|

|

|

20G; Diamond Back Terrapins

Article by Thomas Thurman

Malaclemys terrapin

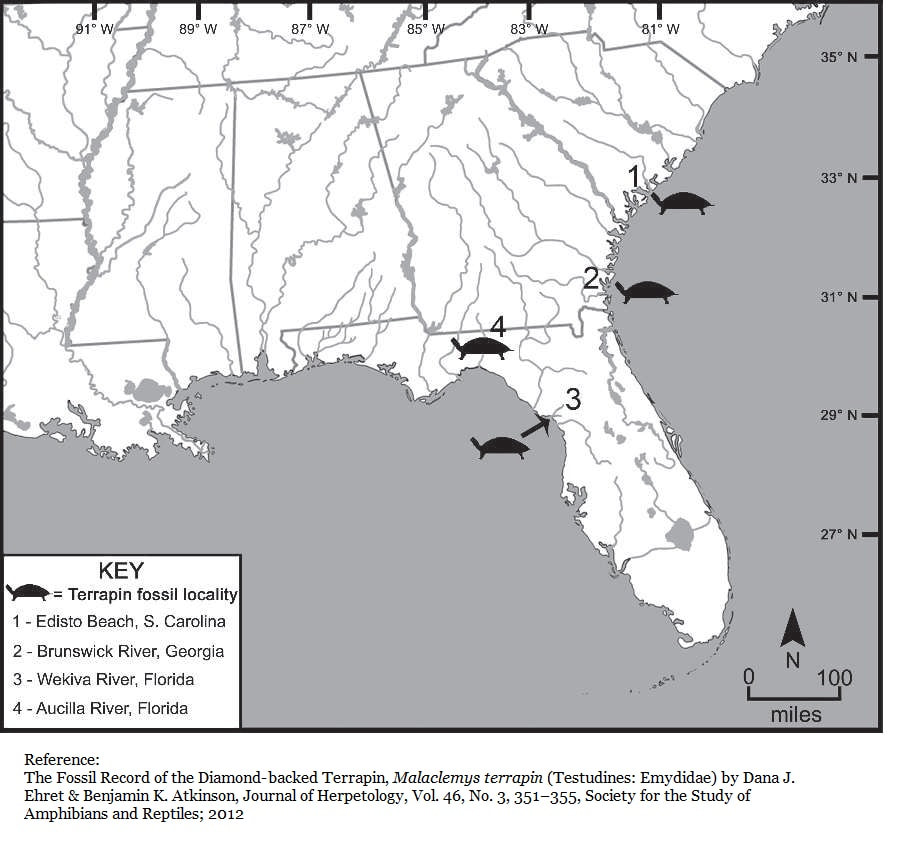

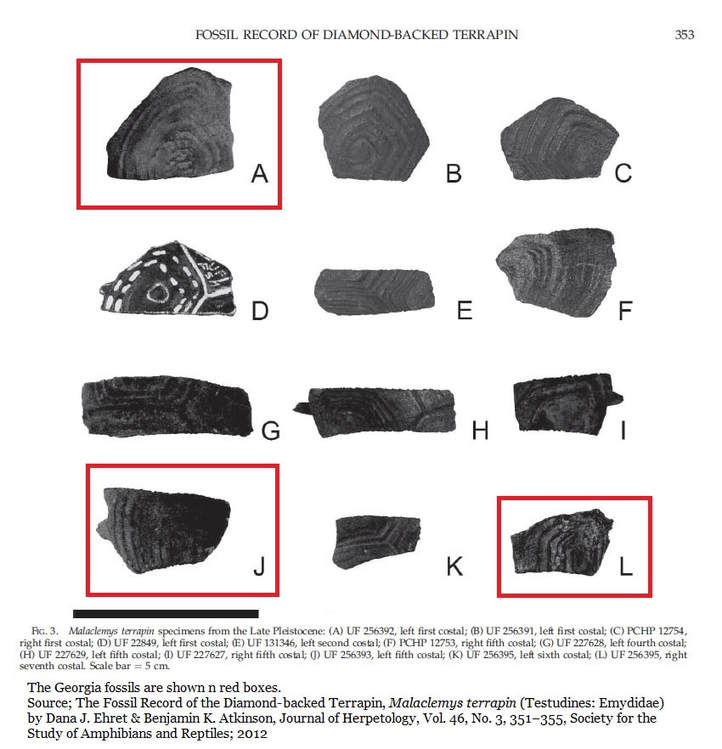

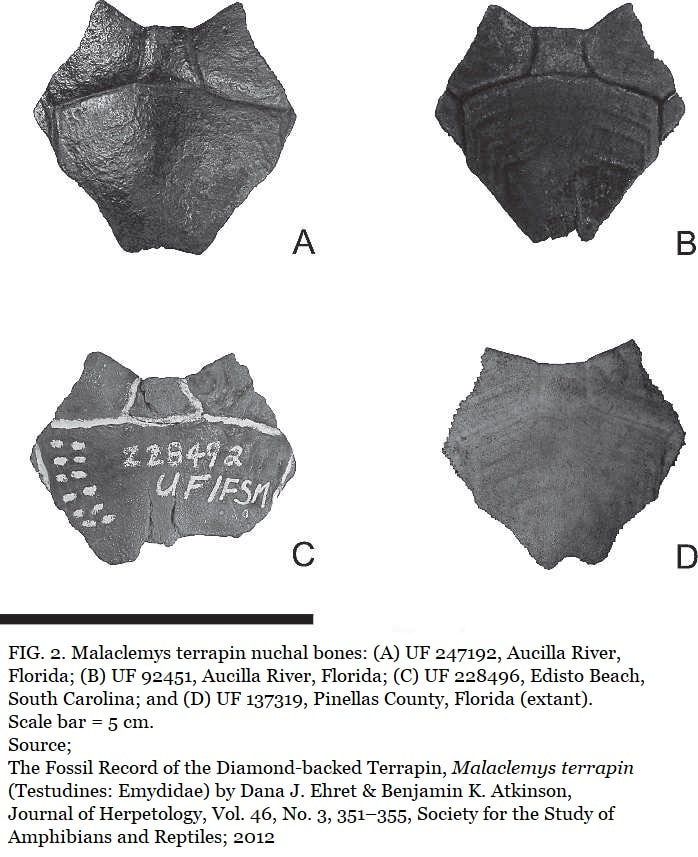

In 2012 Dana Ehret and Benjamin Atkinson reported Late Pleistocene diamond back terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) from locations in Georgia, South Carolina & Florida in the Journal of Herpetology.

Prior to this report the fossil record for the terrapin is scant; two carapace fragments from South Carolina reported in 1979, they’re included on a 2006 faunal list from Aucilla River of Florida, and a carapace and post-cranial elements were reported from Bermuda in 2008.

In 2012 Dana Ehret and Benjamin Atkinson reported Late Pleistocene diamond back terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) from locations in Georgia, South Carolina & Florida in the Journal of Herpetology.

Prior to this report the fossil record for the terrapin is scant; two carapace fragments from South Carolina reported in 1979, they’re included on a 2006 faunal list from Aucilla River of Florida, and a carapace and post-cranial elements were reported from Bermuda in 2008.

Terrapin, Turtle or Tortoise?

So what’s the difference between a terrapin, turtle and tortoise?

All three closely related reptiles belong to the order; Testudines.

Lets do tortoises first:

So what’s the difference between a terrapin, turtle and tortoise?

All three closely related reptiles belong to the order; Testudines.

Lets do tortoises first:

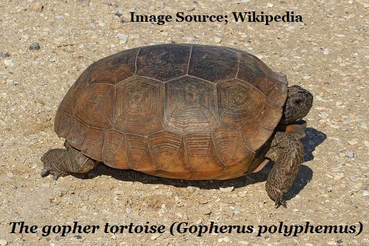

Tortoise

A tortoise is a land animal, they don’t swim, some live in deserts far from water. They’re typically heavy bodied. Trunk-like legs and elephantine feet, especially the rear feet. The front feet are often adapted toward burrowing. With very few exceptions, tortoises are herbivores. Georgia’s best known tortoise is the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) who carapace (shell) can get to about a foot long and a food high, weigh around 9 pounds and frequently lives to 40 years. Captive individuals are documented to 70+ years old.

A tortoise is a land animal, they don’t swim, some live in deserts far from water. They’re typically heavy bodied. Trunk-like legs and elephantine feet, especially the rear feet. The front feet are often adapted toward burrowing. With very few exceptions, tortoises are herbivores. Georgia’s best known tortoise is the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) who carapace (shell) can get to about a foot long and a food high, weigh around 9 pounds and frequently lives to 40 years. Captive individuals are documented to 70+ years old.

Turtle

A turtle loves water; it can be salt or fresh water. Many, like sea turtles, spend their whole lives in water, only coming ashore to lay eggs. They are frequently predators. The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) often lays her eggs on Georgia beaches. Georgia freshwaters host many turtles; the alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), Florida softshell turtle (Apalone ferox), painted turtles (Chrysemys picta), River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) and several others.

A turtle loves water; it can be salt or fresh water. Many, like sea turtles, spend their whole lives in water, only coming ashore to lay eggs. They are frequently predators. The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) often lays her eggs on Georgia beaches. Georgia freshwaters host many turtles; the alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), Florida softshell turtle (Apalone ferox), painted turtles (Chrysemys picta), River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) and several others.

Terrapins

A terrapin is usually found in brackish waters like marshes and are typically edible. The diamond back terrapin prefers coastal, salt water marshes. The term “terrapin” isn’t a taxonomic term, it isn’t used to scientifically describe a group of closely related animals. Terrapin is more of an Eastern & Southeastern term used to describe certain species.

A terrapin is usually found in brackish waters like marshes and are typically edible. The diamond back terrapin prefers coastal, salt water marshes. The term “terrapin” isn’t a taxonomic term, it isn’t used to scientifically describe a group of closely related animals. Terrapin is more of an Eastern & Southeastern term used to describe certain species.

Modern Diamond Back Terrapins.

The diamond back terrapin Malaclemys terrapin is an extant (modern) species living happily from Cape Cod to Texas along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast. The genus is specifically adapted to salt water marshes, estuaries, tidal creeks, and mangroves. Females at 7.5” long tend to be larger than males at 5.1” long. Diamond back terrapins have an uncertain future. Here in Georgia they’re considered a “Species of Concern” mostly from human consumption.

Wikipedia lists its status as:

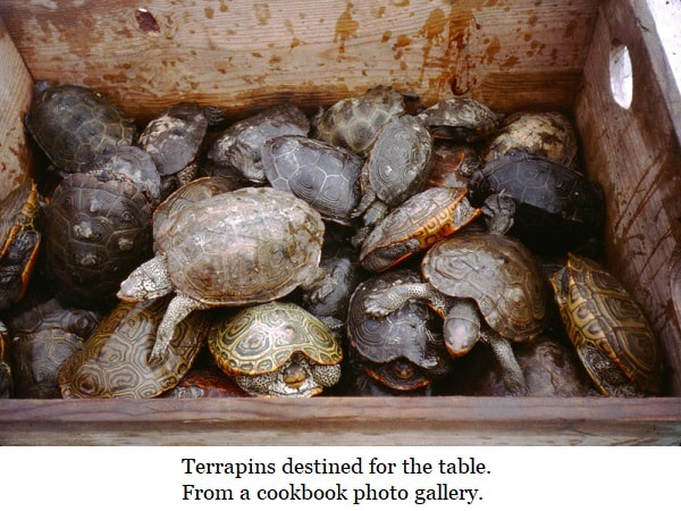

In the 1900s the species was once considered a delicacy to eat and was hunted almost to extinction. The numbers also decreased due to the development of coastal areas and, more recently, wounds from the propellers on motorboats. Another common cause of death is the trapping of the turtles under crabbing and lobster nets. Due to this, it is listed as an endangered species in Rhode Island, is considered a threatened species in Massachusetts and is considered a "species of concern" in Georgia, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. However, it holds no federal conservation status.

Wikipedia records how we nearly ate the animal into extinction:

Diamondback terrapins were heavily harvested for food in colonial America and probably before that by Native Americans. Terrapins were so abundant and easily obtained that slaves and even the Continental Army ate large numbers of them. By 1917, terrapins had become a fashionable delicacy and sold for as much as $5 each (roughly $106.00 each today). Vast numbers of terrapins were harvested from marshes and marketed in cities. By the early 1900s populations in the northern part of the range were severely depleted and the southern part was greatly reduced as well. As early as 1902 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (which later became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) recognized that terrapin populations were declining and started building large research facilities, centered at the Beaufort, North Carolina Fisheries Laboratory, to investigate methods for captive breeding terrapins for food. People tried (unsuccessfully) to establish them in many other locations, including San Francisco.

The diamond back terrapin Malaclemys terrapin is an extant (modern) species living happily from Cape Cod to Texas along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast. The genus is specifically adapted to salt water marshes, estuaries, tidal creeks, and mangroves. Females at 7.5” long tend to be larger than males at 5.1” long. Diamond back terrapins have an uncertain future. Here in Georgia they’re considered a “Species of Concern” mostly from human consumption.

Wikipedia lists its status as:

In the 1900s the species was once considered a delicacy to eat and was hunted almost to extinction. The numbers also decreased due to the development of coastal areas and, more recently, wounds from the propellers on motorboats. Another common cause of death is the trapping of the turtles under crabbing and lobster nets. Due to this, it is listed as an endangered species in Rhode Island, is considered a threatened species in Massachusetts and is considered a "species of concern" in Georgia, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. However, it holds no federal conservation status.

Wikipedia records how we nearly ate the animal into extinction:

Diamondback terrapins were heavily harvested for food in colonial America and probably before that by Native Americans. Terrapins were so abundant and easily obtained that slaves and even the Continental Army ate large numbers of them. By 1917, terrapins had become a fashionable delicacy and sold for as much as $5 each (roughly $106.00 each today). Vast numbers of terrapins were harvested from marshes and marketed in cities. By the early 1900s populations in the northern part of the range were severely depleted and the southern part was greatly reduced as well. As early as 1902 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (which later became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) recognized that terrapin populations were declining and started building large research facilities, centered at the Beaufort, North Carolina Fisheries Laboratory, to investigate methods for captive breeding terrapins for food. People tried (unsuccessfully) to establish them in many other locations, including San Francisco.

The Fossils

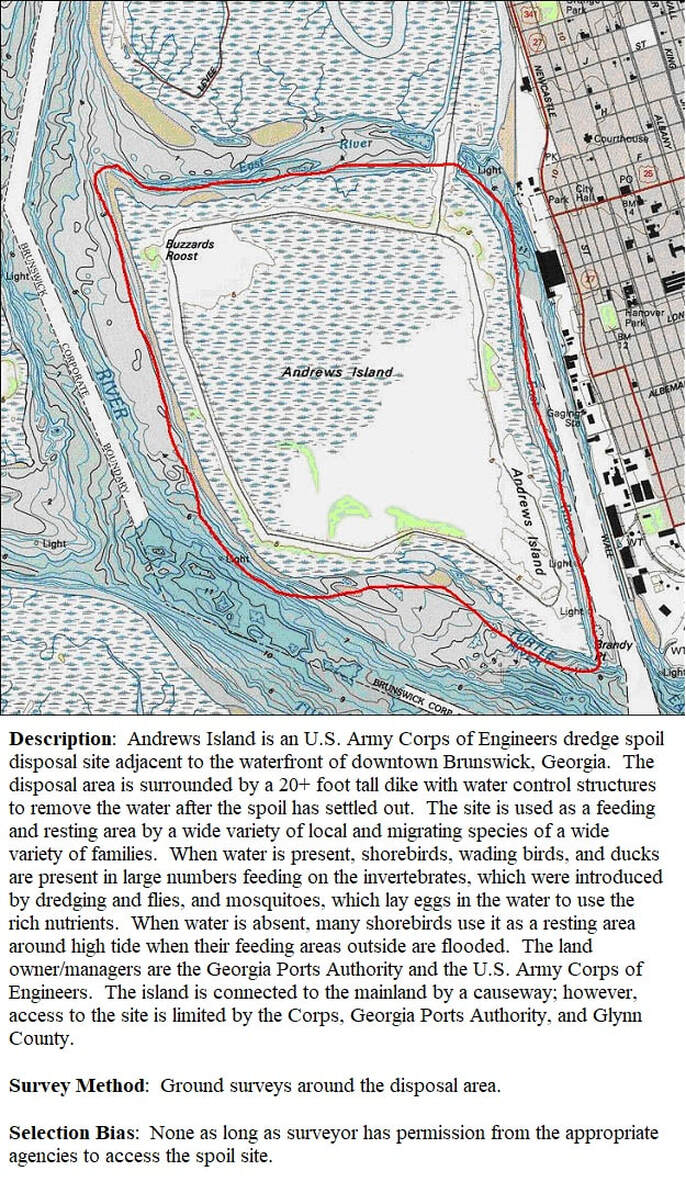

The Georgia Diamond Back terrapin fossils were recovered from dredge spoil piles on Andrews Island along the South Brunswick River in Brunswick, Glynn County, Georgia.

Dredge spoil piles are common along our rivers near the coast. Basically, this means that they were scooped from the river bed during dredging operations to deepen the river and then dumped on islands.

Fossils from dredge operations are nearly impossible to date in any way except comparison to existing material. Typically fossils from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene are found mixed together due to repeated sea level change and erosion

The Georgia Diamond Back terrapin fossils were recovered from dredge spoil piles on Andrews Island along the South Brunswick River in Brunswick, Glynn County, Georgia.

Dredge spoil piles are common along our rivers near the coast. Basically, this means that they were scooped from the river bed during dredging operations to deepen the river and then dumped on islands.

Fossils from dredge operations are nearly impossible to date in any way except comparison to existing material. Typically fossils from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene are found mixed together due to repeated sea level change and erosion

Originally the fossils existed in distinct beds, probably not far away. But they were eroded out and eventually washed into the river. The river-bed sediments were further mixed artificially when dredge buckets scooped them from the river and dumped them into dredge piles.

Hank Josey, a frequent contributor to this website, has a great deal of experience with dredge spoil fossils from the Savannah River, further north, where the same conditions exist. You can see his article at “Public Fossil Locations, Field Report on the Paleontology of the Lower Savannah River” linked here.

www.georgiasfossils.com/updated-islands-of-the-savannah-river.html

Hank Josey, a frequent contributor to this website, has a great deal of experience with dredge spoil fossils from the Savannah River, further north, where the same conditions exist. You can see his article at “Public Fossil Locations, Field Report on the Paleontology of the Lower Savannah River” linked here.

www.georgiasfossils.com/updated-islands-of-the-savannah-river.html

Three carapace fragments were recovered from Andrews Island and later compared to fossils held in collections.

The author’s report;

The fossil record for the genus Malaclemys has been increased substantially by the addition of these newly described materials. These records provide evidence that terrapins were established in the Atlantic coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia and in the Gulf coast of Florida by the Late Pleistocene.

The South Brunswick River locality in Georgia has provided the majority of new specimens and should be targeted for future collecting.

The lack of an ancestral Malaclemys at the present time does not allow us to infer the geographic origins of the taxon. However, based on its current distribution and the size and morphology of the fossils, it appears that Malaclemys terrapin evolved and dispersed along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts prior to the Late Pleistocene.

These specimens provide evidence that terrapins had been established in the Atlantic coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia, and in the Gulf coast of Florida, by the Late Pleistocene. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of Malaclemys fossils, we cannot ascertain if the genus originated along the Gulf or the Atlantic coastline.

Previous morphological studies indicate close affinities between Malaclemys and Graptemys, suggesting a close taxonomic relationship and evolutionary history between the genera (McDowell, 1964; Wood, 1977; Dobie, 1981). Wiens et al. (2010) supported a sister taxon relationship using both molecular and nuclear DNA analyses. Unfortunately, fossil records for both genera are limited, confined to the Late Pleistocene, and are not yet helpful when considering their evolutionary origins (Dobie

and Jackson, 1979; Ehret and Bourque, 2011).

The general lack of fossil material for Malaclemys to date is likely the result of misidentification (or nonidentification), inadequate collecting in areas where specimens may be found, and the fragile nature of the material. Furthermore, ecological restriction of Diamond backed Terrapins to coastal salt marshes, mangroves, and estuaries limits the potential for fossilization.

This restriction is further compounded by changes in sea level through time.

During times of lower Pleistocene sea level stands, the littoral

zone was as far as 100 m off of the present day shoreline, leaving potential fossil sites offshore today (Webb, 1990). In contrast, during times of higher Pleistocene sea level stands, this zone was pushed inland, leaving potential sites onshore. Future research on fossil Malaclemys should target deposits that cover these past ecosystem localities.

The author’s report;

The fossil record for the genus Malaclemys has been increased substantially by the addition of these newly described materials. These records provide evidence that terrapins were established in the Atlantic coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia and in the Gulf coast of Florida by the Late Pleistocene.

The South Brunswick River locality in Georgia has provided the majority of new specimens and should be targeted for future collecting.

The lack of an ancestral Malaclemys at the present time does not allow us to infer the geographic origins of the taxon. However, based on its current distribution and the size and morphology of the fossils, it appears that Malaclemys terrapin evolved and dispersed along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts prior to the Late Pleistocene.

These specimens provide evidence that terrapins had been established in the Atlantic coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia, and in the Gulf coast of Florida, by the Late Pleistocene. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of Malaclemys fossils, we cannot ascertain if the genus originated along the Gulf or the Atlantic coastline.

Previous morphological studies indicate close affinities between Malaclemys and Graptemys, suggesting a close taxonomic relationship and evolutionary history between the genera (McDowell, 1964; Wood, 1977; Dobie, 1981). Wiens et al. (2010) supported a sister taxon relationship using both molecular and nuclear DNA analyses. Unfortunately, fossil records for both genera are limited, confined to the Late Pleistocene, and are not yet helpful when considering their evolutionary origins (Dobie

and Jackson, 1979; Ehret and Bourque, 2011).

The general lack of fossil material for Malaclemys to date is likely the result of misidentification (or nonidentification), inadequate collecting in areas where specimens may be found, and the fragile nature of the material. Furthermore, ecological restriction of Diamond backed Terrapins to coastal salt marshes, mangroves, and estuaries limits the potential for fossilization.

This restriction is further compounded by changes in sea level through time.

During times of lower Pleistocene sea level stands, the littoral

zone was as far as 100 m off of the present day shoreline, leaving potential fossil sites offshore today (Webb, 1990). In contrast, during times of higher Pleistocene sea level stands, this zone was pushed inland, leaving potential sites onshore. Future research on fossil Malaclemys should target deposits that cover these past ecosystem localities.

Be aware, collecting fossils from dredge piles requires permission!

Andrew Island description from;

Birding Georgia Guide Book

by Giff Beaton (Falcon Guides)

The dredge spoil-site itself is off-limits, but the causeway to Andrews Island is good for waders and shorebirds and can easily be accessed by car. This site is very close to both Jekyll Island and St. Simons Island and can be combined with either or both of them.

Caution: This is the most mosquito-and biting fly–infested spot on the Georgia coast, and it can be quite warm here, so take both the repellent of your choice and water. Key birds: American Avocet, night-herons, salt marsh sparrows, waders, shorebirds.

Andrew Island description from;

Birding Georgia Guide Book

by Giff Beaton (Falcon Guides)

The dredge spoil-site itself is off-limits, but the causeway to Andrews Island is good for waders and shorebirds and can easily be accessed by car. This site is very close to both Jekyll Island and St. Simons Island and can be combined with either or both of them.

Caution: This is the most mosquito-and biting fly–infested spot on the Georgia coast, and it can be quite warm here, so take both the repellent of your choice and water. Key birds: American Avocet, night-herons, salt marsh sparrows, waders, shorebirds.

Reference:

The Fossil Record of the Diamond-backed Terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin (Testudines: Emydidae) by Dana J. Ehret & Benjamin K. Atkinson, Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 46, No. 3, 351–355, Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles; 2012

The Fossil Record of the Diamond-backed Terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin (Testudines: Emydidae) by Dana J. Ehret & Benjamin K. Atkinson, Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 46, No. 3, 351–355, Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles; 2012