25H: Collections & Stewardship

Of Georgia’s Fossils

By Thomas Thurman

Posted 23/January/2022

Sam Pickering & Fernbank

About two decades ago, on a Saturday afternoon, I interviewed Sam Pickering in his home office in Macon, Georgia. Sam stood as the Georgia State Geologist from 1972 through 1978 and had initiated an unprecedented wave of field research which continued well into the 1990s. Sam went on to a wonderful career. This was the second time I’d interviewed him. He was semi-retired, which is as much retirement as most geologists ever achieve. The love of rocks, fossils & science often becomes fun again in retirement.

Jay Batcha, President of the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society, was with me that day. I invited Jay because I knew he’d be interested, give me good moral support, help keep the conversation flowing and ask questions I missed.

About two decades ago, on a Saturday afternoon, I interviewed Sam Pickering in his home office in Macon, Georgia. Sam stood as the Georgia State Geologist from 1972 through 1978 and had initiated an unprecedented wave of field research which continued well into the 1990s. Sam went on to a wonderful career. This was the second time I’d interviewed him. He was semi-retired, which is as much retirement as most geologists ever achieve. The love of rocks, fossils & science often becomes fun again in retirement.

Jay Batcha, President of the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society, was with me that day. I invited Jay because I knew he’d be interested, give me good moral support, help keep the conversation flowing and ask questions I missed.

Sam was never an easy interview. He was a big, athletic man, with a big voice, a subtle mind, and wasn’t shy about voicing his opinion. He had a prickly streak. He did not suffer fools lightly. He was also a superb geologist and a superb scientist. If you questioned his conclusions you’d better have your facts & evidence organized and on hand or you might get an earful.

There’s an old story from his college years at the University of Tennessee that he was encouraged to go out for the football team. No surprise that he made the cut. But when he learned that practice was going to interfere with his science labs, he promptly dropped football.

There’s an old story from his college years at the University of Tennessee that he was encouraged to go out for the football team. No surprise that he made the cut. But when he learned that practice was going to interfere with his science labs, he promptly dropped football.

The interview went well and the three of us had a wonderful conversation wandering through many topics, but then the subject of Fernbank Museum and Sam’s personal collection of fossils and minerals came up; Sam’s mood instantly soured.

Sam had a long and active career which included a great deal of field work, he’d amassed a very respectable collection of Georgia fossils and minerals which he used for personal and state research. He wanted to see them safely cared for and put to work for the education of all Georgians. At retirement he donated the best and bulk of his collection to Fernbank. As Sam told the story; Fernbank lost much of the collection and trashed the rest. His opinion of Fernbank was poor, but I’ll not repeat here the language he used on that long-ago Saturday.

Some years later I learned that while a large part of the collection had indeed been lost, much of it remained. However, the all-important tags that identified specimens and where they’d come from had either been lost or jumbled together.

Scott Harris, the resident geologist at Fernbank Science Center, put forth the effort to recover, reorganize, and relabel the remaining specimens from Pickering and still maintains the Pickering collection.

Sam passed away in August of 2020. I attended his memorial service in Macon. I’m still of the opinion that Sam Pickering was probably one of the most influential State Geologist Georgia has ever known, he should stand proudly beside greats like Samuel W. McCallie (State Geologist 1908-1933).

Some years later I learned that while a large part of the collection had indeed been lost, much of it remained. However, the all-important tags that identified specimens and where they’d come from had either been lost or jumbled together.

Scott Harris, the resident geologist at Fernbank Science Center, put forth the effort to recover, reorganize, and relabel the remaining specimens from Pickering and still maintains the Pickering collection.

Sam passed away in August of 2020. I attended his memorial service in Macon. I’m still of the opinion that Sam Pickering was probably one of the most influential State Geologist Georgia has ever known, he should stand proudly beside greats like Samuel W. McCallie (State Geologist 1908-1933).

This was my first experience with failures in professional stewardship of research collections. I was frankly shocked. Sadly, it would not be my last.

Voorhies &

University of Georgia

For whatever reason, the research collection of fossils that Dr. Michael Voorhies assembled during the 1970s at the UGA Geology Department was never transferred into the Georgia Natural History Museum at UGA and the vast majority of it is now lost.

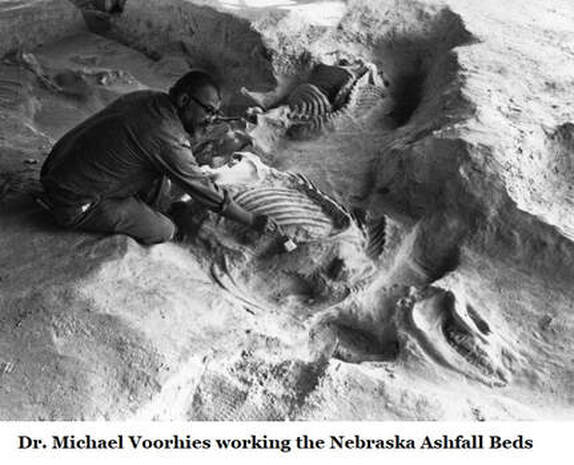

Do you recognize the name Dr. Michael R. Voorhies? He began is career at the University of Georgia where he did some solid southeastern paleontology. His fame emerged in 1971 while vacationing at his family home in Nebraska. He and his wife found a juvenile rhino skull weathering out of the ground and it turned out to be one of many victims from a 12-million-year-old volcanic ash kill-zone. The Nebraska Ashfall Fossil Bed were established as a state park in 1986. A herd of now-extinct rhinoceroses (Genus; Teleoceras) occur as well as horses, camels, dogs, birds, turtles, & one saber-toothed deer.

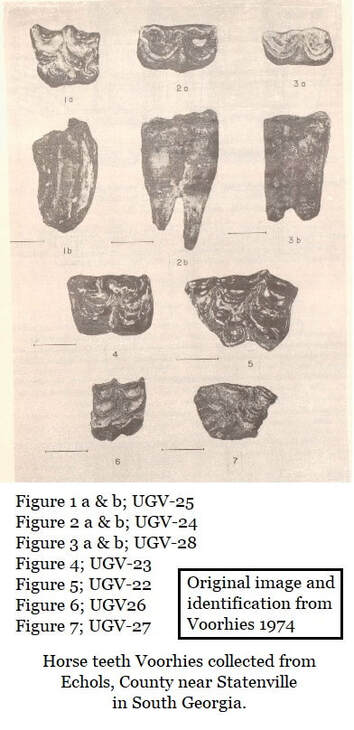

Voorhies left UGA in the mid-1970s to teach, continue research, and begin excavation into the ash beds. However, in 1974 he published a final flurry of scientifically important papers on Georgia’s vertebrate fossil record.

There’s been some question about what happened to Voorhies’ fossils when he left UGA despite evidence that he left the collection behind. To quote a 21/December/2021 letter from Dr. Byron Freeman (Director and Curator of Zoology, Georgia Natural History Museum). “We can only speculate about the fate of Dr. Voorhies’ material after he left the University. I queried eight faculty members associated with the department of Geology, many retired, regarding this issue, and none thought there was any Voorhies material left at the University, other than the reconstructed sloth placed in the Science Library in the early 1970s. They also were not aware of any catalogs left behind.”

There’s been some question about what happened to Voorhies’ fossils when he left UGA despite evidence that he left the collection behind. To quote a 21/December/2021 letter from Dr. Byron Freeman (Director and Curator of Zoology, Georgia Natural History Museum). “We can only speculate about the fate of Dr. Voorhies’ material after he left the University. I queried eight faculty members associated with the department of Geology, many retired, regarding this issue, and none thought there was any Voorhies material left at the University, other than the reconstructed sloth placed in the Science Library in the early 1970s. They also were not aware of any catalogs left behind.”

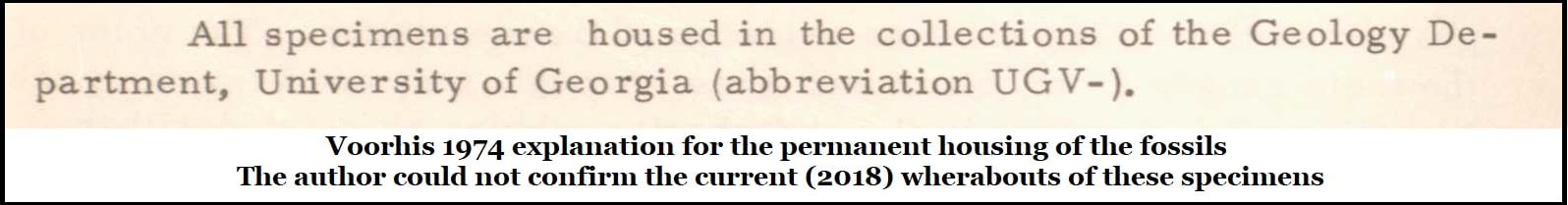

It would seem there’s some confusion at the University. Voorhies stated categorically in the 1974 papers that the fossils were cataloged into the UGA Geology Department collection.

“All specimens are housed in the collections of Geology Department, University of Georgia (catalog numbers UGV-)” (1), (2)

“The specimens are catalogued in the fossil collections of the Geology Department,

University of Georgia.” (3)

“All specimens are housed in the collections of Geology Department, University of Georgia (catalog numbers UGV-)” (1), (2)

“The specimens are catalogued in the fossil collections of the Geology Department,

University of Georgia.” (3)

Furthermore; in 1969 Voorhies reported a manatee tooth from the Tivola Limestone of Twiggs County. The tooth had been collected by experienced amateur Bill Christy and given to Voorhies for review, identification, and publication in the Georgia Journal of Science. Voorhies placed the tooth in the UGA collection as specimen# UGV-41. In 1982 researchers from the Smithsonian Institution, led by Daryl Domning, published a paper over the natural history of manatees and in their course of their research they’d called on UGA to inspect the tooth UGV-41. Upon inspection they overturned Voorhies ID and identified the tooth as a worn, adult entelodont tooth. This occurred after Voorhies had left UGA.

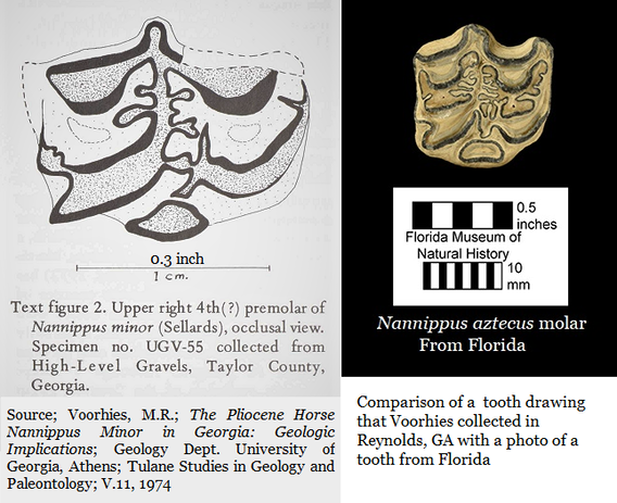

And just in case doubts linger… In 1974 Voorhies reported the unusual presence of two horse teeth, at least 5 million years old, in Taylor County near Reynolds, GA. He identified them as belonging to the small, three-toed horse Nannippus minor. He assigned the larger one as UGV-55 & the smaller one as UGV-56. (3)

Dr. Richard Hulbert is the Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History and a deeply experienced vertebrate paleontologist who’s done serious work here in Georgia. He led the team which described and named our proto-whale Georgiacetus vogtlensis in 1998.

Hulbert reports that during the late 1980s UGA loaned him the teeth Voorhies had collected so he could review them. Florida researchers had recovered a number of horse teeth from the northern part of their state and wanted to compare them with Voorhies’ teeth. Hulbert began by explaining that the horse species Nannippus minor had been reassigned as Nannippus aztecus then confirmed that the larger of the two teeth, UCV-55, was a molar from Nannippus aztecus. However, the smaller tooth was different, UGV-56 was incorrectly identified as a N. aztecus and was probably a Pseudhipparion simpsoni. He then safely returned the teeth to UGA. (for details see: 19A; Two Small Primitive Horses from Taylor County, Georgia.) Hulbert’s review of the teeth was more than a decade after Voorhies had left UGA.

This subsequent work by both Domning and Hulbert show conclusively that Voorhies fossils were still held by UGA, cataloged, and accessible to researchers long after Voorhies left. According to Freeman’s December 2021 letter UGA established the natural history museum in 1978 and it became the Georgia Natural History Museum, by an act of the Georgia state legislature in 1999. Why the scientifically important vertebrate fossils Voorhies had collected in Georgia and placed in UGA Geology Department collection, weren’t transferred to the natural history museum, remains a mystery. Clearly, if fossils were made available to outside researchers, they were cataloged, and the faculty knew where they were. Staff from other institutions certainly expected them to be available for review.

This subsequent work by both Domning and Hulbert show conclusively that Voorhies fossils were still held by UGA, cataloged, and accessible to researchers long after Voorhies left. According to Freeman’s December 2021 letter UGA established the natural history museum in 1978 and it became the Georgia Natural History Museum, by an act of the Georgia state legislature in 1999. Why the scientifically important vertebrate fossils Voorhies had collected in Georgia and placed in UGA Geology Department collection, weren’t transferred to the natural history museum, remains a mystery. Clearly, if fossils were made available to outside researchers, they were cataloged, and the faculty knew where they were. Staff from other institutions certainly expected them to be available for review.

The vast majority of Voorhies’ Georgia research collection is apparently lost. According to his December, 2021 letter Dr. Freeman only found one small box of marked “Statenville” during his search at the same time.

His December 2021 letter to me was in response to a November 2021 letter I’d written the Board of Regents. A year previously I’d had November 2020 email from Freeman when I’d inquired, once again, about comparing recently recovered specimens to items Voorhies’ had reported. Items I assumed as being held either at UGA or the natural history museum. On 18/Nov/2020 Freeman replied, “We have been looking for these early specimens that Michael collected and have not had much success locating them… I’ve not given up hope finding these fossils, however this is a long haul.”

His December 2021 letter to me was in response to a November 2021 letter I’d written the Board of Regents. A year previously I’d had November 2020 email from Freeman when I’d inquired, once again, about comparing recently recovered specimens to items Voorhies’ had reported. Items I assumed as being held either at UGA or the natural history museum. On 18/Nov/2020 Freeman replied, “We have been looking for these early specimens that Michael collected and have not had much success locating them… I’ve not given up hope finding these fossils, however this is a long haul.”

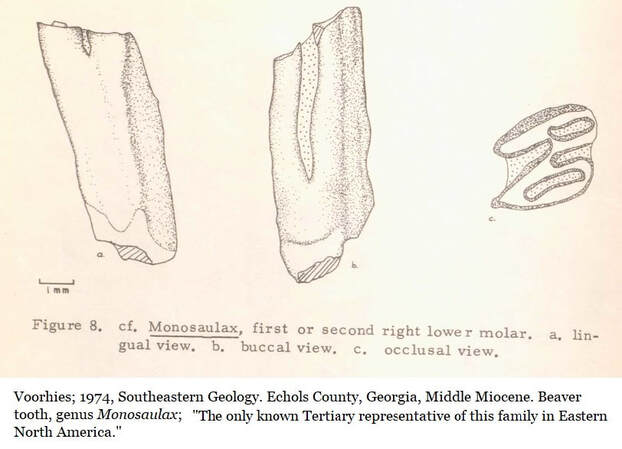

A year later there was still no reported progress on finding Voorhies specimens. That’s when I wrote the Board of Regents and they forwarded my concerns to Freeman. Their involvement inspired the discovery of the “small box marked Statenville” which is likely material from Voorhies 1974 Echols County paper (2) but Freeman did not report the box’s contents. There were scientifically important fossils reported in that paper, including a canid toe bone and unidentified teeth from a larger horse which should be reviewed by Dr. Richard Hulbert, who has expertise in the fossil beds along the Georgia/Florida border. Our knowledge of horse evolution in North America has greatly expanded since 1974.

If that Statenville box is the material reported in 1974 from Echols County it might contain the following fossils;

Beaver small molar

Dog Canid toe bone

Manatee Several rib sections

Horse teeth Genus Merychippus

Larger horse Teeth from an unidentified larger horse

Rhino Several bones from Teleoceras

200 assorted shark teeth

If that Statenville box is the material reported in 1974 from Echols County it might contain the following fossils;

Beaver small molar

Dog Canid toe bone

Manatee Several rib sections

Horse teeth Genus Merychippus

Larger horse Teeth from an unidentified larger horse

Rhino Several bones from Teleoceras

200 assorted shark teeth

For decades a reconstructed giant sloth which Voorhies had collected from Watkins Quarry near Brunswick, Georgia was on display at the UGA library. (5) It was taken down in 2016 and, I hope, stored in such a way that researchers can access it. Voorhies published a short essay on this in the Georgia Journal of Science in 1971 where he reported finding partial skeletons of two adult and one juvenile Eremotherium sloths; “gigantic megatheriid ground sloth” to quote Voorhies’ paper. Voorhies observed that the adult male seemed 50% larger than the female and the find suggested these sloths travelled in family groups. No further work has been done in this, and apparently such work cannot proceed without the additional fossils he recovered from Watkin Quarry.

Dr. Robert K. McAfee is an expert on sloths and stood as lead author on a 2021 paper reporting a new species of sloth from the Dominican Republic. McAfee is deeply immersed in the science of sloths… He reports that research from South America looked at sexual dimorphism in Eremotherium, but the research was hindered since sex is rarely assigned to fossil specimens. However, in many modern members of the Xenarthra clade, which includes sloths, the females are larger. (Personal communication)

Clearly, the loss of Voorhies UGA collection has damaged Georgia vertebrate paleontology research in many ways. It is a sad fact that retiring Georgia paleontology researchers don’t even consider donating their collection to the Georgia Natural History Museum.

Currently UGA and the Georgia Natural History Museum are trying to secure funding for new facilities. All things considered I cannot support the further financial investment, much less expanded financial investment, into this institution. There are other university related museums here in Georgia which have a far better track record with education and stewardship of our natural history.

State of Georgia &

Georgia Geological Survey Collection

The Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished in 2004 nearly a decade of ever decreasing budgets. The collection of research specimens they’d amassed was reportedly stored temporarily in a rundown warehouse with a failing roof. Parts of the collection were reportedly actually left outside on racks.

State of Georgia &

Georgia Geological Survey Collection

The Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished in 2004 nearly a decade of ever decreasing budgets. The collection of research specimens they’d amassed was reportedly stored temporarily in a rundown warehouse with a failing roof. Parts of the collection were reportedly actually left outside on racks.

In two separate moves, much of the collection was given to Tellus Science Museum as a alternative to being discarded. This did not include any fossils, but mineral samples and documents. Tellus has since reorganized, cataloged, and labeled the samples. They are being cared for, Tellus has done a superb job with this.

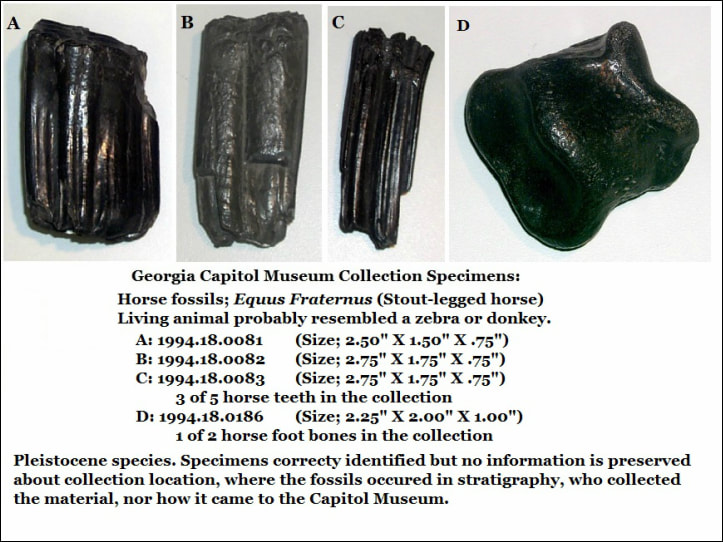

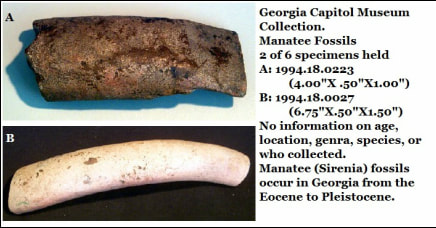

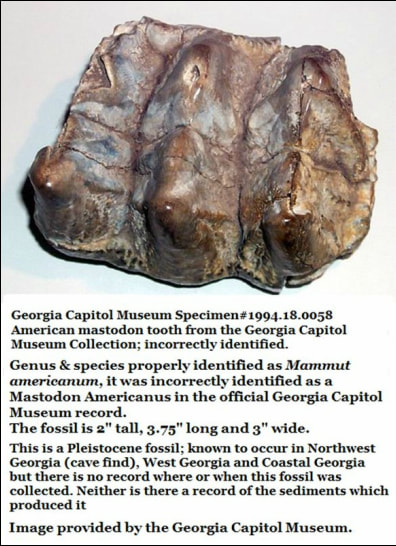

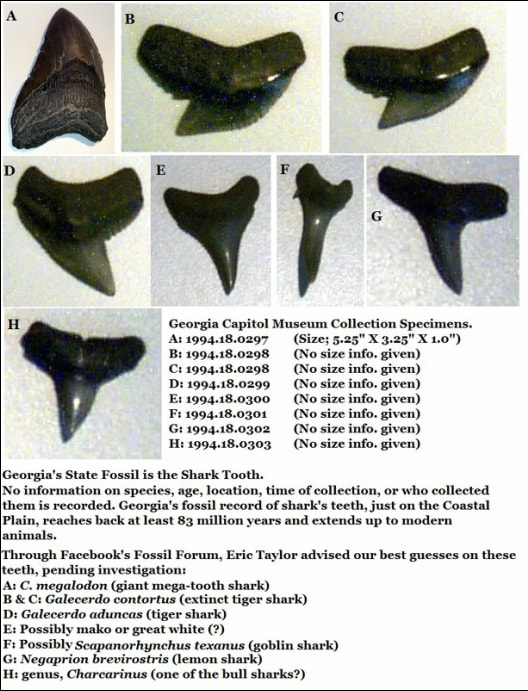

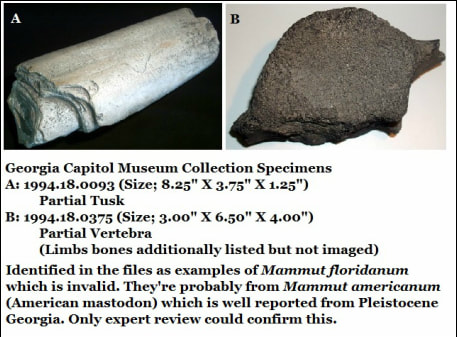

According to former state survey employees, display-quality vertebrate material was transferred from the Georgia Geological Survey to the State Capitol Museum. In 2012 fifty-four pdf files about these fossils were shared with me. At some point there’d been an attempt to digitize the collection and a great deal of info was lost. (See Section 24; Georgia Geologic Survey, A Bit of History; of this website.)

Of the files shared, all were partial with little to no information about the location of the find, its position in the stratigraphy, or even its general age. Several specimens were completely misidentified. There were images, but no scale reference was provided which makes their value questionable.

A few years ago a friend of mine, knowledgeable about paleontology, went to work as a volunteer at the Capitol Museum and hoped to address some of these issues. Bureaucracy, zero budget, and politics made the work impossible causing him to throw his hands up in frustration.

This is a state resource which the state government has taken responsibility for. While I do thank and acknowledge their efforts for preserving the Agomphus oxysternum turtle carapace fossils described by Edward Drink Cope in 1877, (see Section 9A: The Georgia Turtle; of this website) the Georgia Capitol Museum is hardly setting the gold-standard for preservation and stewardship.

Volunteers

The Macon Museum of Arts and Sciences had a fine mineral & fossil collection donated by a patron, this was kept on display and well maintained for many years. They finally decided to take it down and repurpose the display area and perhaps increase ticket sales. Volunteers, apparently untrained in the importance of specimen tags, were assigned the task of boxing the specimens up. The tags were apparently discarded. Years later an old friend of mine, the very same Jay Batcha of the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society, went to work at the Museum of Arts & Sciences. It was largely his expertise and efforts which re-organized, re-identified and corrected the collection when the museum decided to put it back on display. We’ll done, Jay!

Corporate Collections

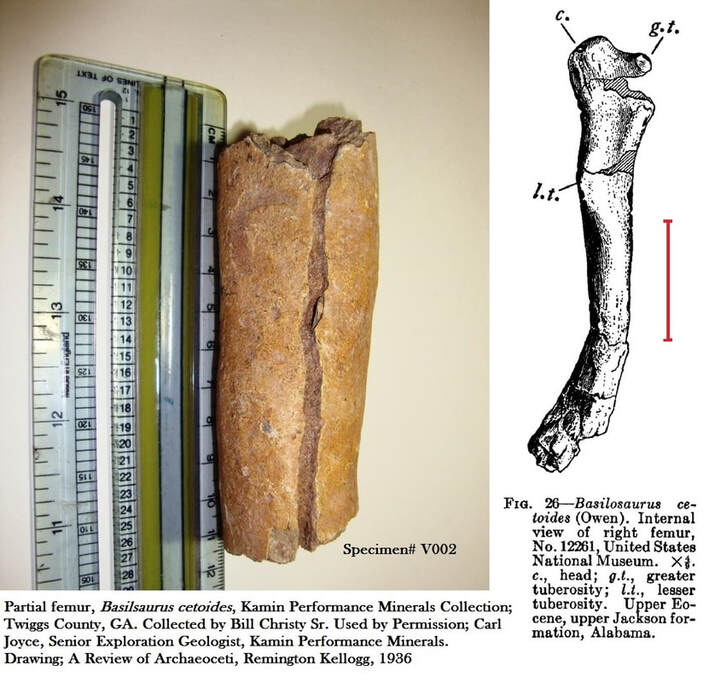

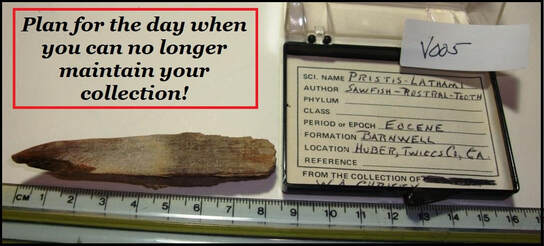

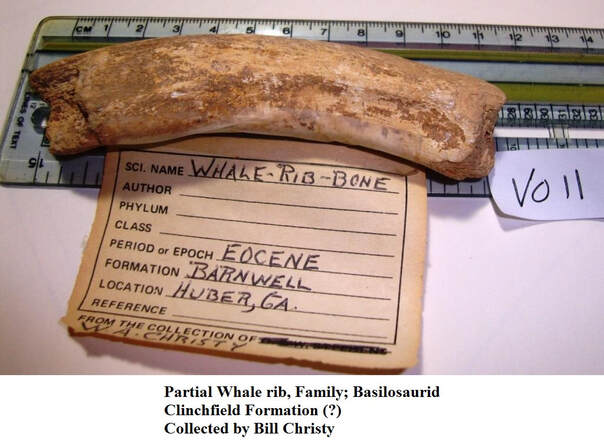

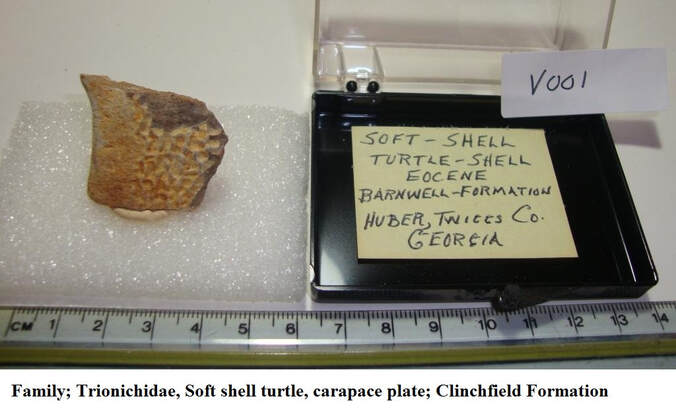

Back in 2014 Kamin Performance Minerals and asked me to review and organize their fossil collection. This collection had been assembled by advanced amateur Bill Christy thirty years earlier when Kamin was J. M. Huber Corporation. It had sat in boxes in their shop for years, maybe decades, much of it was missing, tags had been lost and many fossils were damaged.

Kamin hoped to start using the collection in talks at schools; kaolin mines are often sources for fossils and Kamin hoped to do a little community outreach. As much as possible Christy’s original tags were preserved. Since tags were missing and formations had been reassigned since the collection was assembled a best guess about the source matrix was often the best that could be done. Tivola Limestone occurs in the area, there’s also were Twiggs Clay, and in some spots the Clinchfield Formation.

Knowing that they were going to be used at public schools and that the fossils would be unpacked, put on display, then packed up again in a matter of a few hours, the question became how do to insure they weren’t jumbled together again and their tags separated from the specimens.

The answer was to assign a number to each sample and take a pic or two with a scale where the number showed in the image. These were then assembled into a simple to use catalog with thumbnails and brief descriptions. Since there were only about 50 specimens, the catalog file was small enough to email. Otherwise, it would have been put on a thumb-drive.

There are other ways to solve the problem. Jay Batcha, whom I introduced earlier, has a wonderful travelling fossil collection which can cover your typical 6ft folding table.

Cataloging

There are fully staffed and funded, university-based natural history museums in Georgia today, run by professionals, whose scientifically important fossil collections are not cataloged. Collections which include multiple first-reported or oldest-known specimens for Georgia, the Southeast, and North America. Since the collection is not cataloged and tracked, it cannot be properly maintained and safeguarded. If the collection were lost or destroyed, there would be little to no record of it.

Preserving a Collection

Plan for the day when you can no longer maintain your collection, if you’re an amateur who collects for a hobby, an academic or professional collecting for research, or an institution whose purpose is stewardship of natural history, plan for the day when you can no longer maintain your collection!

Identification Number

Assign a number to your specimen. If possible, write that number on the specimen with a paint pen. Your numbering system can be as simple as sequential numbers, alpha-numeric numbering or date-acquired based numbering. On the Kamin collection sequential numbers were used starting with a “V” for vertebrate and “IV” for invertebrate.

Plan for the day when you can no longer maintain your collection, if you’re an amateur who collects for a hobby, an academic or professional collecting for research, or an institution whose purpose is stewardship of natural history, plan for the day when you can no longer maintain your collection!

Identification Number

Assign a number to your specimen. If possible, write that number on the specimen with a paint pen. Your numbering system can be as simple as sequential numbers, alpha-numeric numbering or date-acquired based numbering. On the Kamin collection sequential numbers were used starting with a “V” for vertebrate and “IV” for invertebrate.

Identification Tags

Your fossil has a number. You know what your specimens are, where they came from, what formation produced them, when they were acquired, and whether you personally collected or purchased them. RECORD ALL OF THIS ON A SMALL TAG AND PUT THE FOSSIL AND TAG TOGETHER! It is important that you’re honest, don’t claim to have collected something you purchased. This is the identification tag and it should go wherever the specimen goes. They can be neatly hand-written, typed, or created on a computer. Some people laminate them. The tag is at least as valuable as the fossil, without the tag the fossil becomes a mere curiosity, with a proper tag it has scientific value.

Image your specimen

Your specimen has a number and a tag, now get your phone and take some pics of the fossil, image it in 2 or 3 views, provide something for size comparison. A ruler of some kind is best and include enough of the ruler so that people will know if the scale is in inches or centimeters. Most USA rulers have both. Other things can be used for scale but make sure it is something universal. Coins are often used, but this is a poor choice since they aren’t universal. If someone in the UK used a one-pound coin as a scale, I’d be lost. Is it the size of an American dime, nickel, quarter, or one dollar coin?

Your fossil has a number. You know what your specimens are, where they came from, what formation produced them, when they were acquired, and whether you personally collected or purchased them. RECORD ALL OF THIS ON A SMALL TAG AND PUT THE FOSSIL AND TAG TOGETHER! It is important that you’re honest, don’t claim to have collected something you purchased. This is the identification tag and it should go wherever the specimen goes. They can be neatly hand-written, typed, or created on a computer. Some people laminate them. The tag is at least as valuable as the fossil, without the tag the fossil becomes a mere curiosity, with a proper tag it has scientific value.

Image your specimen

Your specimen has a number and a tag, now get your phone and take some pics of the fossil, image it in 2 or 3 views, provide something for size comparison. A ruler of some kind is best and include enough of the ruler so that people will know if the scale is in inches or centimeters. Most USA rulers have both. Other things can be used for scale but make sure it is something universal. Coins are often used, but this is a poor choice since they aren’t universal. If someone in the UK used a one-pound coin as a scale, I’d be lost. Is it the size of an American dime, nickel, quarter, or one dollar coin?

Physical Storage

The best set-up here I’ve ever seen is Jay Batcha’s mobile display. I introduced my friend Jay earlier in the text. Jay has an outgoing personality and is a long-time officer of the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society, so Jay often speaks or does exhibits here and there. If you get a chance to see him exhibit somewhere, go, it’s always worth your time.

Each of his mobile collection specimens has an individual box and two tags, one tag stays in the specimen’s box and the other goes on display with the specimen. The individual boxes are sized to the specimen. He then stores the individual boxes in flats by specimen type. It takes Jay just a bit longer to set-up and repack his mobile display, but when he finishes everything is stowed, safe and properly organized. He’s ready for his next exhibit. Impressive!

Creating A Catalog

So you have your specimens numbered, tagged, imaged, & stored. Create a catalog. You can use Microsoft Word or whatever program you wish as long as you can manipulate both images and text. You don’t need big, beautiful images in your catalog, low-res small images are fine as long as they are large enough to see the fossil and it’s number. You want to try to keep the catalog file small enough to email at need. Remember, you might not be the only one looking at this catalog, a stranger may be using it, so keep it organized, neat and simple to navigate.

The Value of Your Collection

Unless you have thoroughly established yourself among the academics and museum curators, your collection is not going to end up in a museum or university. As we have seen in the above pages, such destinations aren’t necessarily the safest. Additionally, donated specimens sometimes aren’t properly valued. If you give someone a free car, it might not be as maintained as the car the car they spent 3 years paying for.

That leaves some options.

There are fossil and mineral dealers out there who will purchase a well-organized collection, you’ve created a catalog, so you have something to show them. You won’t get rich, but this can be a source for some income. There is absolutely nothing wrong with selling legally acquired fossils or minerals. Mines do it every day. But bear in mind that dealers will very likely break your collection up, but that’s okay too. They have paid for it, so they value it. The same can be said for the dealer’s customers. They’ve paid hard earned cash for your fossils; they’ll value them.

Local Board of Education

You could also donate it to the science office of the local board of education, a properly identified and cataloged collection has educational value. Going down this route will likely mean that your collection won’t last more than a few years before it is lost or scattered to the winds… Kids will be kids and teaches tend to be busy. But putting fossils in kid’s hands can be a powerful thing. That’s how future paleontologist are created. What better end to a collection than inspiring a child to pursue science!

References

- Voorhies, M. R.; Pleistocene Vertebrates with Boreal Affinities in the Georgia Piedmont, Quaternary Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, Pg 85-93, March 1974.

- Voorhies, Michael R., Late Miocene Terrestrial Mammals Echols County, Georgia

Geology Department, University of Georgia, Published in Southeastern Geology, 1974 - Voorhies, M.R.; The Pliocene Horse Nannippus Minor in Georgia: Geologic Implications; Geology Dept. University of Georgia, Athens; Tulane Studies in Geology and Paleontology; V.11, 1974

- Domning. Daryl P.; Morgan, Gary S.; Ray, & Clayton E.; North American Eocene Sea Cows(Mammalia: Sirenia), Smithsonian Contributions to Paloebiology, #52, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 1982

- Voorhies; M.R.; The Watkins Quarry, A New Late Pleistocene Mammal Locality in Glynn County, Georgia; Bulletin of the Georgia Academy of Sciences, 29, Pg128, 1971