14P: Historic Rich Hill

Crawford County, GA

By Thomas Thurman

Filed: 10/May/2021

Brilliant Red Sand &

Abundant Fish Teeth.

“Brilliant red sand capping the hill…” is a quote from the 1911 report of Rich Hill in Crawford County, Georgia. This sand, stained by iron oxidation, is certainly interesting but a bit further down in the 1911 description you encounter; “…Fish teeth are also abundant in places.” (1) Abundant fish teeth suggest shark teeth.

Abundant Fish Teeth.

“Brilliant red sand capping the hill…” is a quote from the 1911 report of Rich Hill in Crawford County, Georgia. This sand, stained by iron oxidation, is certainly interesting but a bit further down in the 1911 description you encounter; “…Fish teeth are also abundant in places.” (1) Abundant fish teeth suggest shark teeth.

Preservation?

Rich Hill in Crawford County is unquestionably historic. But recently a question was asked if it’s worthy of preservation? That’s a different matter. The problem is, there is surprisingly little in the way of research over the site in 30 years and many in the Earth science community have simply forgotten about it.

Rich Hill in Crawford County is unquestionably historic. But recently a question was asked if it’s worthy of preservation? That’s a different matter. The problem is, there is surprisingly little in the way of research over the site in 30 years and many in the Earth science community have simply forgotten about it.

To my knowledge the last serious, professional-level fieldwork at Rich Hill was performed during a 1991 field trip of the Georgia Geologic Society led by Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick. Two superb field researchers, scientists, and invertebrate paleontologists. However the real focus of their 1991 fieldwork was identifying, dating and describing the surrounding Cretaceous & Paleocene sediments. Old sand and clay hills which had never been properly surveyed. The fossil rich Eocene deposits of Rich Hill sit like a young island surrounded by older deposits. (6)

So is there sufficient public or scientific support for preservation? We simply need more information. There are several invertebrate faunal list, or species lists, for Rich Hill, but no follow-up or additional work on shark teeth or other vertebrate fossils, show up in the literature.

So is there sufficient public or scientific support for preservation? We simply need more information. There are several invertebrate faunal list, or species lists, for Rich Hill, but no follow-up or additional work on shark teeth or other vertebrate fossils, show up in the literature.

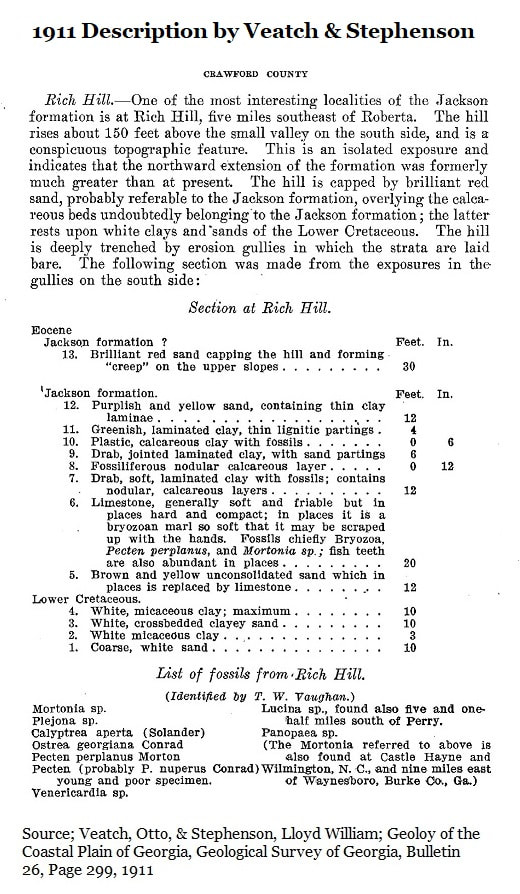

1911

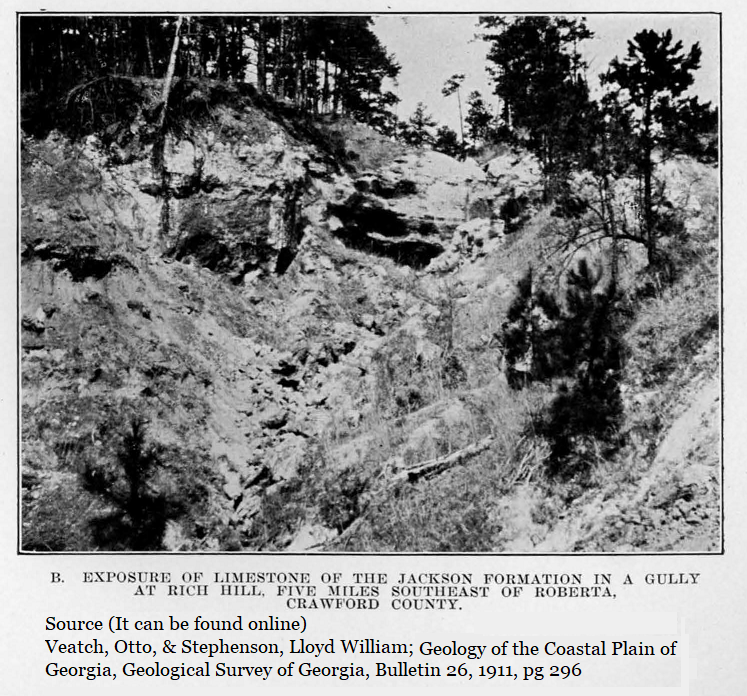

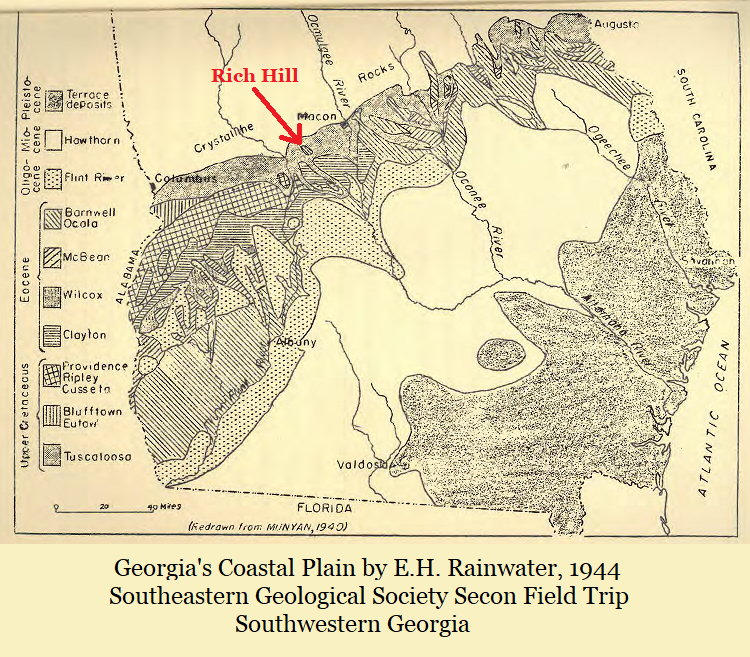

In 1911 Otto Veatch and Llyod W. Stephenson published an extensive geologic survey of Georgia’s Coastal Plain. To my knowledge this is the earliest mention of Rich Hill and its fossils. Veatch and Stephenson were working together as a joint project of the Georgia Geologic Survey and the USGS performing an initial assessment of the Coastal Plain’s paleontology and geologic resources. Rich Hill stands about 20 air miles southwest of Macon and is one of the northernmost fossil beds on the Coastal Plain. It is a natural first stop for researchers travelling south from Atlanta.

In 1911 Otto Veatch and Llyod W. Stephenson published an extensive geologic survey of Georgia’s Coastal Plain. To my knowledge this is the earliest mention of Rich Hill and its fossils. Veatch and Stephenson were working together as a joint project of the Georgia Geologic Survey and the USGS performing an initial assessment of the Coastal Plain’s paleontology and geologic resources. Rich Hill stands about 20 air miles southwest of Macon and is one of the northernmost fossil beds on the Coastal Plain. It is a natural first stop for researchers travelling south from Atlanta.

At just over 700 feet above sea level Rich Hill is the highest point in the immediate area. A drive along Highway 42 follows rolling hills and gifts some dramatic outcrops and sweeping views as it wanders through the rugged, sandy, Fall Line hills. The Fall Line Hills occur between the Fall Line and the Fort Valley Plateau.

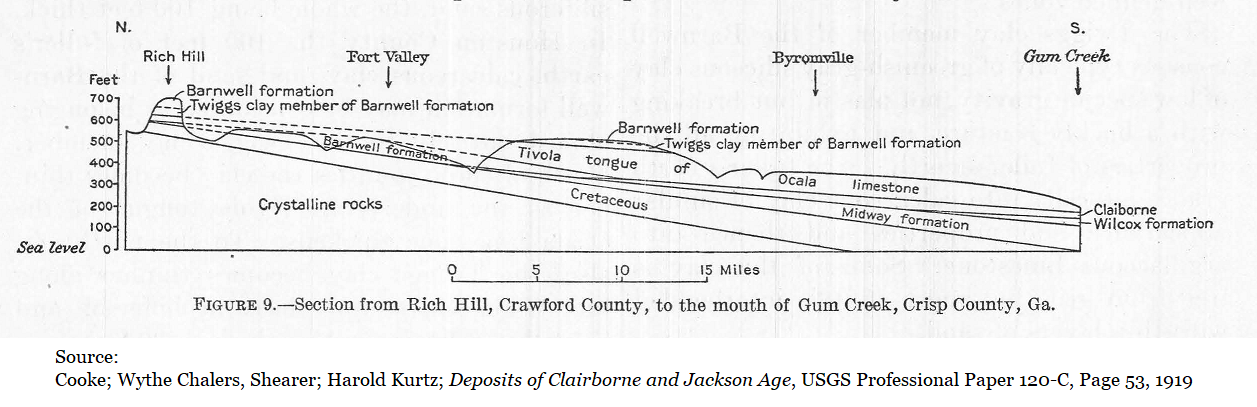

Rich Hill, which lies south of the state highway, is locally distinct because its capped, like an island which has lost its sea, by Eocene age sediments roughly 34 million years old. The surrounding sands and clays underlying the Eocene fossils beds Cretaceous aged, roughly twice as old at 68 million years.

There is such an abundance of Cretaceous sand in the Fall Line Hills that multiple sand mines have operated in the area for decades.

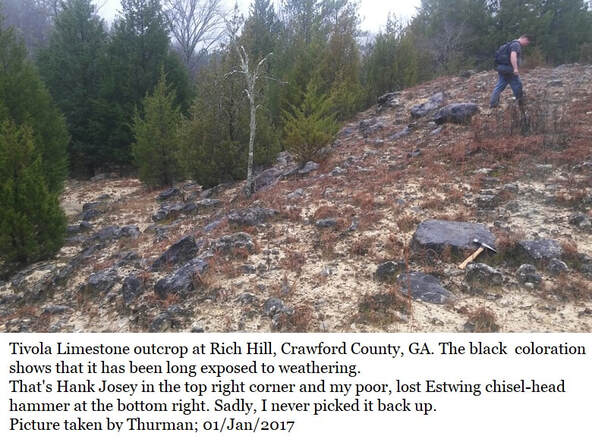

One of the fossil rich Eocene sediments of Rich Hill is the Tivola Limestone, In 1943 C. Wythe Cooke, described it thusly; “The (Tivola) Limestone represents the deposits of an invading sea that transgressed beyond the shore line of the preceding epoch and laid its sediments uncomformably on whatever older formations lay in its path.” (2)

In the last 60 million years there have been dozens of times when sea levels rose and coastlines transgressed far inland. There were times when such high sea levels lingered for millions of years. So yes, Rich Hill has been an island multiple times in the geologic past.

To quote a 2009 paper from Biological Reviews; "Over the last 1.8 million years, North America has been subjected to no less than 27 glacial intervals." (12) That means sea levels risen & fallen (glaciers have advanced & retreated) in North America 27 times in the last 1.8 million years.

To quote a 2009 paper from Biological Reviews; "Over the last 1.8 million years, North America has been subjected to no less than 27 glacial intervals." (12) That means sea levels risen & fallen (glaciers have advanced & retreated) in North America 27 times in the last 1.8 million years.

Fossil Beds

Interestingly, Rich Hill’s three fossil bearing formations are very well known and occur intermittently in Houston County, Twiggs County and Wilkinson County. Even the earliest researchers observed this and realized that these formations were continuous at some point, but weathering or erosion erased vast quantities of clay, sand and limestone. This left our current scattered deposits.

Interestingly, Rich Hill’s three fossil bearing formations are very well known and occur intermittently in Houston County, Twiggs County and Wilkinson County. Even the earliest researchers observed this and realized that these formations were continuous at some point, but weathering or erosion erased vast quantities of clay, sand and limestone. This left our current scattered deposits.

Sadly no list of vertebrate species has ever been assembled for the Rich Hill, but several invertebrate lists have been created which we’ll be review. Invertebrates are useful in dating sediments. A vertebrate list offers a glimpse into the health & diversity of the environment represented by a deposit.

Access

Veatch & Stephenson’s 1911 visit was only the beginning for researchers; for a few decades the hill became a stop for many earth scientists.

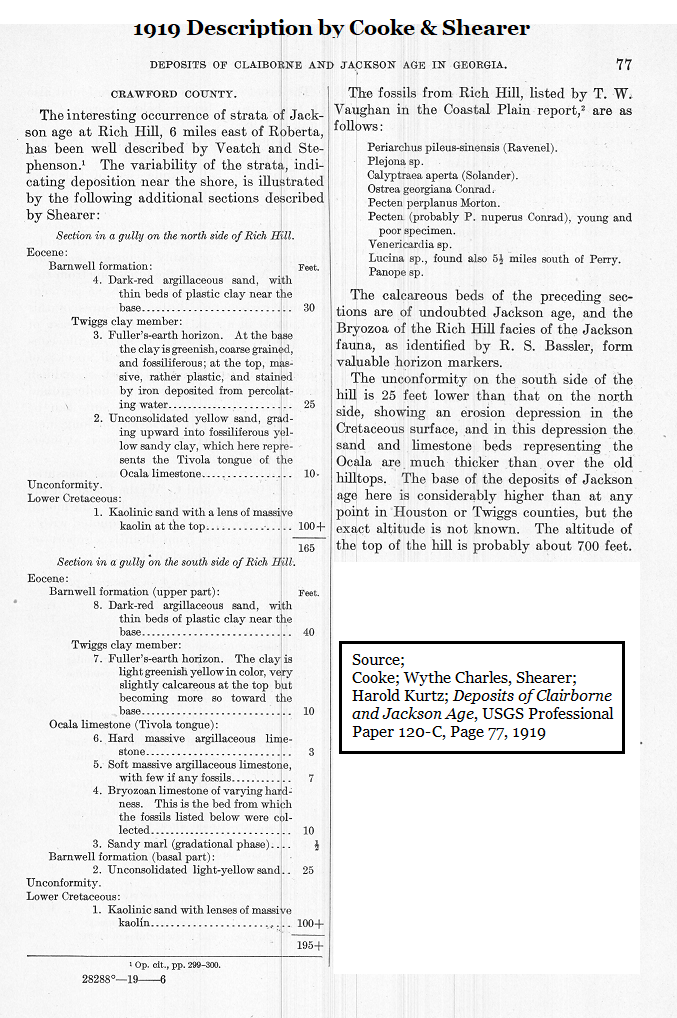

In 1919 Charles Wythe Cooke & Harold Kurtz Shearer published their USGS report on Eocene sediments in Georgia. (3) The Eocene spans from 33.9 to 55.8 million years ago. Cooke and Shearer were looking specifically at the more recent end of that time span. Rich Hill was their first stop and they used the location as a standard for Eocene deposits, comparing the Crawford County species to similar fossil deposits they encountered further south.

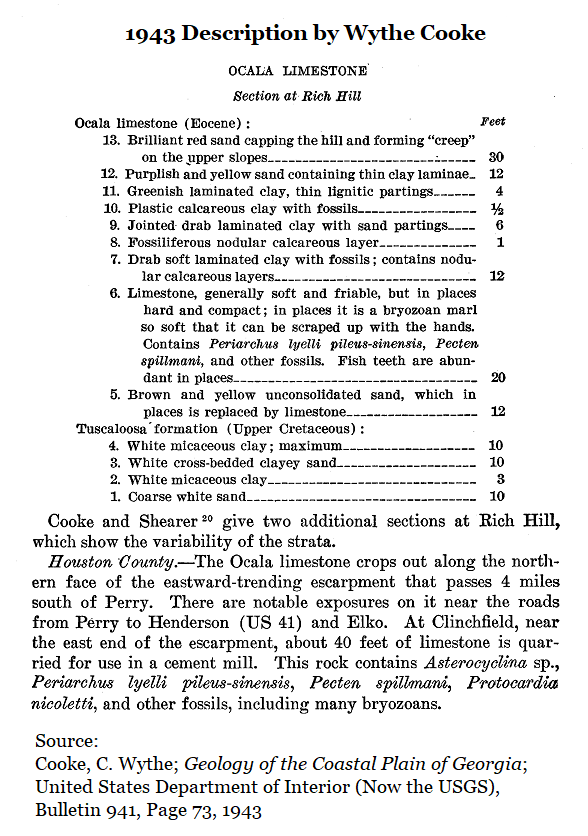

Cooke would report on Rich Hill again in his 1943 report on the Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia for the United State Geological Survey. (2)

Veatch & Stephenson’s 1911 visit was only the beginning for researchers; for a few decades the hill became a stop for many earth scientists.

In 1919 Charles Wythe Cooke & Harold Kurtz Shearer published their USGS report on Eocene sediments in Georgia. (3) The Eocene spans from 33.9 to 55.8 million years ago. Cooke and Shearer were looking specifically at the more recent end of that time span. Rich Hill was their first stop and they used the location as a standard for Eocene deposits, comparing the Crawford County species to similar fossil deposits they encountered further south.

Cooke would report on Rich Hill again in his 1943 report on the Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia for the United State Geological Survey. (2)

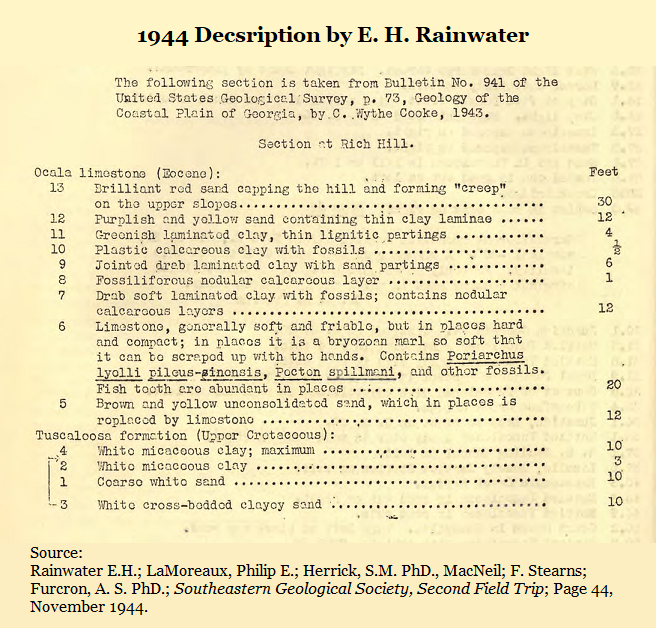

E.H. Rainwater included a stop at Rich Hill for the wide-ranging November 1944 field trip of the Southeastern Geological Society into southwest Georgia. (7)

Probably sometime during the 1980s some amateur rock clubs and societies gained access and collected at the site. I know of one knowledgeable amateur Jack Jones, a true Southern Gentleman and longtime member of the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society, who participated in a club dig at Rich Hill. I spoke to him about this in the mid-1990s, but even then, the Rich Hill dig had been decades earlier and his memory wasn’t clear. Sadly, Jack passed in 2020.

Probably sometime during the 1980s some amateur rock clubs and societies gained access and collected at the site. I know of one knowledgeable amateur Jack Jones, a true Southern Gentleman and longtime member of the Mid-GA Gem and Mineral Society, who participated in a club dig at Rich Hill. I spoke to him about this in the mid-1990s, but even then, the Rich Hill dig had been decades earlier and his memory wasn’t clear. Sadly, Jack passed in 2020.

Below:

Rich Hill Descriptions from

1911 * 1919 * 1943 * 1944

Rich Hill Descriptions from

1911 * 1919 * 1943 * 1944

In 1991 Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick included Rich Hill as Stop #2 on the Georgia Geological Society’s 26th annual field trip into the Fort Valley plateau and central kaolin district. (6) So at least at that time there was an access road which offered fairly easy access for a group of researchers.

Twenty-five years ago I was talking to a Crawford County native who’d been deer hunting at Rich Hill in the past, he talked about “pushing shark teeth up with the toe of my boot.” That’s not the kind of report you forget.

But for decades now, Rich Hill has notoriously difficult to access. The reason for this is simple, the location is private property leased by hunters and hunted nearly year-round. The best way to avoid tragic accidents is to strictly limit access. For good reasons, neither the hunters, nor the landowners are too keen on uninvited guests trespassing through the hills.

To my knowledge, no organized paleo group, geological society, informed amateur, academic, nor professional paleontologist has visited or published any report on Rich Hill fossils in 30 years, since the 1991. So the written histories is all we really have until the site is visited again and a report is published.

Modern Nomenclature for the Eocene Beds

There are three deposits reported from the hill which are known for fossils, all are late Eocene. In order, and using modern nomenclature they are:

There are three deposits reported from the hill which are known for fossils, all are late Eocene. In order, and using modern nomenclature they are:

- The Twiggs Clay

- The Tivola Limestone

- The Clinchfield Formation

The Twiggs Clay

Immediately beneath the cap of red sand is about 7 meters (23 feet) of the Twiggs Clay Member of the Dry Branch Formation (6). The Twiggs Clay dates to approximately 34.3 million years old. It is a widespread deposit of clay and silt laid down in a generally quite environment with minimal currents where clay minerals were able to settle out undisturbed. Limestone beds occur rarely in the Twiggs Clay in scattered locations. There is a 2-meter (8 foot) limestone bed in Oaky Woods, dense with fossils, which represents a tempest deposit.

It was once believed that the Twiggs Clay was of volcanic origin and was weathered volcanic ash. But during a field survey published in 1970 Sam Pickering showed that this was an error. “The writer finds it most difficult to believe that the sediment was once a volcanic ash embedding consistently abundant benthonic foraminifers or that the ash could have weathered so completely as to destroy any glass and volcanic minerals and leave the delicate hyaline foraminifer tests intact and shiny.” (5)

Vertebrate fossils occur in the Twiggs at many scattered locations, invertebrate fossils, especially bryozoans, often occur in dense quantities, but all fossils tend to be concentrated in localized outcrops and in most localities the Twiggs is nearly devoid of fossils.

In 1919 Cooke and Shearer reported two distinct beds of the Twiggs Clay at Rich Hill with both being fossiliferous. As no mention is made of species, the author assumes they were invertebrate fossils. In 1911 the Twiggs Clay was as yet undescribed, so Veatch and Stephenson didn’t mention it by name but seem to describe 4 beds. The 1911 description was essentially edited and re-used in both the 1943 and 1944 descriptions of the Twiggs Clay at Rich Hill.

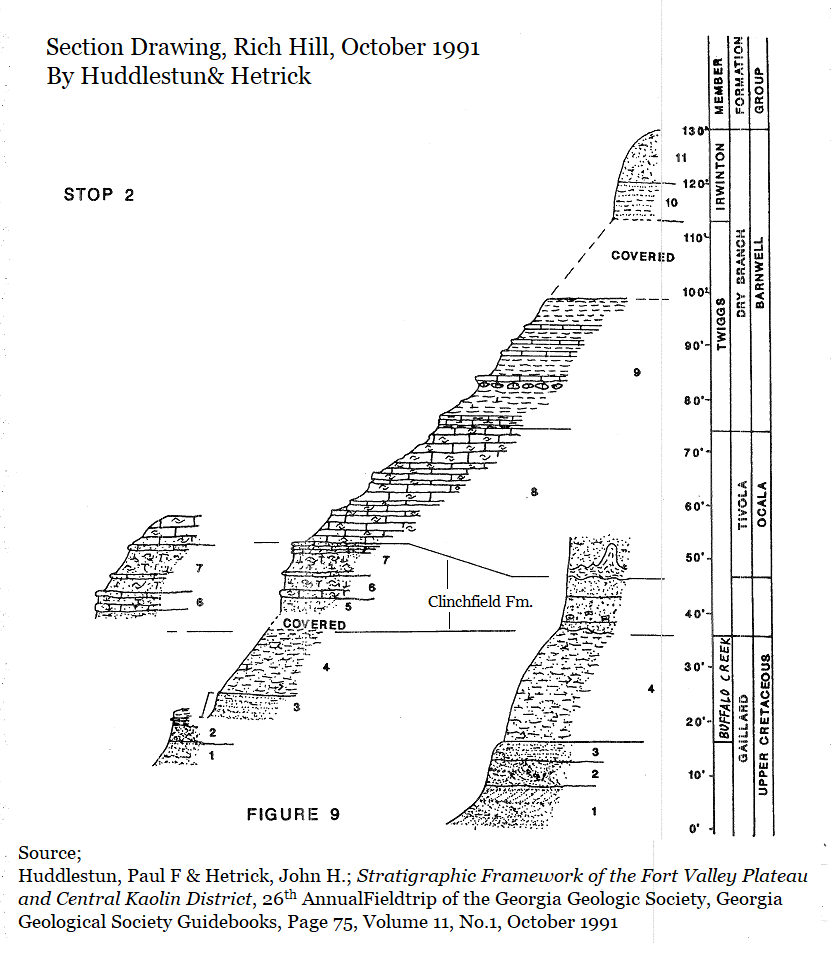

In 1991 Huddlestun & Hetrick published their research on the locale for a Georgia Geological Society field trip and this included a new section drawing & description using modern nomenclature. Huddlestun & Hetrick described a single bed of Twiggs Clay measured at 7 meters (23 feet) thick. (See Section 14D of this website for a partial list of Twiggs Clay vertebrates.)

Partial list of Twiggs Clay vertebrate species from various Georgia locations

Twiggs Clay Vertebrates reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate Great White (Warm Sea) Abundant

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Common

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Eosiren (species?) Manatee Rare

The American Museum of Natural History in New York

Twiggs Clay.GA Location: Huber Mine Pit #1

Reported by Gerard R. Case

Genus & Species Common name Finds

Lamna twiggsensis Mackerel shark 2 teeth

Ginglymostoma obliquum Nurse shark 2 teeth

Odontaspis acutissima Sand shark 3 teeth

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 3 snout teeth

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray 8 teeth

Twiggs Clay Vertebrates reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Common

Carcharias cuspidate Great White (Warm Sea) Abundant

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Common

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Abundant

Basilosaurus (species?) Early whale Very Rare

Eosiren (species?) Manatee Rare

The American Museum of Natural History in New York

Twiggs Clay.GA Location: Huber Mine Pit #1

Reported by Gerard R. Case

Genus & Species Common name Finds

Lamna twiggsensis Mackerel shark 2 teeth

Ginglymostoma obliquum Nurse shark 2 teeth

Odontaspis acutissima Sand shark 3 teeth

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 3 snout teeth

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray 8 teeth

The Tivola Limestone

Historically the Tivola Limestone was once known as the Ocala Limestone, but in 1986 Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick correctly re-assigned much of the traditional Ocala as the Tivola Limestone member of the Ocala Group. The two are of similar age but distinct. The name Tivola was derived from the extinct village and train station of Tivola in Houston County, about half a mile southeast of the Perdue Farms Plant on the Highway 247 spur in Houston County. The train station apparently once stood where AE Harris Rd crosses the railroad tracks.

The Tivola Limestone

Historically the Tivola Limestone was once known as the Ocala Limestone, but in 1986 Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick correctly re-assigned much of the traditional Ocala as the Tivola Limestone member of the Ocala Group. The two are of similar age but distinct. The name Tivola was derived from the extinct village and train station of Tivola in Houston County, about half a mile southeast of the Perdue Farms Plant on the Highway 247 spur in Houston County. The train station apparently once stood where AE Harris Rd crosses the railroad tracks.

The Ocala Limestone can still be seen in southwest Georgia.

In general the Tivola Limestone is rich in invertebrate material but rather poor in vertebrate fossils. Sand dollars, scallops, and especially bryozoans can occur in great numbers. It is an offshore, high energy, current driven deposit typically requiring some water depth, perhaps 100 ft. It was primarily formed by material “falling out” of a strong current. This would have been the mighty Suwannee Current which carved a great trough in South Georgia. (For more info see Section 8 of this website.)

In general the Tivola Limestone is rich in invertebrate material but rather poor in vertebrate fossils. Sand dollars, scallops, and especially bryozoans can occur in great numbers. It is an offshore, high energy, current driven deposit typically requiring some water depth, perhaps 100 ft. It was primarily formed by material “falling out” of a strong current. This would have been the mighty Suwannee Current which carved a great trough in South Georgia. (For more info see Section 8 of this website.)

The 1911 report of abundant fish teeth came from the Tivola Limestone. The entire quote states; “Limestone, generally soft and friable (easily crumbles) but in places hard and compact: in places it is a bryozoan marl so soft that it may be scraped up with the hands. Fossils chiefly Bryozoa, pecten perplanus, and Mortonia sp.; fish teeth also abundant in places.”

The fossil rich Tivola the largest limestone deposit occurring in Houston County, Ga. It has long been mined. In 1911 there were already “old” limestone quarries just south of Perry, GA (1) which still exist. To date the Tivola has produced two historically and scientifically important early whale fossils; in 1911 Veatch & Stephenson reported an important find in the Tivola of Bonaire and then in 1937 another was recovered which went on to become part of the displays at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington DC. (See Section 14C of this website for a more detailed description of the Tivola Limestone and a partial list of vertebrate fossils.)

Partial list of Tivola Limestone vertebrates from various Georgia locations.

Georgia Geologic Survey; Sam Pickering 1970 (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Rare

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Common

Basilosaurus cetoides Early whale Very Rare

Siren (species?) Manatee (rib frags) Rare

Dr. Michael Voorhies University of Georgia (1982)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Entelodont (Genus?) Terminator pig Very Rare

Recently reported by Doug Holder, Cemex, Clinchfield, GA

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Carcharocles auriculatus Megatooth shark Rare

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Collected & donated by Bill Christy

Genus & Species Common name Specimen - County

Carcharhinus (species?) Requiem shark Tooth- Twiggs

Cretolamna (species?) Mackerel shark Tooth- Twiggs

Galeorhinus (species?) Hound shark Tooth- Twiggs

Hemipristis (species?) Snaggletooth shark Tooth-Twiggs

Odontaspis (species?) Sand Shark Tooth-Twiggs

Sphyraena (species?) Barracuda Tooth- Twiggs

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Barnwell Formation vertebrates (Land Mammal)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen

Leptotragulus medius Camelid Tooth & jaw

Jefferson Co. Reported by McCallie

Georgia Geologic Survey; Sam Pickering 1970 (Bulletin 81)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Lamna apppendiculata Mackerel Shark Rare

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Rare

Galeocerdo latidens Tiger Shark Rare

Myliobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Common

Basilosaurus cetoides Early whale Very Rare

Siren (species?) Manatee (rib frags) Rare

Dr. Michael Voorhies University of Georgia (1982)

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Entelodont (Genus?) Terminator pig Very Rare

Recently reported by Doug Holder, Cemex, Clinchfield, GA

Genus & Species Common name Frequency

Carcharocles auriculatus Megatooth shark Rare

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Collected & donated by Bill Christy

Genus & Species Common name Specimen - County

Carcharhinus (species?) Requiem shark Tooth- Twiggs

Cretolamna (species?) Mackerel shark Tooth- Twiggs

Galeorhinus (species?) Hound shark Tooth- Twiggs

Hemipristis (species?) Snaggletooth shark Tooth-Twiggs

Odontaspis (species?) Sand Shark Tooth-Twiggs

Sphyraena (species?) Barracuda Tooth- Twiggs

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (online catalog)

Barnwell Formation vertebrates (Land Mammal)

Genus & Species Common name Specimen

Leptotragulus medius Camelid Tooth & jaw

Jefferson Co. Reported by McCallie

The Clinchfield Formation

The Clinchfield Formation is naturally exposed on Rich Hill as a yellow/brown sand with invertebrate fossils. The Clinchfield is Georgia’s most productive source of vertebrate fossils, especially sharks teeth. It is exposed very rarely as fossiliferous sand, there are a few other natural outcrops but these are hardened, silicified deposit rich in shelly fossils and gastropods but seemingly lacking vertebrate material.

The Clinchfield Formation

The Clinchfield Formation is naturally exposed on Rich Hill as a yellow/brown sand with invertebrate fossils. The Clinchfield is Georgia’s most productive source of vertebrate fossils, especially sharks teeth. It is exposed very rarely as fossiliferous sand, there are a few other natural outcrops but these are hardened, silicified deposit rich in shelly fossils and gastropods but seemingly lacking vertebrate material.

There is one such hilltop on the county line of Bibb’s & Twiggs County, know as Christy Hill by local amateurs it is capped by hard chert, silicified Clinchfield Formation. This site has produced a surprising quantity of small, thumb sized gastropods and several shelly fossils and some dense, pure jasper often seen in seams in the rock, but not a single shark tooth. (13)

However, Georgia’s Clinchfield Formation has produced more than 9,700 scientifically reported vertebrate fossils scattered among about 50+ species of sharks, bony fish, reptiles, marine mammals, terrestrial mammals & one bird. These were all reported from mines in either Houston County or Wilkinson County. Such a wealth of material makes the Clinchfield our state’s richest source of vertebrate material.

To my knowledge, no vertebrate fossils have ever been reported from Rich Hill. Was the toe of that hunter’s boot in the Clinchfield Sand? This is an issue that begs to be addressed.

The Clinchfield is a coastal deposit sometimes influenced by rivers, quartz sand is always involved to some degree. But in places the Clinchfield is a shell hash of fossils, it is named for Clinchfield, Georgia which is a tiny town in Houston County 7 miles southeast of Perry.

In 1970 Sam Pickering was researching the Clinchfield Formation and reported that he’d observed "reeflike" accumulations of articulated oysters in their growth positions. (5) The species he observed was Crassostrea gigantissima, this oyster genus typically tolerates being exposed at low tide.

“Reef-like accumulations of articulated oysters.” Pickering reported and collected some samples to deliver into the hands of Stephen M. Herrick, a biostratigrapher with the USGS. In 1972 Herrick published a paper reporting the contents of the Crassostrea gigantissima Pickering had given him. He reported the 50+ species of foraminifera fossils found trapped inside the sealed oysters. Identifying these species gave a date of between 35.42 to 36.18 million years old. (See Section 14B of this website for details.)

Partial List of Clinchfield Formation shark teeth from other locations in Georgia.

This list does not include other vertebrates

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency Reporting

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 492 teeth Westgate

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Shark Abundant Pickering*

Carcharias hopei Sand Tiger Shark 296 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias hopei Sand Tiger shark 922 teeth Westgate

Carcharias koerti Sand Tiger Shark 123 teeth Parmley

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth Parmley

Carcharodon auriculatus Giant toothed shark 2 teeth Westgate

Dasyatis (sp) Stingray 53 teeth Westgate

Edaphodon (sp) 1st SE Chimaera Extremely Rare Parmley

Galeo latidens Tiger shark 219 teeth Westgate

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth Parmley

Galecerdo latidens Tiger Shark Abundant Pickering*

Ginglymostoma serra Nurse shark 13 teeth Westgate

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth shark 170 teeth Westgate

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth Parmley

Heterodontus (sp) Angel Shark 1 Tooth Parmley

Isurus (sp) Mako shark 4 teeth Westgate

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth Parmley

Lamna (sp) Porbeagle shark 124 teeth Westgate

Lamna Appendiculate Mackerel shark Common Pickering*

Mustelus vanderhoefti Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth Parmley

Myliobatis (sp) Eagle Ray Abundant Pickering*

Myliobatis (sp) Eagle ray 8 dental batteries/284 teeth Westgate

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth Parmley

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth Parmley

Negaprion gibbesi Lemon shark 1538 teeth Westgate

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth Parmley

Physogaleus (sp) Carchrhinid 19 teeth Westgate

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth Parmley

Pristis (sp) Sawfish Very rare Pickering*

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 238 rostral teeth Westgate

Raja (sp) Skate 4 skutes Westgate

Rhinoptera (sp) Cownose ray 67 teeth Westgate

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth Parmley

Sphyrna (sp) Hammerhead Rare Pickering

Squatina (sp) Angel shark 1 tooth Westgate

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth Parmley

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth Parmley

This list does not include other vertebrates

Genus &/or Species Common name Frequency Reporting

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 492 teeth Westgate

Abdounia enniskilleni Extinct Gray Shark 589 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias acutissima Sand Tiger Shark 446 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias cuspidate Great White Shark Abundant Pickering*

Carcharias hopei Sand Tiger Shark 296 Teeth Parmley

Carcharias hopei Sand Tiger shark 922 teeth Westgate

Carcharias koerti Sand Tiger Shark 123 teeth Parmley

Carcharocles angustidens Megatooth Shark 2 Teeth Parmley

Carcharodon auriculatus Giant toothed shark 2 teeth Westgate

Dasyatis (sp) Stingray 53 teeth Westgate

Edaphodon (sp) 1st SE Chimaera Extremely Rare Parmley

Galeo latidens Tiger shark 219 teeth Westgate

Galeocerdo alabamensis Requiem Shark 351 Teeth Parmley

Galecerdo latidens Tiger Shark Abundant Pickering*

Ginglymostoma serra Nurse shark 13 teeth Westgate

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth shark 170 teeth Westgate

Hemipristis curvatus Snaggletooth Shark 635 Teeth Parmley

Heterodontus (sp) Angel Shark 1 Tooth Parmley

Isurus (sp) Mako shark 4 teeth Westgate

Isurus praecursor Mako Shark 27 Teeth Parmley

Lamna (sp) Porbeagle shark 124 teeth Westgate

Lamna Appendiculate Mackerel shark Common Pickering*

Mustelus vanderhoefti Smoothhound Shark 3 Teeth Parmley

Myliobatis (sp) Eagle Ray Abundant Pickering*

Myliobatis (sp) Eagle ray 8 dental batteries/284 teeth Westgate

Nebrius thielensis Nurse Shark 79 Teeth Parmley

Negaprion eurybathrodon Lemon Shark 2127 Teeth Parmley

Negaprion gibbesi Lemon shark 1538 teeth Westgate

Palaeorhincodon Whale Shark 1 tooth Parmley

Physogaleus (sp) Carchrhinid 19 teeth Westgate

Physogaleus secundus Sharpnosed Shark 70 Teeth Parmley

Pristis (sp) Sawfish Very rare Pickering*

Propristis schweinfurthi Sawfish 238 rostral teeth Westgate

Raja (sp) Skate 4 skutes Westgate

Rhinoptera (sp) Cownose ray 67 teeth Westgate

Scyliorhinus gilberti Catshark 53 Teeth Parmley

Sphyrna (sp) Hammerhead Rare Pickering

Squatina (sp) Angel shark 1 tooth Westgate

Squatina prima Angel Shark 6 Teeth Parmley

Striatolamia macrota Sand Shark 1 Tooth Parmley

Clearly, Twiggs Clay, Tivola Limestone and Clinchfield Formation represent three distinct environments requiring high sea levels.

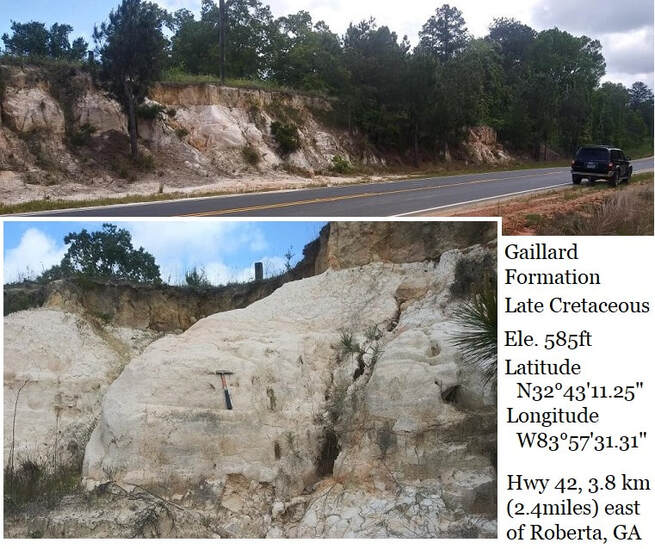

Beneath the Clinchfield Sand at Rich Hill? Huddlestun reports the Gaillard Formation’s kaolin which is at least 68 million years old.

So What About the Sharks, the Fish Teeth?

Excellent question.

Shark teeth are notoriously difficult to identify.

Excellent question.

Shark teeth are notoriously difficult to identify.

Human adults have 32 teeth which break down into 4 types; incisors, canines, premolars & molars. Each tooth is distinct and has evolved into a certain position in your mouth. We grow one set as children and a second set as adults.

Sharks have 50+ teeth depending on the species, and they are constantly losing old teeth and growing new ones. However, each tooth still occupies a certain position in the mouth and is slightly different than the teeth around it. This makes ID difficult even today.

The fact that Veatch & Stephenson did not report occurring fish species in Eocene sediments strongly suggests that they simply lacked such information. Reading the 1911 report you notice that at every list of species they report credits whoever identified the specimens.

Elsewhere in the 1911 reports Veatch and Stephenson record Cretaceous deposits from West Georgia and the published lists of identified shark species. This shows that they were often relying on the work of local researchers. Different researchers have different specialties, interests, and on-hand research materials. So clearly, Veatch & Stephenson lacked identification information on the fish teeth they reported at Rich Hill.

Today such reference material is available, it’s time a fossil record was created for Rich Hill.

Today such reference material is available, it’s time a fossil record was created for Rich Hill.

1991 Section Drawing

In 1991 Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick led a Georgia Geological Society field trip into the Fort Valley plateau and Fall Line Hills area. The researchers explained that their objective was to define and introduce these largely unnamed Middle Eocene, Paleocene & Cretaceous deposits of kaolinitic sands to the geologic public.

Notice that the younger, long named, fossil bearing sediments which had drawn so much interests were of Eocene age, significantly younger than the sediments Huddlestun & Hetrick were focusing on in this study. However, they still produced the best info available on those deposits.

In 1991 Paul Huddlestun and John Hetrick led a Georgia Geological Society field trip into the Fort Valley plateau and Fall Line Hills area. The researchers explained that their objective was to define and introduce these largely unnamed Middle Eocene, Paleocene & Cretaceous deposits of kaolinitic sands to the geologic public.

Notice that the younger, long named, fossil bearing sediments which had drawn so much interests were of Eocene age, significantly younger than the sediments Huddlestun & Hetrick were focusing on in this study. However, they still produced the best info available on those deposits.

They divided the older, newly named deposits into two groups. (6)

- The Oconee Group is of fluvial (river-related) deposits.

- The Oconee Group:

- The Pio Nono Formation (Late Cretaceous)

- The Gaillard Formation (Late Cretaceous)

- Huber Formation (Early Paleocene, late Middle Eocene)

- Fort Valley Group is coastal marine; sea shore.

- Nakomis Formation (Late Cretaceous)

- Marshallville Formation (Early Paleocene)

- Mossy Creek Sand (Middle Eocene, late Claibornian age)

- Perry Sand (Middle Eocene, late Claibornian age)

- The Oconee Group:

They also recognized that they weren't presenting a complete stratigraphic review. “Rather, our purpose is to lay a lithostratigraphic foundation based on the various codes of stratigraphic nomenclature, upon which further geologic studies and stratigraphic refinements may be made.”

Drawing & Description of the Section Exposed at Rich Hill,

Stop 2of the 26th Annual Fieldtrip of the Georgia Geologic Society, Oct 1991

by Huddlestun and Hetrick (6)

Section height; 37.5 meters (123 feet)

Stop 2of the 26th Annual Fieldtrip of the Georgia Geologic Society, Oct 1991

by Huddlestun and Hetrick (6)

Section height; 37.5 meters (123 feet)

Description of the Section Exposed at Rich Hill (6)

Barwell Group, Dry Branch Formation, Irwinton Sand Member

Bed 11; (3 meters/10 feet)

Covered Interval

Twiggs Clay Member

Bed 9; (7 meters/23 feet)

Ocala Group; Tivola Limestone

Bed 8; (6.4 meters/21 feet)

Barnwell Group; Clinchfield Formation

Bed 7; (1.5 meters/5 feet)

Covered interval on west side of ravine; on the east side of the ravine the Clinchfield Sand disconformably overlies…

Oconee Group

Gaillard Formation

Bed 4; (6.4 meters/21 feet)

Barwell Group, Dry Branch Formation, Irwinton Sand Member

Bed 11; (3 meters/10 feet)

- Sand, residuum; argillaceous (clay bearing), fine to medium grained, well sorted, massive, structureless, moderate reddish brown; gradationally overlies…

- Sand and clay; Thinly interbedded, fine-grained, well sorted sand with thin interlayers or laminae of Twiggs-like clay, beds essentially horizontal to subhorizontal; deeply weathered.

Covered Interval

Twiggs Clay Member

Bed 9; (7 meters/23 feet)

- Clay: calcareous toward base, with thin beds or lenses of fine grained limestone scattered throughout, some calcareous concretions in the lower part; clay is sticky and plastic when wet, well bedded to laminated, with blocky to conchoidal fracture; yellowish gray; grades downward through a thin interval (about 1 foot) of thinly bedded, argillaceous limestone into…

Ocala Group; Tivola Limestone

Bed 8; (6.4 meters/21 feet)

- Limestone; abundantly fossiliferous; medium to coarse textured, uneven-grained due to the abundance of clastic (fragmentary) bryozoan debris; very tough and brittle with irregular, bioclastic fracture; some minor quartz sand in the basal (lowest) 1 foot; rudely bedded with scattered thin beds or ledges of more indurated (hardened) limestone, otherwise massive and structureless in appearance. Aequipecten spillmani (scallop) common, rare Periarchus pileussinensis (sand dollar) and molds of mollusks; very pale orange to pale yellowish-orange; grades abruptly downdip into…

Barnwell Group; Clinchfield Formation

Bed 7; (1.5 meters/5 feet)

- Sand: very calcareous, some calcitic shell debris with scattered fragments of Periarchus (sand dollars), less calcareous near base of bed; sand fine to medium grained and well sorted: massive and devoid of sedimentary or biogenic structures except at the top of the bed, the upper 1 foot of Bed 7 consists of a ledge of shaley, granular calcarenite or calcarenitic sand suggesting a discontinuity in deposition; separated from underlying bed by a thin (6 inch) calcareous sandstone ledge:

- Sand: calcareous with a discontinuous ledge or series of calcareous concretions in the middle and basal (base) part of the bed, some calcitic shell fragments, especially in the upper part of the bed; sand fine to medium grained and well sorted; separated from the underlying bed by a calcareous sandstone ledge.

- Sand; noncalcareous, slightly argillaceous; unconsolidated; medium-grained and moderately well sorted; massive and devoid of sedimentary structure.

- On the east side of the ravine, the sand that occurs in this stratigraphic position is that of typical weathered, poorly sorted sand of the Riggins Mill Member.

Covered interval on west side of ravine; on the east side of the ravine the Clinchfield Sand disconformably overlies…

Oconee Group

Gaillard Formation

Bed 4; (6.4 meters/21 feet)

- Kaolin: silty to finely sandy, micaceous, some dark minerals, massive and structureless, blocky fracture, grades downward into…

- Sand; slightly kaolinitic and micaceous; rudely and horizontally stratified; poorly sorted; abruptly overlies…

- Sand; kaolinitic, pebbly; very poorly sorted, generally trough cross bedded; abruptly overlies…

- Sand; kaolinitic, somewhat micaceous, some scattered, thin kaolin lenses; sand medium to medium/coarse grained; moderately to moderately poorly sorted; horizontal to lenticular to planar cross bedded on small scale.

Does a Rich Hill quarry exist?

In 1947 Harry E. LeGrand, a hydrogeologist with the Georgia Geologic Survey, published excellent research on the ground water resources of the Macon area and reported that the Tivola Limestone of Rich Hill had been quarried. (11) In 1990 John Hetrick also mentions “an abandoned quarry at Rich Hill…” (13) But in a 23/April/2021 phone conversation Paul Huddlestun said no such quarry existed to his knowledge and all the outcrops were natural.

In 1947 Harry E. LeGrand, a hydrogeologist with the Georgia Geologic Survey, published excellent research on the ground water resources of the Macon area and reported that the Tivola Limestone of Rich Hill had been quarried. (11) In 1990 John Hetrick also mentions “an abandoned quarry at Rich Hill…” (13) But in a 23/April/2021 phone conversation Paul Huddlestun said no such quarry existed to his knowledge and all the outcrops were natural.

Preservation.

So, would it be worthwhile to preserve Rich Hill for its scientific and educational value? Yes, but only if it is properly protected yet available to researchers with permission fr0m landowners.

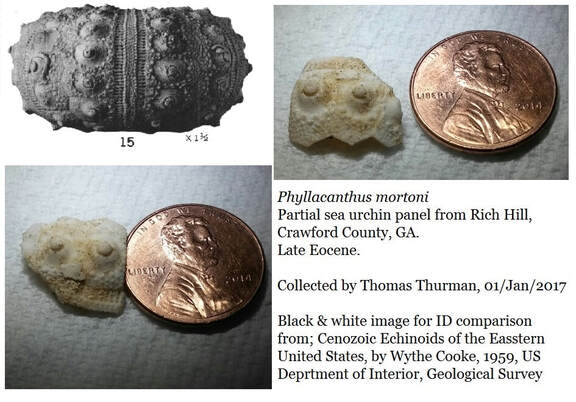

It offers valuable lessons in our ever changing Earth and clearly shows our restless coast lines. There are 34+ million year old sand dollar and sea urchin fossils 177 miles inland and 700+feet above modern sea levels.

Yes, it certainly has scientific, historic, and educational value. Specifically in primary, secondary and advanced educational value, few places in Georgia have a more curious record of climate change. Should field research reveal vertebrate species or tektites this value would increase and nearly demand protection. The site has little commercial value for mining as the deposits are too modest. However, it dramatically shows repeated sea level change and offers a unique glimpse into Georgia’s natural history.

But Rich Hill isn't the only such place in Georgia.

So, would it be worthwhile to preserve Rich Hill for its scientific and educational value? Yes, but only if it is properly protected yet available to researchers with permission fr0m landowners.

It offers valuable lessons in our ever changing Earth and clearly shows our restless coast lines. There are 34+ million year old sand dollar and sea urchin fossils 177 miles inland and 700+feet above modern sea levels.

Yes, it certainly has scientific, historic, and educational value. Specifically in primary, secondary and advanced educational value, few places in Georgia have a more curious record of climate change. Should field research reveal vertebrate species or tektites this value would increase and nearly demand protection. The site has little commercial value for mining as the deposits are too modest. However, it dramatically shows repeated sea level change and offers a unique glimpse into Georgia’s natural history.

But Rich Hill isn't the only such place in Georgia.

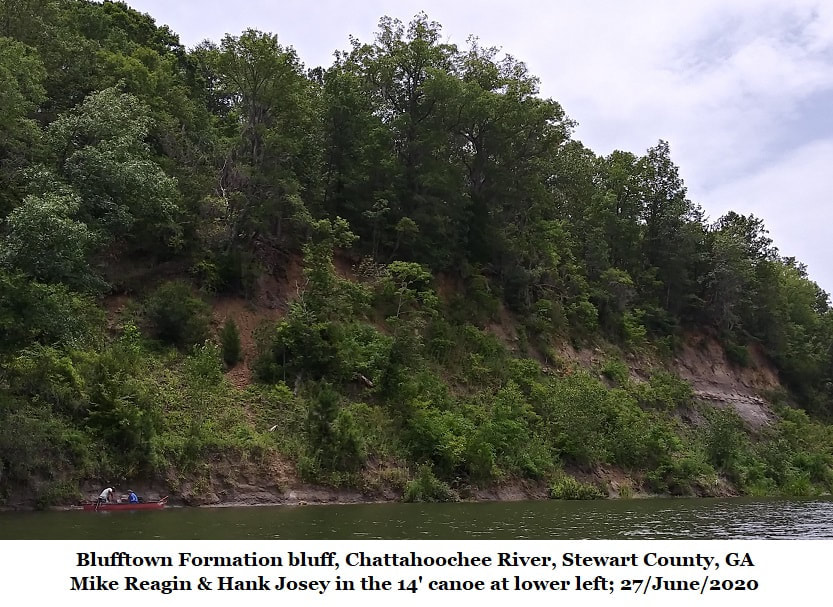

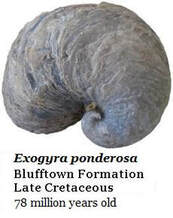

There was once a town in west Georgia, along the Chattahoochee River, known as Blufftown. It stood atop a high, riverside bluff. Even today the lower 25 feet of that bluff is a massive bed of the 77 million year old, spiral, Exogyra ponderosa oysters. (See Section 7I of this website for details.)

There's Shell Bluff, rising 150 feet above the Savannah River in East Georgia. It's formed primarily by another bed of uncounted 34 million year old oysters, Crassostrea gigantissama, a giant oyster which reportedly reached 22" in length, and 18" individuals are common. This is the same species Sam Pickering reported from the Clinchfield Formation. The history of ShellBluff goes back to Hernando de Soto's visiting the site in 1540. Then William Bartram, the father of American botany, visited in 1765 and first described the large fossil oysters found there.

(See Section 14K of this website for more details.)

This rich natural history of Georgia is only useful for education if it is accessible to teachers, parents, & students. Currently, such valuable histories are rarely taught in our schools. Many parents object to schools teaching the science that shows a truly ancient Georgia, a truly ancient Earth.

There are 513 million year old fossils in northwest Georgia. (See Section 1 of this website.)

So should state or federal money be spent preserving Georgia's most famous fossil localities? Yes, it should. Eventually Georgia parents will demand that schools teach the science which shows an ever changing, ancient Earth. How can we prepare our children for a warming global climate if we don't show them that this has happened before?

There's Shell Bluff, rising 150 feet above the Savannah River in East Georgia. It's formed primarily by another bed of uncounted 34 million year old oysters, Crassostrea gigantissama, a giant oyster which reportedly reached 22" in length, and 18" individuals are common. This is the same species Sam Pickering reported from the Clinchfield Formation. The history of ShellBluff goes back to Hernando de Soto's visiting the site in 1540. Then William Bartram, the father of American botany, visited in 1765 and first described the large fossil oysters found there.

(See Section 14K of this website for more details.)

This rich natural history of Georgia is only useful for education if it is accessible to teachers, parents, & students. Currently, such valuable histories are rarely taught in our schools. Many parents object to schools teaching the science that shows a truly ancient Georgia, a truly ancient Earth.

There are 513 million year old fossils in northwest Georgia. (See Section 1 of this website.)

So should state or federal money be spent preserving Georgia's most famous fossil localities? Yes, it should. Eventually Georgia parents will demand that schools teach the science which shows an ever changing, ancient Earth. How can we prepare our children for a warming global climate if we don't show them that this has happened before?

References

- Veatch, Otto; Stephenson, Lloyd, William; Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 26, 1911

- Cooke, C. Wythe; Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; United States Department of Interior (Now the USGS), Bulletin 941, 1943

- Cooke; Wythe Charles, Shearer; Harold Kurtz; Deposits of Clairborne and Jackson Age, USGS Professional Paper 120-C, 1919

- Thurman,Thomas; 14B; Fossils, Impacts & Tektites Dating the Clinchfield Formation - Exploring Georgia's Fossil Record & Our History of Paleontology; GeorgiasFossils.com

- Pickering, Sam M. Jr.; Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangle, Georgia; Bulletin 81, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1970

- Huddlestun, Paul F & Hetrick, John H.; Stratigraphic Framework of the Fort Valley Plateau and Central Kaolin District, 26th Annual Fieldtrip of the Georgia Geologic Society, Georgia Geological Society Guidebooks, Volume 11, No.1, October 1991

- Rainwater E.H.; LaMoreaux, Philip E.; Herrick, S.M. PhD., MacNeil; F. Stearns; Furcron, A. S. PhD.; Southeastern Geological Society, Second Field Trip; November 1944.

- Thurman,Thomas; Section 12C; Cynthiacetus; GeorgisFossils.com

- Huddlestun, Paul F.; Hetrick, John H.; Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central & Eastern Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 95, 1986.

- Paleo-Data; PDI Paleogene Biostratigraphic Chart – Gulf Basin, USA. Updated March 2o17; https://www.paleodata.com/chart/

- LeGrand, H.E.; Geology and Ground-Water Resources of the Macon Area, Georgia; Prepared by the United States Geological Survey in Cooperation with the Georgia Geological Survey, 1962

- Russell, Dale A.; Rich, Frederick J.; Schneider, Vincent; Lynch-Stieglits, Jean; A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.