14C1:

Georgia's First Oreodont

& The Oldest One in the Southeast!

By Thomas Thurman

19/June/2022

The Amateur/Professional Relationship

& How It Shapes Our Knowledge

Of Georgia’s Natural History

Georgia's First The & Southeast Oldest Oreodont

A fossilized snout was found by an amateur a dozen years ago while shooting in one of the many abandoned Tivola Limestone quarries of Houston County. My friend did not have permission to be on the property.

Two separate institutions have identified the fossil as belonging to a member of the oreodont family.

This would not only be Georgia's first oreodont, but it would also be the oldest oreodont yet reported from the southeast; the Tivola Limestone is a Late Eocene deposit. All other southeast oreodonts are Oliogocene and Miocene, or millions of years younger.

However, since the fossil was collected illegally it'll never be properly published and officially added to Georgia's fossil record.

Names Withheld

While I'm typically careful to give people and institutions credit where credit is due, in this essay, and for everyone's protection, I will name neither people or institutions involved in this history.

Our Fossil Record

Georgia’s natural history is both deep and complex; it’s punctuated and illustrated by our diverse vertebrate and invertebrate fossil record. Yet much Georgia’s antiquity remains poorly understood as erosion and weathering have reworked so much of our landscape. Imagine a history book missing whole chapters. So clearly, the more species of any kind which can be properly identified and dated from Georgia’s fossil record, or the Southeast in general, the better our understanding.

Most Georgia amateurs lack a path towards getting scientifically important fossils published in peer-reviewed literature. This is often true for both beginners and advanced amateurs with field experience and extensive contacts.

The peer-reviewed publication of scientifically significant finds is important. There are a few professionally managed global paleontology databases. Here in the USA the best known of these is the Paleobiology Database (The Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org)) It only accepts published records from peer-reviewed journals. If a species hasn’t been published as occurring in Georgia’s record, it does not make the Paleobiology Database.

Nevertheless, such databases have become the foundation for research, locally, regionally, and globally. Once a new discovery is published and incorporated into these databases researchers around the world can weave it, like a new thread, into the tapestry of Earth’s natural history.

Peer-Review Literature & Publication

We should start by defining “peer-reviewed publication”.

In this sense, peer-reviewed publication means you create a report and send it to a geology, paleontology, or regional science journal editor. Typically, it’s a journal published by an association or society. To submit a manuscript and be considered for publication you must first become a member of that society by paying the membership fee.

Once submitted the editor reviews your report, if they find it has merit they’ll share it with at least three or four other society members with similar backgrounds and request their honest opinions. While reviewers are anonymous to the submitting author, journal editors frequently ask the author for a list of both suggested reviewers and reviewers-to-be-avoided.

We should start by defining “peer-reviewed publication”.

In this sense, peer-reviewed publication means you create a report and send it to a geology, paleontology, or regional science journal editor. Typically, it’s a journal published by an association or society. To submit a manuscript and be considered for publication you must first become a member of that society by paying the membership fee.

Once submitted the editor reviews your report, if they find it has merit they’ll share it with at least three or four other society members with similar backgrounds and request their honest opinions. While reviewers are anonymous to the submitting author, journal editors frequently ask the author for a list of both suggested reviewers and reviewers-to-be-avoided.

New Discoveries

The vast majority of new paleontological discoveries are made by amateurs they’re the ones constantly in the field. Some discoveries are accidental, found by inexperience hands which see something curious and recover it.

Others are made by advanced amateurs who’ve done their homework and understand the sediments they’re exploring; they immediately recognize the potential value of an unusual specimen.

The vast majority of new paleontological discoveries are made by amateurs they’re the ones constantly in the field. Some discoveries are accidental, found by inexperience hands which see something curious and recover it.

Others are made by advanced amateurs who’ve done their homework and understand the sediments they’re exploring; they immediately recognize the potential value of an unusual specimen.

New Reports

Meanwhile, the vast majority of a peer-reviewed reports are authored by professional or academic paleontologist and geologist. For academics, the old maxim of “publish or perish” still rings true.

This means that amateurs are almost wholly dependent on professionals to see their finds published and added to paleontology databases. So it’s no surprise that academics can be wonderfully welcoming to amateurs who bring them potentially publishable material. Some professional researchers actively maintain mutually beneficial relationships with a network of amateurs.

But such relationships can be unpredictable. While some academics are very welcoming and helpful to amateurs, others are not and operate from the perspective that amateurs have no place in scientific research.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of a peer-reviewed reports are authored by professional or academic paleontologist and geologist. For academics, the old maxim of “publish or perish” still rings true.

This means that amateurs are almost wholly dependent on professionals to see their finds published and added to paleontology databases. So it’s no surprise that academics can be wonderfully welcoming to amateurs who bring them potentially publishable material. Some professional researchers actively maintain mutually beneficial relationships with a network of amateurs.

But such relationships can be unpredictable. While some academics are very welcoming and helpful to amateurs, others are not and operate from the perspective that amateurs have no place in scientific research.

From Field to Database

Two questions arise…

This is important. If Henry the Hiker, Harry the Hunter, or Carol the Canoer, stumbles onto a fossilized jawbone (mandible) with possible scientific importance, and this happens more frequently than you’d think, what’s the likelihood of it finding publication and being added to paleontological databases?

Sadly, the chances are low, abysmally low… there are so many obstacles to overcome.

Two questions arise…

- What percentage of scientifically important amateur finds are ever seen by researchers?

- What percentage of professionally recognized, scientifically important finds are actually published?

This is important. If Henry the Hiker, Harry the Hunter, or Carol the Canoer, stumbles onto a fossilized jawbone (mandible) with possible scientific importance, and this happens more frequently than you’d think, what’s the likelihood of it finding publication and being added to paleontological databases?

Sadly, the chances are low, abysmally low… there are so many obstacles to overcome.

Amateurs can also Part of the Problem

Of course, amateurs can also part of the problem. They often shoot science in the foot because they want to protect “their spot” which probably isn’t on their property.

In some cases, these people looking to sell fossils for a profit. The author recognizes both the importance and historical significance of fossil dealers. The famous English Paleontologist Mary Anning was one of the first people ever to earn a modest living collecting and selling fossils. Historically there have been many a research papers published over fossils purchased from a dealer.

But bear in mind that money & fossils can be a troublesome mix; one needs look no further than the saga of Sue the Tyrannosaurus rex from South Dakota. (Sue (dinosaur) - Wikipedia) No doubt fossils can be valuable, otherwise museums wouldn’t be interested in them, but science is quickly trampled when fossils are measured in dollars instead of knowledge.

Of course, amateurs can also part of the problem. They often shoot science in the foot because they want to protect “their spot” which probably isn’t on their property.

In some cases, these people looking to sell fossils for a profit. The author recognizes both the importance and historical significance of fossil dealers. The famous English Paleontologist Mary Anning was one of the first people ever to earn a modest living collecting and selling fossils. Historically there have been many a research papers published over fossils purchased from a dealer.

But bear in mind that money & fossils can be a troublesome mix; one needs look no further than the saga of Sue the Tyrannosaurus rex from South Dakota. (Sue (dinosaur) - Wikipedia) No doubt fossils can be valuable, otherwise museums wouldn’t be interested in them, but science is quickly trampled when fossils are measured in dollars instead of knowledge.

In most cases collectors just want to protect their site. I get that. However, if you recover a canoe full assorted vertebrate remains but cannot properly date or identify them, they’re of no financial or scientific importance to anyone. A box full of fossils with no provenance is a just box of curious rocks.

That said. If a dealer has an unidentified fossil, or a fossil which cannot be properly dated, then the value of that fossil is dramatically diminished. If that same dealer lets someone knowledgeable assist in dating and IDing a specimen, then its value is greatly enhanced. No dealer wants a reputation of selling improperly identified specimens. No dealer wants to sell $1,000.00 fossil for $20.00 because of an error in dating or identification.

That said. If a dealer has an unidentified fossil, or a fossil which cannot be properly dated, then the value of that fossil is dramatically diminished. If that same dealer lets someone knowledgeable assist in dating and IDing a specimen, then its value is greatly enhanced. No dealer wants a reputation of selling improperly identified specimens. No dealer wants to sell $1,000.00 fossil for $20.00 because of an error in dating or identification.

Yes, science wants to know where you found your fossils, visiting the site is often the only way to properly date it. No, science isn’t going to give away your secret. Researchers have every reason to protect a site from being pillaged.

Sometimes you have to let knowledgeable people into your site to date the sediments and create a published scientific record; this advances the science and increases to value of your finds.

Remember, collect responsibly.

Sometimes you have to let knowledgeable people into your site to date the sediments and create a published scientific record; this advances the science and increases to value of your finds.

Remember, collect responsibly.

Lost Fossil

Back in 2012 I found a partial entelodont tooth in Bonaire, Houston County, Georgia. See Section 16 of this website for details. Only one other hell pig tooth had ever been reported in Georgia and that one came from Twiggs County. The Twiggs County tooth has been lost by the university caring for it and no photograph or drawing survives.

A central Georgia university ID’d my tooth as an entelodont but had zero interest in pursuing it further. This ID was later confirmed by pictures sent to western researchers. I asked another Georgia researcher to have a look and if he thought it was worth publishing, he agreed to look at it and I shipped it to him.

Back in 2012 I found a partial entelodont tooth in Bonaire, Houston County, Georgia. See Section 16 of this website for details. Only one other hell pig tooth had ever been reported in Georgia and that one came from Twiggs County. The Twiggs County tooth has been lost by the university caring for it and no photograph or drawing survives.

A central Georgia university ID’d my tooth as an entelodont but had zero interest in pursuing it further. This ID was later confirmed by pictures sent to western researchers. I asked another Georgia researcher to have a look and if he thought it was worth publishing, he agreed to look at it and I shipped it to him.

Upon review he decided this fossil was just too far beyond of his normal work and suggested a Florida researcher. I contacted Florida and was encouraged to send the fossil on for review. The Georgia researcher volunteered to ship the fossil directly to Florida. I agreed thinking that the less it was handled the better.

After hearing nothing a couple of months I contacted the Florida researcher only to learn the partial tooth had never found him. Tracking numbers showed it had been delivered to the university, but nothing beyond that. The tooth was gone.

After hearing nothing a couple of months I contacted the Florida researcher only to learn the partial tooth had never found him. Tracking numbers showed it had been delivered to the university, but nothing beyond that. The tooth was gone.

Lost Opportunity

Why all this worry about publishing finds?

Just before the first Covid lockdowns a friend showed me fossils he’d found in Houston County’s Tivola Limestone 10 or 11 years earlier. The Tivola Limestone is roughly 35 million years old and is a marine deposit set down by strong currents. (See Section 14I; Dating Late Eocene Sediments of this website for details.) The fossil came from an abandoned quarry in Houston County which hadn’t been active in 50 years or more. There are half a dozen such quarries, all are on private property.

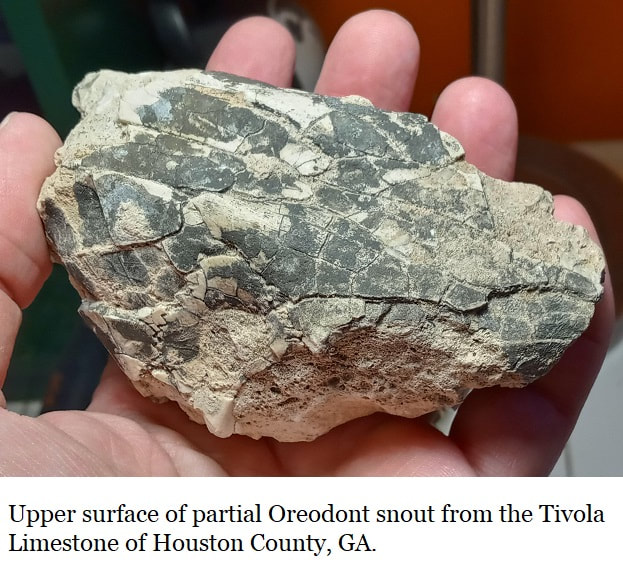

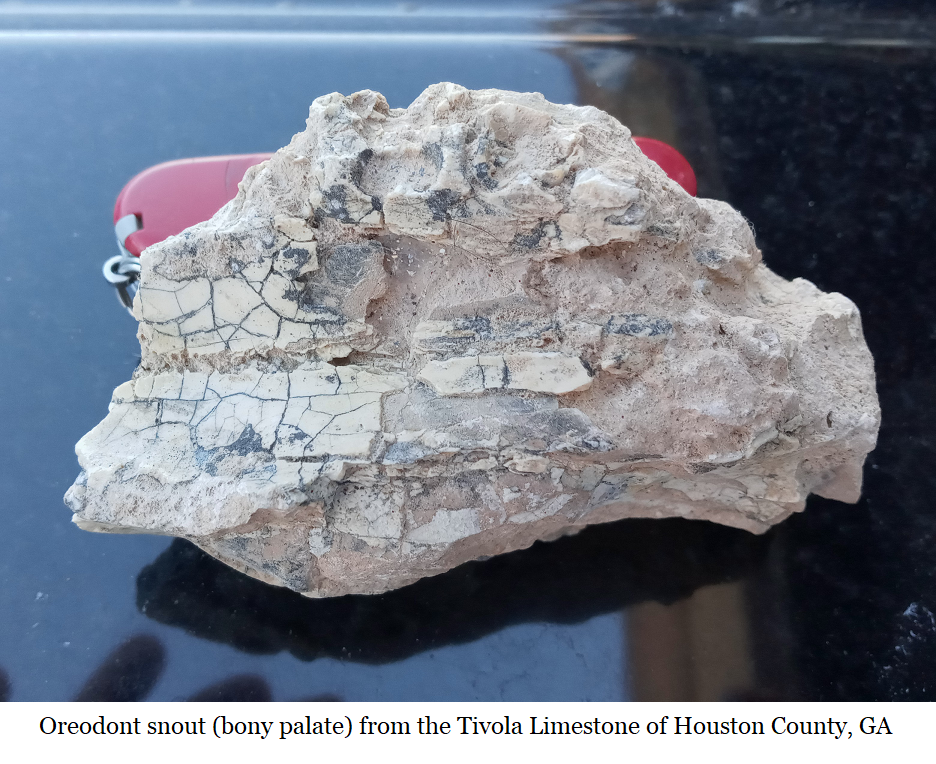

His box held a few very nice Periarchus pileusinensis sand dollars, which are common in the Tivola, a few scallops and a fist sized piece which appeared to be a partial snout from a skull.

Why all this worry about publishing finds?

Just before the first Covid lockdowns a friend showed me fossils he’d found in Houston County’s Tivola Limestone 10 or 11 years earlier. The Tivola Limestone is roughly 35 million years old and is a marine deposit set down by strong currents. (See Section 14I; Dating Late Eocene Sediments of this website for details.) The fossil came from an abandoned quarry in Houston County which hadn’t been active in 50 years or more. There are half a dozen such quarries, all are on private property.

His box held a few very nice Periarchus pileusinensis sand dollars, which are common in the Tivola, a few scallops and a fist sized piece which appeared to be a partial snout from a skull.

“It used to be larger, but pieces broke off over the years…” My friend explained.

Bony material is very rare in the Tivola Limestone. Bony material is easily destroyed by rolling along on the bottom under strong currents. The collection location would have been roughly 10 miles offshore with a water depth of probably 100ft or less, within the photic zone. (Photic Zone; zone where enough sun light penetrates the sea water for photosynthesis.)

Bony material is very rare in the Tivola Limestone. Bony material is easily destroyed by rolling along on the bottom under strong currents. The collection location would have been roughly 10 miles offshore with a water depth of probably 100ft or less, within the photic zone. (Photic Zone; zone where enough sun light penetrates the sea water for photosynthesis.)

Still, I was holding what appeared to be the underside of a snout, the bony palate that once formed the roof of an animal’s mouth. It didn’t appear to be to be a marine animal. It’s always possible that a specimen was buried quickly and was thus preserved.

I explained as much to my friend. I told him that this was potentially a significant find. That if it’s a terrestrial mammal, then those are very, very rare in the Tivola. To find out I’d need to show it to some paleontologist I know. They’d need to handle it. So I’d need to borrow the fossil for a few days.

I explained as much to my friend. I told him that this was potentially a significant find. That if it’s a terrestrial mammal, then those are very, very rare in the Tivola. To find out I’d need to show it to some paleontologist I know. They’d need to handle it. So I’d need to borrow the fossil for a few days.

I’d been down this road before.

The next day I picked the fossil up, I thanked her for her efforts and reminded her that according to the Paleobiology Database oreodonts are unreported from Georgia. So I’d have to explore other contacts about getting this fossil published.

The next day I picked the fossil up, I thanked her for her efforts and reminded her that according to the Paleobiology Database oreodonts are unreported from Georgia. So I’d have to explore other contacts about getting this fossil published.

Georgia Paleontologists

Considering how little most lifelong Georgians know about our natural history, there are a surprising number of working paleontologists in the state. Most are academics, so they’re typically interested in pursuing publication. We have an array of vertebrate paleontologist, invertebrate paleontologist, and paleobotanist. That said, they’re typically specialist, experts in some aspect of their paleontological discipline and rarely wander outside their area of expertise. Georgia lacks a general vertebrate paleontologist with a solid background in geology.

Sadly, the Georgia paleontologists with the most experience with oreodonts had just informed me that they weren’t interested, they fall into that amateurs-have-no-place-in-science category. They’re technically paleobiologist with lots of training in biology and anatomy but less training or experience in geology and stratigraphy.

We roll on, looking for those who can & will help.

Considering how little most lifelong Georgians know about our natural history, there are a surprising number of working paleontologists in the state. Most are academics, so they’re typically interested in pursuing publication. We have an array of vertebrate paleontologist, invertebrate paleontologist, and paleobotanist. That said, they’re typically specialist, experts in some aspect of their paleontological discipline and rarely wander outside their area of expertise. Georgia lacks a general vertebrate paleontologist with a solid background in geology.

Sadly, the Georgia paleontologists with the most experience with oreodonts had just informed me that they weren’t interested, they fall into that amateurs-have-no-place-in-science category. They’re technically paleobiologist with lots of training in biology and anatomy but less training or experience in geology and stratigraphy.

We roll on, looking for those who can & will help.

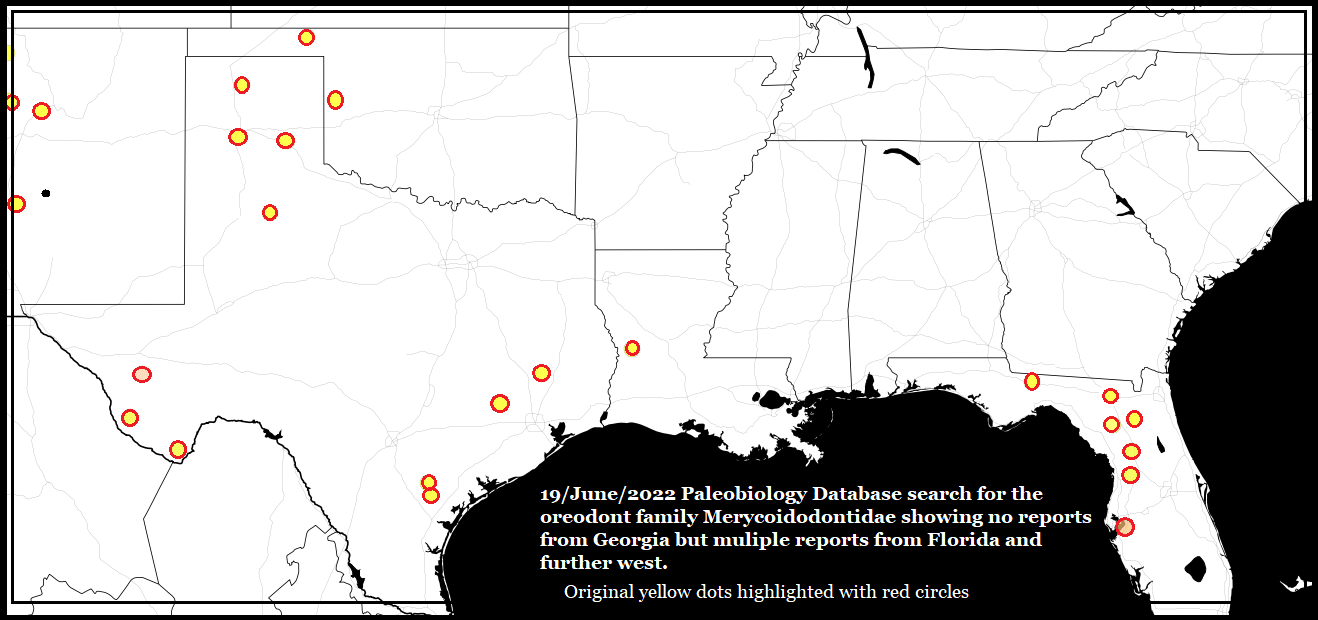

Oreodonts

There are several genres of oreodonts, but their collective family is Merycoidodontid. If you search for Merycoidodontid on the Paleobiology Database (19/June/2022) you get multiple occurrences in Florida where there is a university and natural history museum actively supporting and engaged in field work and research. There is a Louisiana report of an occurrence, several Texas reports, and many reports from the western USA, but no reports from Georgia.

The first report of a fossil from a family, genus, or species in a state or region is always a worthwhile publication. This snout is certainly a candidate for a peer-review state or regional publication and would serve to expand the known range of oreodonts. It would date to the Late Eocene, roughly 35 million years old.

To borrow from Britannica online encyclopedia (edited).

Oreodont; any member of a diverse group of extinct herbivorous North American, cud-chewing, hoofed animals that lived from the Middle Eocene through the end of the Miocene (about 40 million and 5.3 million years ago). They’re often compared to sheep in size and shape, but they are more closely related to camels, but the camel relation is still distant. Oreodonts were unlike any living mammal group in the structure of their skeleton and dentition. They diversified during the period when Earth’s climate was cooling from the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) about 55.8 million years ago and reached their maximum diversity during the relatively cool Oligocene Epoch (34 million to 23 million years ago). They were likely herd animals.

There are several genres of oreodonts, but their collective family is Merycoidodontid. If you search for Merycoidodontid on the Paleobiology Database (19/June/2022) you get multiple occurrences in Florida where there is a university and natural history museum actively supporting and engaged in field work and research. There is a Louisiana report of an occurrence, several Texas reports, and many reports from the western USA, but no reports from Georgia.

The first report of a fossil from a family, genus, or species in a state or region is always a worthwhile publication. This snout is certainly a candidate for a peer-review state or regional publication and would serve to expand the known range of oreodonts. It would date to the Late Eocene, roughly 35 million years old.

To borrow from Britannica online encyclopedia (edited).

Oreodont; any member of a diverse group of extinct herbivorous North American, cud-chewing, hoofed animals that lived from the Middle Eocene through the end of the Miocene (about 40 million and 5.3 million years ago). They’re often compared to sheep in size and shape, but they are more closely related to camels, but the camel relation is still distant. Oreodonts were unlike any living mammal group in the structure of their skeleton and dentition. They diversified during the period when Earth’s climate was cooling from the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) about 55.8 million years ago and reached their maximum diversity during the relatively cool Oligocene Epoch (34 million to 23 million years ago). They were likely herd animals.

No, Thank You

Next, I approached a natural history museum in the Atlanta area where I was known. I've guided members of their executive staff on Coastal Plain fossil hunts, spoken at the museum, participated in multiple events, and during museum hosted suppers where I was a guest, I've heard museum officers state that Georgia fossils should be housed in Georgia.

I was completely open about what the fossil’s provenance, about the circumstances of collection and how it came to be loaned to me. My friend was just trying to do something for science. I was told in no uncertain terms that since the fossil was collected without landowner permission the museum would not be interested in participating.

I countered that the fossil was collected more than a decade ago and all a publication really needs to say is that it came from the Tivola Limestone of Houston County. There are half a dozen large exposures in Houston County. That would be a factual statement and protect both the collector and the landowner while encouraging no one to go looking for more.

No, thank you, was the reply which ended the argument. They wouldn’t risk the reputation of the museum on a single fossil. I understood their position.

Nothing worthwhile is ever simple.

Next, I approached a natural history museum in the Atlanta area where I was known. I've guided members of their executive staff on Coastal Plain fossil hunts, spoken at the museum, participated in multiple events, and during museum hosted suppers where I was a guest, I've heard museum officers state that Georgia fossils should be housed in Georgia.

I was completely open about what the fossil’s provenance, about the circumstances of collection and how it came to be loaned to me. My friend was just trying to do something for science. I was told in no uncertain terms that since the fossil was collected without landowner permission the museum would not be interested in participating.

I countered that the fossil was collected more than a decade ago and all a publication really needs to say is that it came from the Tivola Limestone of Houston County. There are half a dozen large exposures in Houston County. That would be a factual statement and protect both the collector and the landowner while encouraging no one to go looking for more.

No, thank you, was the reply which ended the argument. They wouldn’t risk the reputation of the museum on a single fossil. I understood their position.

Nothing worthwhile is ever simple.

No Georgia Home for a Georgia Fossil

I spent another week or so sending queries to Georgia paleontologist but was finally forced to reach further afield. Trespassing to collect had left this Georgia fossil unwanted by any Georgia institution.

It was an institution outside Georgia which finally accepted the fossil. I’d spent a day in the field a few months earlier guiding one of their curators, that’s the very best way to build relationships in paleontology. We exchanged emails and images over the specimen.

The curator explained that trespassing to collect was an issue, but not an insurmountable one. He knew the chief geologist for that particular mine. Most regional geologist and paleontologist know each other at some level. In this case, he’d maintained a relationship simply because the Tivola and other sediments they mined were so rich in fossils, so he assisted her however he could. My friend went on to explain that she, of course, discouraged trespassing in the strongest possible terms, but recognized that it happens, nevertheless.

I answered that if a paper is written & published, I’d like GeorgiaFossils.com to have an opportunity to cover the process with a webpage published after the paper. Also, I’d like both the collector and GeorgiaFossils.com to be officially acknowledged and thanked for contributing to science in any published paper.

Papers like this tend to have long legs.

In days, my friend agreed to donate the fossil on the above conditions and the institution agreed to letting GeorgiaFossils.com do a page on “How to Bring Your Fossil to Science”. I carefully package the fossil and personally sent it to the institution via UPS. A few days later I had confirmation that it had safely arrived.

He agreed to donate the fossil. A fossil he'd collected himself and held for over a decade, he donated it to the institution for the sake of advancing science. If that's not sacrificing something for science, I don't know what is. Sadly, he didn't get the credit he richly deserved.

Papers like this tend to have long legs.

In days, my friend agreed to donate the fossil on the above conditions and the institution agreed to letting GeorgiaFossils.com do a page on “How to Bring Your Fossil to Science”. I carefully package the fossil and personally sent it to the institution via UPS. A few days later I had confirmation that it had safely arrived.

He agreed to donate the fossil. A fossil he'd collected himself and held for over a decade, he donated it to the institution for the sake of advancing science. If that's not sacrificing something for science, I don't know what is. Sadly, he didn't get the credit he richly deserved.

It was just about this time that the Covid Pandemic lockdowns occurred, the universities and museums were all shuttered. By trade I’m a Parts Manager for a heavy equipment dealer, as such I was deemed infrastructure essential and worked through the Pandemic.

It was a year later before academia awoke from the pandemic and became active again. But patience is usually rewarded and soon enough I had an email that the specimen had been scanned and confirmed as an oreodont. Furthermore it had been assigned to a promising grad student for research, write-up and submission for publication. I looked her up online, she seemed a good choice. I emailed her, offering any assistance she might need… no reply. It’s entirely possible that my email got caught in her spam.

It was a year later before academia awoke from the pandemic and became active again. But patience is usually rewarded and soon enough I had an email that the specimen had been scanned and confirmed as an oreodont. Furthermore it had been assigned to a promising grad student for research, write-up and submission for publication. I looked her up online, she seemed a good choice. I emailed her, offering any assistance she might need… no reply. It’s entirely possible that my email got caught in her spam.

Six months later, the continued silence from the grad student, the curator, and the institution’s officers was deafening. Emails sent, over the oreodont fossil or any other subject, received no reply.

Had the mine objected & refused co-operation? I didn't know, but it seemed abundantly clear that, for whatever reason, my relationship with this institution had taken a bad turn.

Had the mine objected & refused co-operation? I didn't know, but it seemed abundantly clear that, for whatever reason, my relationship with this institution had taken a bad turn.

Missed Opportunity

As mentioned, there are multiple Florida oreodont reports, but according to the Paleobiology Database the oldest Florida oreodont fossils are Oligocene, which began 33.9 million years ago, at least 1 million years younger than the Georgia find.

Again, according to the Paleobiology Database, the Louisiana and Texas oreodont fossils are dated to the Miocene epoch, so they're even younger, the Miocene began 23 million years ago. The Tivola Limestone is 35 million years old.

If we accept the Paleobiology Database as a scientifically valid, it would seem that my friend’s fossil is the oldest example of the oreodont family in the Southeast.

Not only is my friend's Tivola Limestone oreodont important from a geographic range perspective, it's also important from a chronological perspective, it shows that oreodonts populated the Southeast earlier than previously thought.

Therefore; my friend's fossil, collected from the Tivola Limestone while trespassing, which he'd held for a decade, is indeed a scientifically important fossil by any measure and will likely never be published or occur in the Paleobiology Database.

However, its story has been told here and more I cannot do.

As mentioned, there are multiple Florida oreodont reports, but according to the Paleobiology Database the oldest Florida oreodont fossils are Oligocene, which began 33.9 million years ago, at least 1 million years younger than the Georgia find.

Again, according to the Paleobiology Database, the Louisiana and Texas oreodont fossils are dated to the Miocene epoch, so they're even younger, the Miocene began 23 million years ago. The Tivola Limestone is 35 million years old.

If we accept the Paleobiology Database as a scientifically valid, it would seem that my friend’s fossil is the oldest example of the oreodont family in the Southeast.

Not only is my friend's Tivola Limestone oreodont important from a geographic range perspective, it's also important from a chronological perspective, it shows that oreodonts populated the Southeast earlier than previously thought.

Therefore; my friend's fossil, collected from the Tivola Limestone while trespassing, which he'd held for a decade, is indeed a scientifically important fossil by any measure and will likely never be published or occur in the Paleobiology Database.

However, its story has been told here and more I cannot do.

A Miocene Predator

As my oreodont saga unfolded, a friend (another advanced amateur) found a Miocene aged (at least 13 million year old) predator’s tooth in south Georgia. This would be a distant relative to modern wolves and dogs, so it was a powerful, advanced predator. Such teeth have been suspected, but only reported in a general sense once.

There’s a 1974 report mentioning a similar tooth from the same area but the fossil was lost by the university housing it and cannot be confirmed or compared to the newly found tooth.

The science has progressed a great deal since 1974. The new specimen could easily establish a new species or extend the range of a known species. A Georgia paleontologist offered to assist my friend in publication but that was two years ago (?) and no action has been taken.

My friend considering an attempt self-author and publish through a state science journal.

As my oreodont saga unfolded, a friend (another advanced amateur) found a Miocene aged (at least 13 million year old) predator’s tooth in south Georgia. This would be a distant relative to modern wolves and dogs, so it was a powerful, advanced predator. Such teeth have been suspected, but only reported in a general sense once.

There’s a 1974 report mentioning a similar tooth from the same area but the fossil was lost by the university housing it and cannot be confirmed or compared to the newly found tooth.

The science has progressed a great deal since 1974. The new specimen could easily establish a new species or extend the range of a known species. A Georgia paleontologist offered to assist my friend in publication but that was two years ago (?) and no action has been taken.

My friend considering an attempt self-author and publish through a state science journal.

In Closing

As stated at the top of this piece, Georgia amateurs lack a path towards getting scientifically important fossils published in peer-reviewed literature. This is often true for both beginners and advanced amateurs with field experience and extensive contacts, and the publication of scientifically significant finds is important.

Our understanding Georgia’s natural history can only be expanded and documented by publishing finds in peer-reviewed journals.

As stated at the top of this piece, Georgia amateurs lack a path towards getting scientifically important fossils published in peer-reviewed literature. This is often true for both beginners and advanced amateurs with field experience and extensive contacts, and the publication of scientifically significant finds is important.

Our understanding Georgia’s natural history can only be expanded and documented by publishing finds in peer-reviewed journals.

To the friend who first loaned and then donated the fossil in the hope of supporting science, I can only offer my apologies. We made a sincere, honest effort. Sometimes the ivory tower of science defeats both its allies and itself.