24: Georgia Geologic Survey

A Bit of History

By Thomas Thurman

March 2015

With guest essay by

William McLemore

Former Georgia State Geologist

Georgia needs the Georgia Geologic Survey. The Survey was opened in 1836 and "abolished" in 2004.

The State Survey needs to be restored, legislatively mandated, funded, enhanced, and folded into the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division where it can help us use our resources wisely and prepare Georgians for our future.

Georgia is the only Southeastern state without a state geologic survey office and lacking a geologic education outreach program.

The United States Coastal Plain stretches from Texas to the peninsula of Massachusetts. Looking west and up the Mississippi River basin is the Gulf Coastal Plain. The whole Atlantic seaboard encompasses the Atlantic Coastal Plain. The Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plains converge in Georgia and their meeting is marked by the buried Gulf Trough and the Suwannee Current which formed it.

Teachers are told nothing of this elsewhere. This website is the only free-access online source of information for either. Georgia needs the Georgia Geologic Survey.

The Georgia Fossil Collection

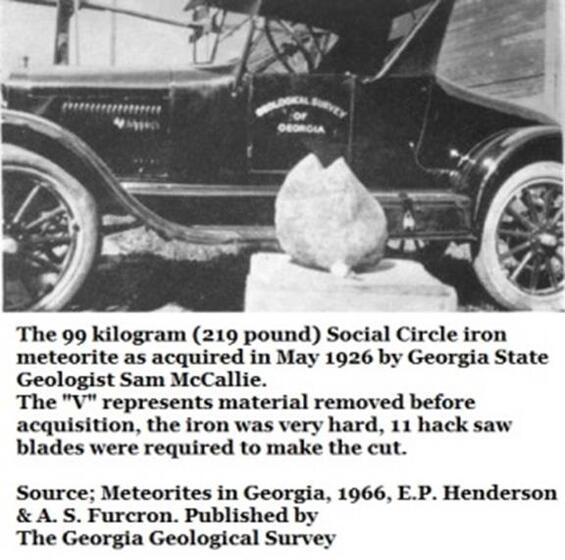

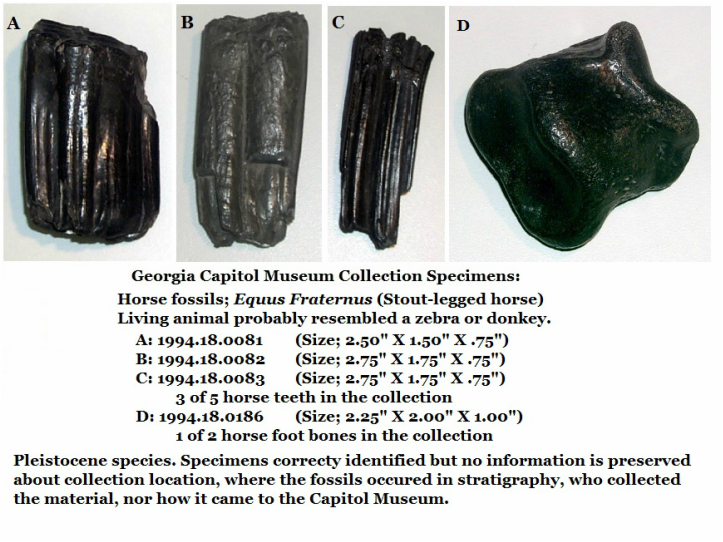

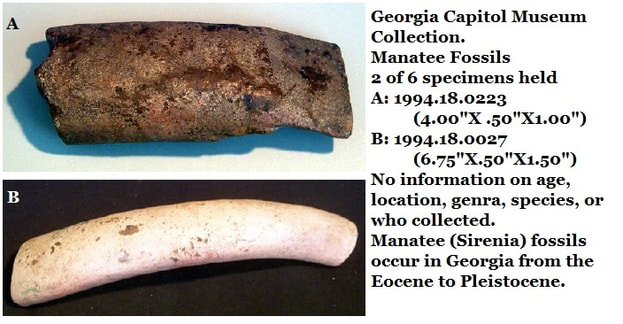

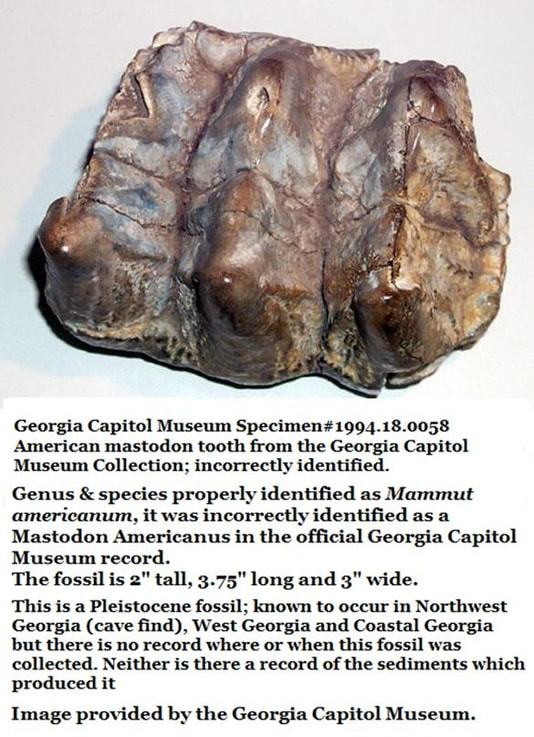

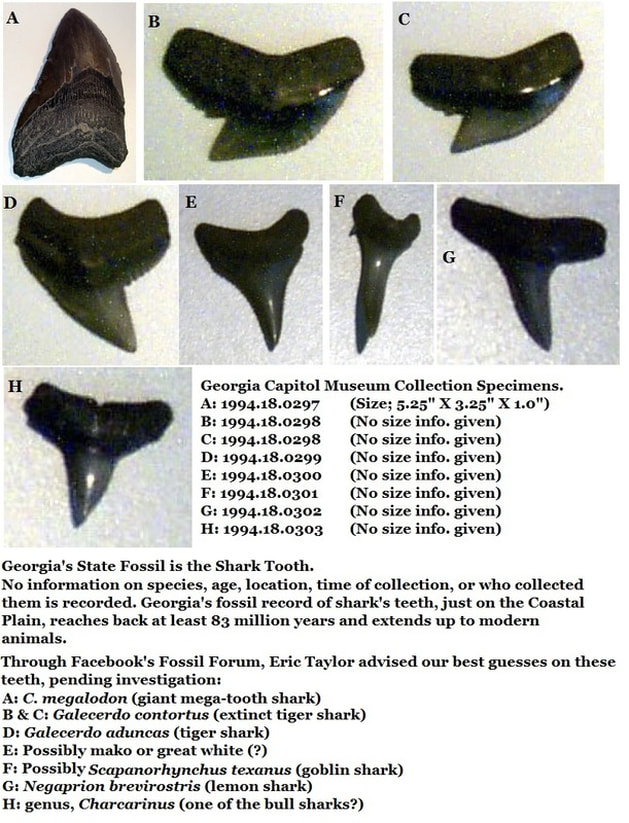

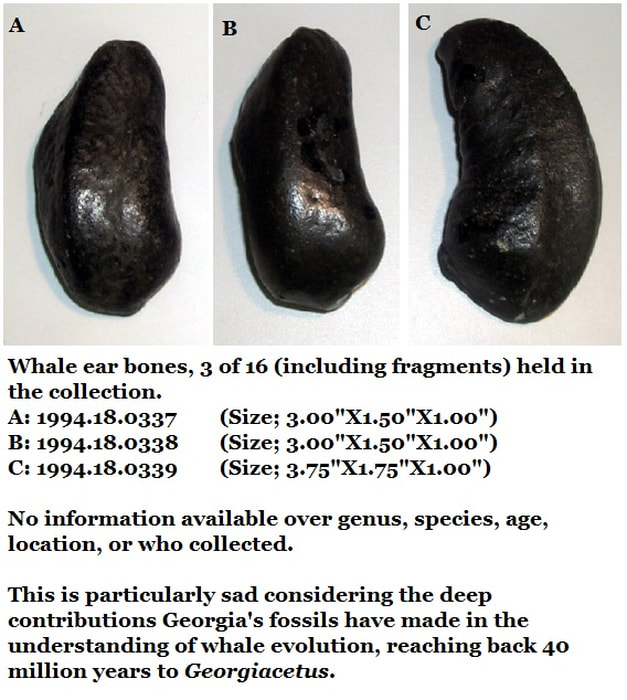

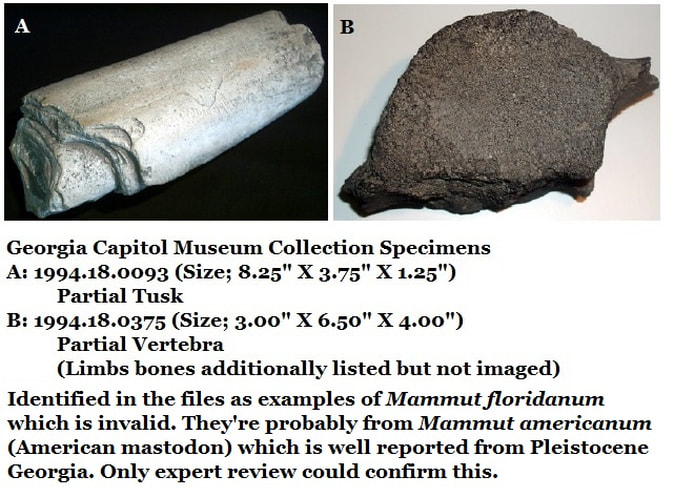

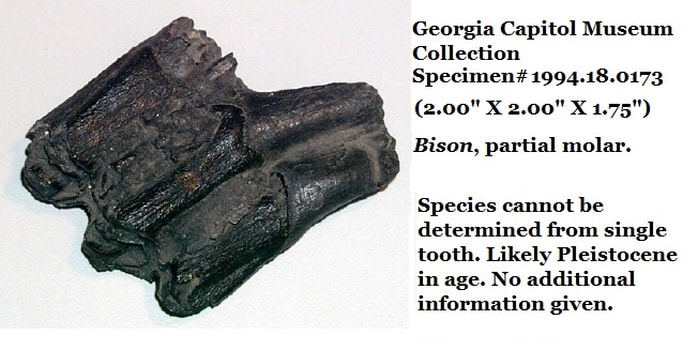

The specimens shown on these pages are from official pdf files of the Georgia Capitol Museum fossil collection, most of which were updated in 2008. These files were shared with me in February 2012 by Timothy Frilingos, Director of the Georgia Capitol Museum.

Sadly of the 54 files shared few, if any, are complete, current, or accurate. The museum was apparently unaware of this. Many of the specimens are only partially identified. There is little to no information about the age of specimens, the site and time of collection or how they fit into the stratigraphy. This makes their usefulness to research very limited.

According to the information shared by William McLemore (Georgia State Geologist from 1979 to 2005) the Capitol Museum’s fossil collection was once in the possession of the Georgia Geologic Survey but was transferred to the state capitol building before he became State Geologist in 1979.

Only paleontology, in its many forms, reveals Georgia’s history of climate change. Georgia’s fossil record of the last 100,000 years reveals many dramatic shifts in climate; with different plants occupying our state at different times. This has implications which will interest our farmers.

What Would a Survey Do?

McLemore reports that the Georgia Geologic Survey never held a legislative mandate but served at the pleasure of the Governor and the General Assembly. It had always known a budgetary rollercoaster but as we’ve seen it had still produced produce solid research.

It needs to be restored then given the below directives.

McLemore reports that the Georgia Geologic Survey never held a legislative mandate but served at the pleasure of the Governor and the General Assembly. It had always known a budgetary rollercoaster but as we’ve seen it had still produced produce solid research.

It needs to be restored then given the below directives.

- Scientific; Continue and expand research toward the goals of defining and understanding our geologic history and provinces.

- It will be the Survey’s task to establish and publically report the general geologic history of Georgia, with academic research filling in the details.

- The Survey will be charged with creating and maintaining a publically available digital three dimensional map of Georgia’s geologic provinces based on field research, well logs, core logs and core samples.

- They are to establish and maintain a publically available free access, online, Georgia Geologic Survey Library.

- The survey will assist, support, and advise the universities on their own research programs. They will correlate work between different schools and programs.

- They will incorporate those academic findings into the survey library.

- The survey will encourage and support interdisciplinary research both within the Department of Natural Resources and beyond it, as deemed beneficial.

- Economic; The survey is be tasked to locate usable natural resources, define their potential value, assesses the potential risks in development and advise the state on marketability.

- They should both advise and oversee exploitation of Georgia’s natural mineral resources.

- They will be responsible for the issuance of exploitation permits for all state mineral resources.

- They will strictly enforce all regulations with financially stiff mandatory penalties up to and including the loss of mining and/or resource use rights.

- Education; Establishment of a state funded and maintained Georgia’s Paleontology & Geology web site aimed towards education.

- Correcting, expanding, and maintaining the Georgia Capitol Museum Fossil Collection.

- Forming education alliances with mutually supportive cross-discipline educational material for other offices in the GA DNR; Coastal Resources, Historical Preservation, State Parks & Historic Sites, Wildlife Resources.

- Show the geologic history of our parks and recreation sites.

- Wildlife resource management should include information over past species and how changing climates of the past impacted todays distribution of species.

- Selected historically important mining pits could be preserved as is, with guided public fossil hunting seasonally allowed for future public interest, research, and educational purposes (research & guided teacher led educational field trips should be easily, frequently and freely available).

A Brief History of the Georgia Geological Survey

The below is from the former “About Us” icon of the Georgia Geologic Survey Store. That web site is no longer active.

1836: State supported geologic work in Georgia began with the four year appointment of John Cotting as State Geologist. Valuable mineral deposits as well as the measurement of magnetic variations in the state were noted during this first Survey.

1874: A second Survey was established and over its seven year duration additional mineral resources including gold were studied in the state.

1890: The Geological Survey of Georgia was established for the third time in 1890 and has operated continuously since then under various names.

1943: The Georgia Geologic Survey became the Department of Mines, Mining, and Geology of the State Division of Conservation.

1972: Under the Department of Natural Resources, it became the Earth and Water Division and was subsequently renamed the Geologic and Water Resources Division (1976).

1978: Again named the Georgia Geologic Survey, it was established as a branch of the Environmental Protection Division of the Department of Natural Resources.

2004: In late 2004 the Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished.

The below is from the former “About Us” icon of the Georgia Geologic Survey Store. That web site is no longer active.

1836: State supported geologic work in Georgia began with the four year appointment of John Cotting as State Geologist. Valuable mineral deposits as well as the measurement of magnetic variations in the state were noted during this first Survey.

1874: A second Survey was established and over its seven year duration additional mineral resources including gold were studied in the state.

1890: The Geological Survey of Georgia was established for the third time in 1890 and has operated continuously since then under various names.

1943: The Georgia Geologic Survey became the Department of Mines, Mining, and Geology of the State Division of Conservation.

1972: Under the Department of Natural Resources, it became the Earth and Water Division and was subsequently renamed the Geologic and Water Resources Division (1976).

1978: Again named the Georgia Geologic Survey, it was established as a branch of the Environmental Protection Division of the Department of Natural Resources.

2004: In late 2004 the Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished.

Georgia State Geologists

1836-1840 John R. Cotting

1874-1881 George Little

1890-1893 Joseph W. Spencer

1893-1908 William S. Yeates

1908-1933 Samuel W. McCallie

1933-1938 Richard W. Smith

1938-1964 Garland Peyton

1964-1969 A. Sydney Furcron

1969-1972 Jesse H. Auvil, Jr

1972-1978 Sam M. Pickering, Jr

1979-2005 William H. McLemore

2006 - 2022 Jim Kennedy

2022 - 2024 Office Unoccupied

2024- Edward Rooks

1836-1840 John R. Cotting

1874-1881 George Little

1890-1893 Joseph W. Spencer

1893-1908 William S. Yeates

1908-1933 Samuel W. McCallie

1933-1938 Richard W. Smith

1938-1964 Garland Peyton

1964-1969 A. Sydney Furcron

1969-1972 Jesse H. Auvil, Jr

1972-1978 Sam M. Pickering, Jr

1979-2005 William H. McLemore

2006 - 2022 Jim Kennedy

2022 - 2024 Office Unoccupied

2024- Edward Rooks

Georgia Geologic Survey

Guest Essay

By William McLemore

Lightly edited, March 8, 2015 comments from William McLemore, Georgia State Geologists, 1979-2005.

The Geologic Survey (or its predecessors) were housed in the Agriculture Building from about 1955 to 2010. Prior to that, the agency was housed in the Capital. The rock, mineral, and fossil collections were moved from the Agriculture Building to the Capital sometime between 1972 and 1979, when I became State Geologist. I remember seeing the collection in 1972, while visiting the agency; however, by April of 1979, when I became State Geologist, they were no longer there. The status and condition of the various collections, for practical purposes, were out of the hands of the Geologic Survey by the late 1970s.

1. The Survey began in very late 1899 and continued until late 2004. In the early days, there was only limited funding and staff. However, beginning with the Carter administration (1977-1981), funding levels increased significantly and a number of new employees were brought on board. Funding was relatively good (million dollars plus per year) up until the end. Without Carter's support, it is likely that the Survey would have ended in the 1970s. Some of the very best technical work (and perhaps the best) was done in the last ten years of the Survey.

2. In 1978, the Survey was reorganized with emphasis being placed on applied geology studies that had the potential to impact the daily lives of Georgians; it was folded into the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division. This meant that hydrologic studies, which had not received much attention in the past, were now placed on even par with geologic studies. At the same time, the Department of Audits reviewed the Survey's activities with the intent of improving agency efficiency and avoiding duplication of work effort.

Some of the findings of the audit were:

(a) Academic geologic research was a function of the University System, not the Department of Natural Resources and the Department should focus on applied studies.

(b) Employees should be multi-functional and be able to do a variety geologic studies in several geologic fields.

(c) There was a need for a strong program of comprehensive technical files; but there was little need for maintaining collections of rocks, minerals, and fossils (Note: funds, however, were made available to contract for such studies and/or maintaining such collections);

(d) Geologic investigations should be cost-effective and some activities that required specialized staff should be "farmed out" to federal agencies and/or the University System;

(e) Extreme care should be taken not to augment the mineral activities of mining companies.

(f) The Survey should develop a program of "peer review" for investigative studies and the State Geologist should be prepared to "personally stand behind" all Survey publications.

3. It is true that a number of mineral, rock, and fossils were exposed to the elements in the late 1970s and very early 1980s, when the Survey was using a derelict warehouse at the old Farmer's Market. In the early 1980s, however, funds were secured and a new warehouse was established in the south side of Atlanta. Some unidentifiable samples were disposed in a landfill and some duplicate paper documents were recycled. Materials for which there was little identifiable need were "donated" to colleges and universities.

4. A financial audit was performed on the Survey in 2005; and it was determined that the Survey employed fiscally and legally sound practices. No financial irregularities were uncovered.

5. After early 2004, it was apparent that the Director of EPD (my boss) and I did not agree on the role of the Survey. However, since I would be retiring in 2005, we just developed an agreement to disagree.

6. The Survey maintained a fiscally-sound publications sales office throughout my tenure. At the time of my retirement at the end of August of 2005, all financial records and technical files were in order.

7. By the mid 1980's, state and federal funds increasing became available for regulatory activities. This meant that in addition to performing technical investigations, the Survey also performed some regulatory activities. This was an expansion of activities not a reduction of activities. Also by doing this, employees performing technical investigations could achieve promotions by switching to regulatory programs. This was strictly a voluntary activity, however.

The Demise of the Survey can be attributed to four factors; namely:

(Guest essay by William McLemore)

A. The Survey never had a legislative mandate; the agency merely served at the whim of Governor and or the General Assembly.

a. This meant that the agency was always in competition with other State of Georgia agencies for funding and positions. At best, the agency's existence was always precarious.

b. In 1978, the Survey came close to being shut down; fortunately, this did not happen because the Director of EPD and a few Department of Natural Resources Board Members saw the value of the agency.

B. The prison construction and inmate incarceration program of the late 1980s and early 1990s took away most of Georgia's available funds and put the State in a permanent position of almost always coming close to budgetary deficits.

C. In 1991-1992, Georgia, for practical purposes, ran out of money and was faced with the position of not being able to pay its bills.

a. To fix this situation, all agencies were asked to reduce State funded staff. Inasmuch as most of the Survey geologists were funded with State dollars, there had to be a significant reduction in the technical investigations as the geologists performing these studies could no longer be paid.

b. This was an unhappy situation; but the negative ramifications were state-wide and were not restricted to the Geologic Survey per se.

c. On an optimistic note, transfers were affected for the majority of Survey geologists and most continued their employment but doing somewhat different work.

D. In 2003, a new Director of EPD was appointed by the new Governor. The new Director, in late 2004, made a unilateral decision to close the Survey (and some other EPD agencies) and redistribute existing personnel. I was never informed of this, merely learning about it through the "grapevine".

Guest Essay

By William McLemore

Lightly edited, March 8, 2015 comments from William McLemore, Georgia State Geologists, 1979-2005.

The Geologic Survey (or its predecessors) were housed in the Agriculture Building from about 1955 to 2010. Prior to that, the agency was housed in the Capital. The rock, mineral, and fossil collections were moved from the Agriculture Building to the Capital sometime between 1972 and 1979, when I became State Geologist. I remember seeing the collection in 1972, while visiting the agency; however, by April of 1979, when I became State Geologist, they were no longer there. The status and condition of the various collections, for practical purposes, were out of the hands of the Geologic Survey by the late 1970s.

1. The Survey began in very late 1899 and continued until late 2004. In the early days, there was only limited funding and staff. However, beginning with the Carter administration (1977-1981), funding levels increased significantly and a number of new employees were brought on board. Funding was relatively good (million dollars plus per year) up until the end. Without Carter's support, it is likely that the Survey would have ended in the 1970s. Some of the very best technical work (and perhaps the best) was done in the last ten years of the Survey.

2. In 1978, the Survey was reorganized with emphasis being placed on applied geology studies that had the potential to impact the daily lives of Georgians; it was folded into the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division. This meant that hydrologic studies, which had not received much attention in the past, were now placed on even par with geologic studies. At the same time, the Department of Audits reviewed the Survey's activities with the intent of improving agency efficiency and avoiding duplication of work effort.

Some of the findings of the audit were:

(a) Academic geologic research was a function of the University System, not the Department of Natural Resources and the Department should focus on applied studies.

(b) Employees should be multi-functional and be able to do a variety geologic studies in several geologic fields.

(c) There was a need for a strong program of comprehensive technical files; but there was little need for maintaining collections of rocks, minerals, and fossils (Note: funds, however, were made available to contract for such studies and/or maintaining such collections);

(d) Geologic investigations should be cost-effective and some activities that required specialized staff should be "farmed out" to federal agencies and/or the University System;

(e) Extreme care should be taken not to augment the mineral activities of mining companies.

(f) The Survey should develop a program of "peer review" for investigative studies and the State Geologist should be prepared to "personally stand behind" all Survey publications.

3. It is true that a number of mineral, rock, and fossils were exposed to the elements in the late 1970s and very early 1980s, when the Survey was using a derelict warehouse at the old Farmer's Market. In the early 1980s, however, funds were secured and a new warehouse was established in the south side of Atlanta. Some unidentifiable samples were disposed in a landfill and some duplicate paper documents were recycled. Materials for which there was little identifiable need were "donated" to colleges and universities.

4. A financial audit was performed on the Survey in 2005; and it was determined that the Survey employed fiscally and legally sound practices. No financial irregularities were uncovered.

5. After early 2004, it was apparent that the Director of EPD (my boss) and I did not agree on the role of the Survey. However, since I would be retiring in 2005, we just developed an agreement to disagree.

6. The Survey maintained a fiscally-sound publications sales office throughout my tenure. At the time of my retirement at the end of August of 2005, all financial records and technical files were in order.

7. By the mid 1980's, state and federal funds increasing became available for regulatory activities. This meant that in addition to performing technical investigations, the Survey also performed some regulatory activities. This was an expansion of activities not a reduction of activities. Also by doing this, employees performing technical investigations could achieve promotions by switching to regulatory programs. This was strictly a voluntary activity, however.

The Demise of the Survey can be attributed to four factors; namely:

(Guest essay by William McLemore)

A. The Survey never had a legislative mandate; the agency merely served at the whim of Governor and or the General Assembly.

a. This meant that the agency was always in competition with other State of Georgia agencies for funding and positions. At best, the agency's existence was always precarious.

b. In 1978, the Survey came close to being shut down; fortunately, this did not happen because the Director of EPD and a few Department of Natural Resources Board Members saw the value of the agency.

B. The prison construction and inmate incarceration program of the late 1980s and early 1990s took away most of Georgia's available funds and put the State in a permanent position of almost always coming close to budgetary deficits.

C. In 1991-1992, Georgia, for practical purposes, ran out of money and was faced with the position of not being able to pay its bills.

a. To fix this situation, all agencies were asked to reduce State funded staff. Inasmuch as most of the Survey geologists were funded with State dollars, there had to be a significant reduction in the technical investigations as the geologists performing these studies could no longer be paid.

b. This was an unhappy situation; but the negative ramifications were state-wide and were not restricted to the Geologic Survey per se.

c. On an optimistic note, transfers were affected for the majority of Survey geologists and most continued their employment but doing somewhat different work.

D. In 2003, a new Director of EPD was appointed by the new Governor. The new Director, in late 2004, made a unilateral decision to close the Survey (and some other EPD agencies) and redistribute existing personnel. I was never informed of this, merely learning about it through the "grapevine".

Georgia Mineral and Fossil Collections

In a personal interview at his home Sam Pickering shared how at one point the Georgia Geologic Survey would provide free, properly identified and tagged mineral and fossil samples to any school which would provide a case.

Pickering would go on to become State Geologist and lead the effort to published the first Geologic Map of Georgia, the first print of that map hanging in his home office with the signatures of all the participating geologists. (This map is now at Fernbank Science Center, Atlanta)

As McLemore came onboard as State Geologist in 1979 the Georgia Geologic Survey was folded into the DNR’s Environmental Protection Division. This merging included a purging of excess material. The problem here is who decides what’s excess.

Science builds on past work so literature is vital in science; geology and paleontology is no exception. Pickering had amassed a large collection of reference literature from state geological surveys across the USA. Almost all of this went into the trash; researchers were only allowed to retain material covering the states immediately surrounding Georgia.

Employees from that time report that lab tools were discarded; slab saws, polishing tables and wheels, microscopes and other equipment went away. Among other things they lost the ability to produce their own thin sections for research. This degraded the Survey’s ability.

For some years the Survey had kept a warehouse in southwest Atlanta where specimens, equipment, documents and other material was kept. It had not enjoyed proper maintenance and was broken into more than once. With the re-organization this warehouse was given up and a great deal of material including specimens and documents, were simply discarded.

In a personal interview at his home Sam Pickering shared how at one point the Georgia Geologic Survey would provide free, properly identified and tagged mineral and fossil samples to any school which would provide a case.

- Pickering chuckled as he told the story of once being held at gun-point on Graves Mountain while collecting samples for a school; mine employees didn’t realize he was collecting with permission from the land owners. This was in the early to mid-1970s.

Pickering would go on to become State Geologist and lead the effort to published the first Geologic Map of Georgia, the first print of that map hanging in his home office with the signatures of all the participating geologists. (This map is now at Fernbank Science Center, Atlanta)

As McLemore came onboard as State Geologist in 1979 the Georgia Geologic Survey was folded into the DNR’s Environmental Protection Division. This merging included a purging of excess material. The problem here is who decides what’s excess.

Science builds on past work so literature is vital in science; geology and paleontology is no exception. Pickering had amassed a large collection of reference literature from state geological surveys across the USA. Almost all of this went into the trash; researchers were only allowed to retain material covering the states immediately surrounding Georgia.

Employees from that time report that lab tools were discarded; slab saws, polishing tables and wheels, microscopes and other equipment went away. Among other things they lost the ability to produce their own thin sections for research. This degraded the Survey’s ability.

For some years the Survey had kept a warehouse in southwest Atlanta where specimens, equipment, documents and other material was kept. It had not enjoyed proper maintenance and was broken into more than once. With the re-organization this warehouse was given up and a great deal of material including specimens and documents, were simply discarded.

Research & Research Lost

As we’ve seen throughout the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s the Georgia Geologic Survey was very active in building a strong scientific base of research and literature. So the Survey adapted to the merger with the DNR and the science continued. This peaked during McLemore’s tenure in the 1980s and 1990s with several splendid works of research published over Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

During this period the upper Coastal Plain, kaolin deposits, Gulf Trough and Suwannee Current were well researched and described in detail. Conditions during the Eocene, and Oligocene were examined and large scale research papers, maps and atlases with extensive field work were compiled, completed and published. The superb work of Paul F. Huddlestun, John Hetrick, Michael S. Friddell, Earl A. Shapiro, and others who greatly increasing our understanding of our state.

There was intensive fieldwork, specimens collected, defined, cataloged and stored. Many core samples were painstakingly taken, described, and preserved for further future analysis.

Taking core samples is expensive, but they have great scientific and economic value. Core samples allow subsurface sediments to be mapped in detail. These core samples and maps not only reveal our past but guide investments into the state’s economic resources.

During his research Paul Huddlestun had taken many core samples from various points on our Coastal Plain, they were fundamental to creating the research published by the Survey during the highly active period from the 1980s to the turn of the century.

When the Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished and ongoing work completed warehouses and offices were cleared and Huddlestun’s Coastal Plain core samples were simply discarded by the state. This was in the 2005-2010 time frame.

Survey geologists acting on their own tried to find homes for important specimens, documents and cores samples. They wanted to preserve their work. Some few samples ended up with the universities, but a great majority of the material reportedly went into the trash.

The loss of the core samples represents an irreplaceable, self-inflicted economic blow to the state; scientific data with both fiscal and research value is simply gone and replacing it, where possible, would require a huge financial investment.

One field geologist spoke of having a well equipped office in the Agriculture Building complete with tables, maps, and research literature which was simply emptied with the closing of the Survey. His office was packed-up and its contents hauled to the Georgia Archives, which he described as a “Black Hole”. He was assigned a cubicle while finishing up his project, he never again saw his maps and research material. “It felt like I’d been robbed.” He reported. “There were carefully noted maps which I’d spent months over, and I never saw them again; lost samples, documents and field notes. I tried several times to locate the contents of my old office but finally had to admit defeat.”

So much was lost.

As we’ve seen throughout the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s the Georgia Geologic Survey was very active in building a strong scientific base of research and literature. So the Survey adapted to the merger with the DNR and the science continued. This peaked during McLemore’s tenure in the 1980s and 1990s with several splendid works of research published over Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

During this period the upper Coastal Plain, kaolin deposits, Gulf Trough and Suwannee Current were well researched and described in detail. Conditions during the Eocene, and Oligocene were examined and large scale research papers, maps and atlases with extensive field work were compiled, completed and published. The superb work of Paul F. Huddlestun, John Hetrick, Michael S. Friddell, Earl A. Shapiro, and others who greatly increasing our understanding of our state.

There was intensive fieldwork, specimens collected, defined, cataloged and stored. Many core samples were painstakingly taken, described, and preserved for further future analysis.

Taking core samples is expensive, but they have great scientific and economic value. Core samples allow subsurface sediments to be mapped in detail. These core samples and maps not only reveal our past but guide investments into the state’s economic resources.

During his research Paul Huddlestun had taken many core samples from various points on our Coastal Plain, they were fundamental to creating the research published by the Survey during the highly active period from the 1980s to the turn of the century.

- Huddlestun has reveiwed and trevised many of these and shared them with GeorgiasFossils.com for posting

- See Section 28 of this website

When the Georgia Geologic Survey was abolished and ongoing work completed warehouses and offices were cleared and Huddlestun’s Coastal Plain core samples were simply discarded by the state. This was in the 2005-2010 time frame.

Survey geologists acting on their own tried to find homes for important specimens, documents and cores samples. They wanted to preserve their work. Some few samples ended up with the universities, but a great majority of the material reportedly went into the trash.

The loss of the core samples represents an irreplaceable, self-inflicted economic blow to the state; scientific data with both fiscal and research value is simply gone and replacing it, where possible, would require a huge financial investment.

One field geologist spoke of having a well equipped office in the Agriculture Building complete with tables, maps, and research literature which was simply emptied with the closing of the Survey. His office was packed-up and its contents hauled to the Georgia Archives, which he described as a “Black Hole”. He was assigned a cubicle while finishing up his project, he never again saw his maps and research material. “It felt like I’d been robbed.” He reported. “There were carefully noted maps which I’d spent months over, and I never saw them again; lost samples, documents and field notes. I tried several times to locate the contents of my old office but finally had to admit defeat.”

So much was lost.

I had these comments from a paleontologist in Florida who is very familiar with the work of the Georgia geologic Survey.

"I enjoyed looking over your GA fossil website. Georgia has so much to offer to paleo-researchers. I’ve worked (and published) with a number of GA colleagues (Paul H., Burt Carter, Sally Walker, Alex Kittle, etc.) and have several on-going GA-related projects in the works."

"Here, (Florida) our focus is primarily the Southeastern USA and circum-Caribbean and we house over 100,000 fossils from your state (Georgia) with more coming in each year."

"I too was appalled at the loss of the GA Survey and tried have their invertebrate paleontology collections transferred here. Unfortunately, I was too late for most of it. I did locate some 10 cabinets of material at UGA but the two times I visited no one was available to show the material to me (they are in a basement in one of the Geology areas). If you locate other materials I would be very interested."

"I know the invaluable GA cores were discarded!!! INSANE."

"I enjoyed looking over your GA fossil website. Georgia has so much to offer to paleo-researchers. I’ve worked (and published) with a number of GA colleagues (Paul H., Burt Carter, Sally Walker, Alex Kittle, etc.) and have several on-going GA-related projects in the works."

"Here, (Florida) our focus is primarily the Southeastern USA and circum-Caribbean and we house over 100,000 fossils from your state (Georgia) with more coming in each year."

"I too was appalled at the loss of the GA Survey and tried have their invertebrate paleontology collections transferred here. Unfortunately, I was too late for most of it. I did locate some 10 cabinets of material at UGA but the two times I visited no one was available to show the material to me (they are in a basement in one of the Geology areas). If you locate other materials I would be very interested."

"I know the invaluable GA cores were discarded!!! INSANE."

Tellus to the Rescue

In 2009 Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville, Georgia picked up part of the stored Georgia mineral collection from the Georgia Capitol Museum. Timothy Frilingos, Director of the Georgia Capitol Museum confirms that their stored collection was transferred to Tellus. Tellus reports that his included neither fossils nor material on exhibit in the Capitol.

According to Tellus; Around 2010 The Georgia Environmental Protection Division announced that the remaining Georgia Geologic Survey employees were finishing up projects after being disbanded and were to clear out all offices in the Agriculture building in downtown Atlanta.

At that time Tellus was contacted again and asked if they wanted any of the additional material from the Georgia collection; they picked up two cabinets, two cases of minerals and rocks, framed maps, library material and various other items; but again this included no fossils.

Between the two transfers, it’s believed that Tellus holds about 90% of the Georgia mineral collection. Amy Gramsey, Collections Manager at Tellus has done a superb job of reassembling Georgia’s mineral collection and expressed her sincere respect for the professionalism in the Georgia Geologic Survey’s original research and collection practices.

Tellus also reportedly holds the original Georgia Geologic Survey Ledger; which some of the former geologists working for the Survey describe as a large leather scrapbook and the very cornerstone of the Survey’s history. We look forward to it being published at some point; it would be intriguing to see what’s recorded.

Pending further information coming to light, this is as far as the author has been able to track Georgia’s historic Fossil Collection. Beyond the material on display at the Capitol Museum there are other specimens present in the literature which cannot currently be accounted for.

In 2009 Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville, Georgia picked up part of the stored Georgia mineral collection from the Georgia Capitol Museum. Timothy Frilingos, Director of the Georgia Capitol Museum confirms that their stored collection was transferred to Tellus. Tellus reports that his included neither fossils nor material on exhibit in the Capitol.

According to Tellus; Around 2010 The Georgia Environmental Protection Division announced that the remaining Georgia Geologic Survey employees were finishing up projects after being disbanded and were to clear out all offices in the Agriculture building in downtown Atlanta.

At that time Tellus was contacted again and asked if they wanted any of the additional material from the Georgia collection; they picked up two cabinets, two cases of minerals and rocks, framed maps, library material and various other items; but again this included no fossils.

Between the two transfers, it’s believed that Tellus holds about 90% of the Georgia mineral collection. Amy Gramsey, Collections Manager at Tellus has done a superb job of reassembling Georgia’s mineral collection and expressed her sincere respect for the professionalism in the Georgia Geologic Survey’s original research and collection practices.

Tellus also reportedly holds the original Georgia Geologic Survey Ledger; which some of the former geologists working for the Survey describe as a large leather scrapbook and the very cornerstone of the Survey’s history. We look forward to it being published at some point; it would be intriguing to see what’s recorded.

Pending further information coming to light, this is as far as the author has been able to track Georgia’s historic Fossil Collection. Beyond the material on display at the Capitol Museum there are other specimens present in the literature which cannot currently be accounted for.