20I; Pleistocene Vertebrate Fossils

On

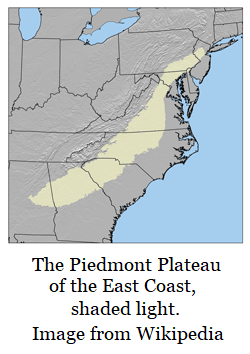

Georgia’s Piedmont

By Thomas Thurman

Created 08.Nov.2020

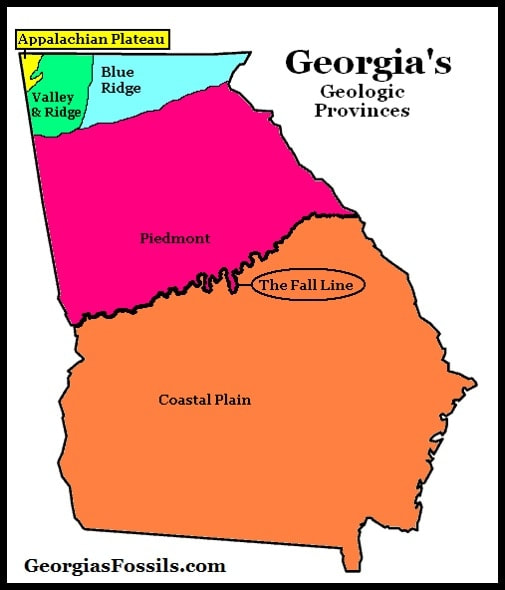

Tradition wisdom says there are no fossils on Georgia's Piedmont Plateau. But there are.

In several ways the short 1974 paper by Michael Voorhies on Piedmont Plateau fossils from Wilkes County is one of Georgia’s most important paleontological reports. Not only does it show conclusively that Pleistocene fossils occur on the Peidmont, it also creates questions about Georgia’s climate during major glacial events.

When it was published very few Pleistocene fossils had yet been reported from Georgia. Today we’re aware of a whole Pleistocene menagerie. (See Section 20B of this website).

Fossils on the Piedmont… that means most any Georgian may well live near fossiliferous deposits.

In several ways the short 1974 paper by Michael Voorhies on Piedmont Plateau fossils from Wilkes County is one of Georgia’s most important paleontological reports. Not only does it show conclusively that Pleistocene fossils occur on the Peidmont, it also creates questions about Georgia’s climate during major glacial events.

When it was published very few Pleistocene fossils had yet been reported from Georgia. Today we’re aware of a whole Pleistocene menagerie. (See Section 20B of this website).

Fossils on the Piedmont… that means most any Georgian may well live near fossiliferous deposits.

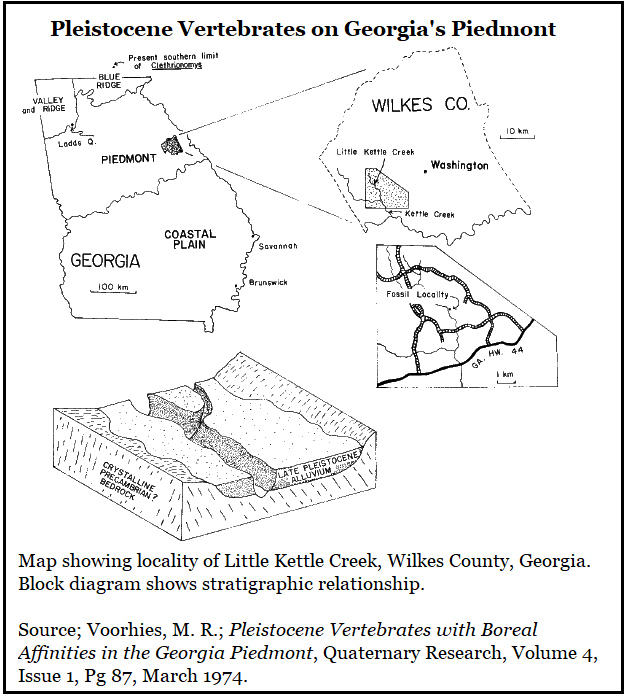

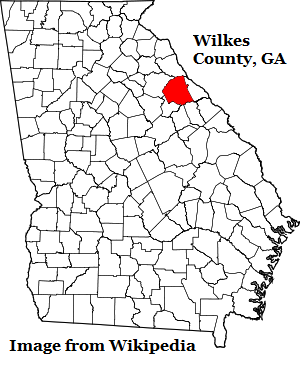

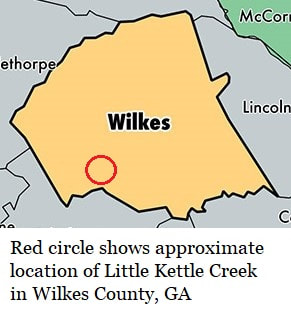

Voorhies paper is entitled Pleistocene Vertebrates with Boreal Affinities in the Georgia Piedmont and was published in March 1974 by Quaternary Research. It describes fossils found in the sediments of Little Kettle Creek in Wilkes county, fossil which seemed to be boreal (northern) species including a mammoth tooth, which he thought might have been a woolly mammoth tooth.

Voorhies; 1974

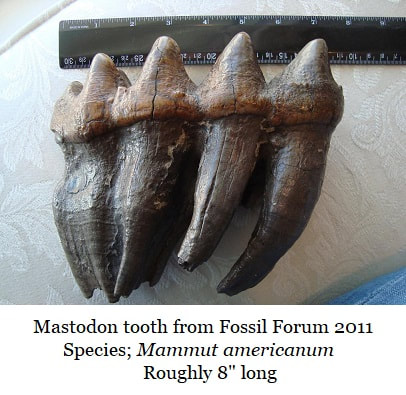

“In April 1971, Mr. Tony Tucker found a portion of a mastodon tooth in the bed of Little Kettle Creek, approximately 10km (6.2 miles) southwest of the town of Washington in Wilkes County, Georgia.” (1, pg.85)

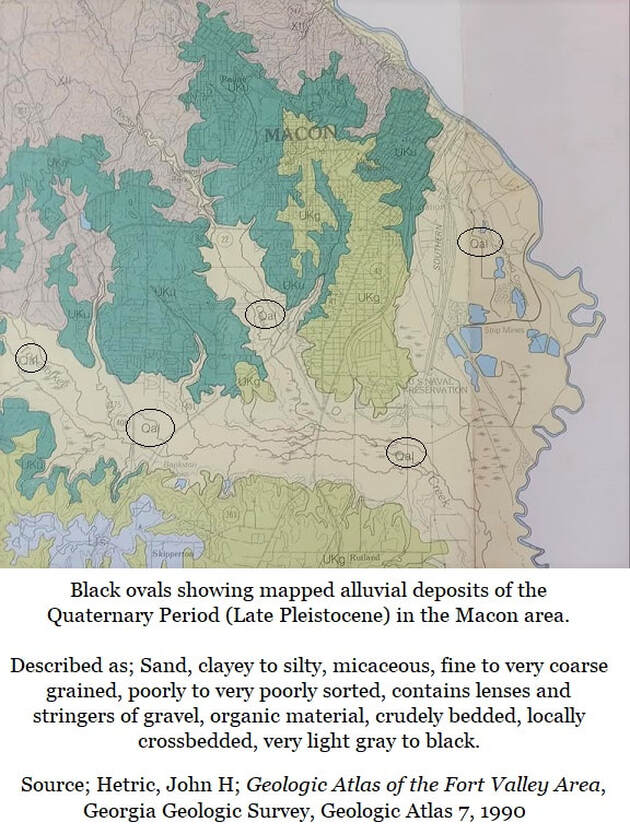

This is an alluvial deposit, sediments deposited by a river or creek. In many cases, during the Pleistocene there were major and repetitive flooding events of rivers and creeks which left behind sand beds and terrace deposits. In the last quarter of a million years there have been at least 3 sea level maximums which saw sea levels 60+ meters (200ft) above modern levels. Paul Huddlestun reported in a phone conversation that in the last 100,000 years coastlines rose to what is now Hazelhurst, GA.

“In April 1971, Mr. Tony Tucker found a portion of a mastodon tooth in the bed of Little Kettle Creek, approximately 10km (6.2 miles) southwest of the town of Washington in Wilkes County, Georgia.” (1, pg.85)

This is an alluvial deposit, sediments deposited by a river or creek. In many cases, during the Pleistocene there were major and repetitive flooding events of rivers and creeks which left behind sand beds and terrace deposits. In the last quarter of a million years there have been at least 3 sea level maximums which saw sea levels 60+ meters (200ft) above modern levels. Paul Huddlestun reported in a phone conversation that in the last 100,000 years coastlines rose to what is now Hazelhurst, GA.

The Surprise of Piedmont Fossils

I’ve personally told people that there are no fossils on Georgia’s Piedmont Plateau. Clearly, I was wrong.

Returning to his 1974 paper; Mr. Alexander Wright of the US Soil Conservation Service alerted Voorhies to the discovery of a mastodon tooth on the Piedmont in Wilkes County, GA. To quote the literature; “As no Pleistocene fossils of known stratigraphic provenance had been described from the Piedmont of Georgia, or adjacent states, it was obvious that a thorough search of the area should be made for additional material.”

Thankfully, the landowner, Mr. Hubert Tucker, was friendly to science and allowed Voorhies, the UGA students under his supervision and Alexander Wright access to his property for a proper and thorough search. Over several visits, and depending mostly on screening, a collection of vertebrate fossils was gathered.

NEVER COLLECT FOSSILS ANYWHERE WITHOUT LANDOWNER PERMISSION!

I’ve personally told people that there are no fossils on Georgia’s Piedmont Plateau. Clearly, I was wrong.

Returning to his 1974 paper; Mr. Alexander Wright of the US Soil Conservation Service alerted Voorhies to the discovery of a mastodon tooth on the Piedmont in Wilkes County, GA. To quote the literature; “As no Pleistocene fossils of known stratigraphic provenance had been described from the Piedmont of Georgia, or adjacent states, it was obvious that a thorough search of the area should be made for additional material.”

Thankfully, the landowner, Mr. Hubert Tucker, was friendly to science and allowed Voorhies, the UGA students under his supervision and Alexander Wright access to his property for a proper and thorough search. Over several visits, and depending mostly on screening, a collection of vertebrate fossils was gathered.

NEVER COLLECT FOSSILS ANYWHERE WITHOUT LANDOWNER PERMISSION!

No pollen was recovered, nor was there sufficient organic material for radio carbon dating techniques of the mid 1970s, but the population revealed, though limited, led Voorhies to conclude that the sediments represented a significantly colder climate that today’s and that these animals lived during the Rancholabrean Stage of the North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA); this dates from 240,000 years ago to 11,000 years ago.

It would seem highly likely that most creeks & rivers across the Piedmont Plateau could also be potentially productive Pleistocene fossil sites. There’s no doubt that the rivers and creeks of Georgia’s Coastal Plain generally flow across Pleistocene age alluvial deposits.

It would seem highly likely that most creeks & rivers across the Piedmont Plateau could also be potentially productive Pleistocene fossil sites. There’s no doubt that the rivers and creeks of Georgia’s Coastal Plain generally flow across Pleistocene age alluvial deposits.

The Little Kettle Creek Local Fauna

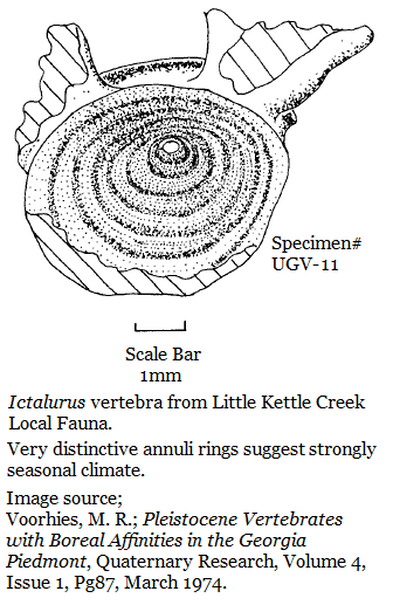

Catfish

Genus Ictalurus

Catfish, genus includes modern channel catfish and blue catfish.

A small catfish is represented by isolated pectoral spines and vertebrae (specimen UGV-11) which compare favorably to the genus Ictalurus but the remains are too fragmentary for positive identification. The vertebrae shows well defined annuli growth rings which suggest distinct, perhaps fairly dramatic climate shifts. Voorhies cites research which seems to show that cold weather retards fish growth and warm weather accelerates growth, and that the growth rings, the annuli rings, record these rates of growth. Well defined rings suggested to Voorhies widely shifting climate conditions.

Genus Ictalurus

Catfish, genus includes modern channel catfish and blue catfish.

A small catfish is represented by isolated pectoral spines and vertebrae (specimen UGV-11) which compare favorably to the genus Ictalurus but the remains are too fragmentary for positive identification. The vertebrae shows well defined annuli growth rings which suggest distinct, perhaps fairly dramatic climate shifts. Voorhies cites research which seems to show that cold weather retards fish growth and warm weather accelerates growth, and that the growth rings, the annuli rings, record these rates of growth. Well defined rings suggested to Voorhies widely shifting climate conditions.

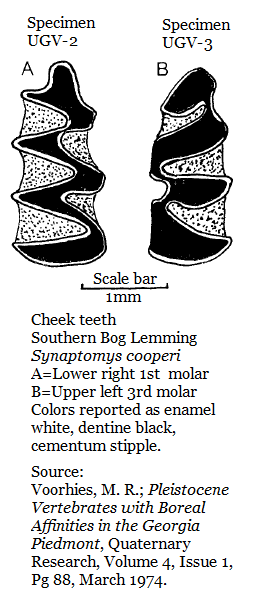

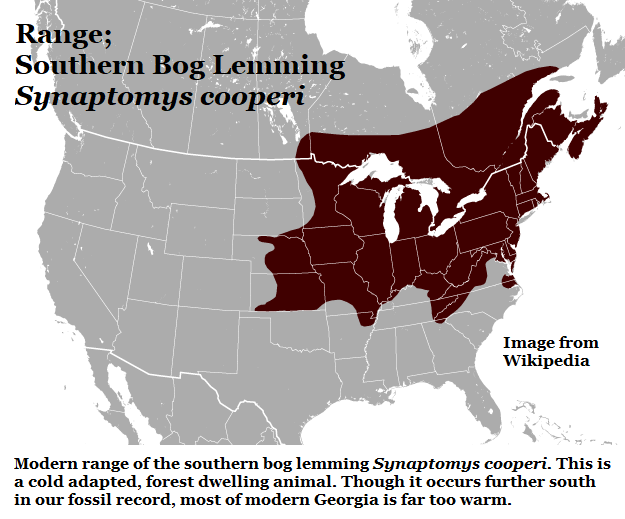

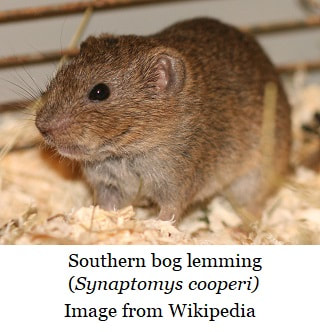

Lemming

Southern Bog Lemming

Species; Synaptomys cooperi

Two well preserved cheek teeth of the southern bog lemming.

(Specimens UGV-2 & UGV-3.)

From Wikipedia; “Southern bog lemmings are found in deciduous and mixed coniferous–deciduous forests. The grassy openings and edges of these forests, especially where sedges, ferns, and shrubs grow and when the soil is loose and crumbly, are habitats the bog lemming prefers. It also inhabits wetter and drier sites when meadow voles are scarce or absent. The southern bog lemming creates a maze of interconnecting tunnels and runways and builds nests from plant fibers. Summer nests are on the surface of the ground or in a clump of sedges or grasses, but winter nests are usually underground in an enlarged tunnel. Southern bog lemmings are just over 5” (13cm) long plus a short tail and weigh in at 1.2oz (35g).

Southern Bog Lemming

Species; Synaptomys cooperi

Two well preserved cheek teeth of the southern bog lemming.

(Specimens UGV-2 & UGV-3.)

From Wikipedia; “Southern bog lemmings are found in deciduous and mixed coniferous–deciduous forests. The grassy openings and edges of these forests, especially where sedges, ferns, and shrubs grow and when the soil is loose and crumbly, are habitats the bog lemming prefers. It also inhabits wetter and drier sites when meadow voles are scarce or absent. The southern bog lemming creates a maze of interconnecting tunnels and runways and builds nests from plant fibers. Summer nests are on the surface of the ground or in a clump of sedges or grasses, but winter nests are usually underground in an enlarged tunnel. Southern bog lemmings are just over 5” (13cm) long plus a short tail and weigh in at 1.2oz (35g).

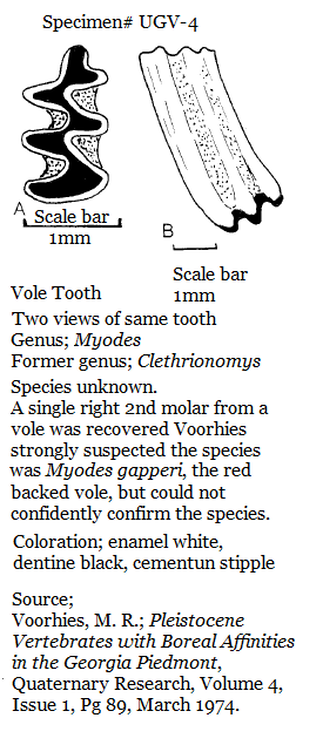

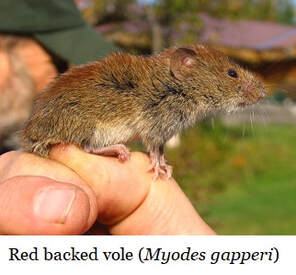

Vole

Genus; Myodes

(Formerly; Clethrionomys)

(Specimen UGV-4)

Species unknown but Voorhies strongly suspected it was a red backed vole (Myodes gapperi). Wikipedia reports; “Red-backed voles inhabit northern forests, tundra and bogs. They feed on shrubs, berries and roots. Most species have reddish brown fur on their back. They have small eyes and ears.” Voorhies notes that the species has been shown to occur in extreme north Georgia at the highest elevations, like the lemming, but not on the Piedmont. In 1974 these Wilkes County fossils were the southernmost report for the genus Myodes.

Genus; Myodes

(Formerly; Clethrionomys)

(Specimen UGV-4)

Species unknown but Voorhies strongly suspected it was a red backed vole (Myodes gapperi). Wikipedia reports; “Red-backed voles inhabit northern forests, tundra and bogs. They feed on shrubs, berries and roots. Most species have reddish brown fur on their back. They have small eyes and ears.” Voorhies notes that the species has been shown to occur in extreme north Georgia at the highest elevations, like the lemming, but not on the Piedmont. In 1974 these Wilkes County fossils were the southernmost report for the genus Myodes.

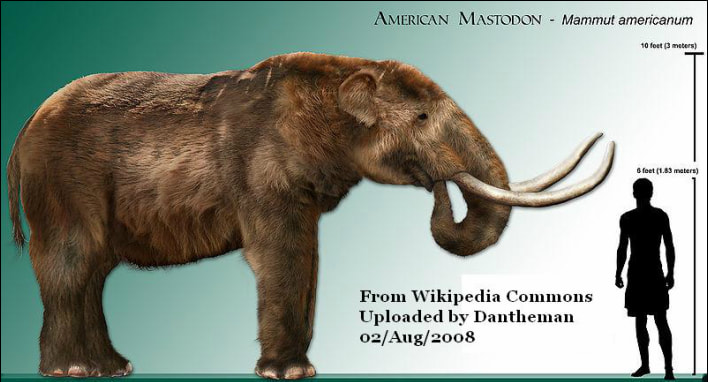

American Mastodon

Species; Mammut americanum

The front half (anterior) of a lower left molar (Specimen# UGV-1) and the rear (posterior) of an upper molar (as of 1974 this was still in the possession of Mr. Tony Tucker, Washington, GA) were collected from the stream bed. Both were little worn and Voorhies thought they were possibly from the same individual. Wikipedia states; “Mastodons lived in herds and were predominantly forest-dwelling animals that lived on a mixed diet obtained by browsing and grazing, somewhat similar to their distant relatives, modern elephants, but probably with greater emphasis on browsing.”

Species; Mammut americanum

The front half (anterior) of a lower left molar (Specimen# UGV-1) and the rear (posterior) of an upper molar (as of 1974 this was still in the possession of Mr. Tony Tucker, Washington, GA) were collected from the stream bed. Both were little worn and Voorhies thought they were possibly from the same individual. Wikipedia states; “Mastodons lived in herds and were predominantly forest-dwelling animals that lived on a mixed diet obtained by browsing and grazing, somewhat similar to their distant relatives, modern elephants, but probably with greater emphasis on browsing.”

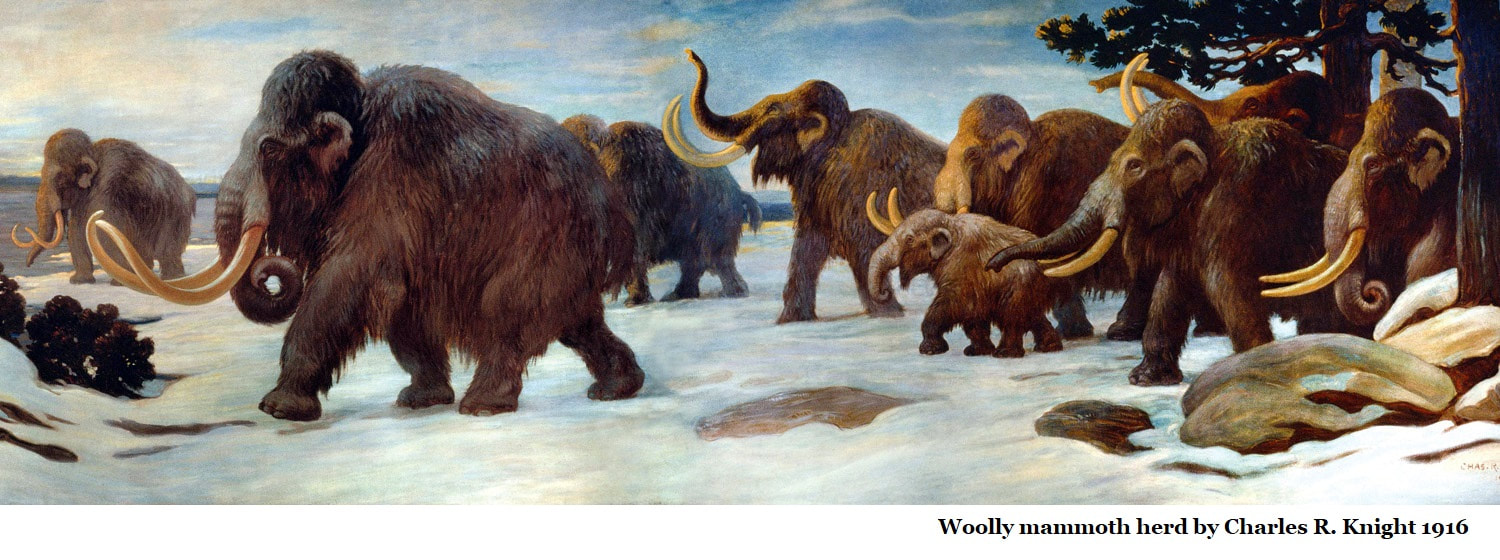

Mammoth

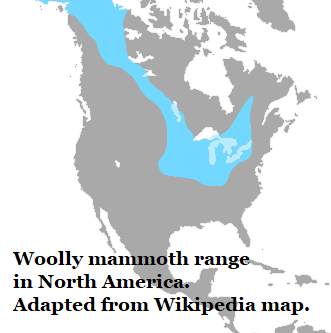

Possible Woolly Mammoth

Species; Mammuthus primigenius (?)

A partial right upper molar (Specimen# UGV-5) from a mammoth was collected from the same lens of sediments which produced the small vertebrates. Voorhies acknowledged that species identification from a damaged, isolated mammoth teeth is notoriously difficult. And that because of breakage he could not determine the maximum length or width of the molar. He did confirm that the tooth was a molar, not a premolar.

It got interesting when he turned to identifying the species. In 1969 E. Aguirre published a research paper in Science entitled Evolutionary History of the Elephant which Voorhies was aware of, Aguirre reported that the enamel of wooly mammoth teeth was thinner that that of other mammoths.

"The thickness of the enamel in the Little Kettle Creek specimen (measured by the technique of Aguirre 1969) is 1.6 & the number of enamel plates per 100mm of occlusal surface is 10. In both these features the specimen falls within the range of Mammuthus primigenius." (Voorhies,1974, pg.89)

Sadly, these fossils seem to be missing so the tooth cannot be reviewed. Though it cannot be shown now, this would be the only known report of a woolly mammoth in Georgia.

The woolly mammoth was about the same size as a modern African elephant, where the Columbian mammoth was significantly larger. As its name suggests the woolly mammoth was covered with fur, possessing an outer coat of long guard hairs and an undercoat of short hair. It was cold adapted with small ears and a short tail to minimize heat loss. It had long curved tusks and four molars which were replaced six times through the animal’s life.

According to Wikipedia, the southernmost occurrence of the woolly mammoth is in Shandong Province of China which has a latitude of 33°24’. Little Kettle Creek in Wilkes County, GA is a bit further north at 33°40’.

Possible Woolly Mammoth

Species; Mammuthus primigenius (?)

A partial right upper molar (Specimen# UGV-5) from a mammoth was collected from the same lens of sediments which produced the small vertebrates. Voorhies acknowledged that species identification from a damaged, isolated mammoth teeth is notoriously difficult. And that because of breakage he could not determine the maximum length or width of the molar. He did confirm that the tooth was a molar, not a premolar.

It got interesting when he turned to identifying the species. In 1969 E. Aguirre published a research paper in Science entitled Evolutionary History of the Elephant which Voorhies was aware of, Aguirre reported that the enamel of wooly mammoth teeth was thinner that that of other mammoths.

"The thickness of the enamel in the Little Kettle Creek specimen (measured by the technique of Aguirre 1969) is 1.6 & the number of enamel plates per 100mm of occlusal surface is 10. In both these features the specimen falls within the range of Mammuthus primigenius." (Voorhies,1974, pg.89)

Sadly, these fossils seem to be missing so the tooth cannot be reviewed. Though it cannot be shown now, this would be the only known report of a woolly mammoth in Georgia.

The woolly mammoth was about the same size as a modern African elephant, where the Columbian mammoth was significantly larger. As its name suggests the woolly mammoth was covered with fur, possessing an outer coat of long guard hairs and an undercoat of short hair. It was cold adapted with small ears and a short tail to minimize heat loss. It had long curved tusks and four molars which were replaced six times through the animal’s life.

According to Wikipedia, the southernmost occurrence of the woolly mammoth is in Shandong Province of China which has a latitude of 33°24’. Little Kettle Creek in Wilkes County, GA is a bit further north at 33°40’.

White tailed deer

Genus: Odocoileus (?) virginianus

An upper left premolar (specimen# UGV-6) and a “damaged fused” left metatarsals III & IV (specimen# UGV-7) which Voorhies reported as comparing closely with modern white tailed deer, but he must have had doubts and deferred on a positive ID.

Genus: Odocoileus (?) virginianus

An upper left premolar (specimen# UGV-6) and a “damaged fused” left metatarsals III & IV (specimen# UGV-7) which Voorhies reported as comparing closely with modern white tailed deer, but he must have had doubts and deferred on a positive ID.

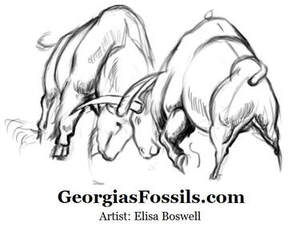

Bison

A right lower first molar (specimen UGV-10), an intermediate phalanx (specimen UGV-8) and the proximal end of fused right metacarpals III & IV (specimen# UGV-9) represent a large bovid. The molar strongly suggested a member of the genus Bison.

A right lower first molar (specimen UGV-10), an intermediate phalanx (specimen UGV-8) and the proximal end of fused right metacarpals III & IV (specimen# UGV-9) represent a large bovid. The molar strongly suggested a member of the genus Bison.

Paleoclimatology

Glaciers grow and coasts retreat, glacier melt and costs advance.

A glaciation, is a cooling event. Temperatures fall, glaciers grow, advance and sea levels fall because of so much water is trapped as ice.

An interglacial is a warming event, glaciers melt, retreat and sea levels rise.

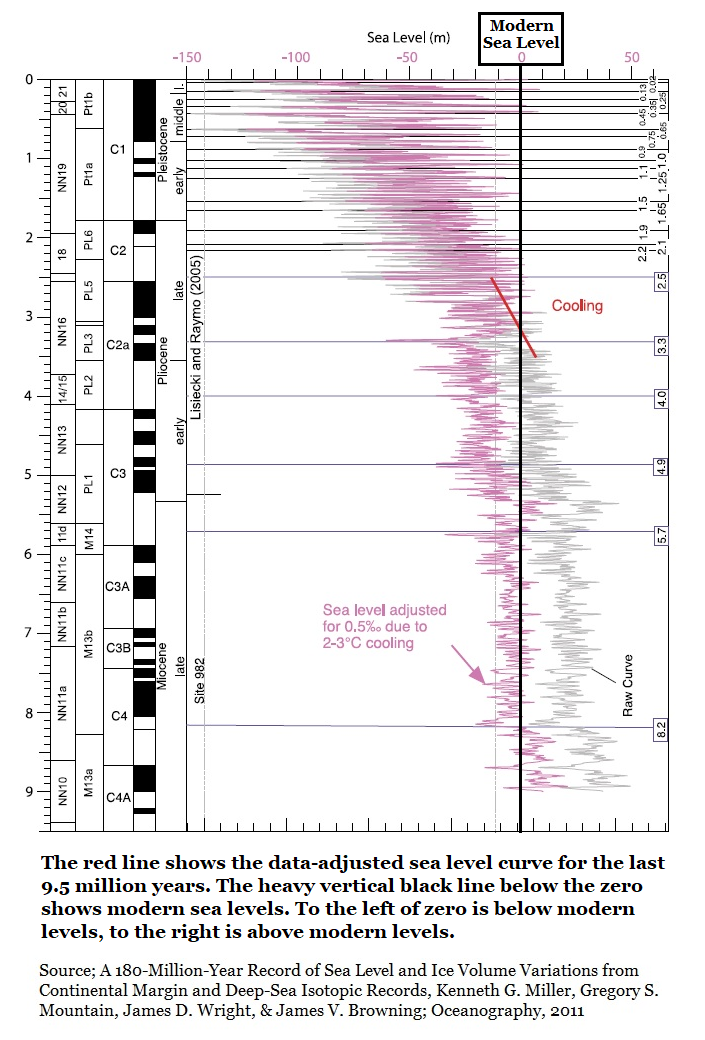

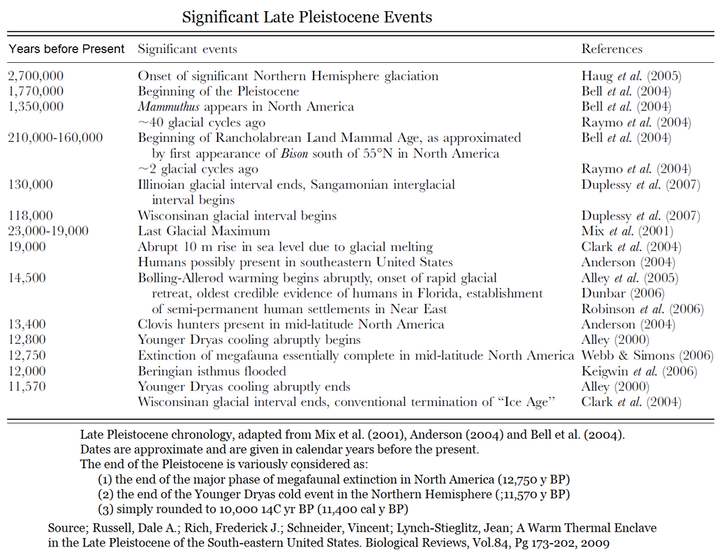

For roughly the last 10 million years, a cycle of frequent glaciation and interglacial events has occurred across the globe. This cycle is caused by many things, but it is unusual in Earth’s long history. Without it, humans wouldn’t exist.

When Voorhies published this report in 1974 the highly cyclical nature of Pleistocene glaciation and interglacial events was poorly understood. Understanding is better today, but still far from perfect.

Yet in the 1960s & 1970s researchers were finding boreal (northern) species in the Southeast. This is part of the reason why Sam Pickering (State Geologists from 1972-1978) initiated a large scale research project through the maddingly complex sediments Georgia Coastal Plain.

Glaciers grow and coasts retreat, glacier melt and costs advance.

A glaciation, is a cooling event. Temperatures fall, glaciers grow, advance and sea levels fall because of so much water is trapped as ice.

An interglacial is a warming event, glaciers melt, retreat and sea levels rise.

For roughly the last 10 million years, a cycle of frequent glaciation and interglacial events has occurred across the globe. This cycle is caused by many things, but it is unusual in Earth’s long history. Without it, humans wouldn’t exist.

When Voorhies published this report in 1974 the highly cyclical nature of Pleistocene glaciation and interglacial events was poorly understood. Understanding is better today, but still far from perfect.

Yet in the 1960s & 1970s researchers were finding boreal (northern) species in the Southeast. This is part of the reason why Sam Pickering (State Geologists from 1972-1978) initiated a large scale research project through the maddingly complex sediments Georgia Coastal Plain.

Voorhies was aware of 1969 research by J.E. Guilday over mammals from Tennessee caves and Pleistocene pollen described in 1964 by D.R. Whitehead from southeastern North Carolina. Voorhies cites 1962 research by D.R. Whitehead & E.S. Barghoorn where pollen from boreal vegetation (spruce, fir & hemlock) was recovered in western North & South Carolina.

He further observes that in 1970 W. A. Watts completed a study of Pleistocene pollen from two ponds in the Appalachian Valley & Ridge province in northwestern Georgia. In 1974 this pollen was Carbon 14 dated to between 13,500 to 20,000 years old. Watts concluded, in 1970, that “a displacement of some 700 miles would be required to bring the same species back to Georgia.”

In light of all of this, Voorhies concluded that these reports “leave no doubt that boreal faunal and floral elements penetrated far into the southeastern states during Wisconsin glacial maxima.” (1, pg.90)

He further observes that in 1970 W. A. Watts completed a study of Pleistocene pollen from two ponds in the Appalachian Valley & Ridge province in northwestern Georgia. In 1974 this pollen was Carbon 14 dated to between 13,500 to 20,000 years old. Watts concluded, in 1970, that “a displacement of some 700 miles would be required to bring the same species back to Georgia.”

In light of all of this, Voorhies concluded that these reports “leave no doubt that boreal faunal and floral elements penetrated far into the southeastern states during Wisconsin glacial maxima.” (1, pg.90)

A Warm Thermal Enclave

I mentioned that a great deal of work has been done in Southeastern Pleistocene vertebrate fauna since 1974. This came to a bit of a head in a 2009 with the publication of the paper A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. (3) The lead author was Dale Russell of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences but Fredrick Rich of Georgia Southern was one of the co-authors.

Rich was unaware of Voorhies Piedmont paper until 2020. The 1974 paper is rather obscure these days. For the record, in a 19/Nov/2020 phone conversation Voorhies admitted he was unaware of the Thermal Enclave paper.

The Thermal Enclave paper first attracted my attention as it has extensive lists of Southeastern, Pleistocene vertebrate fossils (& some flora), the paper also notes which states fossils were reported from. It lists Florida, Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Georgia. It breaks Georgia into Northwest Georgia & Coastal Georgia.

I mentioned that a great deal of work has been done in Southeastern Pleistocene vertebrate fauna since 1974. This came to a bit of a head in a 2009 with the publication of the paper A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. (3) The lead author was Dale Russell of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences but Fredrick Rich of Georgia Southern was one of the co-authors.

Rich was unaware of Voorhies Piedmont paper until 2020. The 1974 paper is rather obscure these days. For the record, in a 19/Nov/2020 phone conversation Voorhies admitted he was unaware of the Thermal Enclave paper.

The Thermal Enclave paper first attracted my attention as it has extensive lists of Southeastern, Pleistocene vertebrate fossils (& some flora), the paper also notes which states fossils were reported from. It lists Florida, Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Georgia. It breaks Georgia into Northwest Georgia & Coastal Georgia.

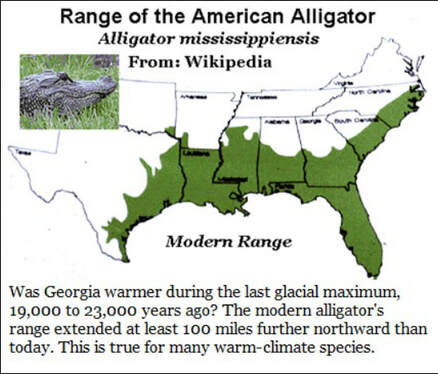

The authors proposed that the Southeast represented a warm oasis in an otherwise cold North America. Their theory is based on the observation than caves of NW Georgia and sites in Virginia both produced reports of fossils for the American alligator, Alligator mississippiensis (3,pg.179) and the extinct giant land tortoise Hesperotestudo crassiscutata (3,pg.178) reptiles who are not cold adapted. (see section 20F of tis website)

Today, the range of the American alligator roughly follows Georgia’s Fall Line.

The theory is that heat is trapped from the warm Gulf Stream current to power the Thermal Enclave.

Undoubtedly warm climate species occur in Georgia during the glacial maximums.

But reindeer (caribou) Rangifer tarandus (3,pg.183)also occur in Georgia’s Pleistocene fossil record, caribou are an artic species.

Today, the range of the American alligator roughly follows Georgia’s Fall Line.

The theory is that heat is trapped from the warm Gulf Stream current to power the Thermal Enclave.

Undoubtedly warm climate species occur in Georgia during the glacial maximums.

But reindeer (caribou) Rangifer tarandus (3,pg.183)also occur in Georgia’s Pleistocene fossil record, caribou are an artic species.

Dating the Thermal Enclave

Carbon 14 Dating of collection sites. (3,pg177)

Location Years before Present (“Present” as 1950)

North-west Georgia:

Ladds Quarry 10,290 & 10,940

Kingston Saltpeter Cave 10,300

Yarbrough Cave 14,315/16,500/18,610/23,880

Coastal Georgia

Jones Girls Site 40,000 to 80,000 years

Watkins Quarry 10,000 years

Carbon 14 Dating of collection sites. (3,pg177)

Location Years before Present (“Present” as 1950)

North-west Georgia:

Ladds Quarry 10,290 & 10,940

Kingston Saltpeter Cave 10,300

Yarbrough Cave 14,315/16,500/18,610/23,880

Coastal Georgia

Jones Girls Site 40,000 to 80,000 years

Watkins Quarry 10,000 years

There is evidence to support a warm thermal enclave in the Southeast during portions of the Late Pleistocene.

There is evidence to support the presence of boreal & even artic species in Georgia during the Late Pleistocene.

When I asked Voorhies about this he pointed out that these two facts aren't contradictory, that in the last million years there have been at least nine events where sea levels rose more than 50 meters (164feet) above modern levels. There’s been maybe twenty glacial events where sea levels fell more than 100 meters (328feet).

There is evidence to support the presence of boreal & even artic species in Georgia during the Late Pleistocene.

When I asked Voorhies about this he pointed out that these two facts aren't contradictory, that in the last million years there have been at least nine events where sea levels rose more than 50 meters (164feet) above modern levels. There’s been maybe twenty glacial events where sea levels fell more than 100 meters (328feet).

Fred Rich agrees, in a 28/November/2020 email he commented comparatively on Voorhies 1974 paper and the Thermal Enclave work he'd been involved in.

Hi Thomas,

This is just a quick comment. I read the Voorhies paper, and went

over our paper concerning the Enclave. I agree with him that these interpretations do not conflict with each other. The fact that the megafauna and its associated smaller fossils came from the Piedmont is perfectly consistent with the interpretation that a Warm Enclave existed in the Coastal Plain area. The megafauna came from further north and from a higher elevation than our samples. That is consistent with what one might expect for differing faunal zones within a large geographic region.

This has been very interesting, and I thank you.

Fred

Voorhies in Georgia

In 1974 Voorhies reported that all specimens collected from Little Kettle Creek were housed in the Geology Department of the University of Georgia. (1,pg.87)

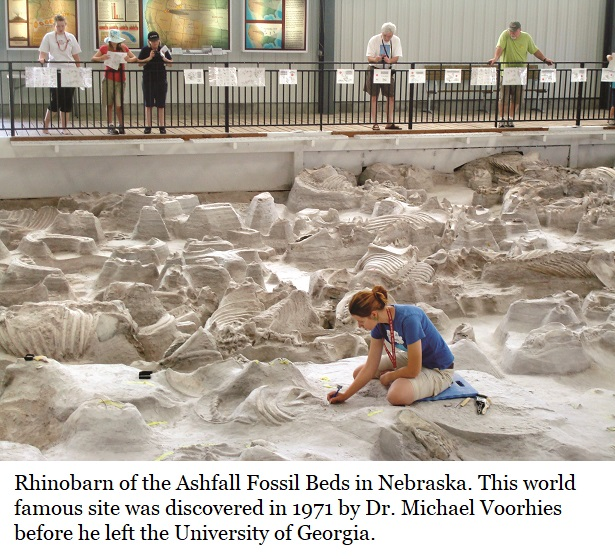

Voorhies grew up in Nebraska. He came to Georgia to teach paleontology at UGA. There he met his wife Jane and proved quickly himself a superb vertebrate paleontologist. Unfortunately for Georgia, a Nebraska job offer tempted him to return home. There Voorhies found international fame by discovering the Nebraska Ashfall Beds (4) in 1971, an amazing snapshot of Nebraska wildlife 10 to 12 million years ago.

Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park (unl.edu)

In 1974 Voorhies reported that all specimens collected from Little Kettle Creek were housed in the Geology Department of the University of Georgia. (1,pg.87)

Voorhies grew up in Nebraska. He came to Georgia to teach paleontology at UGA. There he met his wife Jane and proved quickly himself a superb vertebrate paleontologist. Unfortunately for Georgia, a Nebraska job offer tempted him to return home. There Voorhies found international fame by discovering the Nebraska Ashfall Beds (4) in 1971, an amazing snapshot of Nebraska wildlife 10 to 12 million years ago.

Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park (unl.edu)

A Lost Collection

Sadly, all the fossils Voorhies collected as a Professor of Paleontology at the University of Georgia, are lost. During his time at UGA in the 1970s the specimens were added to the Geology Department’s collections.

This was an exciting time when large scale, expansive geologic research was beginning to gear up in Georgia. Voorhies was right in the middle of it all. Sam Pickering, one of Georgia’s former State Geologists, credited Voorhies with naming the Clinchfield Sand in 1965. It had previously, and erroneously, been assigned with the Gosport Sand in Alabama. (2,pg.7) Though a superb scientists, Pickering always misspelled Voorhies name as “Vorhis” for unknown reasons. Sam Pickering passed in August of 2020.

In researching this article I contacted both UGA’s Geology Department and the Georgia Museum of Natural History, on the UGA campus, about the fossils Voorhies collected and housed at UGA. The below reply from Byron Freeman, Director of the Georgia Museum of Natural History.

Sadly, all the fossils Voorhies collected as a Professor of Paleontology at the University of Georgia, are lost. During his time at UGA in the 1970s the specimens were added to the Geology Department’s collections.

This was an exciting time when large scale, expansive geologic research was beginning to gear up in Georgia. Voorhies was right in the middle of it all. Sam Pickering, one of Georgia’s former State Geologists, credited Voorhies with naming the Clinchfield Sand in 1965. It had previously, and erroneously, been assigned with the Gosport Sand in Alabama. (2,pg.7) Though a superb scientists, Pickering always misspelled Voorhies name as “Vorhis” for unknown reasons. Sam Pickering passed in August of 2020.

In researching this article I contacted both UGA’s Geology Department and the Georgia Museum of Natural History, on the UGA campus, about the fossils Voorhies collected and housed at UGA. The below reply from Byron Freeman, Director of the Georgia Museum of Natural History.

18/Nov/2020

Thomas;

We have been looking for these early specimens that Michael collected and have not had much success locating them, other than the sloth that was exhibited in the Boyd Graduate Studies building, the Museum has removed this to a storage facility. I’ve not given up hope finding these fossils, however this is a long haul.

Much material from Geology was stored in the crawl space beneath the River Bend Research Labs, and a fire in this area prompted a rushed removal of many objects. I had hoped to find fossils then, however we didn’t locate any of the Voorhies specimens.

Bud Freeman

Director, Georgia Museum Natural History

Thomas;

We have been looking for these early specimens that Michael collected and have not had much success locating them, other than the sloth that was exhibited in the Boyd Graduate Studies building, the Museum has removed this to a storage facility. I’ve not given up hope finding these fossils, however this is a long haul.

Much material from Geology was stored in the crawl space beneath the River Bend Research Labs, and a fire in this area prompted a rushed removal of many objects. I had hoped to find fossils then, however we didn’t locate any of the Voorhies specimens.

Bud Freeman

Director, Georgia Museum Natural History

I’ve spoken to Dr. Voorhies a couple of times, most recently in November 2020. I was hoping he had copies of his research he might share when he learned his specimens had been lost, but that work was nearly 50 years ago and he’s been very busy since. As we talked he expressed lingering interests in Georgia. “If it hadn’t been for work in Nebraska, I could have been happy in Georgia. There’s some good paleontology to do in Georgia and I’m glad interests is being renewed.”

Voorhies made a large impact on Georgia’s Earth Science. Despite the tragedy of his lost research specimens, you can still see a scientifically important specimen he collected. This is Ziggy, the Durodon serratus, an early 35 million year old whale on permanent display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA. As told in Section 13 of this website, Ziggy was discovered in 1973 by amateur geologists Bill Christy and his son Billy. They alerted Voorhies and through UGA the fossil was recovered. At the time it was the most complete basilosaurid ever found. In time it was reconstructed and put on permanent display at the Museum of Arts & Sciences where Christy volunteered. Sadly, Bill Christy passed in October of 2010.

Voorhies made a large impact on Georgia’s Earth Science. Despite the tragedy of his lost research specimens, you can still see a scientifically important specimen he collected. This is Ziggy, the Durodon serratus, an early 35 million year old whale on permanent display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA. As told in Section 13 of this website, Ziggy was discovered in 1973 by amateur geologists Bill Christy and his son Billy. They alerted Voorhies and through UGA the fossil was recovered. At the time it was the most complete basilosaurid ever found. In time it was reconstructed and put on permanent display at the Museum of Arts & Sciences where Christy volunteered. Sadly, Bill Christy passed in October of 2010.

So Get Out There!

All of Georgia is waiting.

Wherever you are in Georgia, whichever province, have a look at the streams & rivers. If there are sand beds then there’s a good chance they’re alluvial Pleistocene deposits and might hold fossils. Get landowner permission before proceeding.

So Get Out There!

All of Georgia is waiting.

Wherever you are in Georgia, whichever province, have a look at the streams & rivers. If there are sand beds then there’s a good chance they’re alluvial Pleistocene deposits and might hold fossils. Get landowner permission before proceeding.

Thanks Ashley!

Ashley Quinn has my gratitude for locating & forwarding this 1974 paper by Voorhies. Ashley stands as Treasurer of the Paleontology Association of Georgia & Collections Manager of the William P. Wall Museum of Natural History at Georgia College in Milledgeville. She is also a highly capable vertebrate paleontologist in her own right.

Ashley Quinn has my gratitude for locating & forwarding this 1974 paper by Voorhies. Ashley stands as Treasurer of the Paleontology Association of Georgia & Collections Manager of the William P. Wall Museum of Natural History at Georgia College in Milledgeville. She is also a highly capable vertebrate paleontologist in her own right.

References

- Voorhies, M. R.; Pleistocene Vertebrates with Boreal Affinities in the Georgia Piedmont, Quaternary Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, Pg 85-93, March 1974.

- Pickering, S. M. Jr.; Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; Bulletin 81, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1970

- Russell, Dale A.; Rich, Frederick J.; Schneider, Vincent; Lynch-Stieglitz, Jean; A Warm Thermal Enclave in the Late Pleistocene of the South-eastern United States. Biological Reviews, Vol.84, Pg 173-202, 2009

- Wikipedia entry on Nebraska’s Ashfall Beds Ashfall Fossil Beds - Wikipedia

Georgia Research papers

The papers discussed here and many other over Georgia's paleontology, can be found at the Paleontology Association of Georgia (PAG) website; you'll see the Resources tab.

paleoassocga.wixsite.com