20: The Ice Ages

The Quaternary Period

By Thomas Thurman

Pleistocene and Holocene Epoch

Pleistocene: 2.5 million years ago through 12,000 years ago

Holocene: 12,000 years ago to present day

Pleistocene: 2.5 million years ago through 12,000 years ago

Holocene: 12,000 years ago to present day

By the Pleistocene the continents were generally within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of their modern positions and essentially as we see them today.

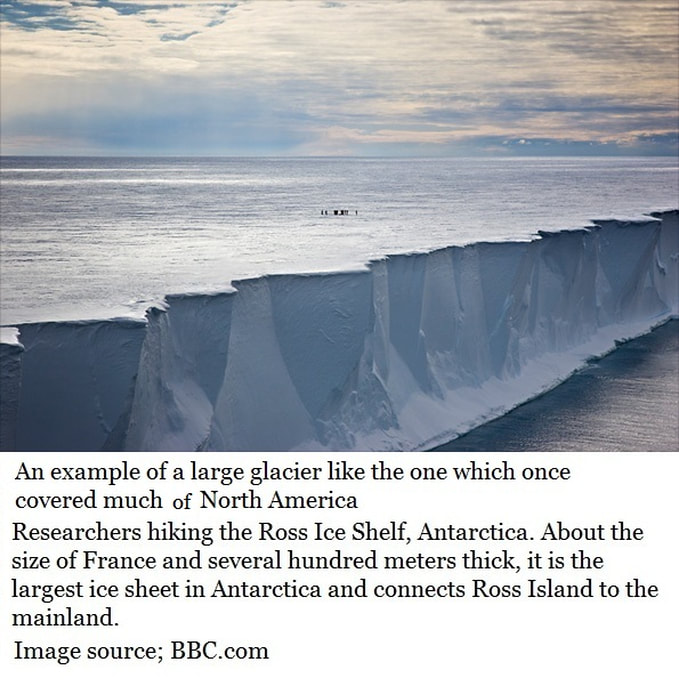

The Pleistocene Epoch saw the most frequent and severe cycles of glaciation. The theories explaining this are complex and were discussed in general terms in the Pliocene entry, but a repeated cycle of global glaciation occurred at least every 100,000 years.

This is the Milankovitch Cycle, named after Serbian geophysicist and astronomer Milutin Milanković who worked on the theory during the First World War.

The Pleistocene Epoch saw the most frequent and severe cycles of glaciation. The theories explaining this are complex and were discussed in general terms in the Pliocene entry, but a repeated cycle of global glaciation occurred at least every 100,000 years.

This is the Milankovitch Cycle, named after Serbian geophysicist and astronomer Milutin Milanković who worked on the theory during the First World War.

Georgia’s Pleistocene Residents

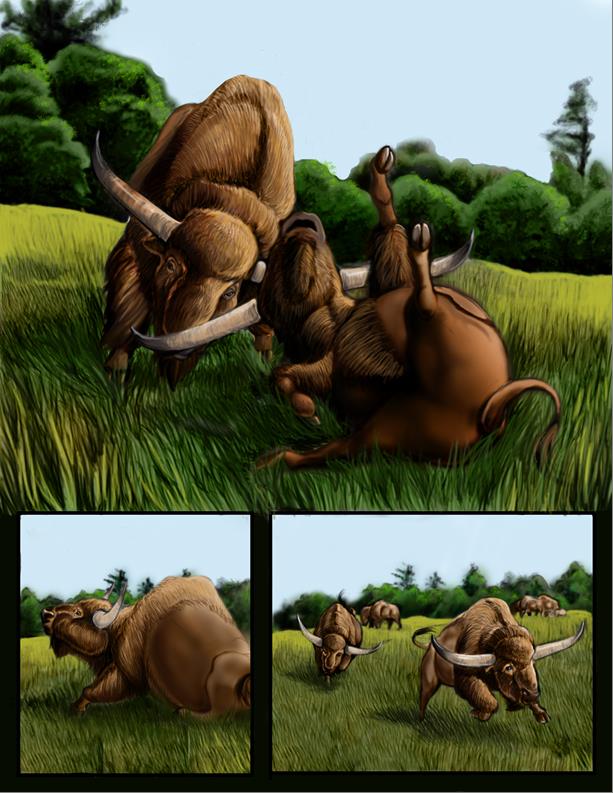

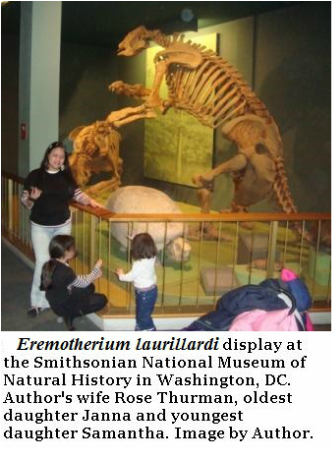

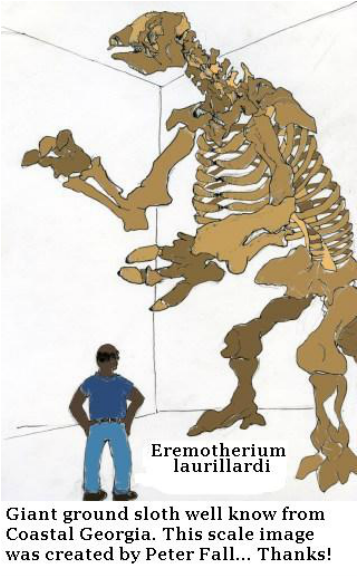

The giant ground sloth; Eremotherium laurillardi was one of Georgia’s true ice age giants. Believed to be capable of walking either on all four or hind legs, this was a ground sloth which fed on trees.

There are tracks showing Megatherium, a South American relative, walking on its hind legs. At about 20 feet tall standing erect, South America’s Megatherium (which was actually a tree sloth) was still slightly smaller than Georgia’s Eremotherium which might have reached 21 feet, taller than most houses and twice the height of a modern elephant.

Eremotherium laurillardi was taller by far than any other known Pleistocene animals of the Southeast.

The bones are huge, heavy and massive. The hind legs and a thick, a muscular tail evolved to support the animal’s great weight in a tripod arrangement when it was upright against a tree feeding.

Megatherium has been estimated to eight tons, Eremotherium would have at least equaled this weight.

The giant ground sloth; Eremotherium laurillardi was one of Georgia’s true ice age giants. Believed to be capable of walking either on all four or hind legs, this was a ground sloth which fed on trees.

There are tracks showing Megatherium, a South American relative, walking on its hind legs. At about 20 feet tall standing erect, South America’s Megatherium (which was actually a tree sloth) was still slightly smaller than Georgia’s Eremotherium which might have reached 21 feet, taller than most houses and twice the height of a modern elephant.

Eremotherium laurillardi was taller by far than any other known Pleistocene animals of the Southeast.

The bones are huge, heavy and massive. The hind legs and a thick, a muscular tail evolved to support the animal’s great weight in a tripod arrangement when it was upright against a tree feeding.

Megatherium has been estimated to eight tons, Eremotherium would have at least equaled this weight.

With heavy front paws, as large as a big man’s chest and equipped with long claws, the powerful Eremotherium had no trouble dealing with trees.

Long front legs meant that it was not only capable of shredding trees but would likely have been a formidable challenge for any predators.

Beyond its great size there is no evidence to suggest that this was a slow moving animal.

Eremotherium is known from Coastal Georgia. It went extinct about 10,000 years ago with most of the other megafauna of the ice ages.

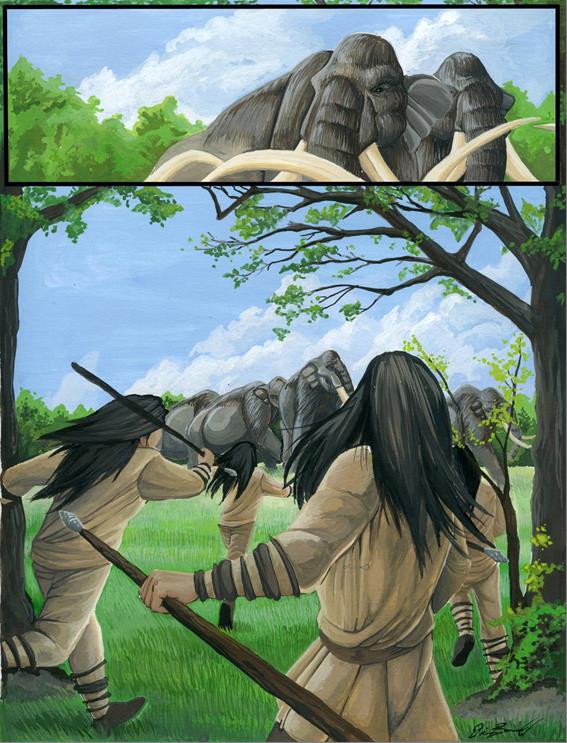

In all likelihood the earliest currently known Georgians, the Clovis people, would have known of Eremotherium though there is no evidence that the sloth was hunted or that they ever interacted.

I want to thank Peter Fall, a talented art student at Georgia Southwestern State University for his many 2011 efforts to illustrate Eremotherium laurillardi a difficult subject. We exchanged many lively emails in this process.

Long front legs meant that it was not only capable of shredding trees but would likely have been a formidable challenge for any predators.

Beyond its great size there is no evidence to suggest that this was a slow moving animal.

Eremotherium is known from Coastal Georgia. It went extinct about 10,000 years ago with most of the other megafauna of the ice ages.

In all likelihood the earliest currently known Georgians, the Clovis people, would have known of Eremotherium though there is no evidence that the sloth was hunted or that they ever interacted.

I want to thank Peter Fall, a talented art student at Georgia Southwestern State University for his many 2011 efforts to illustrate Eremotherium laurillardi a difficult subject. We exchanged many lively emails in this process.

Georgia’s Ice Age Whales

While corresponding with Dr. Mark Uhen during May 2011 he mentioned two ice age Georgia whale fossils I wasn’t previously aware of, I want to thank him for giving me the genus and species names.

During the ice ages of the Pleistocene Epoch different whales occurred in Georgia’s fossil record. As we’ve seen with the Smithsonian report on Georgia Pleistocene fossils; populations of both sperm whales and dolphins were also present.

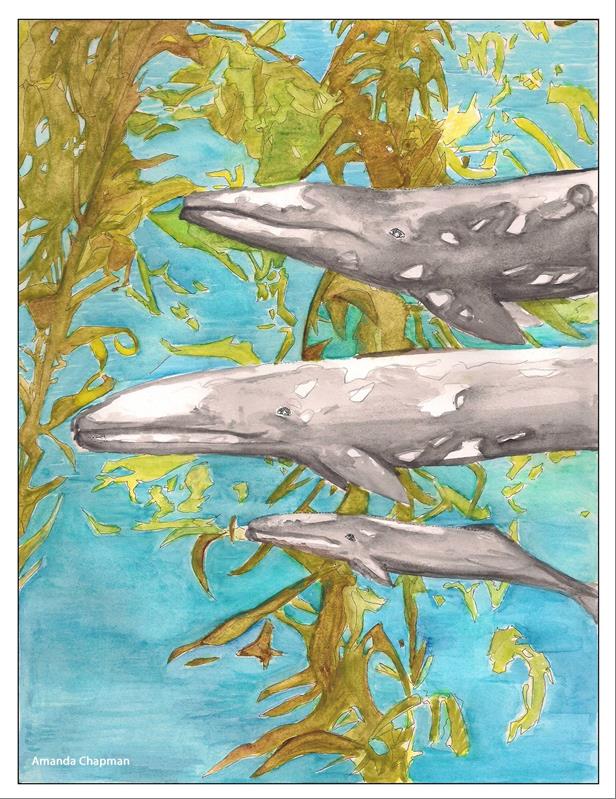

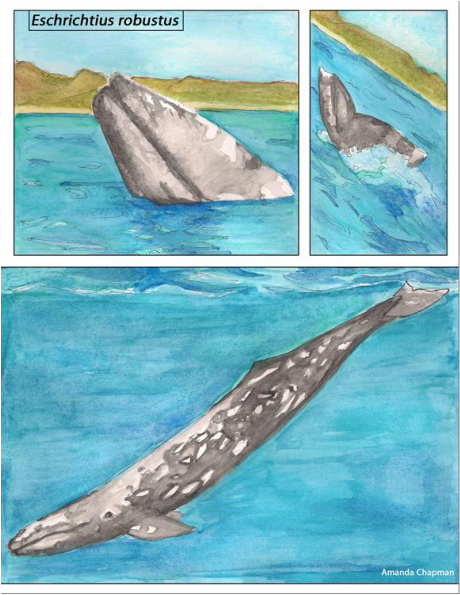

The modern gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus, also swam in Georgia’s sea. A baleen whale, the modern gray whale emerges into the fossil record during the Pleistocene.

It eats crustaceans which it scoops up from the bottom. Many researchers consider this type of feeding the primitive origin of all baleen whales. Averaging 52 feet in length it no longer occurs in the Atlantic but is only known from the northern Pacific. Whalers called it the devil fish for its tendency to fight ferociously.

Amanda Chapman created these images of the gray whale during the 2012 Commercial Illustration Project at Georgia Southwestern in Americus.

While corresponding with Dr. Mark Uhen during May 2011 he mentioned two ice age Georgia whale fossils I wasn’t previously aware of, I want to thank him for giving me the genus and species names.

During the ice ages of the Pleistocene Epoch different whales occurred in Georgia’s fossil record. As we’ve seen with the Smithsonian report on Georgia Pleistocene fossils; populations of both sperm whales and dolphins were also present.

The modern gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus, also swam in Georgia’s sea. A baleen whale, the modern gray whale emerges into the fossil record during the Pleistocene.

It eats crustaceans which it scoops up from the bottom. Many researchers consider this type of feeding the primitive origin of all baleen whales. Averaging 52 feet in length it no longer occurs in the Atlantic but is only known from the northern Pacific. Whalers called it the devil fish for its tendency to fight ferociously.

Amanda Chapman created these images of the gray whale during the 2012 Commercial Illustration Project at Georgia Southwestern in Americus.

Beaked Whale

Our Pleistocene sediments also hosted the extinct beaked whale Anoplonassa forcipata.

The specimen Georgia produced founded the species and is currently the only known example. It is a 7.5 inch long portion of a jaw bone housed in the collection of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge, Massachusetts as specimen number MCZ 8766, its continued presence was confirmed by Jessica D. Cundiff, Acting Curatorial Associate, Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

It was collected and described by the famous American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. We met Cope earlier when he came to Georgia to view and describe the Agomphus oxysternum turtle carapace from Montezuma.

The record on this find is a bit confused. By one of Cope’s reports the beaked whale fossil was discovered near Savannah with the remains of a mastodon. By another of Cope’s reports it was discovered in 1890, among phosphatic deposits in South Carolina.

In 1907 the cetacean researcher Frederick W. True, whom we’ve also met, dismissed the South Carolina report as a mistake as it did not represent the specimen accurately so the Savannah report is upheld.

Modern beaked whales are among the most interesting, least understood, and rarest of the toothed whales. There are living species which have yet to be fully described by science and are only known from decayed beached carcasses.

They range from 13 to 43 feet long and are known for long duration deep dives lasting more than an hour and reaching depths exceeding a mile.

They are rarely seen in the wild, tend toward deep sea environments and only congregate along continental shelves.

Our Pleistocene sediments also hosted the extinct beaked whale Anoplonassa forcipata.

The specimen Georgia produced founded the species and is currently the only known example. It is a 7.5 inch long portion of a jaw bone housed in the collection of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge, Massachusetts as specimen number MCZ 8766, its continued presence was confirmed by Jessica D. Cundiff, Acting Curatorial Associate, Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

It was collected and described by the famous American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. We met Cope earlier when he came to Georgia to view and describe the Agomphus oxysternum turtle carapace from Montezuma.

The record on this find is a bit confused. By one of Cope’s reports the beaked whale fossil was discovered near Savannah with the remains of a mastodon. By another of Cope’s reports it was discovered in 1890, among phosphatic deposits in South Carolina.

In 1907 the cetacean researcher Frederick W. True, whom we’ve also met, dismissed the South Carolina report as a mistake as it did not represent the specimen accurately so the Savannah report is upheld.

Modern beaked whales are among the most interesting, least understood, and rarest of the toothed whales. There are living species which have yet to be fully described by science and are only known from decayed beached carcasses.

They range from 13 to 43 feet long and are known for long duration deep dives lasting more than an hour and reaching depths exceeding a mile.

They are rarely seen in the wild, tend toward deep sea environments and only congregate along continental shelves.

Back to Hannahatchee Creek

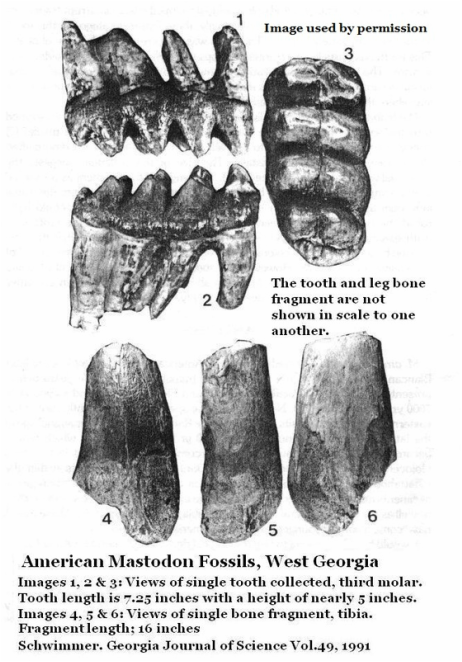

Returning to the area of Hannahatchee Creek, in 1986 amateurs found an unexpected mastodon tooth and a partial leg bone. This was a surprise since ice age (Pleistocene) fossils weren’t previously known to occur in the area.

The mastodon tooth was collected by Jimmy Stafford of Lumpkin, Georgia and the leg bone was collected separately by Len and Josephine Lee of Omaha, Georgia.

Both were loaned to Dr. David Schwimmer at Columbus State University for study but remain in private collections.

A cast of the tooth was made for research purposes and that can be seen at Tellus Museum in Cartersville, Georgia. The research paper on these finds was published in 1991 by the Georgia Journal of Science.

To quote Dr. Schwimmer’s report. “The molar features a complete crown and nearly complete roots… relatively little alteration other than the striking blue-black mineral coloration of the crown… the tooth roots retain the typical off-white color of fresh ivory.”

Returning to the area of Hannahatchee Creek, in 1986 amateurs found an unexpected mastodon tooth and a partial leg bone. This was a surprise since ice age (Pleistocene) fossils weren’t previously known to occur in the area.

The mastodon tooth was collected by Jimmy Stafford of Lumpkin, Georgia and the leg bone was collected separately by Len and Josephine Lee of Omaha, Georgia.

Both were loaned to Dr. David Schwimmer at Columbus State University for study but remain in private collections.

A cast of the tooth was made for research purposes and that can be seen at Tellus Museum in Cartersville, Georgia. The research paper on these finds was published in 1991 by the Georgia Journal of Science.

To quote Dr. Schwimmer’s report. “The molar features a complete crown and nearly complete roots… relatively little alteration other than the striking blue-black mineral coloration of the crown… the tooth roots retain the typical off-white color of fresh ivory.”

For these reasons Schwimmer suspects that the animal lived towards the end of the mastodon’s extent as a species, say 12,000 years ago.

In the late summer of 2010 the author contacted both Jimmy Stafford and Josephine Lee, each reported that these fossils are safe and still in their possession. At that time the tooth is still in the box which Schwimmer had used to return the specimen.

This was Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon, the size comparisons of the two fossils suggest that they could have come from the same adult individual. Fossils from this species and time frame are known from North, West and Coastal Georgia (even well off the coast of Georgia at Grey’s Reef).

Mastodons emerge into the fossil record about 3.7 million years ago and the American mastodon is the most recent species, it went extinct with many other large animals about 10,000 years ago. Between 12,000 to 15,000 years ago large populations were known to be in Georgia.

As of the summer of 2010, Dr. Schwimmer was aware of no other Pleistocene finds from the area and would certainly be interested in seeing additional specimens.

When this mastodon likely lived 12,000 years ago the sea level was at or below modern levels and the most recent ice age was receding.

Georgia’s rivers ran much deeper and wider than today, heavily swollen with rain water from glacial melt. The high ground around the Chattahoochee Valley was heavily forested and mastodons walked in those forests.

On 02/June/2013 Dr. Schwimmer commented that another mastodon site had been reported in West Georgia by a tusk find, but the specimen had not be reviewed by scientists and is therefore not a verifiable discovery.

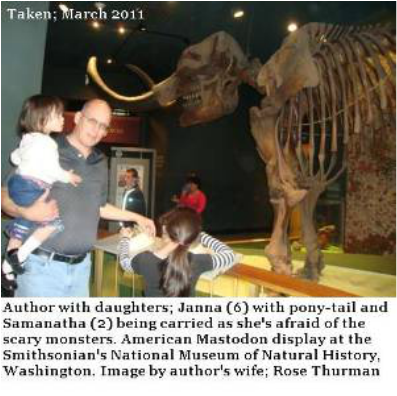

The American Mastodon is only distantly related to mammoths and elephants. Mammoths (as in the movie Ice Age) and elephants are closely related to each other as both are grazers, eating grass.

Mastodons were browsers eating brush and leaves, the peaked crowns of their teeth are distinctly different from the flat, grooved tooth crowns of elephants and mammoths.

We looked briefly at the coastal fossil research by Richard Hulbert and Ann Pratt and saw some of the Pliocene and Miocene fossils they found while they searched for the ice age Pleistocene material.

Several researchers have done similar Pleistocene work, often as follow-ups from field reports by amateurs or people finding things on their property. Combining this research generates a good representation of Georgia’s animal life during the Pleistocene. The following lists come from finds across the state and represent coastal and inland reports including cave finds from Bartow County’s Ladds Mountain area.

It is interesting to look through the list and see animals which remain in Georgia, animals which remain but no longer occur in Georgia like caribou and reindeer, animals like the cougar which may be returning to Georgia and the animals like the giant sloths which are gone forever.

In the late summer of 2010 the author contacted both Jimmy Stafford and Josephine Lee, each reported that these fossils are safe and still in their possession. At that time the tooth is still in the box which Schwimmer had used to return the specimen.

This was Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon, the size comparisons of the two fossils suggest that they could have come from the same adult individual. Fossils from this species and time frame are known from North, West and Coastal Georgia (even well off the coast of Georgia at Grey’s Reef).

Mastodons emerge into the fossil record about 3.7 million years ago and the American mastodon is the most recent species, it went extinct with many other large animals about 10,000 years ago. Between 12,000 to 15,000 years ago large populations were known to be in Georgia.

As of the summer of 2010, Dr. Schwimmer was aware of no other Pleistocene finds from the area and would certainly be interested in seeing additional specimens.

When this mastodon likely lived 12,000 years ago the sea level was at or below modern levels and the most recent ice age was receding.

Georgia’s rivers ran much deeper and wider than today, heavily swollen with rain water from glacial melt. The high ground around the Chattahoochee Valley was heavily forested and mastodons walked in those forests.

On 02/June/2013 Dr. Schwimmer commented that another mastodon site had been reported in West Georgia by a tusk find, but the specimen had not be reviewed by scientists and is therefore not a verifiable discovery.

The American Mastodon is only distantly related to mammoths and elephants. Mammoths (as in the movie Ice Age) and elephants are closely related to each other as both are grazers, eating grass.

Mastodons were browsers eating brush and leaves, the peaked crowns of their teeth are distinctly different from the flat, grooved tooth crowns of elephants and mammoths.

We looked briefly at the coastal fossil research by Richard Hulbert and Ann Pratt and saw some of the Pliocene and Miocene fossils they found while they searched for the ice age Pleistocene material.

Several researchers have done similar Pleistocene work, often as follow-ups from field reports by amateurs or people finding things on their property. Combining this research generates a good representation of Georgia’s animal life during the Pleistocene. The following lists come from finds across the state and represent coastal and inland reports including cave finds from Bartow County’s Ladds Mountain area.

It is interesting to look through the list and see animals which remain in Georgia, animals which remain but no longer occur in Georgia like caribou and reindeer, animals like the cougar which may be returning to Georgia and the animals like the giant sloths which are gone forever.

References:

Sea Level change

The Phanerozoic Record of Global Sea-Level Change

Kenneth G. Miller, Michelle A. Kominz, James V. Browning, James D. Wright, Gregory S. Mountain, Miriam E. Katz, Peter J. Sugarman, Benjamin S. Cramer, Nicholas Christie-Blick, Stephen F. Pekar. Science, Vol. 310, 25 Nov 2005

Twenty-seven sea level changes;

A warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider & Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, 2009, Pg. 194, Cambridge Philosophical Society

Eolian Dunes;

Riverine dunes on the Coastal Plain of Georgia, USA. Andrew H. Ivester & David S. Leigh, Geomorphology, 1253, 2002. Published by Elsevier Science B.V

Mystery of the Misplaced Dunes. By Lucy Justus. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine. 22/Feburary/1976 (Sam Pickering advised)

Carolina Bays of Georgia

Van DeGenachte, E., and S. Cammack. 2002. Carolina bays of Georgia: Their distribution, condition, and conservation. Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Social Circle.

Mammut americanum:

First Mastodont remains From the Chattahoochee River Valley in Western Georgia, With Implications for the Age of Adjacent Stream Terraces. David R. Schwimmer. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.49, Pgs.81-86. 2001, Georgia Academy of Sciences

Clark Quarry

Preliminary Comments on the Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Clark Quarry, Brunswick, Georgia. Alfred J. Mead, Robert A. Bahn, Robert M. Chandler and Dennis Parmley. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates, Vol.23. 2006

Sea level change numbers & Southeastern ice age refuge info:

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Lists of Pleistocene Fossils:

New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Early reports from the Georgia Coast:

Prehistoric Vertebrates of the Georgia Coastal Plain. Georgia Mineral Newsletter Vol. X, No. 3, Autumn 1957 By: Vernon Hurst 1957

Sea Level change

The Phanerozoic Record of Global Sea-Level Change

Kenneth G. Miller, Michelle A. Kominz, James V. Browning, James D. Wright, Gregory S. Mountain, Miriam E. Katz, Peter J. Sugarman, Benjamin S. Cramer, Nicholas Christie-Blick, Stephen F. Pekar. Science, Vol. 310, 25 Nov 2005

Twenty-seven sea level changes;

A warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider & Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, 2009, Pg. 194, Cambridge Philosophical Society

Eolian Dunes;

Riverine dunes on the Coastal Plain of Georgia, USA. Andrew H. Ivester & David S. Leigh, Geomorphology, 1253, 2002. Published by Elsevier Science B.V

Mystery of the Misplaced Dunes. By Lucy Justus. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine. 22/Feburary/1976 (Sam Pickering advised)

Carolina Bays of Georgia

Van DeGenachte, E., and S. Cammack. 2002. Carolina bays of Georgia: Their distribution, condition, and conservation. Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Social Circle.

Mammut americanum:

First Mastodont remains From the Chattahoochee River Valley in Western Georgia, With Implications for the Age of Adjacent Stream Terraces. David R. Schwimmer. Georgia Journal of Science, Vol.49, Pgs.81-86. 2001, Georgia Academy of Sciences

Clark Quarry

Preliminary Comments on the Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Clark Quarry, Brunswick, Georgia. Alfred J. Mead, Robert A. Bahn, Robert M. Chandler and Dennis Parmley. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates, Vol.23. 2006

Sea level change numbers & Southeastern ice age refuge info:

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Lists of Pleistocene Fossils:

New Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Vertebrate Fauna from Coastal Georgia. Richard C. Hulbert and Ann E. Pratt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol.18, No.2, pgs 412-429, June 1998. Society of vertebrate Paleontology.

A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Dale A. Russell, Frederick J. Rich, Vincent Schneider and Jean Lynch-Stieglitz. Biological Review, Vol.84, Pgs. 173-202, 2009.

Early reports from the Georgia Coast:

Prehistoric Vertebrates of the Georgia Coastal Plain. Georgia Mineral Newsletter Vol. X, No. 3, Autumn 1957 By: Vernon Hurst 1957