18: Miocene Epoch;

23.3 to 5.3 million years ago

The Miocene knew frequent and often dramatic climate change.

By the Miocene most of the world’s animals would have been recognizable to us as related to modern species.

Miocene sediments are common in south, east and southeastern Georgia; right to the coastline where sediments from different geologic periods can be stacked like many thin pancakes and often mixed with more recent sediments.

The Miocene aged Altamaha Formation of Southeast Georgia is one of the most widespread surface formations in the state; unfortunately it is an erosional feature and bears few if any fossils. It has produced most of Georgia’s Tektites (georgiaites) as secondary deposits from erosion.

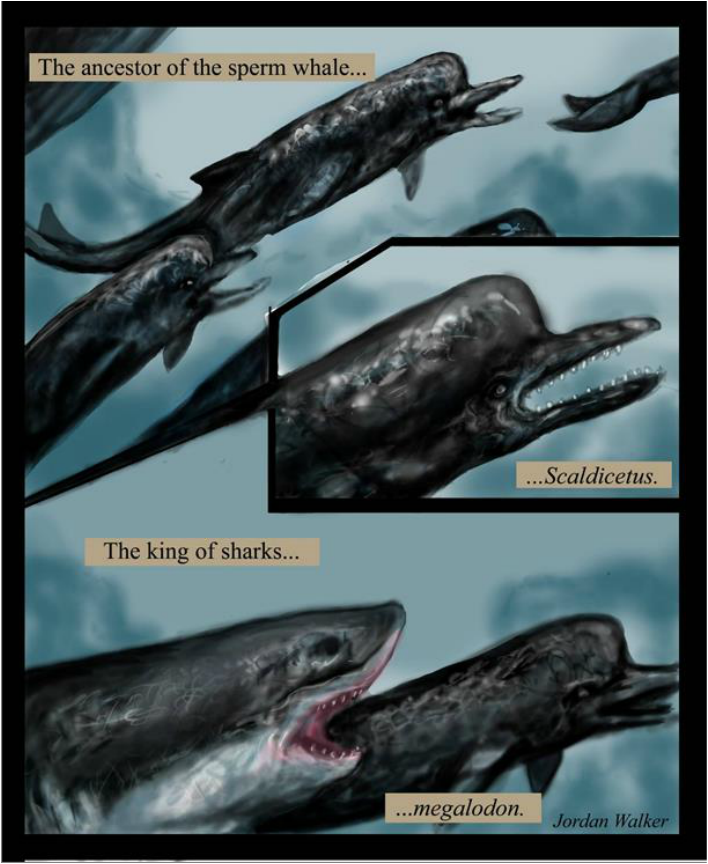

Shark vs. Whale

A megalodon shark fossil was reported from field research a few miles northwest of Savannah in 1998 by paleontologists Dr. Richard Hulbert and Dr. Anne Pratt; nothing very unusual there, they recovered both a megalodon tooth and single Scaldicetus whale fossil from the same sediment bed. Both of these species are well know from Coastal Georgia. It is impossible to know if these two share a history.

A megalodon shark fossil was reported from field research a few miles northwest of Savannah in 1998 by paleontologists Dr. Richard Hulbert and Dr. Anne Pratt; nothing very unusual there, they recovered both a megalodon tooth and single Scaldicetus whale fossil from the same sediment bed. Both of these species are well know from Coastal Georgia. It is impossible to know if these two share a history.

The images of Scaldicetus and megalodon were created by Jordan Walker.

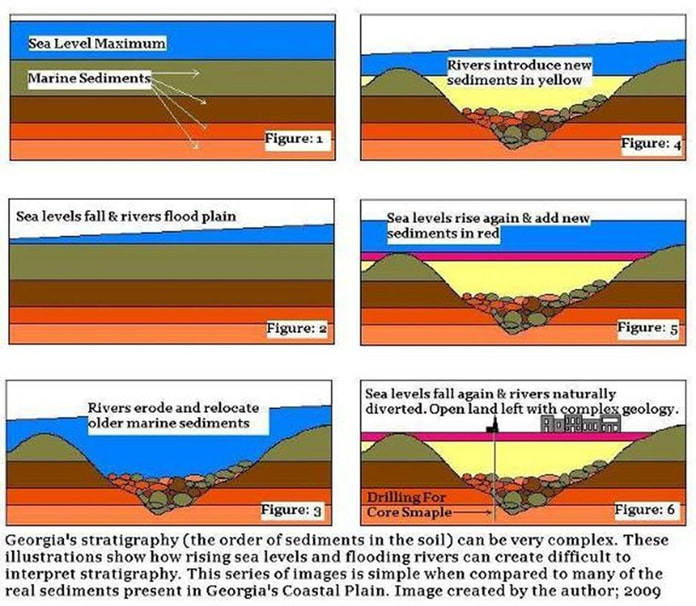

Repeated cycles of erosion, transportation by water, deposition, erosion, repeat transportation and renewed deposition can make sediments very near the coastline difficult to interpret. In many cases, you can find fossils from wide spans of time jumbled together as rising and falling sea levels and rivers have relocated fossils repeatedly.

The Miocene is seen as generally cool when compared to earlier times; this is particularly true for the late Miocene which saw the start of the repetitive ice ages which continue today.

The Miocene is seen as generally cool when compared to earlier times; this is particularly true for the late Miocene which saw the start of the repetitive ice ages which continue today.

Scaldicetus; the Killer Sperm Whale

Scaldicetus is a genus of Miocene toothed whale and a member of the sperm whale family. It is often referred to as a killer sperm whale. The genus has been described as a train-wreck as it was founded on a single tooth. Still, in recent years the killer sperm whale family has grown, though many species in it have been reassigned away from Scaldicetus and new genres of closely related whales have been erected to house the killer sperm whale clan. For all of that Scaldicetus remains a valid genre. Whether the material collected by Hulbert & Pratt will be re-assigned is yet to be seen.

In 2006 Giovanni Bianucci & Walter Landini described a nearly complete Late Miocene whale fossil from Italy in a paper entitled: Killer sperm whale: a new physeteroid (Mamalia, Cetacea) from the Late Miocene of Italy. “Physeteroid” is the scientific term for the superfamily of sperm whales which include three modern members; the sperm whale, the pygmy sperm whale and the dwarf sperm whale.

Bianucci and Landini go on to describe a whale which would have measured about 7 meters (22.9 ft) in life. Originally it was assigned to the genus Scaldicetus, given the species name degiorgii and compared favorably to the previously described Japanese fossil Scaldicetus shigensis.

Since then, Scaldicetus shigensis has been reassigned as Brygmophyseter shigensis. The Italian fossil Scaldicetus degigorgii has been reassigned as Zygorphyseter varolai. The Hulbert & Pratt’s Georgia specimen quietly sits on its Scalicetus identity.

The Italian specimen, Zygorphyseter varolai, was probably closely related to our Georgia find. This 7 meter (23ft) animal is seen as an active predator capable of taking large prey, probably as capable a hunter as the modern killer whale.

Z. varolai had a very distinctive skull; it was deeply recessed like a modern toothed whale, a sure sign that this was a whale which possessed a significant spermaceti organ or melon capable of echolocation. It also possessed a beak like a modern bottle nosed dolphin. Its jaws, while beaked towards the front were wide towards the rear and hinged in such a way that the animal would have been able to open its mouth widely, at least by the standards of modern whales. In reconstruction it is seen that Z. varolai would have had a prominent melon and a beak, with stout, inward curved peg teeth, deeply rooted.

Research in the last decade indicates that whales (the cetaceans in general) seemed to have achieved their greatest diversity during the Miocene Epoch.

The typical Scaldicetus whale fossil is a somewhat fat, banana-shaped tooth several inches long. Scaldicetus is known from the North American east and west coast as well as Europe and Japan. Specimens of Scaldicetus teeth from the Southeastern USA can usually be found online for purchase.

As we’ve seen Megalodon teeth are also well known from Georgia and there are usually high quality, large Georgia specimens available for sale on the internet.

The evidence suggest that Scaldicetus was a capable animal well equipped with echolocation but in the following images by Jordan Walker asks the question; how well could it have protected itself from C. megalodon? C. megalodon lingered until the Pleistocene when it was finally outcompeted by newly emerged whales capable of hunting in polar and tropical seas.

Even Scaldicetus, a warm water whale, would have been vulnerable from an attack from below or behind, especially from a fast predator more than twice its size and mass.

Life on Land

During the Miocene grasses expanded their range and diversified dramatically as the warmer climate forests receded. Herbivore grazers, eating grasses, also expanded their ranges and diversified.

This closely impacted the evolution of horses.

Horses emerge during the Middle Eocene with the genus Hyracotherium, the dawn horse. At less than 24 inches long the small dawn horse lived in the forests and is known from North America, Asia and Europe.

Weighing something less than 40 pounds it was a browser eating leaves off trees and shrubbery. It stood on four front toes and three rear toes, each toe possessed a pad on the bottom, much like a modern dog’s. As grasses emerged and became widespread some members of the horse family shifted to that as a food source. They became grazers and expanded dramatically.

Grass is an abrasive food, so any mutations toward stronger teeth offered a distinct advantage and the fossil record shows an evolutionary progression of increasingly larger and more durable teeth.

Grass covered prairies and steppes also offer little cover, so any mutation which increased an animal’s speed and endurance also offered a distinct advantage towards evading predators and would be reproduced and magnified in its offspring.

Herding too is an excellent defense against predators where there is no cover.

Over time, the horses became longer limbed and more specialized towards running, one of these adaptations was the loss of toes in contact with the ground. Modern horses stand, walk and run on only one toe per foot, unlike the vast majority of hoofed animals, horses only have one hoof per leg. This is an evolutionary specialization towards speed and endurance.

Miocene Epoch

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; Downloaded 7/April/2013 Online Collections Catalog; Georgia Specimens

Genus & Species Common Name Specimens Location

Reptile

Order: Crocodilia Crocodile Skull Element None Listed

Fish

Aetobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Dermal bone None Listed

Carcharhinus egertoni Requiem Shark Tooth None Listed

Carcharodon carcharias Great White Tooth None Listed

Carcharodon megalodon Megalodon 2 Teeth Coffee County

Carcharodon megalodon Megelodon 4 Teeth None Listed

Galeocerdo aduncus Requiem Shark 2 Teeth None Listed

Galeocerdo contortus Requiem Shark Tooth None Listed

Hemipristis serra Weasel Shark 3 Teeth None Listed

Isurus desori Mackerel Shark Tooth None Listed

Isurus hastalis Mackerel Shark Tooth Chatham Cnty 1927

Isurus hastalis Mackerel Shark 4 Teeth None Listed

Negaprion (species?) Lemon Shark 5 Teeth None Listed

Odontaspis cuspidate Sand Tiger 21 Teeth None Listed

Raja (species?) Skate Dermal Bone None Listed

Sphyrna prisca Hammerhead 2 Teeth None Listed

Mammal

Delphinodon (species?) Early Porpoise Skull None Listed

Mesoplodon (species?) Beaked Whale Ear Bone None Listed

Metaxytherium (species?) Dugong Incisor Chatham County

Ontocetus emmonsi Walrus Partial Tooth None Listed 1934

Scaldicetus (species?) Killer Sperm Whale 2 Teeth None Listed

Scaldicetus is a genus of Miocene toothed whale and a member of the sperm whale family. It is often referred to as a killer sperm whale. The genus has been described as a train-wreck as it was founded on a single tooth. Still, in recent years the killer sperm whale family has grown, though many species in it have been reassigned away from Scaldicetus and new genres of closely related whales have been erected to house the killer sperm whale clan. For all of that Scaldicetus remains a valid genre. Whether the material collected by Hulbert & Pratt will be re-assigned is yet to be seen.

In 2006 Giovanni Bianucci & Walter Landini described a nearly complete Late Miocene whale fossil from Italy in a paper entitled: Killer sperm whale: a new physeteroid (Mamalia, Cetacea) from the Late Miocene of Italy. “Physeteroid” is the scientific term for the superfamily of sperm whales which include three modern members; the sperm whale, the pygmy sperm whale and the dwarf sperm whale.

Bianucci and Landini go on to describe a whale which would have measured about 7 meters (22.9 ft) in life. Originally it was assigned to the genus Scaldicetus, given the species name degiorgii and compared favorably to the previously described Japanese fossil Scaldicetus shigensis.

Since then, Scaldicetus shigensis has been reassigned as Brygmophyseter shigensis. The Italian fossil Scaldicetus degigorgii has been reassigned as Zygorphyseter varolai. The Hulbert & Pratt’s Georgia specimen quietly sits on its Scalicetus identity.

The Italian specimen, Zygorphyseter varolai, was probably closely related to our Georgia find. This 7 meter (23ft) animal is seen as an active predator capable of taking large prey, probably as capable a hunter as the modern killer whale.

Z. varolai had a very distinctive skull; it was deeply recessed like a modern toothed whale, a sure sign that this was a whale which possessed a significant spermaceti organ or melon capable of echolocation. It also possessed a beak like a modern bottle nosed dolphin. Its jaws, while beaked towards the front were wide towards the rear and hinged in such a way that the animal would have been able to open its mouth widely, at least by the standards of modern whales. In reconstruction it is seen that Z. varolai would have had a prominent melon and a beak, with stout, inward curved peg teeth, deeply rooted.

Research in the last decade indicates that whales (the cetaceans in general) seemed to have achieved their greatest diversity during the Miocene Epoch.

The typical Scaldicetus whale fossil is a somewhat fat, banana-shaped tooth several inches long. Scaldicetus is known from the North American east and west coast as well as Europe and Japan. Specimens of Scaldicetus teeth from the Southeastern USA can usually be found online for purchase.

As we’ve seen Megalodon teeth are also well known from Georgia and there are usually high quality, large Georgia specimens available for sale on the internet.

The evidence suggest that Scaldicetus was a capable animal well equipped with echolocation but in the following images by Jordan Walker asks the question; how well could it have protected itself from C. megalodon? C. megalodon lingered until the Pleistocene when it was finally outcompeted by newly emerged whales capable of hunting in polar and tropical seas.

Even Scaldicetus, a warm water whale, would have been vulnerable from an attack from below or behind, especially from a fast predator more than twice its size and mass.

Life on Land

During the Miocene grasses expanded their range and diversified dramatically as the warmer climate forests receded. Herbivore grazers, eating grasses, also expanded their ranges and diversified.

This closely impacted the evolution of horses.

Horses emerge during the Middle Eocene with the genus Hyracotherium, the dawn horse. At less than 24 inches long the small dawn horse lived in the forests and is known from North America, Asia and Europe.

Weighing something less than 40 pounds it was a browser eating leaves off trees and shrubbery. It stood on four front toes and three rear toes, each toe possessed a pad on the bottom, much like a modern dog’s. As grasses emerged and became widespread some members of the horse family shifted to that as a food source. They became grazers and expanded dramatically.

Grass is an abrasive food, so any mutations toward stronger teeth offered a distinct advantage and the fossil record shows an evolutionary progression of increasingly larger and more durable teeth.

Grass covered prairies and steppes also offer little cover, so any mutation which increased an animal’s speed and endurance also offered a distinct advantage towards evading predators and would be reproduced and magnified in its offspring.

Herding too is an excellent defense against predators where there is no cover.

Over time, the horses became longer limbed and more specialized towards running, one of these adaptations was the loss of toes in contact with the ground. Modern horses stand, walk and run on only one toe per foot, unlike the vast majority of hoofed animals, horses only have one hoof per leg. This is an evolutionary specialization towards speed and endurance.

Miocene Epoch

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; Downloaded 7/April/2013 Online Collections Catalog; Georgia Specimens

Genus & Species Common Name Specimens Location

Reptile

Order: Crocodilia Crocodile Skull Element None Listed

Fish

Aetobatis (species?) Eagle Ray Dermal bone None Listed

Carcharhinus egertoni Requiem Shark Tooth None Listed

Carcharodon carcharias Great White Tooth None Listed

Carcharodon megalodon Megalodon 2 Teeth Coffee County

Carcharodon megalodon Megelodon 4 Teeth None Listed

Galeocerdo aduncus Requiem Shark 2 Teeth None Listed

Galeocerdo contortus Requiem Shark Tooth None Listed

Hemipristis serra Weasel Shark 3 Teeth None Listed

Isurus desori Mackerel Shark Tooth None Listed

Isurus hastalis Mackerel Shark Tooth Chatham Cnty 1927

Isurus hastalis Mackerel Shark 4 Teeth None Listed

Negaprion (species?) Lemon Shark 5 Teeth None Listed

Odontaspis cuspidate Sand Tiger 21 Teeth None Listed

Raja (species?) Skate Dermal Bone None Listed

Sphyrna prisca Hammerhead 2 Teeth None Listed

Mammal

Delphinodon (species?) Early Porpoise Skull None Listed

Mesoplodon (species?) Beaked Whale Ear Bone None Listed

Metaxytherium (species?) Dugong Incisor Chatham County

Ontocetus emmonsi Walrus Partial Tooth None Listed 1934

Scaldicetus (species?) Killer Sperm Whale 2 Teeth None Listed