Revised

19A; Two Small Primitive Horses

for Taylor County Move the Science of Georgia Geology Forward

By Thomas Thurman

01/Dec/2020

Reynolds, Georgia has cool fossils.

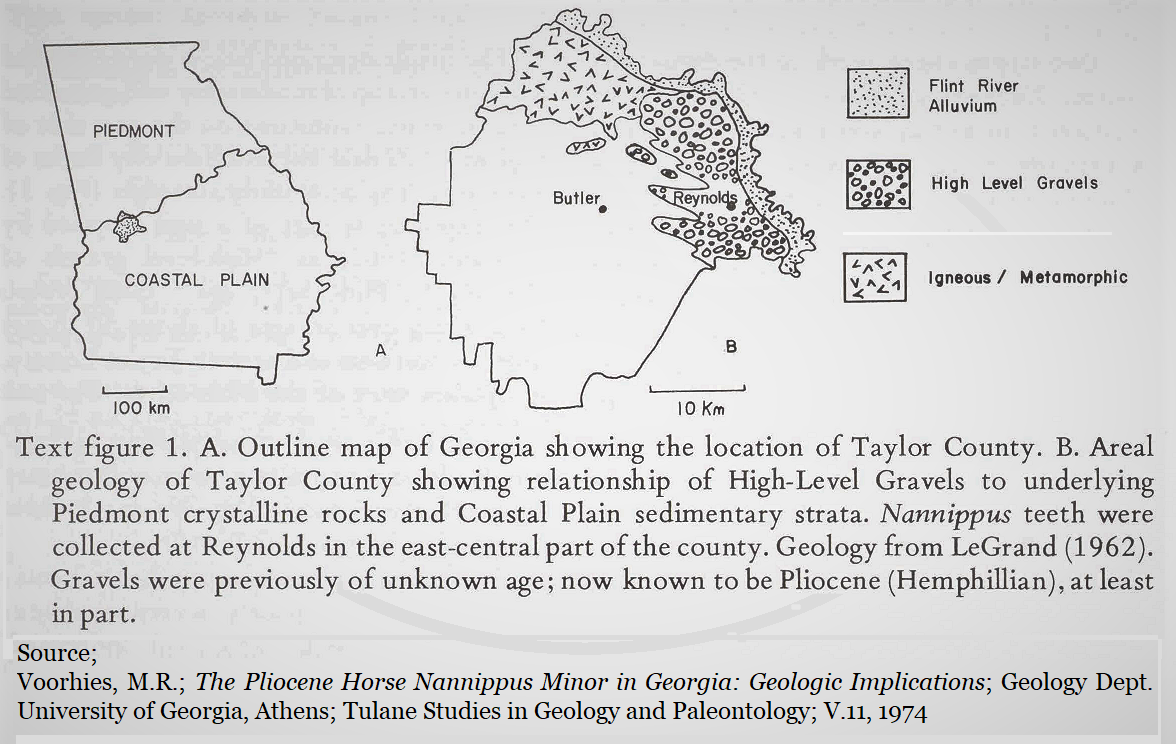

Taylor County straddles Georgia’s Fall Line. On the eastern side you’ll find the city of Reynolds which has produced scientifically important fossils which helped answer one of the mysteries in Georgia’s geologic history. They speak of a plain, populated by multiple species of horses, which endured a flood.

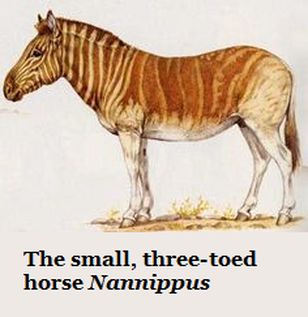

A Small Three-Toed Horse

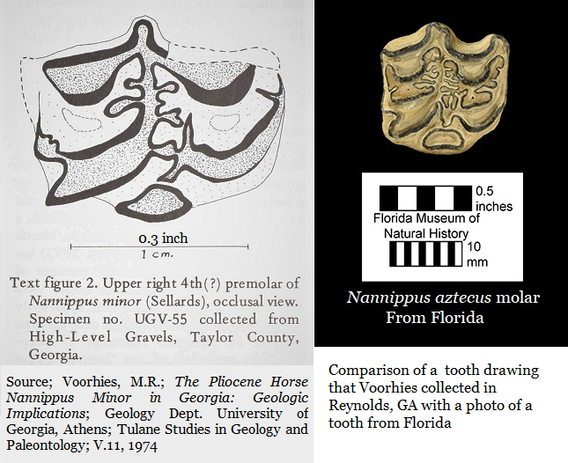

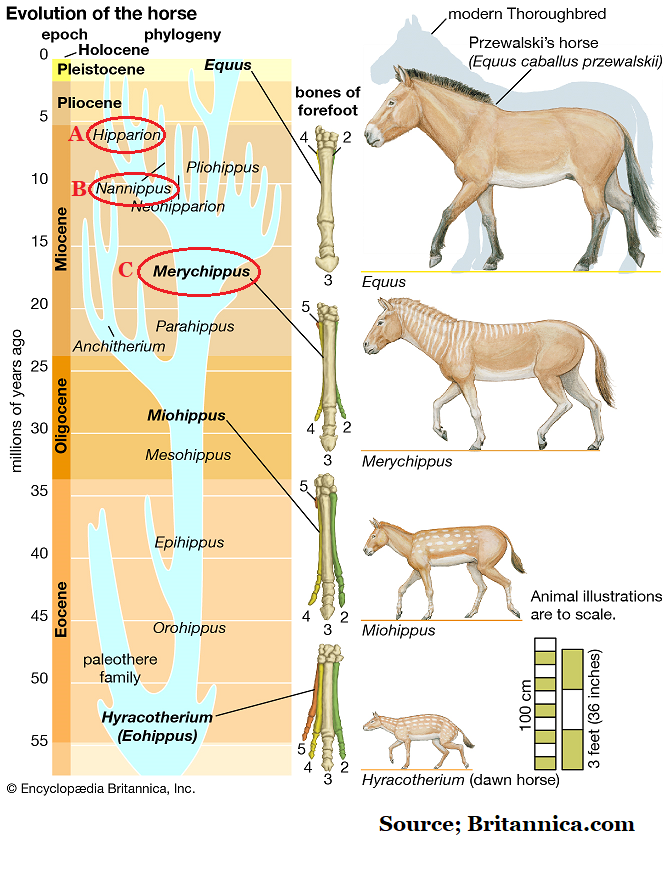

In 1974 Michael Voorhies, Professor of Paleontology at the University of Georgia, found and reported two molars in a deposit within the city limits of Reynolds, Georgia. He identified them as belonging to the small, three-toed horse Nannippus minor. He assigned the larger one as UGV-55 & the smaller one as UGV-56.

Both were worn and damaged, but neither was in bad shape. There are no known photos of either but Voorhies provided good measurements and descriptions. Because of the size difference he suspected the molars represented two separate individuals, the fact that they had wear differences reinforced this opinion. (1)

The Nannippus genus of primitive horses ranged from 65 kilos to 90 kilos (143lbs to 200lbs). Modern horses weigh between 380 kilos to 550 kilos (840lbs to 1,210 lbs).

Dr. Richard Hulbert, Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History explains that the species Nannippus minor has since been reassigned as Nannippus aztecus. (2) He knows the genus well since Florida has reported multiple fossils from several individuals.

The Nannippus genus of primitive horses ranged from 65 kilos to 90 kilos (143lbs to 200lbs). Modern horses weigh between 380 kilos to 550 kilos (840lbs to 1,210 lbs).

Dr. Richard Hulbert, Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History explains that the species Nannippus minor has since been reassigned as Nannippus aztecus. (2) He knows the genus well since Florida has reported multiple fossils from several individuals.

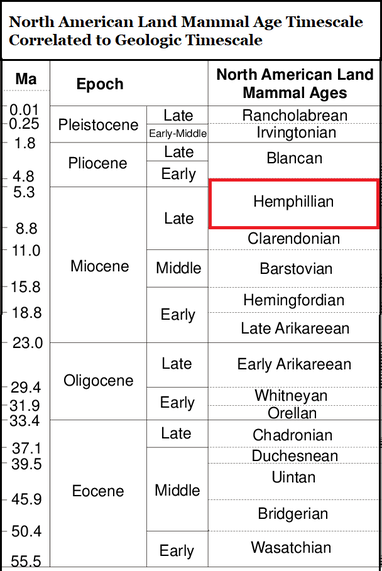

Dr. Hulbert has collected N. aztecus material in Florida. In a December 2020 email he explained that “the range for Nannippus aztecus is late Miocene to earliest Pliocene,” or NALMA Stage Hemphillian 2 to Hemphillian 4.

NALMA is the "North American Land Mammal Age" which is a timescale correlating the many species which have walked across North America though the geologic ages of mammals. It is the NALMA Hemphillian Stage is divided into four subintervals as seen below.

NALMA is the "North American Land Mammal Age" which is a timescale correlating the many species which have walked across North America though the geologic ages of mammals. It is the NALMA Hemphillian Stage is divided into four subintervals as seen below.

Early Hemphillian

Hh1 9.0 to 7.5 million years ago

Hh2 7.5 to 6.8 million years ago (Nannippus aztecus emerges)

Late Hemphillian

Hh3 6.8 to 5.7 million years ago

Hh4 5.7 to 4.75 million years ago (Nannippus aztecus extinct)

Hh1 9.0 to 7.5 million years ago

Hh2 7.5 to 6.8 million years ago (Nannippus aztecus emerges)

Late Hemphillian

Hh3 6.8 to 5.7 million years ago

Hh4 5.7 to 4.75 million years ago (Nannippus aztecus extinct)

A second species is recognized,

Pseudhipparion simpsoni

Hulbert reports that during the late 1980s UGA loaned him the teeth Voorhies had collected so he could review them. He saw that the larger of the two teeth, UCV-55, is indeed a molar from the Nannippus aztecus, but he also observed that the smaller tooth Voorhies recovered, UGV-56 is incorrectly identified as a N. aztecus, diagnostics suggest it is probably a Pseudhipparion simpsoni. However, the condition of the tooth prevents definite identification.

Pseudhipparion simpsoni is a small, 40 kilo (90 lb) primitive horse complete with three toes, significantly smaller than Nannippus.

There’s another important fact about the little Pseudhipparion simpsoni, its only known from the latest Hemphillian and is dated by the Palmetta Fauna of Central Florida to very Early Pliocene at 4.5 million years ago.

For the sake of understanding, let's assume Hulbert is right and the UGV-56 tooth is a Pseudhipparion simpsoni.

Hulbert completed his research & notes on the two teeth, returned them to UGA, and continued his work on the distribution of primitive horses.

Pseudhipparion simpsoni

Hulbert reports that during the late 1980s UGA loaned him the teeth Voorhies had collected so he could review them. He saw that the larger of the two teeth, UCV-55, is indeed a molar from the Nannippus aztecus, but he also observed that the smaller tooth Voorhies recovered, UGV-56 is incorrectly identified as a N. aztecus, diagnostics suggest it is probably a Pseudhipparion simpsoni. However, the condition of the tooth prevents definite identification.

Pseudhipparion simpsoni is a small, 40 kilo (90 lb) primitive horse complete with three toes, significantly smaller than Nannippus.

There’s another important fact about the little Pseudhipparion simpsoni, its only known from the latest Hemphillian and is dated by the Palmetta Fauna of Central Florida to very Early Pliocene at 4.5 million years ago.

For the sake of understanding, let's assume Hulbert is right and the UGV-56 tooth is a Pseudhipparion simpsoni.

Hulbert completed his research & notes on the two teeth, returned them to UGA, and continued his work on the distribution of primitive horses.

Voorhies

Voorhies placed the two teeth in the University of Georgia Geology Department Collection.

Sadly, despite many important discoveries UGA didn't retain the Vertebrate Paleontology Program when Voorhies left in the mid-1970s to teach in his native Nebraska. Subsequently the fossils he collected and identified have been lost, this seems to have happened during the late 1990s. (See section 20I of this website)

Voorhies placed the two teeth in the University of Georgia Geology Department Collection.

Sadly, despite many important discoveries UGA didn't retain the Vertebrate Paleontology Program when Voorhies left in the mid-1970s to teach in his native Nebraska. Subsequently the fossils he collected and identified have been lost, this seems to have happened during the late 1990s. (See section 20I of this website)

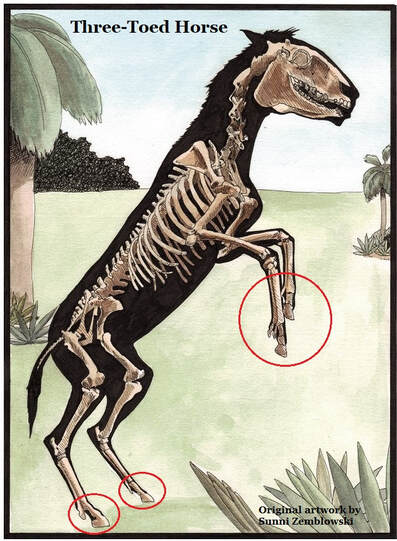

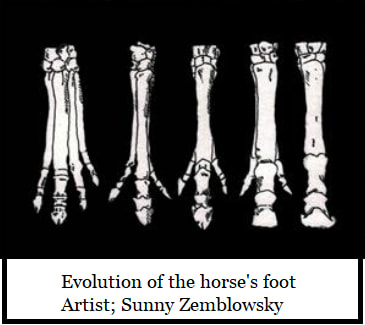

Modern horses (and ponies) walk on a single toe. So did both the genus Nannippus & Pseudhipparion. To additional toes were present on each leg they just didn’t quite reach the ground.

Below is an edited passage from Wikipedia giving a brief description of how and why horses evolved…

The early ancestors of the modern horse walked on several spread-out toes as an adaptation to life spent walking on the soft, moist grounds of forests. As grass species began to flourish diets shifted from foliage to grasses and this led to larger and more durable teeth.

At the same time the steppes began to appear and the horse's predecessors needed to outrun predators. This slowly led to the lengthening of limbs and the lifting of some toes from the ground so that the weight of the body was eventually placed on the longest third toe. (Source; Wikipedia; Evolution of the horse)

The early ancestors of the modern horse walked on several spread-out toes as an adaptation to life spent walking on the soft, moist grounds of forests. As grass species began to flourish diets shifted from foliage to grasses and this led to larger and more durable teeth.

At the same time the steppes began to appear and the horse's predecessors needed to outrun predators. This slowly led to the lengthening of limbs and the lifting of some toes from the ground so that the weight of the body was eventually placed on the longest third toe. (Source; Wikipedia; Evolution of the horse)

The Deposit

I'm curious as to what led Voorhies to Reynolds but there is no rational stated in his report. He does state "I wish to thank my wife, Jane, for help in collecting the fossils and in preparing the illustrations." That suggests they personally collected the fossils. But there is really nothing about Reynolds which suggest vertebrate fossils are present in the high-level gravels.

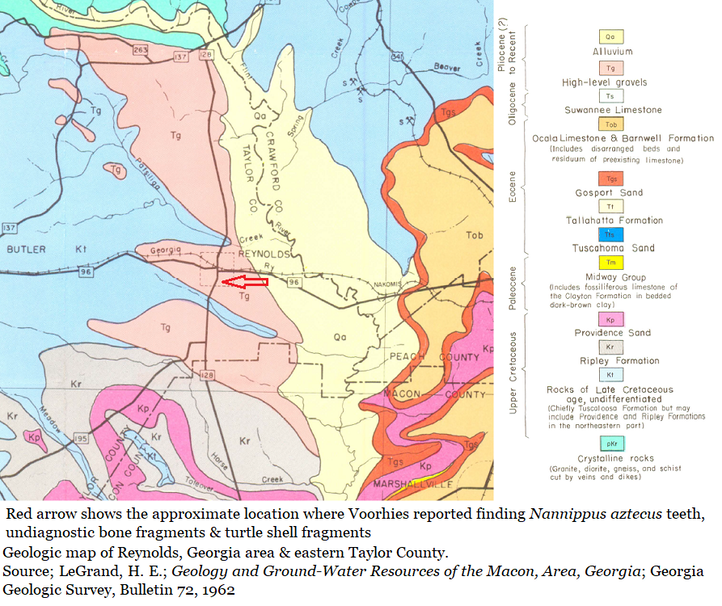

Voorhies reported the horse teeth as recovered from an exposure of moderately well cemented sandstone on the south side of Reynolds and east side of Highway 128 near the city limits. He additionally observed that the fossil bearing sediments occupied a “high topographic position”; they were uphill. He also reports on he presence of conglomerate in the sediments.

Naturally occurring conglomerate is rather rare on Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

I'm curious as to what led Voorhies to Reynolds but there is no rational stated in his report. He does state "I wish to thank my wife, Jane, for help in collecting the fossils and in preparing the illustrations." That suggests they personally collected the fossils. But there is really nothing about Reynolds which suggest vertebrate fossils are present in the high-level gravels.

Voorhies reported the horse teeth as recovered from an exposure of moderately well cemented sandstone on the south side of Reynolds and east side of Highway 128 near the city limits. He additionally observed that the fossil bearing sediments occupied a “high topographic position”; they were uphill. He also reports on he presence of conglomerate in the sediments.

Naturally occurring conglomerate is rather rare on Georgia’s Coastal Plain.

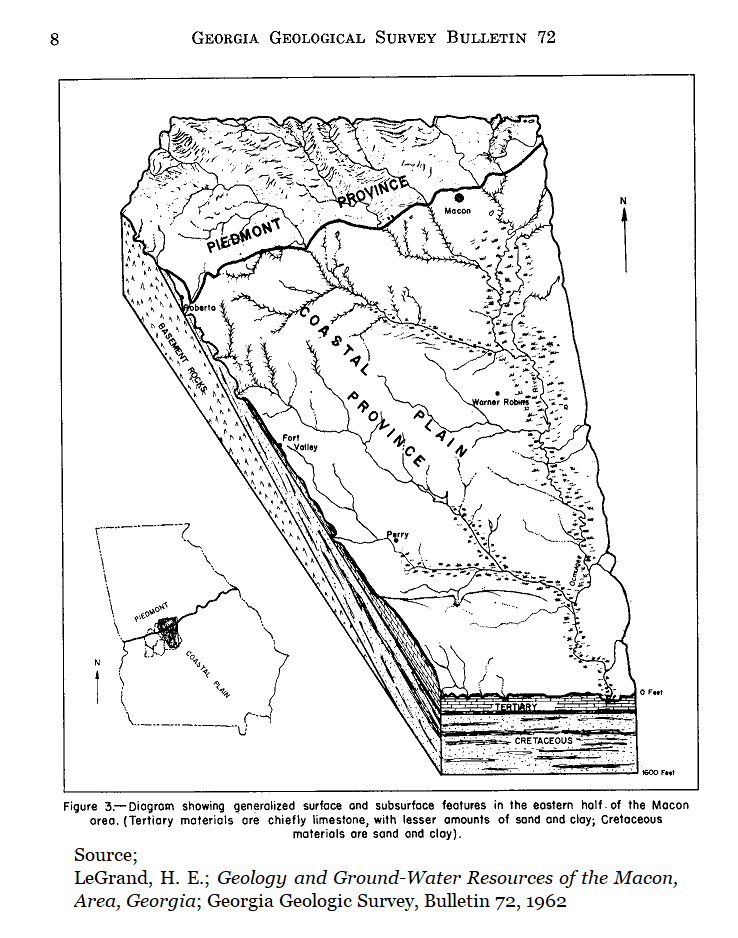

This area was surveyed in 1962 by H. E. LeGrand of the Georgia Geologic Survey who observed the high-level gravels that formed a cap over an area of about 50 square miles in northern and eastern Taylor County, the gravels occur at the highest elevations. The local terrain is gently hilly.

LeGrand reported fossils in the area, but in the lowlands of the waterways. He certainly suggested that the high-level gravels were Pliocene, but he doesn't offer evidence.

Voorhies reported that the conglomerate sandstone is part of the high-level gravels. LeGrand doesn't mention conglomerate in his report.

LeGrand reported fossils in the area, but in the lowlands of the waterways. He certainly suggested that the high-level gravels were Pliocene, but he doesn't offer evidence.

Voorhies reported that the conglomerate sandstone is part of the high-level gravels. LeGrand doesn't mention conglomerate in his report.

The presence of the conglomerate was confirmed in December 2020 by fieldwork, but it was very limited. The only two small samples of the conglomerate collected are shown here, no more was even seen. Highway 128 had been recently re-paved and the area probably further developed over the last 58 years. Hopefully this conglomerate occurs elsewhere in the area.

The conglomerate was found roadside on an uphill lane on the east side of Hwy 128 just within the city limits. Just where Voorhies described. But the properties here are yards and only a bit of conglomerate rubble was found loose on the side of the road.

The conglomerate was found roadside on an uphill lane on the east side of Hwy 128 just within the city limits. Just where Voorhies described. But the properties here are yards and only a bit of conglomerate rubble was found loose on the side of the road.

Voorhies’ record;

“At the productive exposure the strata may be described as a poorly sorted sandstone interbedded with lenses of polymictic conglomerate, the clasts in which are composed of quartz, chert, and claystone. (Polymictic simply means several minerals are present in the conglomerate, as seen in the pics.) It was in one of these lenses that the vertebrate fossils were found. Some of the bone fragments were badly abraded but the two horse teeth were fairly well preserved.”

“At the productive exposure the strata may be described as a poorly sorted sandstone interbedded with lenses of polymictic conglomerate, the clasts in which are composed of quartz, chert, and claystone. (Polymictic simply means several minerals are present in the conglomerate, as seen in the pics.) It was in one of these lenses that the vertebrate fossils were found. Some of the bone fragments were badly abraded but the two horse teeth were fairly well preserved.”

That description quoted from Voorhies tells us that not only were teeth present, but abraded bones which seemingly couldn’t be confidently identified. He additionally mentions undiagnostic turtle material in another passage. The description seems to say that the fossils are found in the sandstone which also holds lenses of the conglomerate.

The Local Stratigraphy & Fossil Beds, LeGrand 1962

Upland Gravels (High level gravels)

In 1962 LeGrand suspected the upland gravels were Pliocene in age. He reports (4,pg33) unsorted gravel and sandy clay of probable Pliocene age overlying the Cretaceous and Tertiary deposits in the interstream areas and Pleistocene alluvial deposits border major streams. Alluvial meaning deposits left by flowing water.

Residuum

A flat area about 3 miles south of Butler at an altitude of about 620 feet above sea level may be residuum from limestone of Eocene age. This area is underlain by fertile red clay rich soil upon which are several sinkholes. The surface is possibly high enough to be an outlying updip extension of the Tivola Limestone at Rich Hill in Crawford County.

Providence Sand

Appro. 67 million years old. (Middle Maastrichtian) (Ref#4&5)

Caps the hills in the southern part of Taylor County & probably occurs on the divide north and west of Butler, although it is indistinguishable from the underlying Cretaceous deposits.

Ripley Formation

Appro. 69 million years old (Lower Maastrichtian) (Ref#4&5)

Fine yellow sand interbedded with yellow clay & white kaolin. The Ripley occurs in the southern part of (Taylor) county. Beds of black clay containing plant remains occur locally, but in outcrops exposed for any length of time the black clay becomes bleached and resembles white kaolin. One of the fossil-plant localities is on the south side of Whitewater Creek on the old road to Charing, 6 miles SW of Butler. Another occurs near a stream crossing 2 miles SW of Reynolds.

Tuscaloosa Formation

Appro. 94 million years old (Upper Cenomanian) (Ref#4&5)

Poorly bedded white kaolin, light colored sand & sandy clay.

Upland Gravels (High level gravels)

In 1962 LeGrand suspected the upland gravels were Pliocene in age. He reports (4,pg33) unsorted gravel and sandy clay of probable Pliocene age overlying the Cretaceous and Tertiary deposits in the interstream areas and Pleistocene alluvial deposits border major streams. Alluvial meaning deposits left by flowing water.

Residuum

A flat area about 3 miles south of Butler at an altitude of about 620 feet above sea level may be residuum from limestone of Eocene age. This area is underlain by fertile red clay rich soil upon which are several sinkholes. The surface is possibly high enough to be an outlying updip extension of the Tivola Limestone at Rich Hill in Crawford County.

Providence Sand

Appro. 67 million years old. (Middle Maastrichtian) (Ref#4&5)

Caps the hills in the southern part of Taylor County & probably occurs on the divide north and west of Butler, although it is indistinguishable from the underlying Cretaceous deposits.

Ripley Formation

Appro. 69 million years old (Lower Maastrichtian) (Ref#4&5)

Fine yellow sand interbedded with yellow clay & white kaolin. The Ripley occurs in the southern part of (Taylor) county. Beds of black clay containing plant remains occur locally, but in outcrops exposed for any length of time the black clay becomes bleached and resembles white kaolin. One of the fossil-plant localities is on the south side of Whitewater Creek on the old road to Charing, 6 miles SW of Butler. Another occurs near a stream crossing 2 miles SW of Reynolds.

Tuscaloosa Formation

Appro. 94 million years old (Upper Cenomanian) (Ref#4&5)

Poorly bedded white kaolin, light colored sand & sandy clay.

Mystery of the Peneplain

Georgia is old. Three hundred million years ago the Appalachian Mountains were mighty and freshly risen, standing as far south as modern Georgia’s Fall Line and coastal plain. Eons have worn the fall line mountains to hills.

The evidence of these lost mountains is found in the rounded quartz rocks which are so common on the northern coastal plain. Deep in those lost mountains quartz formed when magma cooled. Just as Stone Mountain formed further north near Atlanta.

“Like water turning into ice, silicon dioxide will crystallize into quartz as it cools. Slow cooling generally allows the crystals to grow larger. Quartz that grows from silica-rich water forms in a similar way.” (International Gem Society)

The quartz was exposed by erosion and then weathered out. The crystals were transported, rolled down the side of a mountain or along the bed of a creek, or river, repeatedly bumping into each other for long periods.

Sometimes mountains collapsed, crushing the quartz and pressing shattered crystals into new shapes. Erosion continued and even these were exposed and transported. This natural tumbling rounded rocks into pebbles and ground many to sand.

This is the source of the naturally occurring gravel seen in many areas of the coastal plain. Mountains that had weathered away and waters which tumbled the rocks along until they were gravel and sand.

So there are many places in Taylor County, even in Reynolds, where these rounded pebbles are found on hilltops. So…exactly how does nature get a pebble, rounded by a river or creek, on a hilltop?

In this case, that’s what “high-level gravel” means. Rounded pebbles suspended in clay and sand cresting a hill or ridge.

It was part of a peneplain. A peneplain is an erosional feature. Of course, repeated sea level changes were intimately involved but when you erode mountains all that material must go somewhere. Water naturally spread those mountains across the coastal plain like peanut butter on a slice of bread. Sand, clay & gravels acted as a blanket of debris.

When sea levels retreated our ancient rivers and creeks slowly found their paths again across the peneplain and gradually cut new valleys into it until they were again following deeper, old river and creek beds.

All of this was well known in 1962 & 1974, but no one was sure when the peneplain and its high-level gravels had formed.

Georgia is old. Three hundred million years ago the Appalachian Mountains were mighty and freshly risen, standing as far south as modern Georgia’s Fall Line and coastal plain. Eons have worn the fall line mountains to hills.

The evidence of these lost mountains is found in the rounded quartz rocks which are so common on the northern coastal plain. Deep in those lost mountains quartz formed when magma cooled. Just as Stone Mountain formed further north near Atlanta.

“Like water turning into ice, silicon dioxide will crystallize into quartz as it cools. Slow cooling generally allows the crystals to grow larger. Quartz that grows from silica-rich water forms in a similar way.” (International Gem Society)

The quartz was exposed by erosion and then weathered out. The crystals were transported, rolled down the side of a mountain or along the bed of a creek, or river, repeatedly bumping into each other for long periods.

Sometimes mountains collapsed, crushing the quartz and pressing shattered crystals into new shapes. Erosion continued and even these were exposed and transported. This natural tumbling rounded rocks into pebbles and ground many to sand.

This is the source of the naturally occurring gravel seen in many areas of the coastal plain. Mountains that had weathered away and waters which tumbled the rocks along until they were gravel and sand.

So there are many places in Taylor County, even in Reynolds, where these rounded pebbles are found on hilltops. So…exactly how does nature get a pebble, rounded by a river or creek, on a hilltop?

In this case, that’s what “high-level gravel” means. Rounded pebbles suspended in clay and sand cresting a hill or ridge.

It was part of a peneplain. A peneplain is an erosional feature. Of course, repeated sea level changes were intimately involved but when you erode mountains all that material must go somewhere. Water naturally spread those mountains across the coastal plain like peanut butter on a slice of bread. Sand, clay & gravels acted as a blanket of debris.

When sea levels retreated our ancient rivers and creeks slowly found their paths again across the peneplain and gradually cut new valleys into it until they were again following deeper, old river and creek beds.

All of this was well known in 1962 & 1974, but no one was sure when the peneplain and its high-level gravels had formed.

What the fossils tell us.

LeGrand suspected the upland gravels had formed during Pliocene, 5.3 to 2.5 million years ago, but he had no evidence.

Voorhies found some evidence. The little species of three-toed horse Nannippus aztecus only walked the Earth from 4.75 to 7.50 million years ago. From the Late Miocene to the Early Pliocene.

Hulbert possibly gave us an excellent date, assuming that worn tooth is from a Pseudhipparion simpsoni that narrows our timeline dramatically to 4.5 million years ago. (6) This, in turn, suggests the peneplain formed about 4.5 million years ago.

LeGrand suspected the upland gravels had formed during Pliocene, 5.3 to 2.5 million years ago, but he had no evidence.

Voorhies found some evidence. The little species of three-toed horse Nannippus aztecus only walked the Earth from 4.75 to 7.50 million years ago. From the Late Miocene to the Early Pliocene.

Hulbert possibly gave us an excellent date, assuming that worn tooth is from a Pseudhipparion simpsoni that narrows our timeline dramatically to 4.5 million years ago. (6) This, in turn, suggests the peneplain formed about 4.5 million years ago.

Of course, when I visited Reynolds the two things I found beyond the conglomerate samples were artifacts, not fossils. A shard of native American pottery & a scraper with a broken tip.

Richard Hulbert's suspicions need to be confirmed. But he's in central Florida. Voorhies is retired in Nebraska. So that leaves Georgia amateurs and professionals to the work at hand, and Georgia's amateurs are up to the task.

Another outcrop of that conglomerate bearing Taylor County sandstone needs to be found. If we can locate more teeth & bones, we might can confirm Hulbert's diagnosis and dating.

Richard Hulbert's suspicions need to be confirmed. But he's in central Florida. Voorhies is retired in Nebraska. So that leaves Georgia amateurs and professionals to the work at hand, and Georgia's amateurs are up to the task.

Another outcrop of that conglomerate bearing Taylor County sandstone needs to be found. If we can locate more teeth & bones, we might can confirm Hulbert's diagnosis and dating.

Thanks PAG

A word of thanks to the Paleontology Association of Georgia, specifically President Hank Josey and Treasurer Ashley Quinn for their Resource page where these papers can be found.

RESOURCES | paleoassocga (wixsite.com)

A word of thanks to the Paleontology Association of Georgia, specifically President Hank Josey and Treasurer Ashley Quinn for their Resource page where these papers can be found.

RESOURCES | paleoassocga (wixsite.com)

References

- Voorhies, M.R.; The Pliocene Horse Nannippus Minor in Georgia: Geologic Implications; Geology Dept. University of Georgia, Athens; Tulane Studies in Geology and Paleontology; V.11, 1974

- Hulbert, Richard C. Jr. “The Range for Nannippus aztecus is late Miocene to earliest Pliocene (Hemphillian 2 to Hemphillian 4). The species name Nannippus minor is technically invalid and had to be replaced by N. aztecus.” Personal email, 01/Dec/2020

- LeGrand, H. E.; Geology and Ground-Water Resources of the Macon, Area, Georgia; Georgia Geologic Survey, Bulletin 72, 1962

- Rienhardt, Juergen; Thomas G. Gibson; Bybell, Laurel M.; Edwards, Lucy E.; Fredericksen, Norman O.; Sohl, Norman F.; Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Geology of the Chattahoochee River Valley, Western Georgia and Eastern Alabama. Excursions into Southeastern Geology II, Geological Society of America Field Trip 1980

- International Stratigraphic Chart, International Commission of Stratigraphy 2008

- Hulbert, Richard C., Jr.; Czaplewski, Nicholas J., & Webb, S. David; New Record of Pseudhipparion simpsoni (Mammalia, Equidae) From The Late Hemphillian of Oklahoma and Florida; Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 25(3), Pgs 737-740, September 2005