16: Back to Bonaire

and the Terminator Pigs

By Thomas Thurman

November/2014

During the annual 2011 summer picnic of the Mid Georgia Gem and Mineral Society member Ms. Gayla Jackson, a retired science teacher, reported that she’d recently collected shark’s teeth from a new site in Bonaire, Georgia.

This turned out to be a large artificial overburden mound created during the construction of Hilltop Elementary school and the surrounding residential neighborhood.

The local hilltops had been scraped level and the removed material, called overburden, was dumped in a nearby valley. Mrs. Jackson had found shark’s teeth along the edges of this mound.

Half of a fossilized molar was found by the author while exploring the erosion gullies of the overburden mound on 26/June/2011. It seemed to belong to a terrestrial mammal.

I suspected it to be an entelodont tooth but thought that unlikely. To my knowledge none had been reported since the University of Georgia research into the Tivola Limestone and Twiggs Clay during the late 1980s.

The partial tooth appeared to have been broken recently, as the edges of the break were still sharp and the coloration here did not match the weathered damage on the root-tip. It had likely been damaged by heavy equipment during excavation, transportation or dumping of the overburden. Despite exploring up and down the gully and screening several samples, no more material was found. That wasn’t surprising.

Since the overburden mound had mixed Oligocene and Eocene sediments it was impossible to correlate the age of the tooth by stratigraphy.

The tooth was shown to Ashley Quinn; Collections Manager at the Georgia College Natural History Museum in Milledgeville. Ashley also suspected this was an entelodont tooth and compared it to material in the museum’s collection.

The tooth most closely resembled entelodont fossils from the Oligocene, specifically from the genus Archaeotherium which had never been reported from Georgia. Ashley agreed to hold the tooth until the professors returned from summer vacation, she would ask them to review and identify the specimen.

In a few weeks a package came returning my tooth with a letter bearing news that the partial tooth could only be officially identified only to the family level; it indeed compared favorably with entelodonts. There just wasn’t sufficient material for identification to the genus or species level.

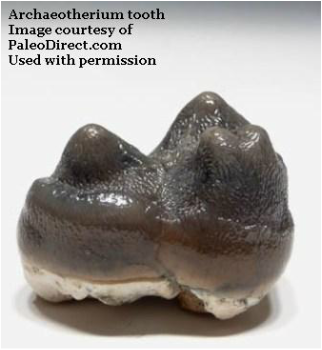

While researching entelodonts I stumbled across this Archaeotherium tooth on PaleoDirect.com. These images were very close to the partial tooth I’d found. (I want to thank John McNamara at PaleoDirect.com for granting permission to use these images.)

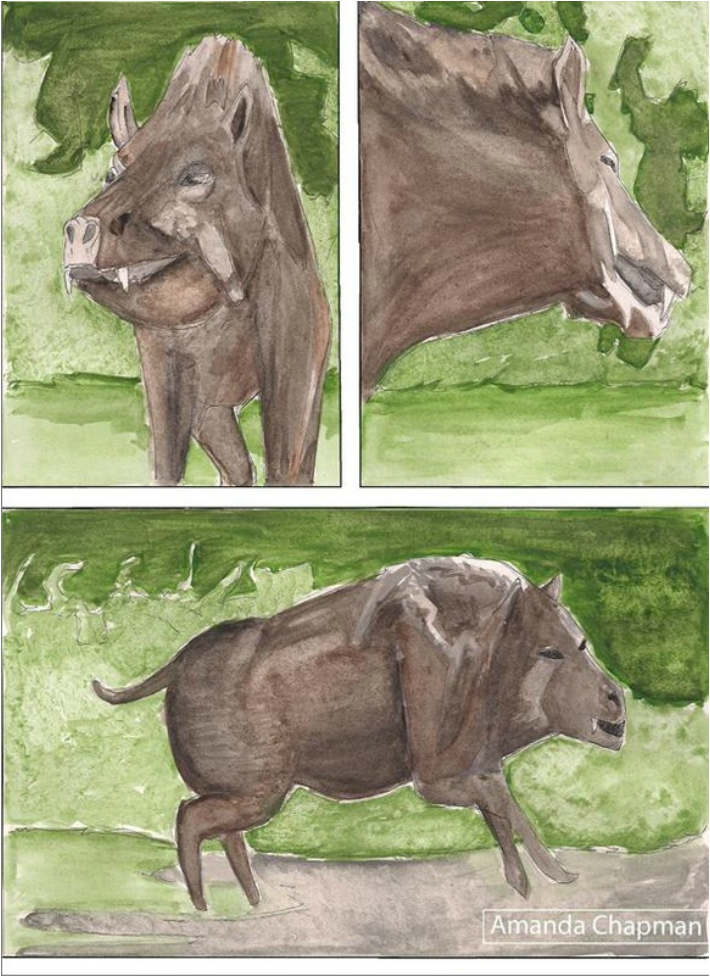

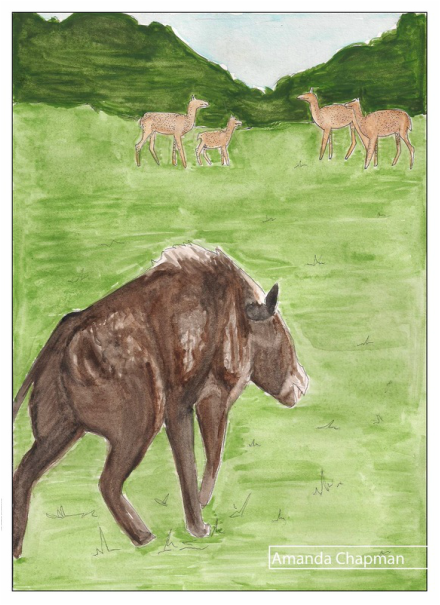

Amanda Chapman joined Professor Laurel Robinson’s advance Visual Arts Class in 2012 and participated in the second year of the Georgia Southwestern commercial art illustration project. Upon reading of my entelodont find she surprised me with the following images after she’d submitted her project illustrations of Georgia’s rhino.

These two paintings of an Archaeotherium were done as additional submissions. The image of it stalking prey is accurate, though the prey represented is intended as generic since we have no information about what prey might have been present in Georgia.

Bear in mind, the tooth I reported to Georgia College can only be officially classified as an entelodont, and there were many entledonts… Also, we don’t know what age sediments originally hosted the tooth since it was recovered from overburden with mixed sediments. We cannot say, with any certainty, that the tooth belonged to an Archaeotherium as illustrated by Miss Chapman….

Still… It is an intriguing thought. Ms. Chapman has my gratitude.

The tooth most closely resembled entelodont fossils from the Oligocene, specifically from the genus Archaeotherium which had never been reported from Georgia. Ashley agreed to hold the tooth until the professors returned from summer vacation, she would ask them to review and identify the specimen.

In a few weeks a package came returning my tooth with a letter bearing news that the partial tooth could only be officially identified only to the family level; it indeed compared favorably with entelodonts. There just wasn’t sufficient material for identification to the genus or species level.

While researching entelodonts I stumbled across this Archaeotherium tooth on PaleoDirect.com. These images were very close to the partial tooth I’d found. (I want to thank John McNamara at PaleoDirect.com for granting permission to use these images.)

Amanda Chapman joined Professor Laurel Robinson’s advance Visual Arts Class in 2012 and participated in the second year of the Georgia Southwestern commercial art illustration project. Upon reading of my entelodont find she surprised me with the following images after she’d submitted her project illustrations of Georgia’s rhino.

These two paintings of an Archaeotherium were done as additional submissions. The image of it stalking prey is accurate, though the prey represented is intended as generic since we have no information about what prey might have been present in Georgia.

Bear in mind, the tooth I reported to Georgia College can only be officially classified as an entelodont, and there were many entledonts… Also, we don’t know what age sediments originally hosted the tooth since it was recovered from overburden with mixed sediments. We cannot say, with any certainty, that the tooth belonged to an Archaeotherium as illustrated by Miss Chapman….

Still… It is an intriguing thought. Ms. Chapman has my gratitude.

Dr. David Schwimmer at Columbus State University suggested I contact Dr. Bruce MacFadden, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Dr. MacFadden was happy to help.

03/Aug/2011

Thomas;

This tooth fragment is not a lot to go on. It could be Archaeotherium, but more comparisons with existing collections are warranted. This potentially is an interesting find for the Georgia fossil record. I hope this helps.

Bruce J. MacFadden, Ph.D.

Curator and Professor

Florida Museum of Natural History

University of Florida

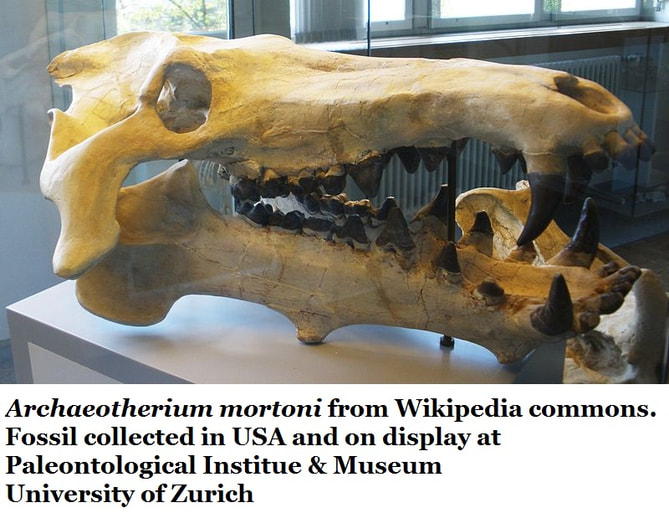

Archaeotherium (Greek; Ancient Beast) is a genus in the entelodont family only known from North America but it was once widespread across the continent.

It is a smaller entelodont with the largest species being Archaeotherium mortoni, reaching about 4 feet high at the shoulders and about 6 feet in length; essentially the size of a bull but with carnivorous tendencies.

Research suggests that the genus Archaeotherium continued the omnivorous feeding habits of other entelodonts; eating roots and tubers as well as actively hunting. Evidence from the Wyoming Dinosaur Center (Archaeotherium was not a dinosaur but a mammal like us.) reports that caches of food were kept by Archaeotherium which included bones from prey mammals; this behavior is also seen in several modern predators.

Fossils of North American rhinos from the same timeframe as Archaeotherium have been found in the western United States with bite marks matching the entelodont’s large canine teeth. There is also a series of track ways at Toadstool Geologic Park in the Oglala National Grassland (northwestern Nebraska) which seems to depict a cow-sized American rhino (Genus; Subhyracodon) walking along, crouching as it senses an Archaeotherium, then breaking into a gallop with the entelodont in pursuit.

While the entelodont family occurs in the fossil record until the Miocene 16.5 million years ago, the genus Archaeotherium did not survive beyond the earliest Oligocene.

It is a smaller entelodont with the largest species being Archaeotherium mortoni, reaching about 4 feet high at the shoulders and about 6 feet in length; essentially the size of a bull but with carnivorous tendencies.

Research suggests that the genus Archaeotherium continued the omnivorous feeding habits of other entelodonts; eating roots and tubers as well as actively hunting. Evidence from the Wyoming Dinosaur Center (Archaeotherium was not a dinosaur but a mammal like us.) reports that caches of food were kept by Archaeotherium which included bones from prey mammals; this behavior is also seen in several modern predators.

Fossils of North American rhinos from the same timeframe as Archaeotherium have been found in the western United States with bite marks matching the entelodont’s large canine teeth. There is also a series of track ways at Toadstool Geologic Park in the Oglala National Grassland (northwestern Nebraska) which seems to depict a cow-sized American rhino (Genus; Subhyracodon) walking along, crouching as it senses an Archaeotherium, then breaking into a gallop with the entelodont in pursuit.

While the entelodont family occurs in the fossil record until the Miocene 16.5 million years ago, the genus Archaeotherium did not survive beyond the earliest Oligocene.

The problem rests in confirming the partial tooth as belonging to an Archaeotherium. Unfortunately multiple attempts to compare it, or have it compared, with specimens possibly in the University of Georgia collection were unsuccessful; attempts to contact the Geology Department and the Georgia Natural History Museum were not replied to. So how this tooth might compare to Voorhies’ specimens, if they still exist, is unknown.

Looking elsewhere, Badlands National Park in South Dakota has a strong fossil record of entelodonts; especially Archaeotherium.

In 2012 I received a reply from Ms. Connie Wolf, their Administration Assistant. She referred me on to Dr. Scott Foss who’d completed his dissertation on entelodont phylogeny (comparative development of a species). Dr. Foss was kind enough to review these images of the tooth, his reply is below:

14/Nov/2012

Hello Thomas:

I have looked at the images and I can’t do much more than verify that it does appear to be entelodont. I would suggest that it is a small-to-medium sized individual, but not a juvenile. However, the excellent preservation could be a result of it being a rather young animal. The M3 (tooth position) is that last molar to erupt, so it could be a young adult. There is a little bit of wear on the cusp (metacone?), so the animal did have use of the tooth for some time. Without knowing its local diet it’s difficult to know if it was chewing soft food for a long time, or coarse food for a shorter time. The lack of chips or obvious scrapes on the tooth suggest the former to me, but that’s speculation.

I was unaware of entelodont discoveries in Georgia, so geographically this is a significant discovery. As others have said, the tooth lacks enough diagnostic traits to identify it beyond the family level (Entelodontidae), but if it is in fact from Oligocene sediments, Archaeotherium is a reasonable assignment.

By the way, Achaenodon has four well-defined cusps and a strong posterior shelf. I do not think the tooth looks like Achaenodon.

Scott E. Foss, PhD

Regional Paleontologist

BLM Utah State Office

PO Box 45155

Salt Lake City, UT 84105

I’m grateful to Dr. Foss and Ms. Wolf for their assistance. With the comment from Dr. Foss about being unaware of Georgia’s entelodonts and Dr. MacFadden’s comment that this was a potentially interesting find for Georgia I thought I should try to have something published in the scientific literature.

Bearing in mind that I’m an amateur paleontologist, not a professional researcher, I assembled a short piece including both of the above emails and submitted it to the Georgia Journal of Science, a publication for the Georgia Academy of Sciences, of which I was a member at the time.

2/Dec/2012

Thomas,

Hello.

I admire your efforts, but the Georgia Journal of Science publishes original, professional research.

Thanks,

John V. Aliff, Ph.D.

Professor of Biology, Georgia Perimeter College

Editor, Georgia Journal of Science

An attempt to have something published in Southeastern Geology, published by Duke University’s Geology Department (now Earth and Ocean Sciences) earned a reply from the Editor-in-Chief that he would forward my proposal to the Editor, but there was only silence after that.

It can be very difficult for amateurs to get into professional publications.

In 2014 I submitted images of the tooth on Facebook’s; The Fossil Forum where I am a member. Richard S. White, one of the Fossil Forum’s administrators, became curious over my find and with his advice I contacted Dr. Richard C. Hulbert at the Florida Museum of Natural History and Dr. Hulbert agreed to review the tooth. As of this writing (Nov. 2014) Dr. Hulbert has the partial tooth and I’d prefer it remain in Georgia; I’ll likely donate it permanently to the Florida Museum of Natural History as they have shown interest in it. There, it will be available to future researchers.

I’m standing happily on my entelodont identification while urging others to be aware and watch for entelodont fossils; if the Oligocene Epoch Archaeotherium could be confirmed in Georgia it would be a scientifically important find. This single, partial tooth just isn’t enough material for such a claim.

Looking elsewhere, Badlands National Park in South Dakota has a strong fossil record of entelodonts; especially Archaeotherium.

In 2012 I received a reply from Ms. Connie Wolf, their Administration Assistant. She referred me on to Dr. Scott Foss who’d completed his dissertation on entelodont phylogeny (comparative development of a species). Dr. Foss was kind enough to review these images of the tooth, his reply is below:

14/Nov/2012

Hello Thomas:

I have looked at the images and I can’t do much more than verify that it does appear to be entelodont. I would suggest that it is a small-to-medium sized individual, but not a juvenile. However, the excellent preservation could be a result of it being a rather young animal. The M3 (tooth position) is that last molar to erupt, so it could be a young adult. There is a little bit of wear on the cusp (metacone?), so the animal did have use of the tooth for some time. Without knowing its local diet it’s difficult to know if it was chewing soft food for a long time, or coarse food for a shorter time. The lack of chips or obvious scrapes on the tooth suggest the former to me, but that’s speculation.

I was unaware of entelodont discoveries in Georgia, so geographically this is a significant discovery. As others have said, the tooth lacks enough diagnostic traits to identify it beyond the family level (Entelodontidae), but if it is in fact from Oligocene sediments, Archaeotherium is a reasonable assignment.

By the way, Achaenodon has four well-defined cusps and a strong posterior shelf. I do not think the tooth looks like Achaenodon.

Scott E. Foss, PhD

Regional Paleontologist

BLM Utah State Office

PO Box 45155

Salt Lake City, UT 84105

I’m grateful to Dr. Foss and Ms. Wolf for their assistance. With the comment from Dr. Foss about being unaware of Georgia’s entelodonts and Dr. MacFadden’s comment that this was a potentially interesting find for Georgia I thought I should try to have something published in the scientific literature.

Bearing in mind that I’m an amateur paleontologist, not a professional researcher, I assembled a short piece including both of the above emails and submitted it to the Georgia Journal of Science, a publication for the Georgia Academy of Sciences, of which I was a member at the time.

2/Dec/2012

Thomas,

Hello.

I admire your efforts, but the Georgia Journal of Science publishes original, professional research.

Thanks,

John V. Aliff, Ph.D.

Professor of Biology, Georgia Perimeter College

Editor, Georgia Journal of Science

An attempt to have something published in Southeastern Geology, published by Duke University’s Geology Department (now Earth and Ocean Sciences) earned a reply from the Editor-in-Chief that he would forward my proposal to the Editor, but there was only silence after that.

It can be very difficult for amateurs to get into professional publications.

In 2014 I submitted images of the tooth on Facebook’s; The Fossil Forum where I am a member. Richard S. White, one of the Fossil Forum’s administrators, became curious over my find and with his advice I contacted Dr. Richard C. Hulbert at the Florida Museum of Natural History and Dr. Hulbert agreed to review the tooth. As of this writing (Nov. 2014) Dr. Hulbert has the partial tooth and I’d prefer it remain in Georgia; I’ll likely donate it permanently to the Florida Museum of Natural History as they have shown interest in it. There, it will be available to future researchers.

I’m standing happily on my entelodont identification while urging others to be aware and watch for entelodont fossils; if the Oligocene Epoch Archaeotherium could be confirmed in Georgia it would be a scientifically important find. This single, partial tooth just isn’t enough material for such a claim.