South Houston County Fossils

Roadside Collecting

By Thomas Thurman

Be a Citizen Scientist exploring a lost, ancient Georgia sea. In Houston County, Georgia, you can collect fossilized sea shells at least 23 million years old.

They're from the Oligocene Epoch which began 33.9 million years ago and ended 23 million years ago.

They're from the Oligocene Epoch which began 33.9 million years ago and ended 23 million years ago.

Large fossiliferous chert boulder supported by a tree on Hwy 26 in south Houston County

Large fossiliferous chert boulder supported by a tree on Hwy 26 in south Houston County

They lived just after Grande Coupure global extinction event which marks the Eocene- Oligocene boundary.

Re-crystallized sea shells, which glitter beautifully in the sun, are common in these deposits but vertebrate fossils are very rare as their populations were still rebounding. Jasper, agate and chalcedony are common; you'll also find iron based minerals such as geothite, limonite, and hematite.

Become a Citizen Scientist and assist in ongoing research by imaging and reporting to the author any sharks teeth or other vertebrate fossils you may find. You will find my email on the Author's Bio page.

Though serious research on these deposits began in 1911, they weren't properly understood until 197o when Sam Pickering published his survey of the area for the Georgia Geologic Survey. Pickering would go on to stand as the Georgia State Geologist from 1972 to 1978.

Details about the formation and research of these deposits can be found at the base of this page, after the tour text, under the heading "Georgia's Heritage of Research".

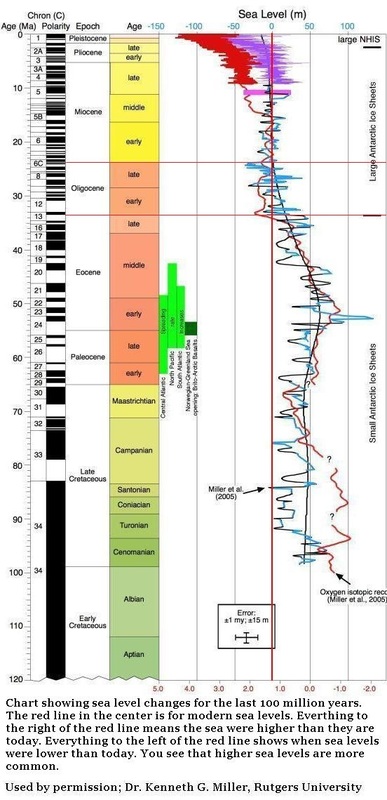

As the sea-level chart just below shows, global temperatures and coastlines remained restless throughout the Oligocene Epoch. (5)

Enjoy your tour and the beauty of rural Houston County!

Re-crystallized sea shells, which glitter beautifully in the sun, are common in these deposits but vertebrate fossils are very rare as their populations were still rebounding. Jasper, agate and chalcedony are common; you'll also find iron based minerals such as geothite, limonite, and hematite.

Become a Citizen Scientist and assist in ongoing research by imaging and reporting to the author any sharks teeth or other vertebrate fossils you may find. You will find my email on the Author's Bio page.

Though serious research on these deposits began in 1911, they weren't properly understood until 197o when Sam Pickering published his survey of the area for the Georgia Geologic Survey. Pickering would go on to stand as the Georgia State Geologist from 1972 to 1978.

Details about the formation and research of these deposits can be found at the base of this page, after the tour text, under the heading "Georgia's Heritage of Research".

As the sea-level chart just below shows, global temperatures and coastlines remained restless throughout the Oligocene Epoch. (5)

Enjoy your tour and the beauty of rural Houston County!

Some species you may find

Sand dollars & sea urchins.

Sand dollars & sea urchins.

- Gagaria mossomi Rare

- Clypeaster cotteaui Rare

- Cassidulus gouldi Common

- Glycymeris cookie Common

- Glycymeris suwaneensis Rare

- Pecten suwaneensis Rare

- Ostrea mauricensis Rare

- Lima halensis Rare

- Crassatellites paramesus Abundant

- Phacoides wacissanus Common

- Chion bainbridgensis Common

Begin Tour Here.

This tour can be done comfortably in 90 minutes from the time you leave I-75 at Exit 127 to the time you return to I-75 at Exit 135. Take your time, explore, and enjoy.

Please Be Respectful of Private Property.

1: Highway I-75 at Exit 127

This tour can be done comfortably in 90 minutes from the time you leave I-75 at Exit 127 to the time you return to I-75 at Exit 135. Take your time, explore, and enjoy.

Please Be Respectful of Private Property.

1: Highway I-75 at Exit 127

- The tour begins on Highway I-75 at Exit 127, Montezuma-Hawkinsville, Figure 1.

- At top of ramp you'll find a fuel & convenience store, this will be the last one for a while.

- From the I-75 exit ramp turn left (east) onto State Highway 26 in southern most Houston County.

- After .35 miles there will be a dirt road on your right; this is Henderson Springs Road.

- Turn right onto Henderson Springs Road.

2: Henderson Springs Road, Approximately 3.65 miles long. (This road will be followed to its end on County Line Road.)

- Notice the orange/red coloration of the road; the quartz sand is stained by oxidized iron (rust). Georgia’s red sands and clays are the remains from weathered mountains.

- After about a mile you will encounter a sharp left turn. (Figure 4) This is a good place for observations, park the car safely beyond the curve and walk back.

- Notice the embankment on the left in the crook of the curve.

- There is clear “stratification” or layering in the embankment.

- The upper sandy soil is light brown, even blond, while the lower sandy clay is mottled pink & tan. This pink & tan colored sandy clay is called the Perry Sand (Figures 5, 8, & 9) and is Middle Eocene Epoch in age, say 48.6 to 40.4 million years old. (Reference 2)

- These sediments were laid down independently. The upper is terrestrial, was created by wind & rain. The Perry Sand is marine, created by a shallow sea.

- Few, if any, fossils are present but if you pass a magnet over the embankment you’ll find many pea-sized pebbles with enough remaining iron to be strongly magnetic. (Figure 6) This is naturally occurring native iron as limonite pebbles.

- As a small business iron ore was actively mined from these deposits in the 1950s and 1960s about 10 miles away from this site.

- Notice that very few pebbles occur at the top of the embankment and few are present in the base. The pebbles are most numerous at the transition. (Figure 7)

- The lights color veins in the Perry Sand are kaolin deposits.

- Walk on through the curve and see the embankments beyond, mostly on the right side of the road. (Figure 10) Notice the rounded quartz and iron pebbles; the rounded edges are typical of material transported by water.

- A few small bits of chert may be seen with random fossils.

- On the embankments the veins of natural of the mottling becomes more evident. (Fig. 11)

- The surrounding fields were planted in cotton when visited by the author. (Figs. 12 & 13)

- Continue south on Henderson Springs Road.

A) From the sharp left turn there’s a drive just over a mile long to the tree line where there is a ditch to observe. Along the way keep a close eye on road-cuts (Figures 14, 15 & 16), as they become highly variable and no real explanation for this is offered in the geologic literature.

- Observe the top of the Perry Sand and see the roughly 1” thick line of pebbles which is characteristic of the formation’s upper horizon. (Figure 17)

- First fossil of the day; (Figure 18) Chamlys scallop shell cast (imprint) in chert. Inspection of the specimen revealed three separate scallops recorded, all about the same size, and a single, partial, Glycymeris clam shell. These are all small pelecypods and common finds. There are many other fossils in this small rock but as is often the case they are too partial to identify.

- Fossils may be collected from road shoulders and road-cuts. Take a few dornicks (throwing sized specimens) but please no excavating.

- These make good first fossils, good starter fossils, and good classroom specimens. Chert is a very hard and enduring rock. It tolerates rough handling. It can preserve amazingly fine detail and responds well to magnification. Also, you will frequently find small pockets in chert filled with tiny calcite or quartz crystals (re-crystallization) which sparkle handsomely.

- Moving further southwards towards the ditch we see the Perry Sand has taken a massive appearance with more consistent coloration (Figure 19) though it maintains that mottled appearance.

- Looking across the cotton field (Figure 20) we can see the upcoming drainage ditch as a line of taller vegetation at image left.

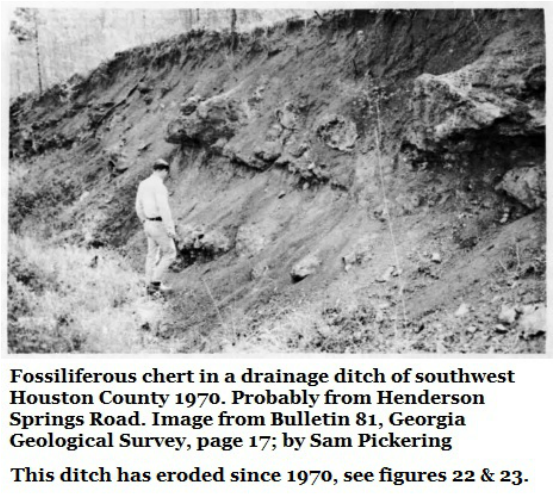

B) When Sam Pickering visited in 1969 he noted a drainage ditch with a wealth of fossils. The ditch is still here. It’s nearly overgrown with late summer’s kudzu. Decades of storms and winds have mellowed it. But fossils remain. (Figures 21, 22, & 23) Be respectful of private property.

C) The specimen shown in Figure 25 reveals recrystallization, which means essentially that the silica filled a cavity and coated it. Often these cavities will be tiny geode pockets.

- The ditch is private property but look along the edges of the dirt road, on the shoulders and in the road cuts. You’ll find fossilized dornicks good for collecting.

- When you look at Henderson Springs Road on Google Maps you’ll see a landmark icon for The Family Tree. Figure 24 shows The Family Tree remains and still shades its tiny family cemetery.

- The stretch of road between the ditch and the upcoming Big Creek is rich in fossils which can be collected from the shoulders. (Figures 26, 27 & 28) Tools are helpful but not necessary. There is a great wealth of material here.

- There are fossils in the bed of Big Creek (Figure 29). They’re also seen along the banks of the creek.

- There is also wildlife and nature to observe and enjoy (Figure 30). About a dozen female wild turkeys wandered across the dirt while I was there.

- Chert boulders occur in the shoulders of Henderson Springs Road on the south side of the creek. Figure 31 is an image of such a small boulder containing many recrystallized small clams. (Pelecypods) Some of these are small geode pockets, some are encrusted with tiny crystals and some are translucent chalcedony or jasper.

- Fossils continue to occur in the road banks (Figure 32) as we continue on to County Line Road.

3) Turn left, east, onto County Line Road. (Figure 33) The rest of the tour is on paved roads.

- County Line Road dead-ends into Elko Road after less than a mile.

- Turn left onto Elko Road and continue north.

- After about 1.5 miles we again encounter Big Creek.

- Coming downhill towards the creek watched the road cut walls for exposed rock.

- Figure 34 shows a small roadside chert boulder dense with clams (pelecypods), revealing the wealth of life in the sea which covered this site about 30 million years ago. (Notice the gray Banded Tussock Moth caterpillar, Halysidota tessellaris, just to the lower left of the rock pick grip.)

- Figure 35 shows a close-up of densely packed clam fossils.

- Figures 36 & 37 show road-cut outcrops of the same material and its typical stiff red clay along Elko Road just south of Big Creek. Figure 38 shows the Elko Road bridge over Big Creek and Figure 39 shows Big Creek.

- Keep an eye open for black and dark gray native material; in many spots a layer of iron ore overlies the chert. This is limonite-hematite, geothite (pronounced gur-tite), in the form of concretions, geodes, dornicks and iron-cemented sandstone up to ten feet thick.

- It can often be very attractive material.

- The iron ore originated from iron rich ground water filling cavities and precipitating out. There are iron ore fossils (but the iron content is too low for a magnet to stick) a friend had a complete, small sea urchin shell fossil Crassidulus gouldi in hematite which came from this material at a nearby location.

- Historically it has been actively mined and represented high quality ore up to 51% iron.

- Continue north on Elko Road, past Big Creek, to Stop sign

4) Turn right (east) onto Highway 26 for 5.40 miles

- Figure 40 & 41 represent interesting architecture of rural Georgia; a “sharecropper” or “shotgun” house and a collapsing tin roofed barn.

- Figures 42, 43, & 44 all represent a single shotgun house which happens to be built on a foundation of fossils. The stacked foundations stones are chert, the same fossiliferous chert we’re collecting. Much stronger material than concrete or cement.

- At about 2.8 miles on Highway 26 and approaching South Prong Elko Creek there’s a large boulder on the right side (south side) of the road; Figure 47. Safely pull off the road and inspect this road-cut. (Figures 47, 48, 49 & 50) A tree had grown up around this boulder. Look also to the roadside drainage ditches (Figure 47) and embankments (Figure 51 & 52).

- Don’t forget to enjoy the simple beauty of rural Georgia (Figure 53).

5) Turn left onto Pitts Road; 4.68 miles to Grovania Rd.

- Figure 54; Head north on Pitts Road towards Hayneville.

- (Figure 55) Lovely, fertile farmland

- Be observant of how locals have used the rocks at hand for landscaping. (Figures 56, 57, & 58)

- Straight through the stop sign and intersection of Klondike Road.

- To stop sign on Grovania Road.

- Turn right at stop sign.

- Grovania Road dead ends into Highway 341 (11) in .28 miles

6) Turn left (north) onto Highway 341 (11)

- After half a mile you’ll bear left and continue on Hwy 224 towards I-75.

- Hwy 341 (11) splits off to the right toward Warner Robins.

- On Hwy 224 It is approximate 9 miles to I-75 at Perry, Georgia; exit 135.

- There are multiple convenience stores and restaurants.

- TOUR END

Georgia's Heritage of Earth Research

The long Eocene Epoch ended with the Grand Coupure, a European term for the first serious global glaciation event Earth had seen in tens of millions of years. This glaciation drove a global extinction event which hit the seas hard. Globally, the event saw a rotation in species populations. The fossils found along this tour lived in the Oligocene Epoch, just after the Grand Coupure.

Throughout the Eocene the poles were likely ice free. During this global warmth the first modern whales emerged through the proto-whale line, which ended with Georgiacetus, the Georgia Whale. See Georgiacetus (Section 10) and the Basilosaurids (Section 11) on this site.

Research by Dr. Mark Uhen, the leading expert in Eocene and Oligocene whales, suggests that all modern whales are descended through Georgiacetus (8).

By the very end of the Eocene, the earliest cold-adapted whales had emerged. Their fossils are known from Antarctica. See Llanocetus denticrenatus, (Section 11) the oldest known baleen whale whose fossils were found in Antarctica.

The glaciation event which occurred at end of the Eocene would have ended whales if cold adapted species hadn't emerged at the poles. It did end the basilosaurids, but their polar decedents survived.

The climate cooled dramatically and coastlines fell far below modern levels as glaciers spread from the poles. The Coastal Plain sea was drained when the glaciers reached their peak, and our coastline retreated all the way to the Continental Shelf.

The Eocene ended in the ice of the Grand Coupure and Oligocene Epoch opened when the world warmed again, the ice retreated, and sea levels rose dramatically. New species had an opportunity to become established. Older, cold-tolerant species, expanded their ranges.

Understanding These Deposits.

As early as 1911 geologists Otto Veatch with the Georgia Geologic Survey and Lloyd William Stephenson with the USGS included these sediments in their famous survey of the Coastal Plain. Veatch and Stephenson looked at everything, from the paleontology of the Coastal Plain to its mineral and natural resource wealth.

This survey was done at the request of Samuel W. McCallie; the adventuresome Georgia State Geologist from 1908 to 1933. The 1911 survey served Georgia very well, revealing wealth that supported a century's worth of mining operations, uncounted jobs, and carried us through two world wars.

Veatch & Stephenson filed this 1911 report on these deposits. (7)

Elko, Houston County.-There is a well-known occurrence of flint (chert) in the railroad cuts one mile south of Elko. The flint appears as massive fragments of compact jasper, breaking with a sharp, splintery, conchoidal fracture, and also as friable, very fossiliferous masses in red clay.

The locality is of interest as the flint and clay may be of economic value for road material. At Taylors Ford, four miles south of Elko, on the Unadilla road, fossiliferous flint fragments embedded in red and yellow clay are prominently exposed.

A collection of Vicksburg (Early Oligocene) fossils was made near this locality by Samuel W. McCallie.

In 1935 this fossiliferous chert suspended in red clay was studied as The Flint River Formation by C. W. Cooke.

F. S. McNeil looked at it in 1947 and H. E. LaGrand studied it again in 1962; but none of these researchers correctly recognized the stratigraphy of the area.

In 1970 Sam Pickering was the first geologist to understand the sequence of and age of these Houston County fossils.

This tour is primarily based on Pickering's research and field observations from 45 years ago.(1)

Pickering went on to do a tour as Georgia State Geologist from 1972 to 1978 and lead the 1976 project to create the Geologic Map of Georgia. The previous map had been created in 1937.

Pickering also used The Flint River Formation to describe these sediments. That has since been abandoned since there is no bedding for these deposits. They’re not in their original positions; they’re the bones of reefs dissolved long before any hominids ever walked planet Earth.

Pickering correctly recognized that both Early and Late Oligocene fossils were intermingled and suspended in variable sandy clay; typically red clay. The red clay was younger than the fossils it contained. The fossils are recorded in chert, which is hardened limestone originally laid down as reefs.

This limestone originally formed on the sea floor.

Sea levels fell. Silica rich, slightly acidic groundwater inundated the limestone and slowly began dissolving it. Even the mild acid of lemonade can dissolve limestone.

Natural cavities slowly become caves. Cave ceilings collapsed forming sinkholes at the surface.

Some of the limestone eluded acidic groundwater and absorbed the water’s silica which, over time, hardened the limestone into the tough chert we’re collecting.

Chert does not dissolve in acidic water; it is very tough and resistant to both nature and careless hands.

The chert fossils we’ll find are all that remains from at least two distinct episodes of Oligocene Epoch high sea level stands and reef building on Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

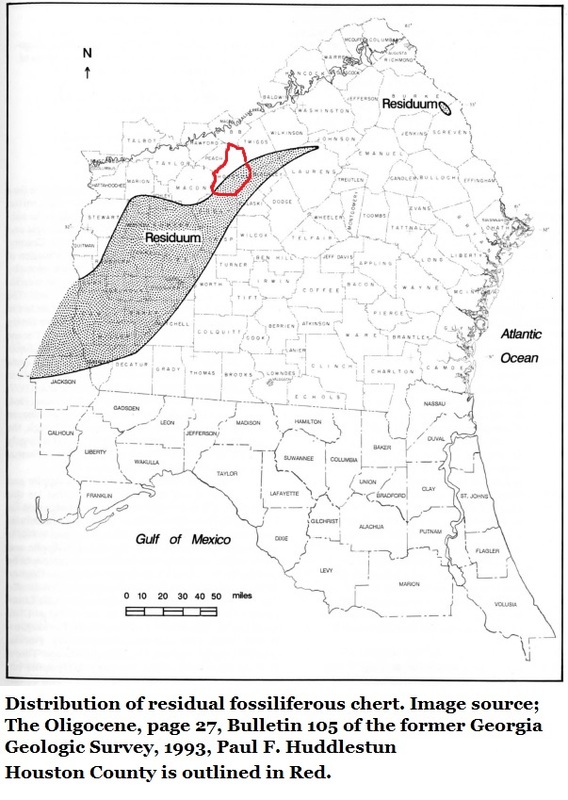

In Georgia’s geologic literature the material you're collecting is referred to as Oligocene Undifferentiated Residuum; an accurate if not very romantic name assigned by Paul F. Huddlestun in 1993. (3)

In its many forms chert can be very colorful and attractive; chalcedony, agate, and jasper are all forms of chert. It is a favorite material for the lapidary arts. Observe its variable textures and colors while in the field.

Chert was the preferred local material Native Americans used for their projectile points and tools throughout their long history in Georgia. Artifacts created from local chert will frequently have little geode pockets of crystals in them, as do many of these fossils you'll find. Crystals such as those seen in the images above.

One million years

It is easy to get lost in the depths of geologic time.

The youngest material we’ll collect today formed more than 23 million years ago. That's a big hunk of time so let's start with one million years ago.

If we broke that down into a timeline, where each year was represented by one inch, our 1 million year timeline would be 15.78 miles long.

To offer a sense of perspective:

It is easy to get lost in the depths of geologic time.

The youngest material we’ll collect today formed more than 23 million years ago. That's a big hunk of time so let's start with one million years ago.

If we broke that down into a timeline, where each year was represented by one inch, our 1 million year timeline would be 15.78 miles long.

To offer a sense of perspective:

- Americans landed on the moon in 1969. More than 3 feet back on our timeline.

- In 1733 the first English settlers landed in what would become Savannah with a royal charter to establish the Province of Georgia. This is less than 23.5 feet back on our timeline.

- Written language began sometime around 6,000 years ago; or 500 feet back on our timeline.

- Our species emerged about 200,000 years ago or 3.16 miles back on our timeline.

- The youngest Oligocene fossils on this tour lived 23.3 million years ago, or 367 miles back on our timeline.

References

1. Stratigraphy, Paleontology, And Economic Geology of Portions Of Perr and Cochran Quadrangles, Georgia; by Sam M. Pickering Jr., Bulletin 81, The Georgia Geologic Survey, 1970

2. Geologic Atlas of the Fort Valley Area; by John H. Hetrick, Geologic Atlas 7, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1990

3. The Oligocene; A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; By Paul F. Huddlestun, Bulletin 105, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1993

4. GeorgiasFossils.com, Section 3, Geologic Time, By Thomas Thurman

5. Line Drawings; Artist Carl Vardaman, 1970

6. The Phanerozoic Record of Global Sea-Level Change; by Kenneth G. Miller, Michelle A. Kominz, James V. Browning, James D. Wright, Gregory S. Mountain, Miriam E. Katz, Peter J. Sugarman, Benjamin S. Cramer, Nicholas Christie-Blick, Stephen F. Pekar, sciencemag.org, Science 310, 25 Nov 2005

7. Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, A preliminary Report, Bulletin 26, Otto Veatch & Lloyd William Stephenson, Prepared in Co-Operation with the USGS; 1911

8. Georgiacetus vogtlensis

New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.