7D; Xiphactinus vetus;

The Bulldog Fish

By Thomas Thurman

Imagine an angry, 4.5 meter (15 foot), fanged tarpon. Xiphactinus vetus certainly looked like a large tarpon but they weren't closley related. They're different families, but they do resemble.

This is another large, new species from Alabama and Georgia; discovered by David R Schwimmer, J.D. Stewart & G. Dent Williams.

Xiphactinus vetus (pronounced: Zee-fact-teen-us vee-tus), was a very close relative to the animal (X. audax) from Kansas illustrated here with my daughter.

This is another large, new species from Alabama and Georgia; discovered by David R Schwimmer, J.D. Stewart & G. Dent Williams.

Xiphactinus vetus (pronounced: Zee-fact-teen-us vee-tus), was a very close relative to the animal (X. audax) from Kansas illustrated here with my daughter.

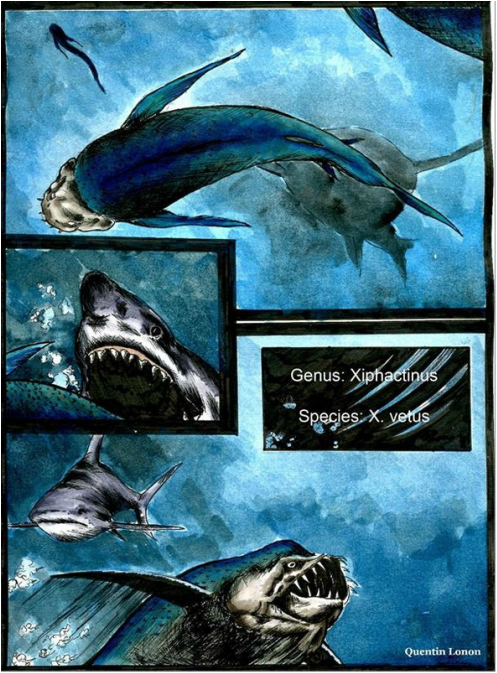

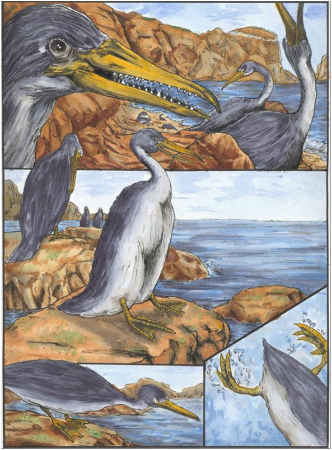

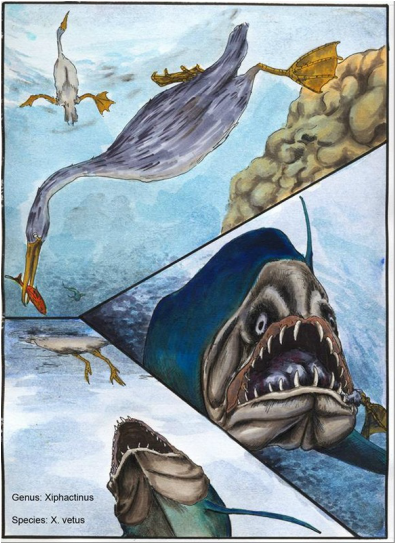

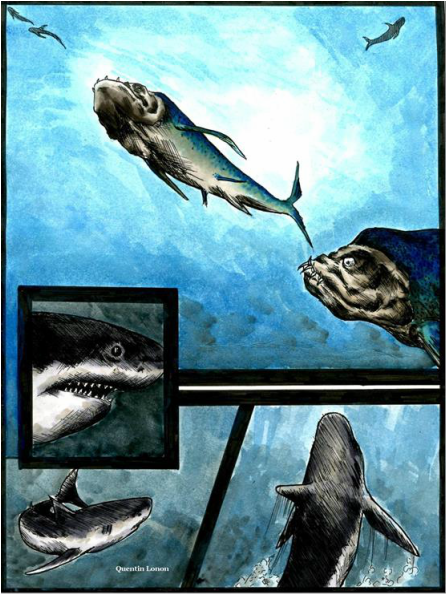

Artist Quentin Lonon created the following images of a living Xiphactinus vetus swimming in our lost Cretaceous sea. The image set begins with the bird genus Hesperornis (meaning western bird) which is unreported from the fossil record of Georgia and Alabama, but is known to occur in the Western Interior Seaway.

This was a large flightless bird but an active swimmer. Its wings had atrophied into stubs but its sideways facing feet made it a superb swimmer. It had a long beak complete with teeth.

Xiphactinus vetus is seen stalking one from beneath the waves, and taking one in a successful hunt.

There is no known reason why

Hesperornis couldn't be discovered among Georgia's Cretaceous fossils.

This was a large flightless bird but an active swimmer. Its wings had atrophied into stubs but its sideways facing feet made it a superb swimmer. It had a long beak complete with teeth.

Xiphactinus vetus is seen stalking one from beneath the waves, and taking one in a successful hunt.

There is no known reason why

Hesperornis couldn't be discovered among Georgia's Cretaceous fossils.

Perhaps the scent of blood in the water attracts the unwelcomed attention of a hungry shark.

Sharks would have been major competitors, and in the scenes Quentin created, one shark makes an unsuccessful attack on our Xiphactinus vetus. Fast as the shark may be, it wasn’t fast enough.

Xiphactinus vetus was built for great bursts of speed. It was likely much faster than most sharks.

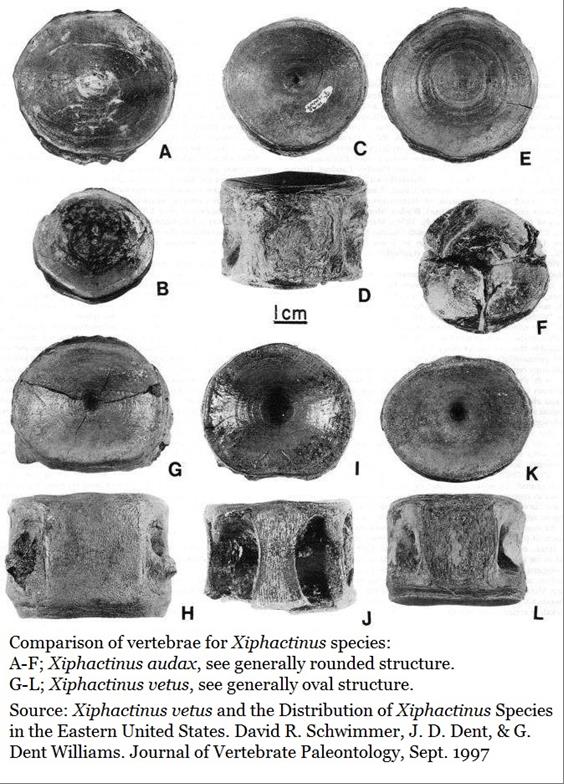

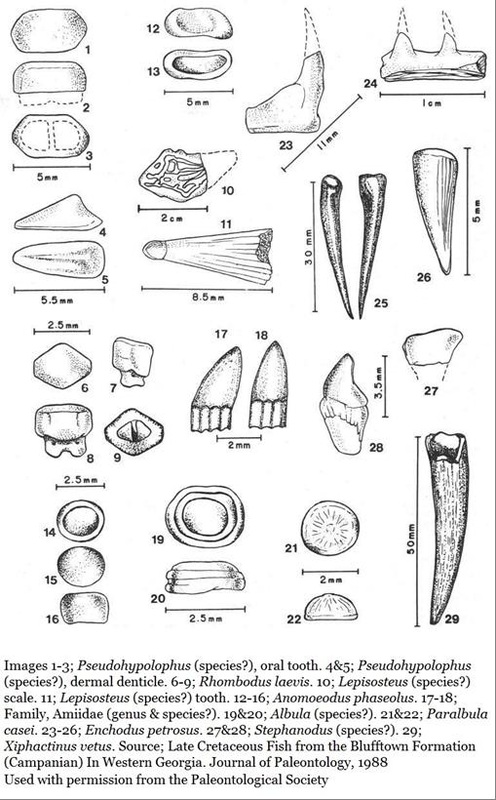

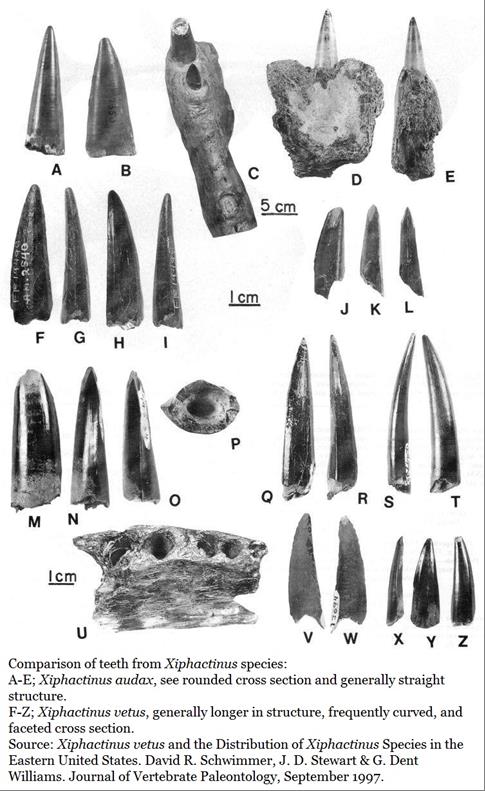

It occurs in Georgia and Alabama. It is identified as a distinct species by elongated, curved, faceted teeth and distinct vertebra which the ancestor Xiphactinus audax lacked. (See images of the fossils below.)

Judging by the size of its teeth our local species, Xiphactinus vetus, was at least as large, or larger, than Xiphactinus audax.

In life, Xiphactinus vetus would have been a formidable predator at least 4.5 meters or 15 feet long.

It would have hunted with curved teeth were meant for seizing prey.

Judging by the size of its teeth our local species, Xiphactinus vetus, was at least as large, or larger, than Xiphactinus audax.

In life, Xiphactinus vetus would have been a formidable predator at least 4.5 meters or 15 feet long.

It would have hunted with curved teeth were meant for seizing prey.

Note: In a 2/June/2013 email Dr. Schwimmer reported the following; and I quote: “Xiphactinus vetus is also known in New Jersey and North Carolina; and, there are specimens I identified a few years ago from Wyoming (published in a New Mexico Museum Bulletin).”

Judging by the fossil record, Xiphactinus vetus would have occurred in some numbers in our coastal sea.

Reference:

Xiphactinus vetus and the Distribution of Xiphactinus Species in the Eastern United States. David R. Schwimmer, J.D. Dent and G. Dent Williams Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 17, No.3, Sept. 1997. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

Judging by the fossil record, Xiphactinus vetus would have occurred in some numbers in our coastal sea.

Reference:

Xiphactinus vetus and the Distribution of Xiphactinus Species in the Eastern United States. David R. Schwimmer, J.D. Dent and G. Dent Williams Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 17, No.3, Sept. 1997. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

***

Note (15/July/2020);

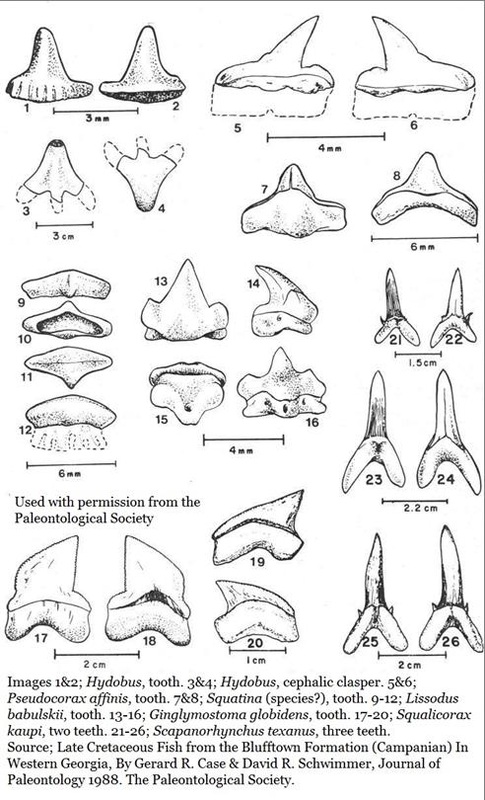

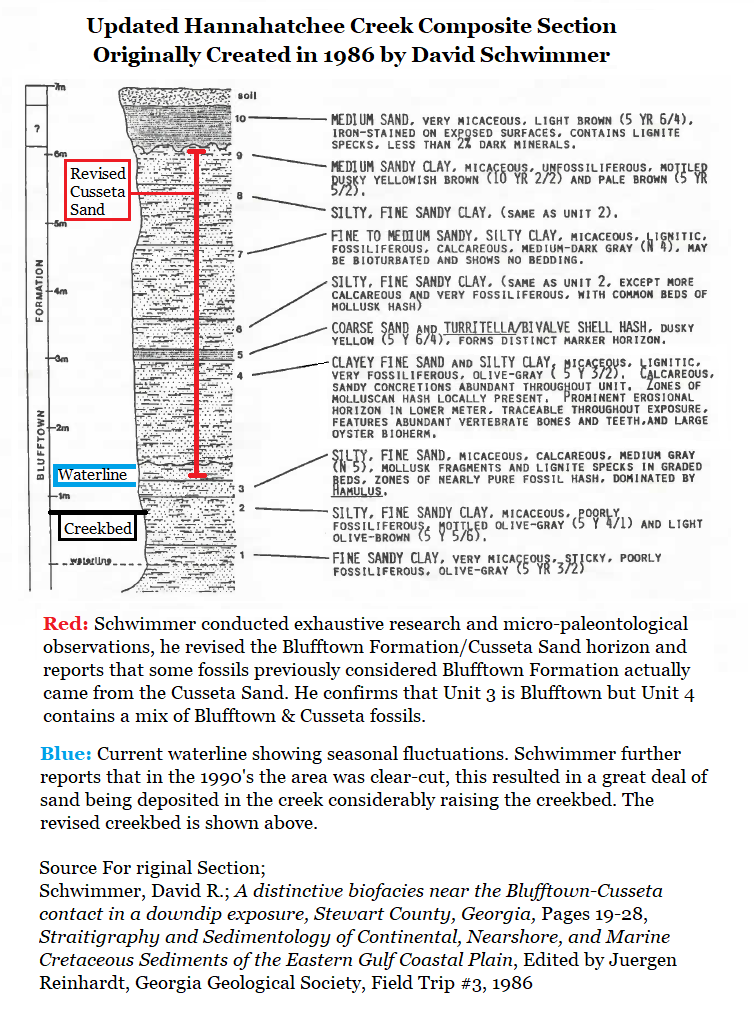

So after detailed observations in micropaleontology, over years, Schwimmer learned that some of the fossils originally attributed to the Blufftown Formation actually came from the overlying Cusseta Sand or the mixed bed between the two.

11/June/2020 Note from Schwimmer: "...many of the fossils I attributed to the Blufftown back in the 80's and early 90's, actually come from the base of the overlying Cusseta Fm. Took me a lot of observation and some microfossil work to figure that the productive bed was actually the basal Cusseta with reworked Blufftown material." (Personal Communication)

So after detailed observations in micropaleontology, over years, Schwimmer learned that some of the fossils originally attributed to the Blufftown Formation actually came from the overlying Cusseta Sand or the mixed bed between the two.

11/June/2020 Note from Schwimmer: "...many of the fossils I attributed to the Blufftown back in the 80's and early 90's, actually come from the base of the overlying Cusseta Fm. Took me a lot of observation and some microfossil work to figure that the productive bed was actually the basal Cusseta with reworked Blufftown material." (Personal Communication)