you’ll find Georgia’s only exposure of the Early Oligocene Glendon Limestone. Bear in mind that this is still a limestone and was never inundated with silica and changed to chert. Neither has it ever been dissolved by acidic ground water.

Just about a mile down river from Mile Branch Park Boat Landing on the southside of Hawkinsville you’ll find Georgia’s only exposure of the Early Oligocene Glendon Limestone. Bear in mind that this is still a limestone and was never inundated with silica and changed to chert. Neither has it ever been dissolved by acidic ground water.

The Glendon Limestone was named, and the type locality set by C. W. Cooke in 1918 for Early Oligocene sediments in a Clarke County, Alabama quarry which Paul Huddlestun reported 1993 as abandon and overgrown.

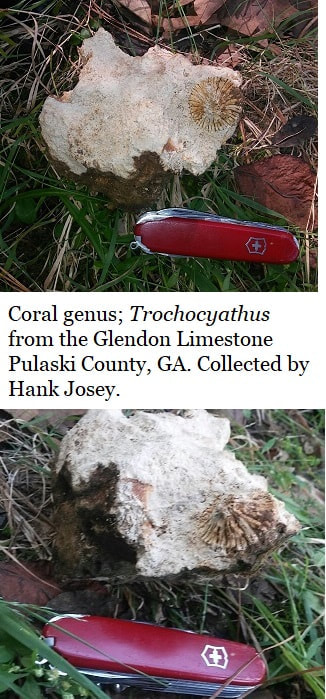

The Glendon Limestone is described in detail in section 15b of this website. While rich in microfossils the Glendon limestone does not contain many fossils observable in the field.

Paul Huddlestun described the Glendon in 1993:

“The Glendon Limestone on the Ocmulgee River consists of alternating hard and soft layers (ledges and reentrants) of limestone. The limestone in the ledges are partially recrystallized and consists of approximately 94 percent calcium carbonate (Pickering, 1970, p. 51). The limestone in the reentrants is argillaceous, silty, consists of approximately 70 percent calcium carbonate, and contains conspicuous carbonaceous material. The Glendon Limestone on the Ocmulgee River differs from typical Glendon Limestone in being very sparsely macro-fossiliferous, and it does not contain a significant number of Lepidocyclina as is characteristic of the formation in Alabama. The soft limestone, however, is abundantly micro-fossiliferous.”

In 1970 Sam Pickering called the Glendon Limestone Unit A of the Byram Formation and described it thusly (For clarity I have substituted “Unit A” for “Glendon”);

“The rhythmic alternating nature of the (Glendon) lithology of suggests that environmental conditions fluctuated regularly during deposition, probably due to varying availabilities of clastic silt and clay. The base of each of the tan clay beds of (the Glendon) contains a very great abundance of fossil material indicating that probably the influx of silt and clay killed large numbers of organisms by clogging their breathing apparatus. Most of the fossil remains observed in (the Glendon) were in their approximate living positions, indicating a probable life assemblage rather than a sedimentary accumulation of miscellaneous fossil material. Corals were observed to be considerably more abundant in the lower bed of limestone than in any other part of the unit. This limestone bed is also the thickest bed probably indicating that deposition occurred over a longer period of time during which corals could become more firmly established.”

Paul Huddlestun described the Glendon in 1993:

“The Glendon Limestone on the Ocmulgee River consists of alternating hard and soft layers (ledges and reentrants) of limestone. The limestone in the ledges are partially recrystallized and consists of approximately 94 percent calcium carbonate (Pickering, 1970, p. 51). The limestone in the reentrants is argillaceous, silty, consists of approximately 70 percent calcium carbonate, and contains conspicuous carbonaceous material. The Glendon Limestone on the Ocmulgee River differs from typical Glendon Limestone in being very sparsely macro-fossiliferous, and it does not contain a significant number of Lepidocyclina as is characteristic of the formation in Alabama. The soft limestone, however, is abundantly micro-fossiliferous.”

In 1970 Sam Pickering called the Glendon Limestone Unit A of the Byram Formation and described it thusly (For clarity I have substituted “Unit A” for “Glendon”);

“The rhythmic alternating nature of the (Glendon) lithology of suggests that environmental conditions fluctuated regularly during deposition, probably due to varying availabilities of clastic silt and clay. The base of each of the tan clay beds of (the Glendon) contains a very great abundance of fossil material indicating that probably the influx of silt and clay killed large numbers of organisms by clogging their breathing apparatus. Most of the fossil remains observed in (the Glendon) were in their approximate living positions, indicating a probable life assemblage rather than a sedimentary accumulation of miscellaneous fossil material. Corals were observed to be considerably more abundant in the lower bed of limestone than in any other part of the unit. This limestone bed is also the thickest bed probably indicating that deposition occurred over a longer period of time during which corals could become more firmly established.”

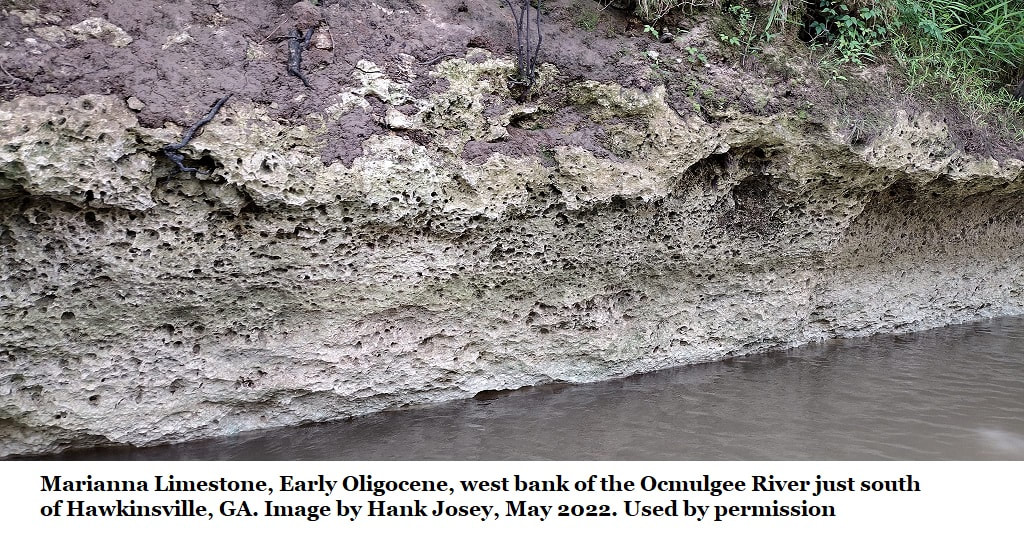

4: The Marianna Limestone

Also along the Ocmulgee River is the Marianna Limestone, but unless you have a boat the only outcrop observable is along the bed of last 100 yards of Mile Creek, where it flows over the Marianna Limestone before emptying into the Ocmulgee River. The Glendon Limestone is conspicoulsy absent at this location. The Marianna is also Early Oligocene. It is also limestone, neither dissolved away by acids nor silicified and turned to chert.

It is described in detail in Section 15A of this website and was named for matching sediments in Marianna, Jackson County, in western Florida.

Only in Georgia does the Florida Marianna Limestone and Alabama Glendon Limestone occur together.

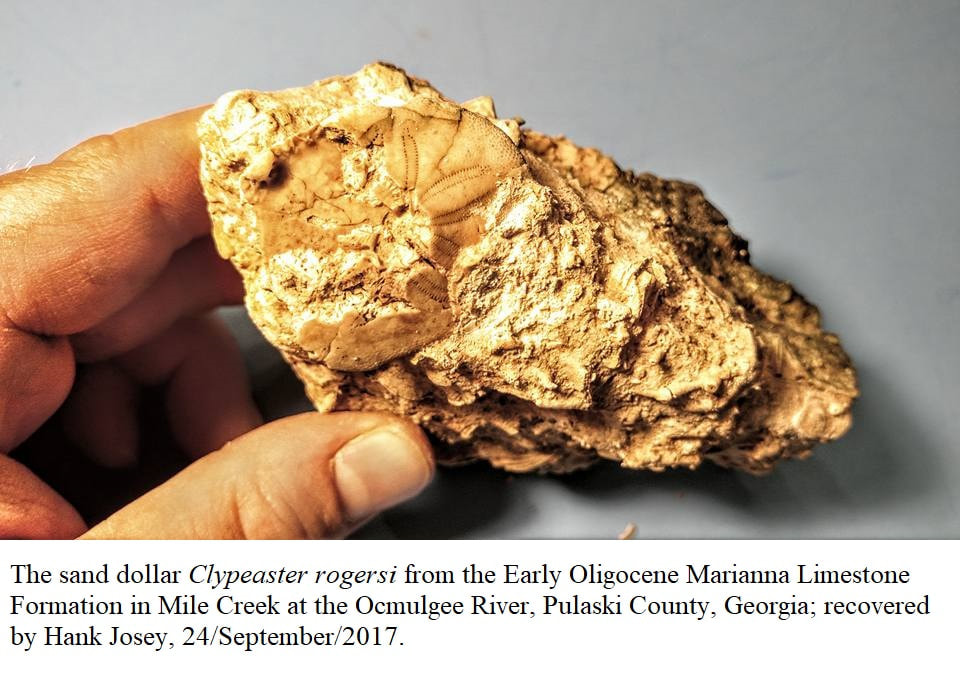

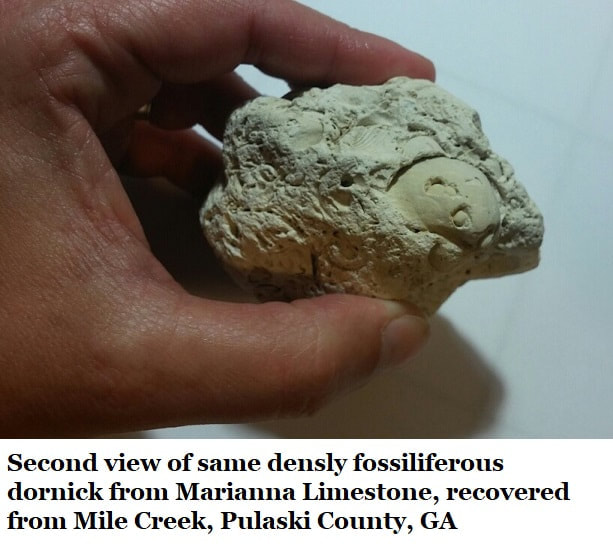

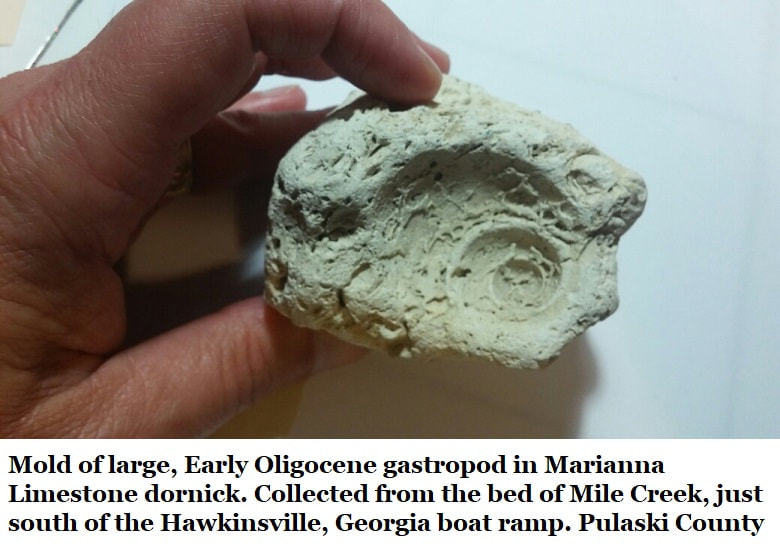

The Marianna is much richer in fossils than the Glendon, holding a wealth of invertebrate material. Collected samples from the creek bed show abundant Lepidocyclina mantelli forams often stacked like pancakes, bryozoans, random echinoid spines & fragmentary shells. Hank Josey recovered a complete, if somewhat crushed, Clypeaster rogersi, (image) from this location on 24/Sept/2017.

Some years ago I (Thurman) recovered the madreporite of a sea star. A madreporite is the “stone” on the top of a sea star; it’s a calcareous (made of calcium) filter where water is drawn into the vascular system. Sadly, madreporites aren’t useful for identifying species but the only part of a sea star which frequently fossilizes.

The Marianna Limestone reference locality in Georgia rest beneath the Glendon limestone for a thickness of a few feet depending on river level. It only occurs in one core sample from Pulaski County (GGS-3111) and is 21 feet thick, occurring between 75 & 96 feet subsurface. The Glendon is absent at the core sample as it is at Mile Creek. No precise location is given for the core sample but it seems to be very near Hawkinsville.

In 1970 Pickering described the Marianna Limestone as “white to pale cream”, 98.41% pure calcium carbonate, plastic, soft chalk with isolated fossils. Pickering described the sediments as possessing abundant small foraminifera. He noted the “coin-shaped large foraminifera Lepidocyclina mantelli, occurs most abundantly in a bed three feet thick in which it is scattered helter-skelter at all orientations but the fragile test is generally unbroken.”

Also along the Ocmulgee River is the Marianna Limestone, but unless you have a boat the only outcrop observable is along the bed of last 100 yards of Mile Creek, where it flows over the Marianna Limestone before emptying into the Ocmulgee River. The Glendon Limestone is conspicoulsy absent at this location. The Marianna is also Early Oligocene. It is also limestone, neither dissolved away by acids nor silicified and turned to chert.

It is described in detail in Section 15A of this website and was named for matching sediments in Marianna, Jackson County, in western Florida.

Only in Georgia does the Florida Marianna Limestone and Alabama Glendon Limestone occur together.

The Marianna is much richer in fossils than the Glendon, holding a wealth of invertebrate material. Collected samples from the creek bed show abundant Lepidocyclina mantelli forams often stacked like pancakes, bryozoans, random echinoid spines & fragmentary shells. Hank Josey recovered a complete, if somewhat crushed, Clypeaster rogersi, (image) from this location on 24/Sept/2017.

Some years ago I (Thurman) recovered the madreporite of a sea star. A madreporite is the “stone” on the top of a sea star; it’s a calcareous (made of calcium) filter where water is drawn into the vascular system. Sadly, madreporites aren’t useful for identifying species but the only part of a sea star which frequently fossilizes.

The Marianna Limestone reference locality in Georgia rest beneath the Glendon limestone for a thickness of a few feet depending on river level. It only occurs in one core sample from Pulaski County (GGS-3111) and is 21 feet thick, occurring between 75 & 96 feet subsurface. The Glendon is absent at the core sample as it is at Mile Creek. No precise location is given for the core sample but it seems to be very near Hawkinsville.

In 1970 Pickering described the Marianna Limestone as “white to pale cream”, 98.41% pure calcium carbonate, plastic, soft chalk with isolated fossils. Pickering described the sediments as possessing abundant small foraminifera. He noted the “coin-shaped large foraminifera Lepidocyclina mantelli, occurs most abundantly in a bed three feet thick in which it is scattered helter-skelter at all orientations but the fragile test is generally unbroken.”

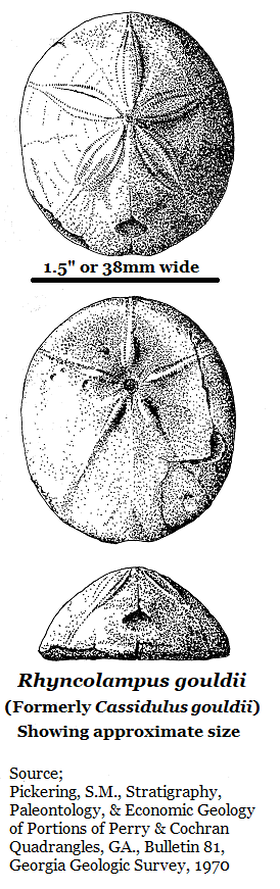

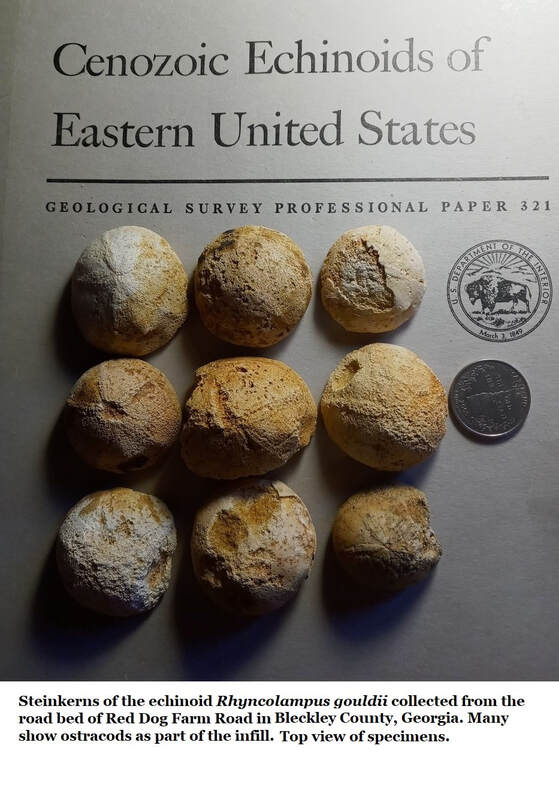

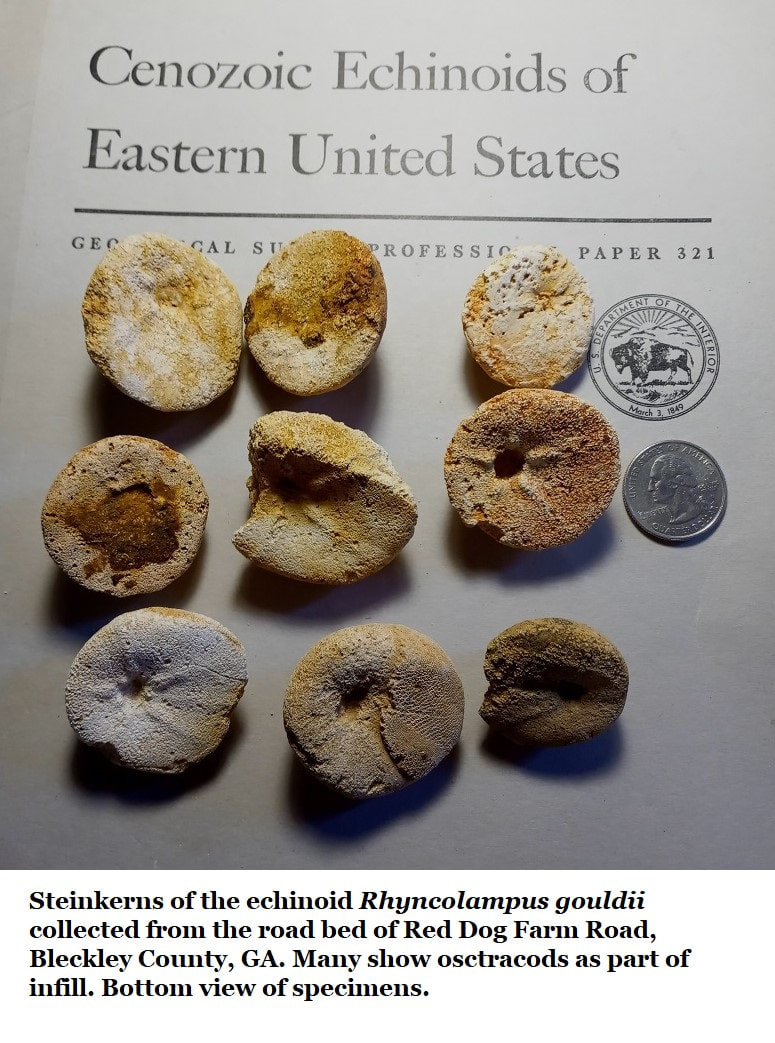

5: Red Dog Farm Road Rhyncolampus gouldii bed

(Informal Designation)

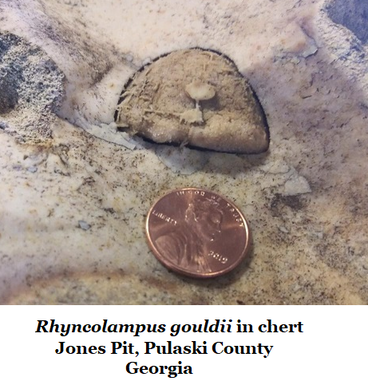

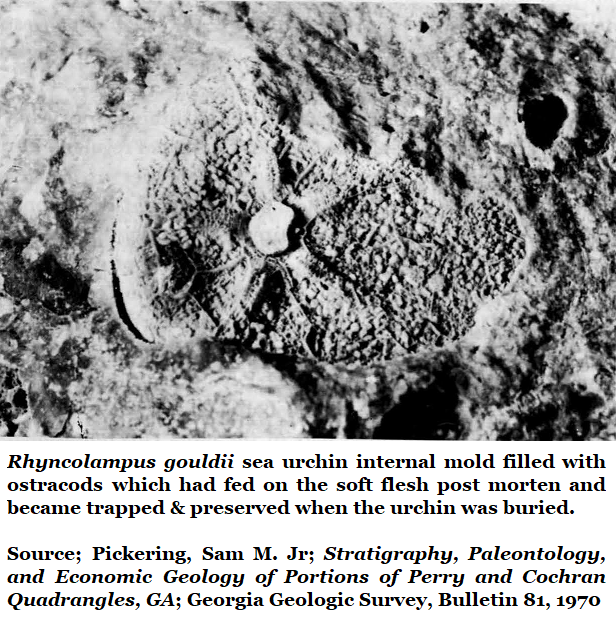

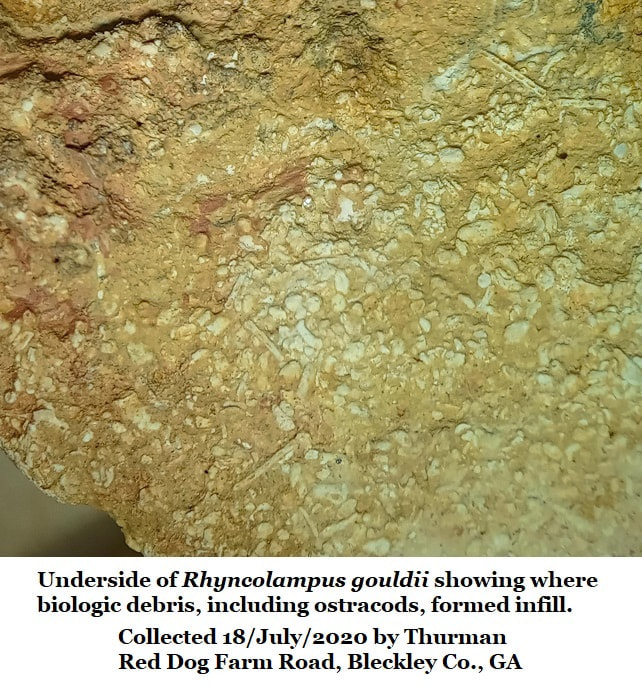

Steinkerns of Rhyncolampus gouldii occur in the roadbed of Bleckley County’s Red Dog Farm Road. I have picked up as many as 10 in just a few minutes right after a rain. See Section 15E of this website for further details.

It's entirely possible that these are from the same sediments as the Read Dog Farm Road Residuum discussed in #2 of this page. While they are both the same age, the road bed sea biscuits tend to be complete or mostly complete and darker stained with iron oxide than the slabs found in the roadcut wall. Some Clypeaster rogersi sand dollars occur in the roadbed with the sea biscuits, but they are very fragmentary and usually only as imprints, it takes a sharp eye to find one. The sand dollars seem to be very rare in the road bed, but far more common in the blonde slabs of the road cut which perhaps occur just a little higher in elevation.

The Steinkerns are also full of ostracods, typically, where ostracods seemed rare in the slabs.

(Informal Designation)

Steinkerns of Rhyncolampus gouldii occur in the roadbed of Bleckley County’s Red Dog Farm Road. I have picked up as many as 10 in just a few minutes right after a rain. See Section 15E of this website for further details.

It's entirely possible that these are from the same sediments as the Read Dog Farm Road Residuum discussed in #2 of this page. While they are both the same age, the road bed sea biscuits tend to be complete or mostly complete and darker stained with iron oxide than the slabs found in the roadcut wall. Some Clypeaster rogersi sand dollars occur in the roadbed with the sea biscuits, but they are very fragmentary and usually only as imprints, it takes a sharp eye to find one. The sand dollars seem to be very rare in the road bed, but far more common in the blonde slabs of the road cut which perhaps occur just a little higher in elevation.

The Steinkerns are also full of ostracods, typically, where ostracods seemed rare in the slabs.

6: Sugar Hill Railroad Bed

Years ago I interviewed Sam Pickering and asked him a good fossil collecting site in Houston County. Pickering did a tour as State Geologist and in 1970 he published a paper covering the paleontology of that very area. He instantly answered, “Sugar Hill”, I later learned that this was an Early Oligocene site. In his day Sugar Hill was accessible. Sadly, its now fenced private property. But there’s a lot of paleontology going on in south Houston County.

Years ago I interviewed Sam Pickering and asked him a good fossil collecting site in Houston County. Pickering did a tour as State Geologist and in 1970 he published a paper covering the paleontology of that very area. He instantly answered, “Sugar Hill”, I later learned that this was an Early Oligocene site. In his day Sugar Hill was accessible. Sadly, its now fenced private property. But there’s a lot of paleontology going on in south Houston County.

In that same 1970 report Pickering referred to the Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum as the Flint River Formation and discussed it in detail including creating a partial list of its fossils and several excellent illustrations. He recognized that most of the fossil bearing sediments were residual in nature… They were chert, formed from limestone. The host limestone was long gone, dissolved away by acidic groundwater. Chert is not affected by acid. So, a residue of chert stones were left behind ranging from dornicks (hand samples) to boulders.

To quote Pickering (1970)

“The Flint River Formation in outcrop is composed of boulders and dornicks of chert; nodules, geodes, and large concretionary masses of limonite, hematite, and goethite; iron and chert-cemented sandstone and conglomerate; stiff to plastic varicolored clay; and manganiferous (magnesium-rich) sand. No carbonate material was observed… The silica in the Flint River Formation occurs as triploi, chalcedony, porcelaneous chert, and silicified breccia (sandstone). A residual origin of the chert due to silicification of weathering limestone is indicated…”

To quote Pickering (1970)

“The Flint River Formation in outcrop is composed of boulders and dornicks of chert; nodules, geodes, and large concretionary masses of limonite, hematite, and goethite; iron and chert-cemented sandstone and conglomerate; stiff to plastic varicolored clay; and manganiferous (magnesium-rich) sand. No carbonate material was observed… The silica in the Flint River Formation occurs as triploi, chalcedony, porcelaneous chert, and silicified breccia (sandstone). A residual origin of the chert due to silicification of weathering limestone is indicated…”

In 1993 Huddlestun overturned the Flint River Formation and reassigned the material as Undifferentiated Residuum on the grounds that there were no bedded exposures and there was a mixture of fossils from other periods. (There are very rare Eocene fossils which were likely silicified with overlying Oligocene material before both weathered out with erosion.)

The more I look at the Oligocene residuum, the more I agree with Pickering. There is such a profusion of Early Oligocene material in the area that naming this something besides residuum helps clarify things. However, for our purposes here we’ll stay with Huddlestun’s Undifferentiated Residuum.

The more I look at the Oligocene residuum, the more I agree with Pickering. There is such a profusion of Early Oligocene material in the area that naming this something besides residuum helps clarify things. However, for our purposes here we’ll stay with Huddlestun’s Undifferentiated Residuum.

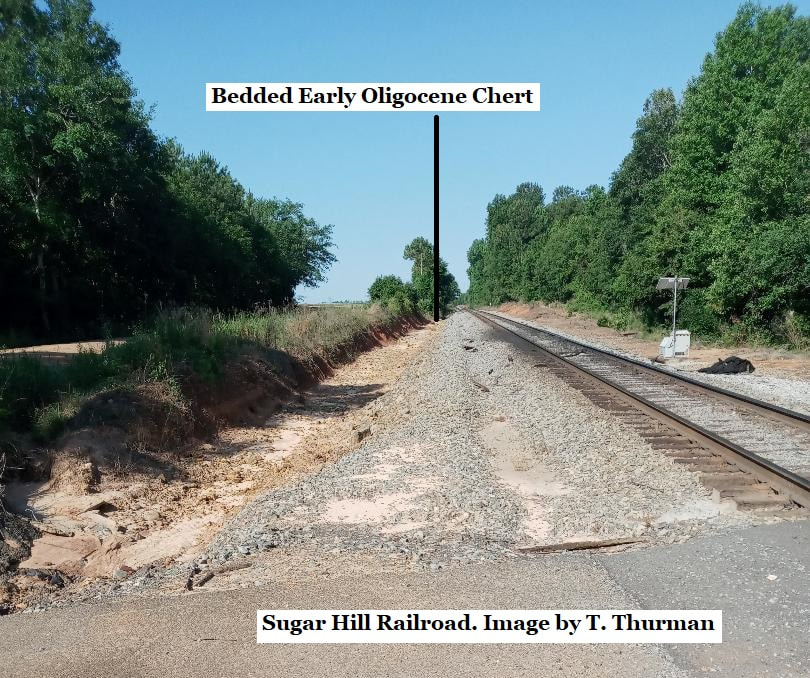

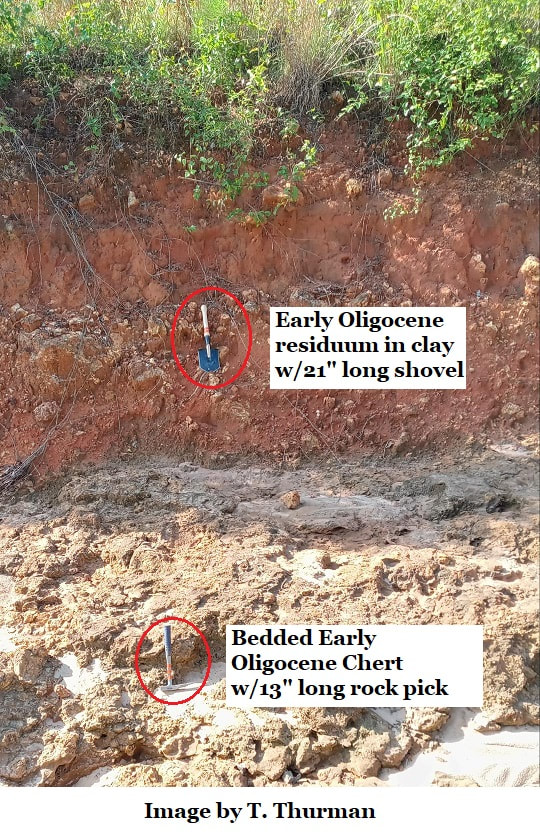

In southernmost foot of Houston County, about 100 yards SW of where the railroad track intersects the junction of Sugar Hill Road and County Line Road you’ll find a railroad cut about seven feet deep. Occurring at the base of this is bedded Early Oligocene chert.

In the stiff red clay wall above the bedded chert is the typical suspended dornicks of Early Oligocene residuum, some few bearing fossils. Also observed were a scattering of small fossil rich boulders typical of the local Early Oligocene residuum, these were lying loose on the ground and I assume they had weathered out of the embankment. However, no fossils were observed in the bedded chert. That’s not surprising since much of the Oligocene residuum is free of fossils. The lack of fossils also suggest different local conditions when this material was laid down.

The fact that dornicks occur suspended in clay above the bed of chert is interesting, this suggests that there was once, perhaps, multiple beds of Early Oligocene limestone present.

Again, such a diversity of different conditions show that the Early Oligocene was more variable than previously suspected.

In the stiff red clay wall above the bedded chert is the typical suspended dornicks of Early Oligocene residuum, some few bearing fossils. Also observed were a scattering of small fossil rich boulders typical of the local Early Oligocene residuum, these were lying loose on the ground and I assume they had weathered out of the embankment. However, no fossils were observed in the bedded chert. That’s not surprising since much of the Oligocene residuum is free of fossils. The lack of fossils also suggest different local conditions when this material was laid down.

The fact that dornicks occur suspended in clay above the bed of chert is interesting, this suggests that there was once, perhaps, multiple beds of Early Oligocene limestone present.

Again, such a diversity of different conditions show that the Early Oligocene was more variable than previously suspected.

7: Bridgeboro Limestone

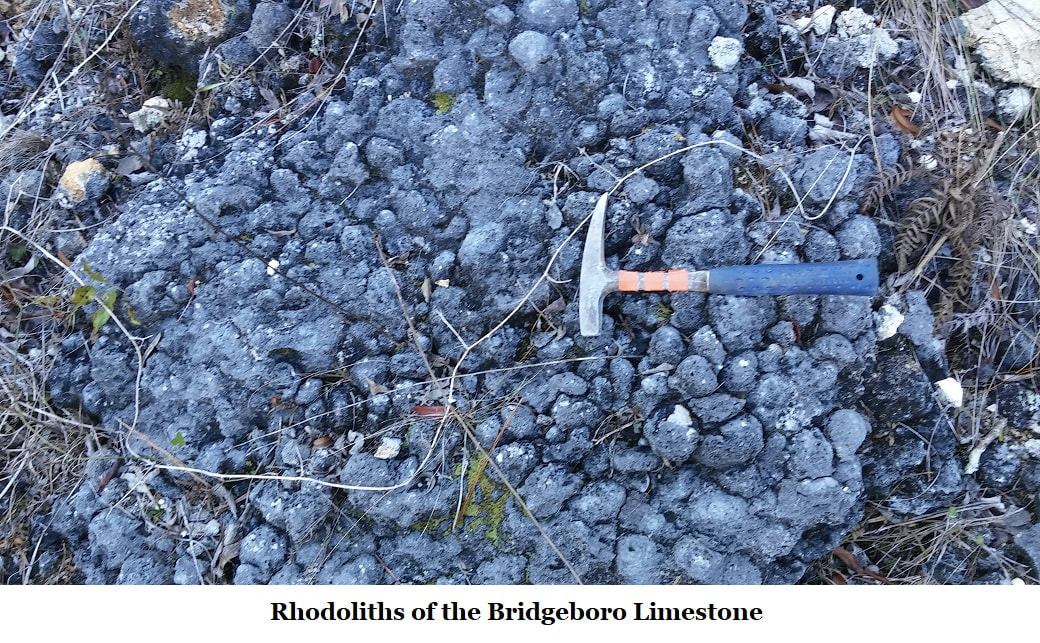

There are large exposures of the Early Oligocene Bridgeboro Limestone in southwest Georgia, for more information on the scientifically important formation see Section 8 of this website.

The limestone is primarily composed of algae rhodoliths which tended to grow in rounded shapes when exposed to the strong Suwannee Current, but flattened shapes in quieter waters.

There are large exposures of the Early Oligocene Bridgeboro Limestone in southwest Georgia, for more information on the scientifically important formation see Section 8 of this website.

The limestone is primarily composed of algae rhodoliths which tended to grow in rounded shapes when exposed to the strong Suwannee Current, but flattened shapes in quieter waters.

In 1993 Huddlestun reported “…The northern band of Bridgeboro Limestone (on the northern flank of the Gulf Trough) extends from the vicinity of Dublin in Laurens County, in the northeast, southwestward to at least Decatur County, a distance of approximately 100 miles (160 km).”

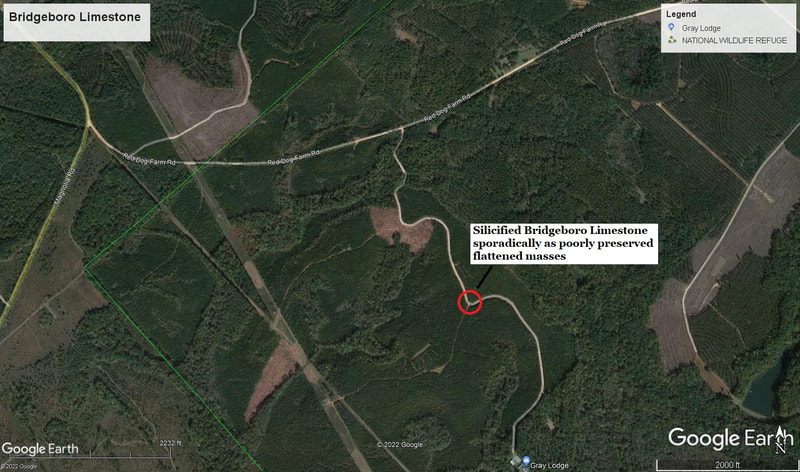

Along Red Dog Farm Road there is one fairly well-maintained side road branching off to the south. Sadly this road has recently become private and grown a locked gate. In the recent past you could drive its length.

About a half mile down there is a sharp, 90° turn to the east which skirts a small promontory which appears to me as a silicified, weathered exposure of the Bridgeboro Limestone. In this case with flattened, low energy environment rhodoliths. This is west, south-west of Dublin.

Along Red Dog Farm Road there is one fairly well-maintained side road branching off to the south. Sadly this road has recently become private and grown a locked gate. In the recent past you could drive its length.

About a half mile down there is a sharp, 90° turn to the east which skirts a small promontory which appears to me as a silicified, weathered exposure of the Bridgeboro Limestone. In this case with flattened, low energy environment rhodoliths. This is west, south-west of Dublin.

References:

Paul F. Huddlestun; A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, THE OLIGOCENE, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 105, 1993

Sam M. Pickering Jr., Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; Bulletin 81, The Geological Survey of Georgia, Dept of Mines, Mining & Geology 1970.

Paul F. Huddlestun; Correlation Chart of the Georgia Coastal Plain, 1981, Georgia Geologic Survey Designation, Open-File 82-1

Paul F. Huddlestun; A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, THE OLIGOCENE, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 105, 1993

Sam M. Pickering Jr., Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; Bulletin 81, The Geological Survey of Georgia, Dept of Mines, Mining & Geology 1970.

Paul F. Huddlestun; Correlation Chart of the Georgia Coastal Plain, 1981, Georgia Geologic Survey Designation, Open-File 82-1