14; Taylors Bluff

Paleo Paddling the Ocmulgee River

28/July/2019

By Thomas Thurman

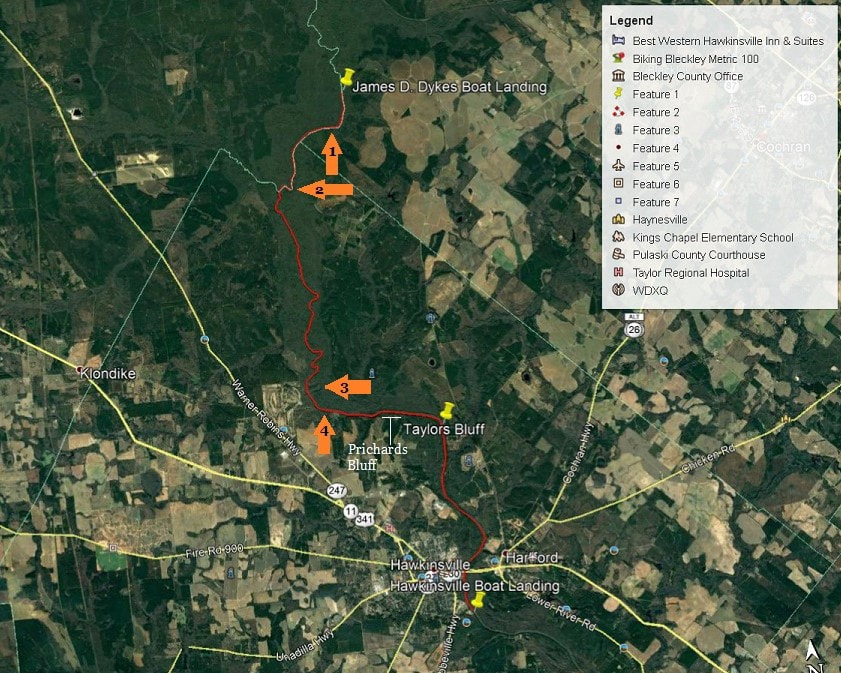

On 27/July/2019 Hank Josey, Michael Hallen, Gloria Hallen, Samantha Thurman and myself (Thomas Thurman) paddled 14 river miles (22.5 river km) down the Ocmulgee River to perform observations at Taylors Bluff, the type locality of the latest Eocene Ocmulgee Formation.

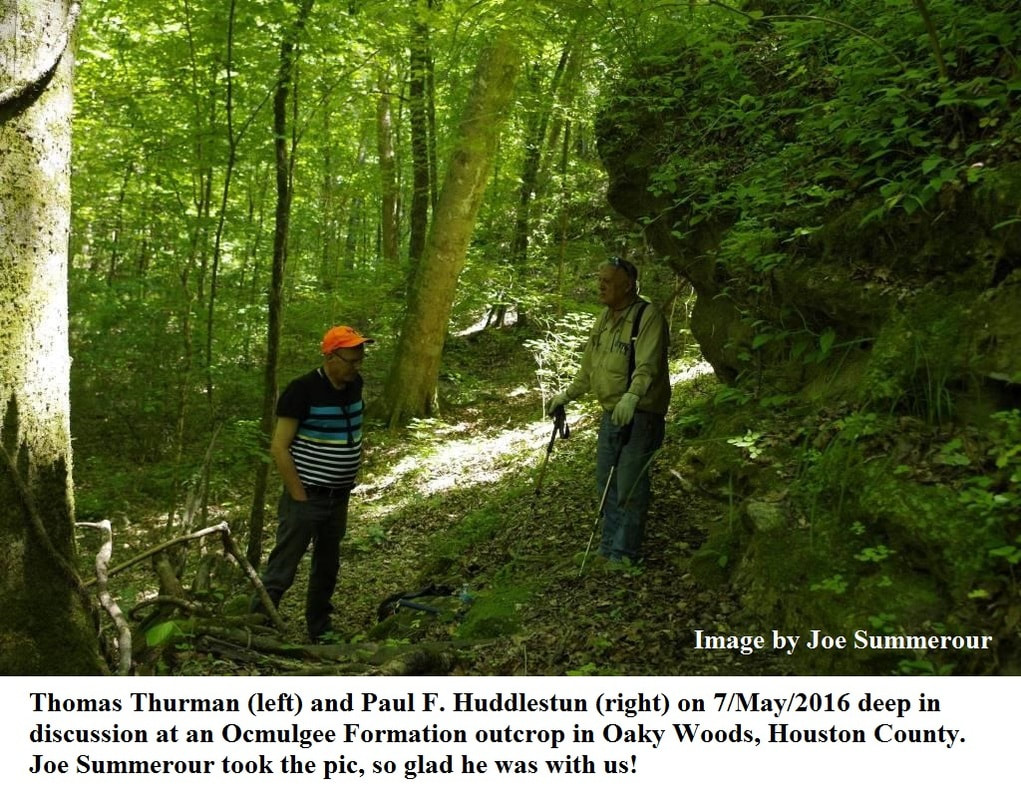

Our goal was to compare observations of the Ocmulgee Formation at the type locality with observations of assumed Ocmulgee Formation outcrops in Oaky Woods Wildlife Management area.

We put into the river at James D Dykes Boat Landing in Bleckley County around 9:00 am and headed south with the current. Both Michael and Gloria were paddling kayaks, Hank was alone in his canoe while my daughter Samantha & I shared our canoe.

Dykes Landing is 5.5 air miles (8.85km) southeast of Oaky Woods. For most of our trip the Ocmulgee Wildlife Management Area would be to our left, eastward.

Dykes Landing is 5.5 air miles (8.85km) southeast of Oaky Woods. For most of our trip the Ocmulgee Wildlife Management Area would be to our left, eastward.

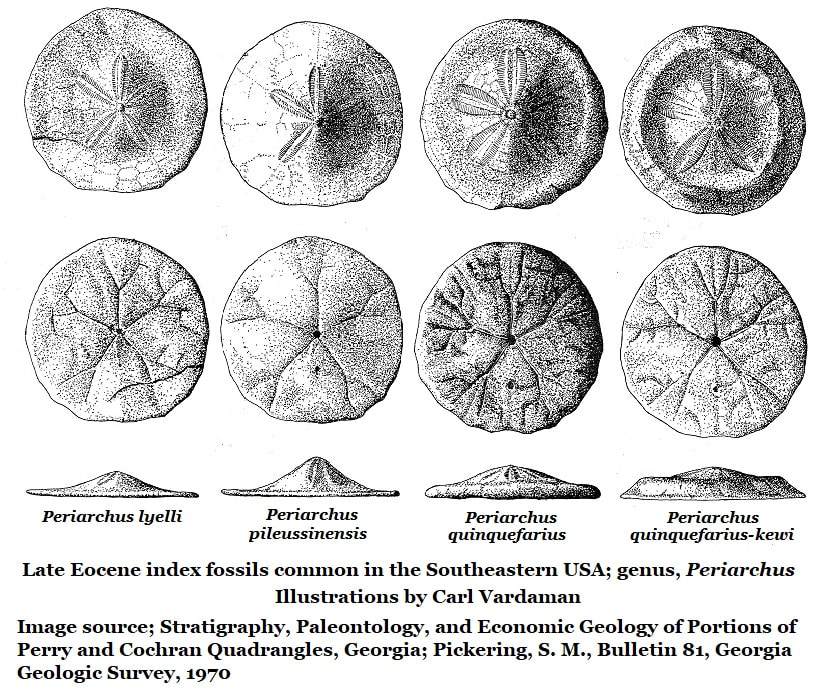

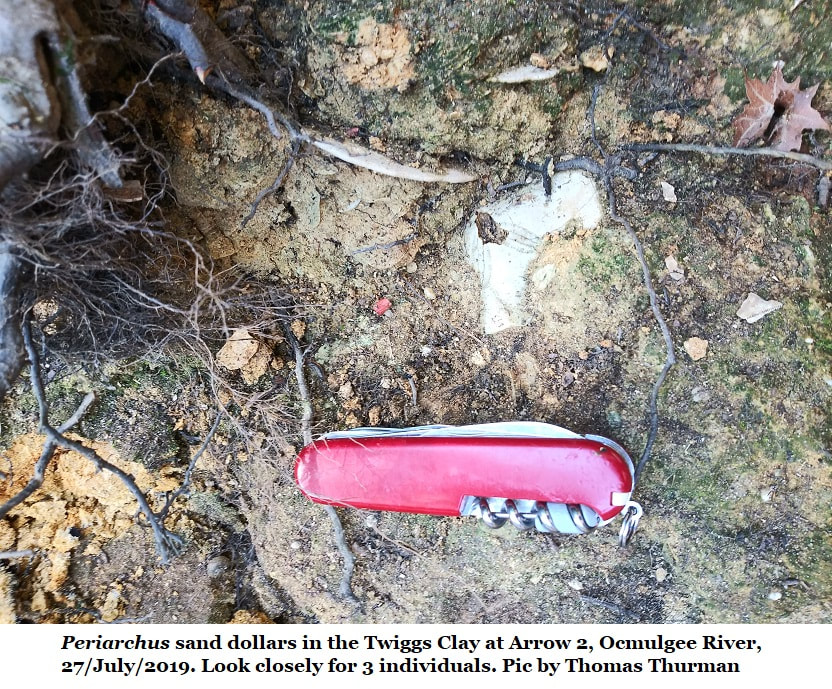

Within minutes Hank and I spotted interesting rocks scattered on the eastern bank, so we beached the canoes and climbed out for a look. (Arrow 1) Fossils were quickly evident and a few Periarchus pileussinensis sand dollars were identified in the soil confirming the sediments as Late Eocene. After some discussion Hank and I decided were we looking at the Twiggs Clay. Google Earth sets the elevation at 230 feet. A few samples were collected, we climbed back into the canoes and continued downstream.

The sand dollar genus Periarchus is an index fossil for Late Eocene, Southeastern USA sediments. The Late Eocene, known as the Priabonian Stage, extends from 37.2 to 33.9 million years ago. During this period the genus Periarchus proliferated in the Southeast. But at the global glacial event which ended the Eocene Epoch and initiated the Oligocene Epoch, 33.9 million years ago, Periarchus went extinct. It has never been reported in any Oligocene sediments.

In 1986 Huddlestun used foraminifera (foram) fossils to show that the Twiggs Clay was Priabonian, Late Eocene or roughly 34.5 million years old. Forams allow very accurate dating of sediments but border on being microscopic, but Periarchus sand dollars give of a good time-mark.

The River

We were soon back on the water, we had a long paddle ahead of us and were concerned about running out of daylight. Our goal was still a good 10 river miles downstream.

A couple of miles downstream we reached the sharpest bend and largest sandbar we’d encounter on our trip. So we took a short break, beached the boats and explored the sandbar. The thick, wet quartz sand was difficult to walk on near the river but higher up it was drier and easier to cross.

We began to find empty white eggs, soft shelled, just smaller than a ping-pong ball scattered in loose groups in the drier sand. All had seemingly recently hatched. They were probably turtle eggs. There were easily a dozen empty eggshells scattered around.

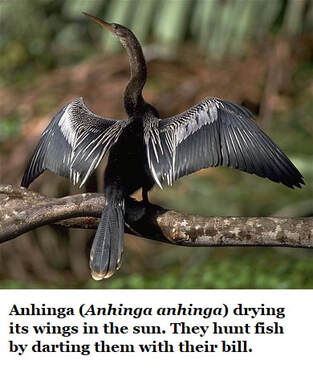

Back on the water the green of Georgia in July was staggering; I was amazed by the number of willow trees and grand old bald cypress trees along the banks. But we were surprised and saddened by how little wildlife we saw. There was one anhinga drying its wings on a fallen tree just as we got started. There were a few herons, far fewer turtles than I expected, no snakes, and we saw no mammals at all. I did glimpse the back of a very large gar swimming past us.

We were thankful for a cool, brightly summer day. It’d been an oppressively hot July and our relatively mild Saturday on the river was a joy, we even had frequent cool breezes. Around noon we put in at an old oxbow along the river to eat a light lunch.

Soon back on the water we were nearing the hard, eastern turn of the river where it met Prichards Bluff.

We were soon back on the water, we had a long paddle ahead of us and were concerned about running out of daylight. Our goal was still a good 10 river miles downstream.

A couple of miles downstream we reached the sharpest bend and largest sandbar we’d encounter on our trip. So we took a short break, beached the boats and explored the sandbar. The thick, wet quartz sand was difficult to walk on near the river but higher up it was drier and easier to cross.

We began to find empty white eggs, soft shelled, just smaller than a ping-pong ball scattered in loose groups in the drier sand. All had seemingly recently hatched. They were probably turtle eggs. There were easily a dozen empty eggshells scattered around.

Back on the water the green of Georgia in July was staggering; I was amazed by the number of willow trees and grand old bald cypress trees along the banks. But we were surprised and saddened by how little wildlife we saw. There was one anhinga drying its wings on a fallen tree just as we got started. There were a few herons, far fewer turtles than I expected, no snakes, and we saw no mammals at all. I did glimpse the back of a very large gar swimming past us.

We were thankful for a cool, brightly summer day. It’d been an oppressively hot July and our relatively mild Saturday on the river was a joy, we even had frequent cool breezes. Around noon we put in at an old oxbow along the river to eat a light lunch.

Soon back on the water we were nearing the hard, eastern turn of the river where it met Prichards Bluff.

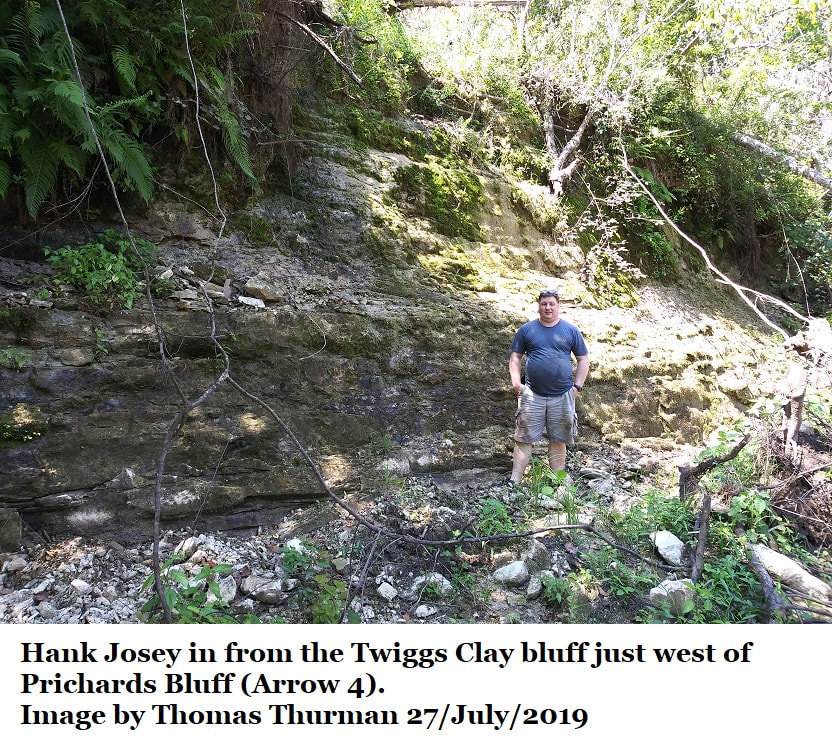

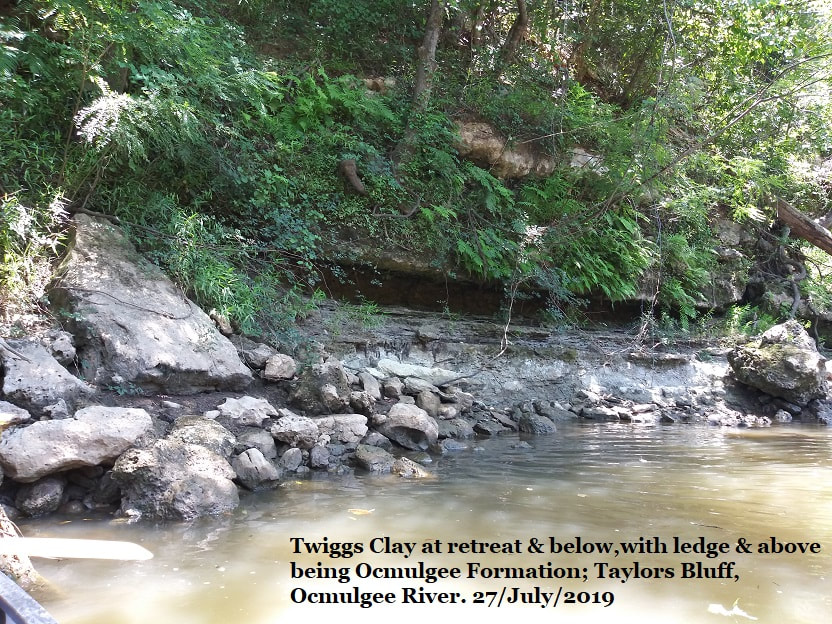

The Twiggs Clay

Just upstream from Prichards Bluff (Arrow 4) we noticed a dark, weathered, stratified cliff roughly 5 meters (16ft) high. We landed the canoes and Hank & I got out for a look. It was Twiggs Clay, so slippery you could hardly walk on the ledge at the base of the cliff. Though we didn’t spend a great deal of time with it, the Twiggs itself at this location seemed to be pure, bedded, dark clay. A cursory inspection seemed to show little obvious variation in the individual beds.

On the riverbank was a fallen tree which had a boulder trapped in its root ball. The boulder was dove-grey and multiple individual Periarchus were observed in the boulder. We identified the boulder as Ocmulgee Formation limestone, which overlies the Twiggs Clay. It’s interesting to note that Google Earth shows an elevation of 234 feet for this location.

Just upstream from Prichards Bluff (Arrow 4) we noticed a dark, weathered, stratified cliff roughly 5 meters (16ft) high. We landed the canoes and Hank & I got out for a look. It was Twiggs Clay, so slippery you could hardly walk on the ledge at the base of the cliff. Though we didn’t spend a great deal of time with it, the Twiggs itself at this location seemed to be pure, bedded, dark clay. A cursory inspection seemed to show little obvious variation in the individual beds.

On the riverbank was a fallen tree which had a boulder trapped in its root ball. The boulder was dove-grey and multiple individual Periarchus were observed in the boulder. We identified the boulder as Ocmulgee Formation limestone, which overlies the Twiggs Clay. It’s interesting to note that Google Earth shows an elevation of 234 feet for this location.

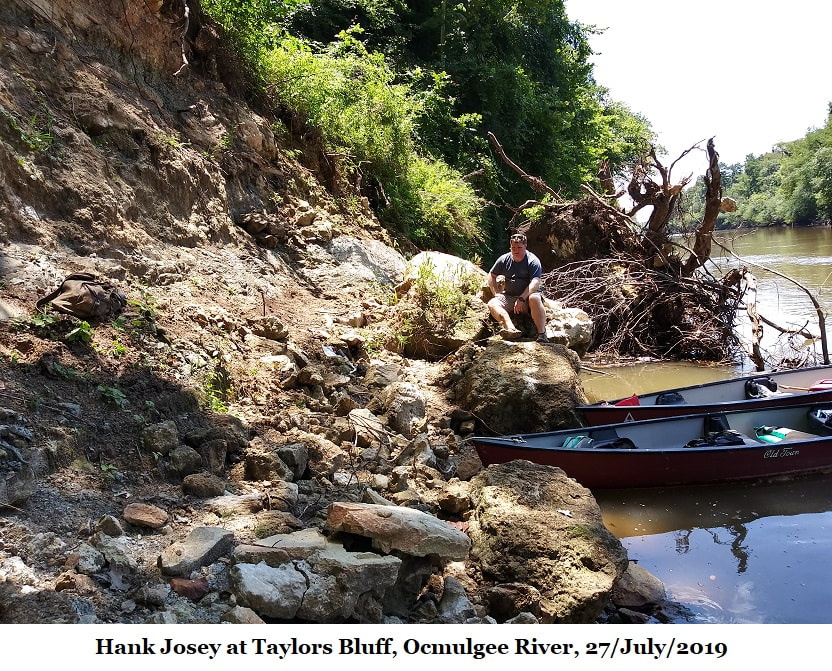

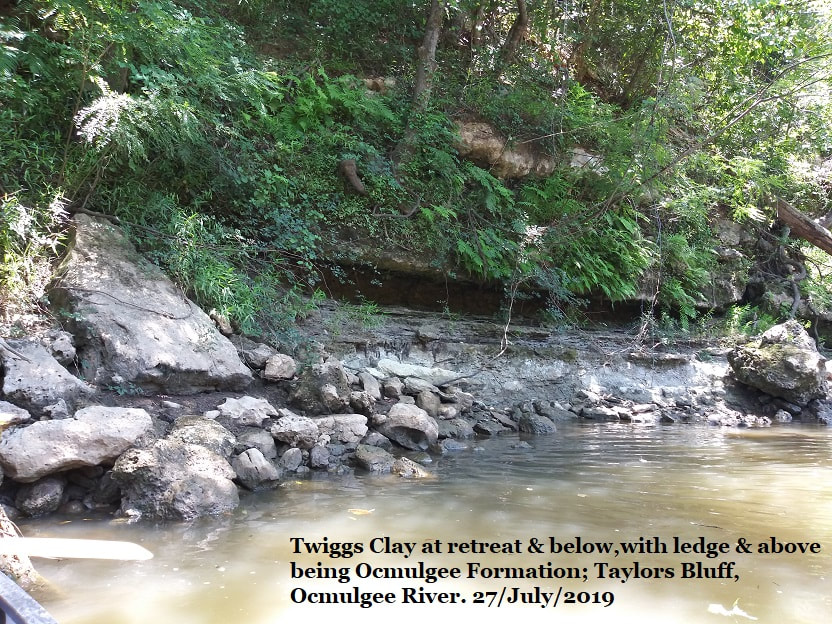

Taylors Bluff

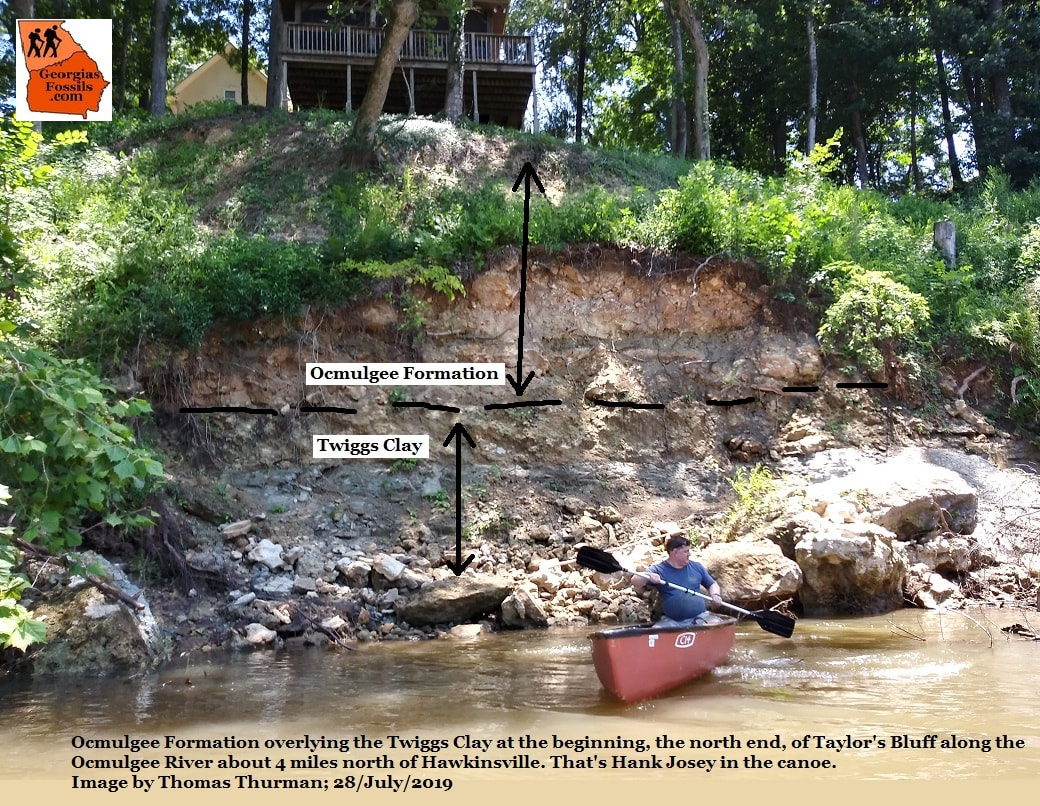

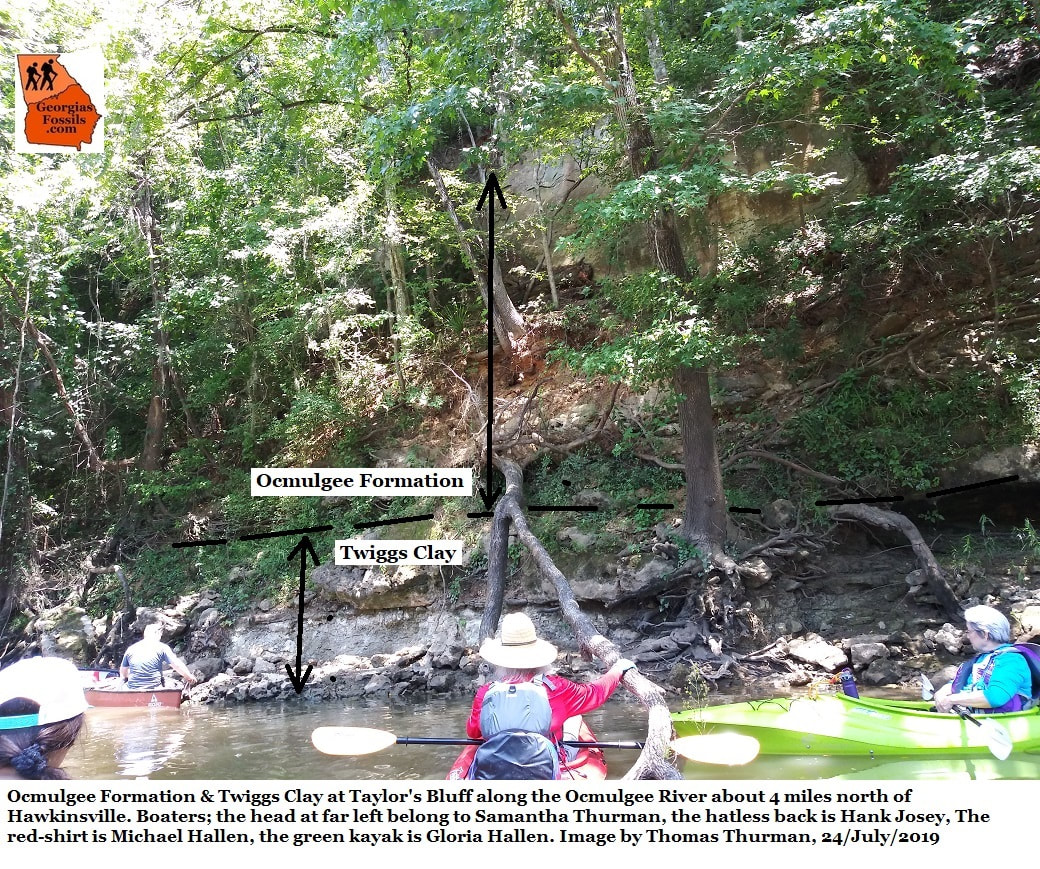

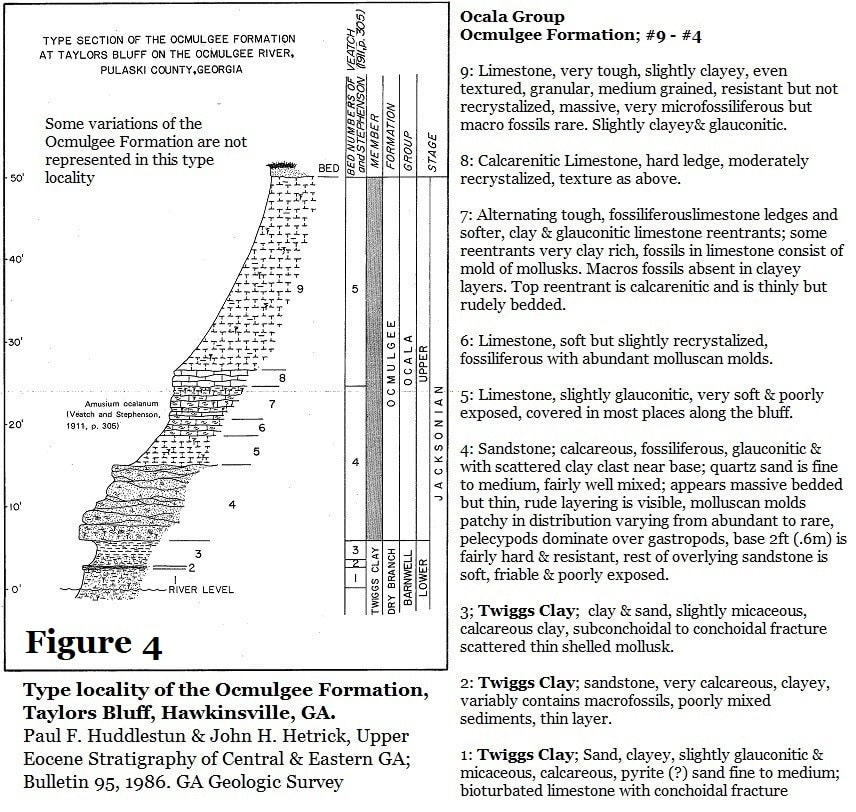

The next stop for our trip was our target; Taylors Bluff, the type locality Paul Huddlestun assigned for the Ocmulgee Formation. The elevation for the base of Taylors Bluff, is 207 feet (Google Earth) and the bluff rises to approximately 260 feet. Taylors Bluff is 11 miles (17.69km) SSE of Oaky Woods. As you can see from the pictures, the bluff reaches a good 50 feet (15 meters) in height.

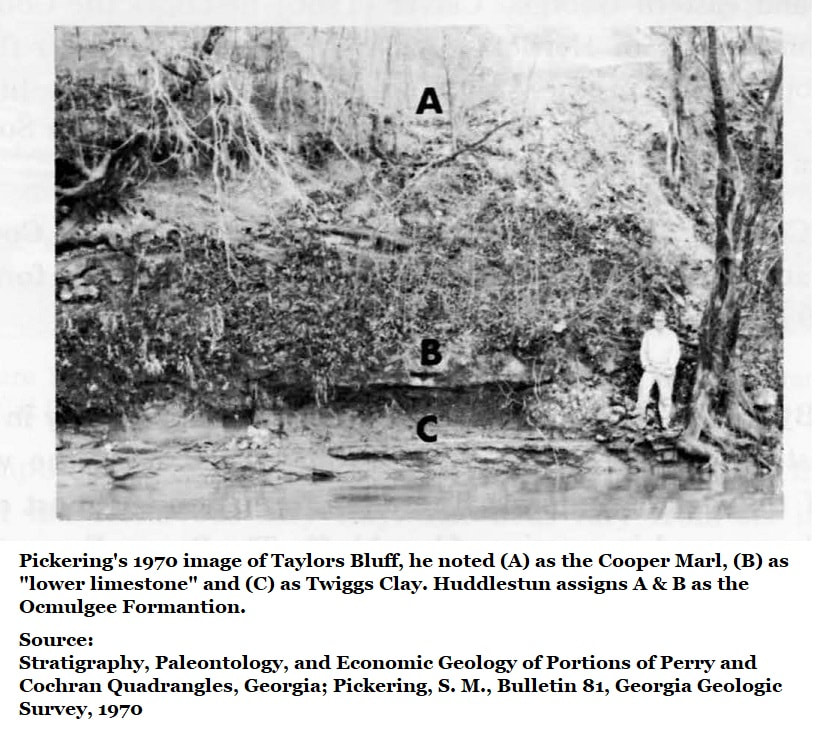

In 1986 Paul Huddlestun reviewed the bluff and created this section drawing. The lowest sections 1 through 3 (7 ft or 2.1 meters) of the bluff he identified as Twiggs Clay. The overlying 43 feet (13.1 meters), sections 4 through 9, he assigned as the Ocmulgee Formation. The variable nature of the Ocmulgee Formation that Huddlestun recorded at Taylors Bluff is noteworthy. There is even greater variability in some of the observed outcrops in Oaky Woods WMA.

The next stop for our trip was our target; Taylors Bluff, the type locality Paul Huddlestun assigned for the Ocmulgee Formation. The elevation for the base of Taylors Bluff, is 207 feet (Google Earth) and the bluff rises to approximately 260 feet. Taylors Bluff is 11 miles (17.69km) SSE of Oaky Woods. As you can see from the pictures, the bluff reaches a good 50 feet (15 meters) in height.

In 1986 Paul Huddlestun reviewed the bluff and created this section drawing. The lowest sections 1 through 3 (7 ft or 2.1 meters) of the bluff he identified as Twiggs Clay. The overlying 43 feet (13.1 meters), sections 4 through 9, he assigned as the Ocmulgee Formation. The variable nature of the Ocmulgee Formation that Huddlestun recorded at Taylors Bluff is noteworthy. There is even greater variability in some of the observed outcrops in Oaky Woods WMA.

The Taylors Bluff observations we performed from the river in July 2019 agree with and confirm Huddlestun’s assessment, but admittedly we were not equipped to scale the bluff. Our observations seemed to confirm that what we’re seeing in Oaky Woods is relatable to the Ocmulgee Formation. There are differences between the sediments in Oaky Woods and those at Taylors Bluff, but most formations show minor variations at geographically different facies and 11 air miles separates Oaky Woods and Taylors Bluff.

Georgia’s Latest Eocene Sediments

The Ocmulgee Formation was studied by Sam Pickering in 1970 during his research in the Hawkinsville area but Pickering referred to it as the Coopers Marl. Pickering also reported that it was locally the most variable “The Cooper Marl shows more facies change in the area studied than any other exposed formation. Thus, the fauna of the Cooper is more varied than the fauna of other formations studied.”

The Ocmulgee Formation was studied by Sam Pickering in 1970 during his research in the Hawkinsville area but Pickering referred to it as the Coopers Marl. Pickering also reported that it was locally the most variable “The Cooper Marl shows more facies change in the area studied than any other exposed formation. Thus, the fauna of the Cooper is more varied than the fauna of other formations studied.”

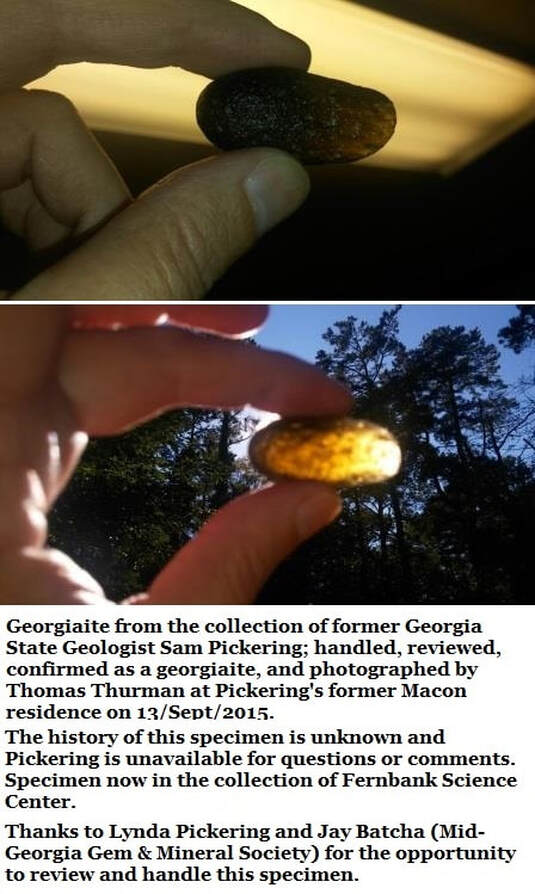

Pickering would go on to do a stint as Georgia State Geologist (1972-1978) and hire the young invertebrate paleontologist Paul Huddlestun to conduct surveys of the Coast Plain. Huddlestun tells the story of being in a brand-new suit for his job interview with the State Geologist, Sam Pickering, and ending up in the field with Sam while wearing his new suit.

As State Geologist, Pickering initiated a wave of field research which persisted well into the 1990s. As part of that research, Huddlestun reassigned the Cooper Marl as the Ocmulgee Formation in 1986.

As State Geologist, Pickering initiated a wave of field research which persisted well into the 1990s. As part of that research, Huddlestun reassigned the Cooper Marl as the Ocmulgee Formation in 1986.

Huddlestun looked closely at the fossil content and dated the Ocmulgee Formation to the uppermost Eocene Epoch, latest Priabonian, at 33.9 million years old. In fact, he showed that three well known sediment beds in central Georgia were being laid down at this time; the Tobacco Road Sand, the Sandersville Limestone, and the Ocmulgee Formation. He assigned the Sandersville Limestone as a member of the Tobacco Road Sand Formation. In 1970 Pickering had been unable to accurately date the Sandersville Limestone, but Huddlestun looked closely and assigned it to the latest Eocene by its fossil suite including, among other factors, its wealth of Periarchus quinquefarius sand dollars.

Importantly, Huddlestun observed that the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation interfingered to form barrier islands at the end of the Eocene Epoch.

Importantly, Huddlestun observed that the Tobacco Road Sand and Ocmulgee Formation interfingered to form barrier islands at the end of the Eocene Epoch.

Horwath

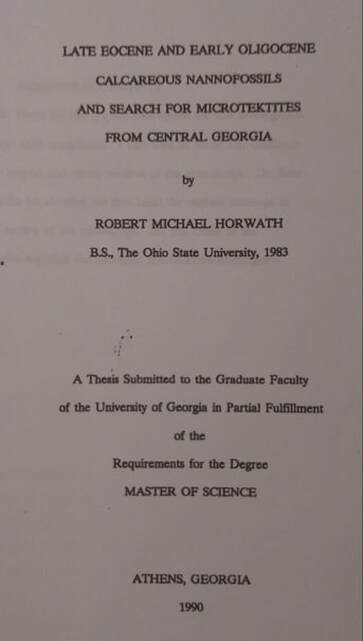

In 1990 Robert M. Horwath was working on his master’s thesis at the University of Georgia and his advisor Vernon Hurst, sent him to find tektites. UGA mistakenly believed that Georgia’s tektites, or georgiaites (www.georgiasfossils.com/14j-georgias-tektites-georgiaites.html) would occur in latest Eocene sediments.

Tektites are essentially meteorite impact debris. Hurst supported a theory popular at UGA that the glacial event which ended the hot house Eocene Epoch was triggered by a meteorite impact event.

That theory was overturned when the age of tektites was firmly established in 1996 by Ed Albin and J.M. Wampler at Fernbank Science Center. They used potassium-argon dating on existing Georgia tektites to show clearly that they dated to 35.2 million years ago, linking them to the meteorite impact event at Chesapeake Bay.

In 1990 Robert M. Horwath was working on his master’s thesis at the University of Georgia and his advisor Vernon Hurst, sent him to find tektites. UGA mistakenly believed that Georgia’s tektites, or georgiaites (www.georgiasfossils.com/14j-georgias-tektites-georgiaites.html) would occur in latest Eocene sediments.

Tektites are essentially meteorite impact debris. Hurst supported a theory popular at UGA that the glacial event which ended the hot house Eocene Epoch was triggered by a meteorite impact event.

That theory was overturned when the age of tektites was firmly established in 1996 by Ed Albin and J.M. Wampler at Fernbank Science Center. They used potassium-argon dating on existing Georgia tektites to show clearly that they dated to 35.2 million years ago, linking them to the meteorite impact event at Chesapeake Bay.

The Eocene Epoch ended 33.9 million years ago. Georgiaites and the Chesapeake Bay Impact Event, both date to 35.2 million years ago. Georgia’s tektites are 1.3 million years too old to be linked to the end-of-Eocene glacial event.

Furthermore, Kenneth Miller, Aimee Pusz (& others) at Rutgers University showed conclusively in 2008 & 2009 that the glacial and extinction event separating the Eocene Epoch & Oligocene Epochs was a natural, global cooling event requiring no extra-terrestrial influence. Essentially, the smoking gun so long sought by so many, isn’t necessary to the explanation.

Horwath, of course, was unaware of these things. He visited all known Ocmulgee Formation sites in his research and carefully took samples. He checked his samples for tektites and nannofossils and eventually reported that the Ocmulgee Formation lacked tektites and that the formation was Late Eocene at its base and Early Oligocene at its top.

Furthermore, Kenneth Miller, Aimee Pusz (& others) at Rutgers University showed conclusively in 2008 & 2009 that the glacial and extinction event separating the Eocene Epoch & Oligocene Epochs was a natural, global cooling event requiring no extra-terrestrial influence. Essentially, the smoking gun so long sought by so many, isn’t necessary to the explanation.

Horwath, of course, was unaware of these things. He visited all known Ocmulgee Formation sites in his research and carefully took samples. He checked his samples for tektites and nannofossils and eventually reported that the Ocmulgee Formation lacked tektites and that the formation was Late Eocene at its base and Early Oligocene at its top.

This, of course, was like throwing a rock in a still pond, and the ripples still abound. Nevertheless, it was wrong. There are problems with Horwath’s findings. The index fossil genus Periarchus occurs in the uppermost Ocmulgee Formation. As mentioned, the genus is restricted to the Late Eocene and has never been reported in the Oligocene, it is a late Eocene guide fossil.

Periarchus did not survive the Eocene glacial event and was extinct by the time the Oligocene opens. Horwath established his dates using nannofossils. Clearly he made some mistake, perhaps in fossil identification. Judging by the notes Huddlestun hand-wrote in the copy of Horwath’s paper given to me, Huddlestun suspects Howarth made several mistakes.

Periarchus did not survive the Eocene glacial event and was extinct by the time the Oligocene opens. Horwath established his dates using nannofossils. Clearly he made some mistake, perhaps in fossil identification. Judging by the notes Huddlestun hand-wrote in the copy of Horwath’s paper given to me, Huddlestun suspects Howarth made several mistakes.

Overcoming Past Errors

All this began when John Trussell, a middle Georgia hunter and writer, led the author to a limestone cliff in Oaky Woods which I tentatively identified as the Ocmulgee Formation. Since I’m an un-degreed amateur I sought professional advice and in time I managed to get Paul Huddlestun in front of the limestone cliff and he agreed that this was Ocmulgee Formation limestone.

Over the course of a couple of years a team was assembled, a paper was written and submitted to Southeastern Geology to announce the presence of new Ocmulgee Formation facies available to researchers. Since I had initiated all of this I proudly stood as the lead author. Up to this point the only known, large Ocmulgee Formation outcrop was on the river at Taylors Bluff.

Typically, when a paper is submitted to a science journal the lead author is contacted directly by the editors over rejection or acceptance. In this case, Lucy Edwards, one of the reviewers, contacted Paul Huddlestun (her old friend) and informed him that there prominent Georgia geologists which maintained that the Ocmulgee Formation was Early Oligocene.

Huddlestun called me, he then began a quest to track down the paper which dated the Ocmulgee Formation to the Oligocene. That proved to be Horwath’s unpublished 1990 Master’s Thesis advised by Vernon Hurst.

All this began when John Trussell, a middle Georgia hunter and writer, led the author to a limestone cliff in Oaky Woods which I tentatively identified as the Ocmulgee Formation. Since I’m an un-degreed amateur I sought professional advice and in time I managed to get Paul Huddlestun in front of the limestone cliff and he agreed that this was Ocmulgee Formation limestone.

Over the course of a couple of years a team was assembled, a paper was written and submitted to Southeastern Geology to announce the presence of new Ocmulgee Formation facies available to researchers. Since I had initiated all of this I proudly stood as the lead author. Up to this point the only known, large Ocmulgee Formation outcrop was on the river at Taylors Bluff.

Typically, when a paper is submitted to a science journal the lead author is contacted directly by the editors over rejection or acceptance. In this case, Lucy Edwards, one of the reviewers, contacted Paul Huddlestun (her old friend) and informed him that there prominent Georgia geologists which maintained that the Ocmulgee Formation was Early Oligocene.

Huddlestun called me, he then began a quest to track down the paper which dated the Ocmulgee Formation to the Oligocene. That proved to be Horwath’s unpublished 1990 Master’s Thesis advised by Vernon Hurst.

Oaky Woods

The Ocmulgee Formation occurs in Houston County’s Oaky Woods Wildlife Management Area. These deposits are 11 air miles (18km) NW of Taylors Bluff. To date, they haven’t yet been officially reported in the research literature.

Huddlestun was unaware of these exposures in 1986.

Horwath was unaware of these in 1990.

The Oaky Woods exposures occur in multiple locations in the wildlife management area and they’re variable in nature.

The Ocmulgee Formation occurs in Houston County’s Oaky Woods Wildlife Management Area. These deposits are 11 air miles (18km) NW of Taylors Bluff. To date, they haven’t yet been officially reported in the research literature.

Huddlestun was unaware of these exposures in 1986.

Horwath was unaware of these in 1990.

The Oaky Woods exposures occur in multiple locations in the wildlife management area and they’re variable in nature.

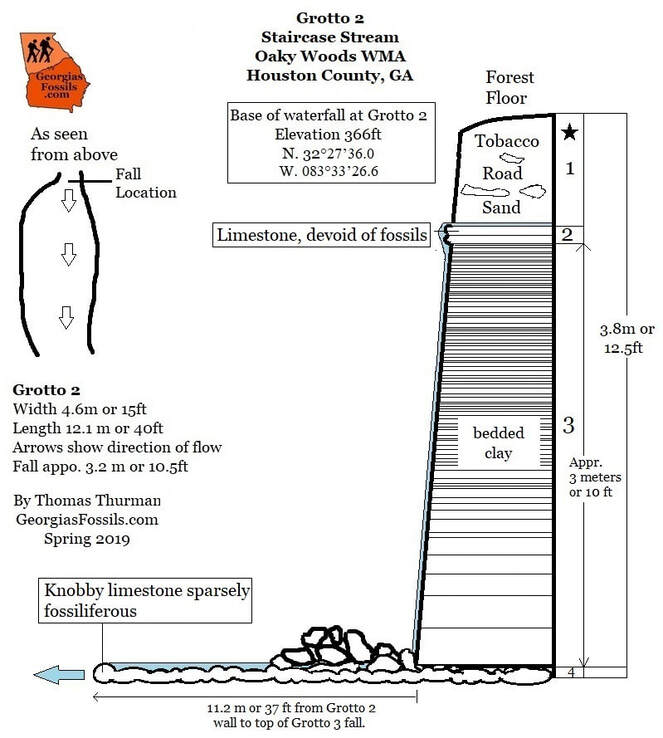

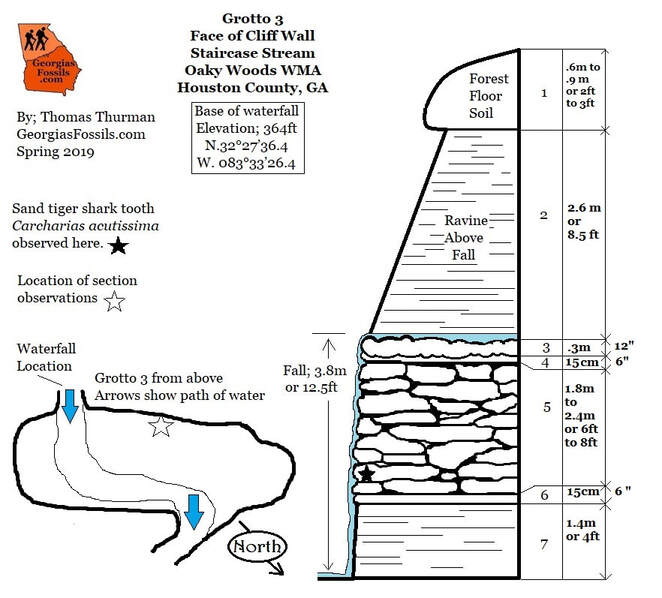

There’s a series of low cliffs in one area, a hilltop exposure in a second area, and the erosional, rain-fed, “Staircase Stream” in a third area. The whole purpose of our river trip was an attempt at clarification and correlation of the sediments at Taylors Bluff with the sediments in Oaky Woods.

In November 2015 the author guided Paul Huddlestun and Don Thieme (Valdosta State University) to the low cliff exposures in Oaky Woods and Huddlestun confirmed them as Ocmulgee Formation. Huddlestun has also visited Staircase Stream where the sediments are highly variable and complex.

If Oaky Woods represents a coastal, barrier island environment in the latest Eocene it would seem that the Ocmulgee Formation at Taylors Bluff, 11 miles southeast, was probably a more offshore, shallow carbonate environment.

In November 2015 the author guided Paul Huddlestun and Don Thieme (Valdosta State University) to the low cliff exposures in Oaky Woods and Huddlestun confirmed them as Ocmulgee Formation. Huddlestun has also visited Staircase Stream where the sediments are highly variable and complex.

If Oaky Woods represents a coastal, barrier island environment in the latest Eocene it would seem that the Ocmulgee Formation at Taylors Bluff, 11 miles southeast, was probably a more offshore, shallow carbonate environment.

End of Eocene

The hot-house Eocene Epoch ended 33.9 million years ago with the extinction event which initiated the cooler Oligocene Epoch. The transition was an extensive glacial episode where so much water was bound in ice that a dramatic fall in sea-levels occurred

Coastlines had been as much as 100ft (30 meters) above today’s levels and they fell to at least 100ft (30 meters) below current levels. They likely withdrew all the way to the Continental Shelf. This natural cooling event probably saw large scale storms which would have repeatedly buffeted and drenched the barrier islands that would later become the Oaky Woods WMA hilltops.

The hot-house Eocene Epoch ended 33.9 million years ago with the extinction event which initiated the cooler Oligocene Epoch. The transition was an extensive glacial episode where so much water was bound in ice that a dramatic fall in sea-levels occurred

Coastlines had been as much as 100ft (30 meters) above today’s levels and they fell to at least 100ft (30 meters) below current levels. They likely withdrew all the way to the Continental Shelf. This natural cooling event probably saw large scale storms which would have repeatedly buffeted and drenched the barrier islands that would later become the Oaky Woods WMA hilltops.

It would seem to the author that coastal, barrier island, Oaky Woods of the latest Eocene would have developed far more complex and variable stratigraphy than the contemporary, shallow, marine Taylors Bluff location 11 air-miles off the coast.

After a good run 5 exhausted paddlers were happy to see the two bridges at Hawkinsville, the boat landing wasn’t far now. We hauled out at Mile Branch Park and around 3:00 pm. Cold drinks, air-conditioning and good food were next orders of business after a day on the river.

After a good run 5 exhausted paddlers were happy to see the two bridges at Hawkinsville, the boat landing wasn’t far now. We hauled out at Mile Branch Park and around 3:00 pm. Cold drinks, air-conditioning and good food were next orders of business after a day on the river.

So Many Thanks!

I want to thank Hank Josey for his tireless help in the field, Dr. Paul Huddlestun, Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern, Dr. Don Thieme at Valdosta State University, and Dr. Roger Portell at Florida Museum of Natural History for their advice and patience with my questions.

I want to thank Hank Josey for his tireless help in the field, Dr. Paul Huddlestun, Dr. Burt Carter at Georgia Southwestern, Dr. Don Thieme at Valdosta State University, and Dr. Roger Portell at Florida Museum of Natural History for their advice and patience with my questions.

References;

- Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central and Eastern Georgia, Huddlestun, Paul F. and Hetrick, John H., Bulletin 95, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1986

- Late Eocene and Early Oligocene Calcareous Nannofossils and Search for Microtektites From Central Georgia; Howarth, Robert Michael, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE, 1990 (Unpublished)

- New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

- Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; Pickering, S. M., Bulletin 81, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1970

- Stratigraphy of the Tobacco Road Sand – A New Formation; Huddlestun, Paul F. & Hetrick, John H.; Short Contributions to the Geology of Georgia, Bulletin 93, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1978

- The Oligocene, A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; Huddlestun, Paul F., Bulletin 105, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1993

- Eocene-Oligocene global climate and sea level changes: St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama. Kenneth G. Miller, James V. Browning, Marie-Pierre Aubry, Bridget S. Wade, Miriam E. Katz, Andrew A. Kulpecz & James D. Wright. Geological Society of America Bulletin, January/February 2008.

- Stable Isotopic Response to Late Eocene Extraterrestrial Impacts. Aimee E. Pusz, Kenneth G. Miller, James D. Wright, Miriam E. Katz, Benjamin S. Cramer, Dennis V. Kent. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 452, 2009