7H: Deinosuchus schwimmeri

In Recognition of

Earth Scientist & Paleontologist

Dr. David R. Schwimmer

Of Columbus State University

By Thomas Thurman

08/March/2022

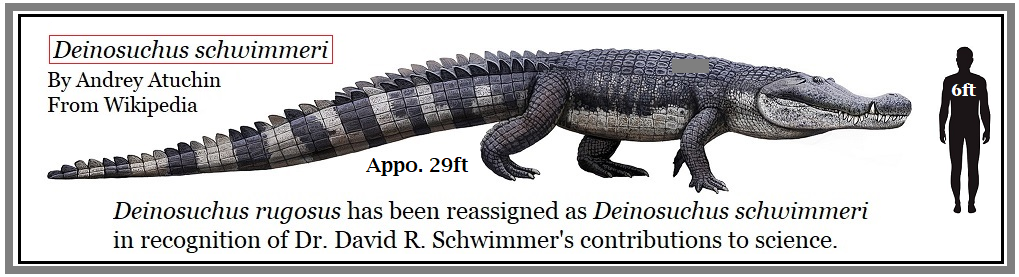

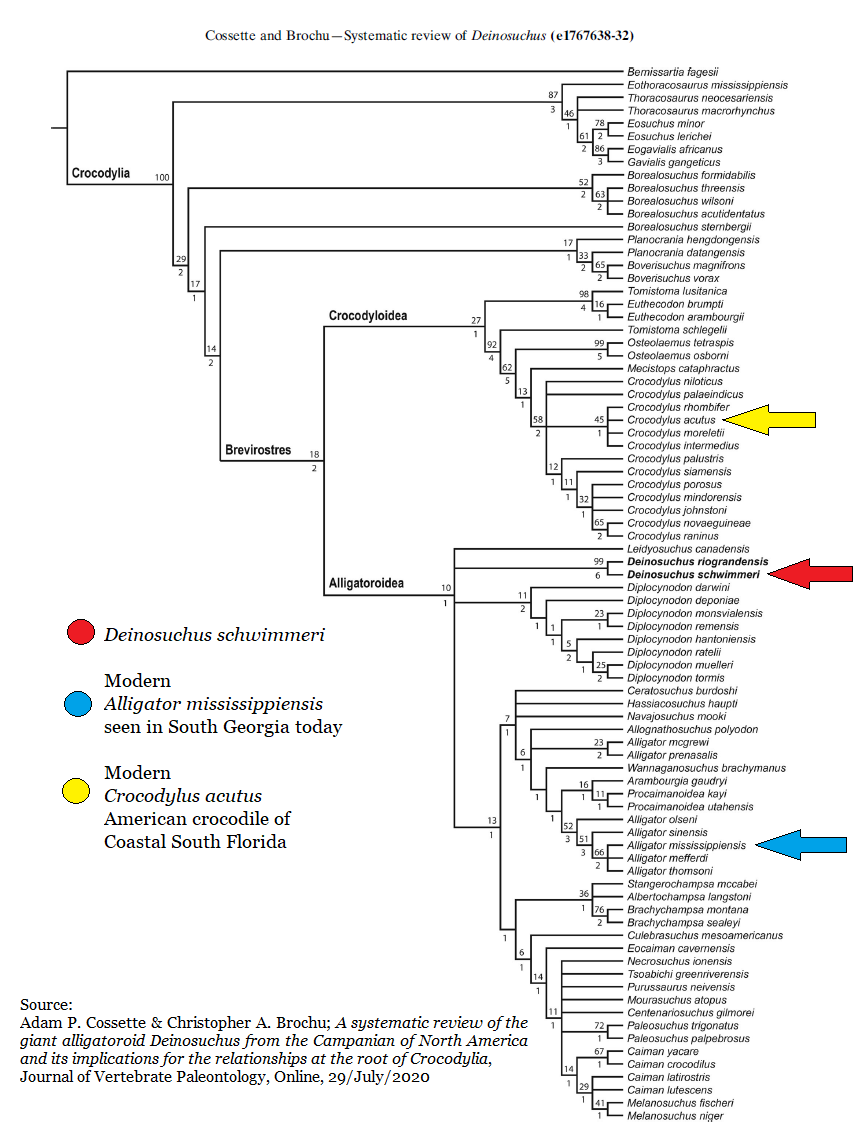

The giant Cretaceous crocodile Deinosuchus rugosa has been overturned. In a 2020 paper by Adam Cossette & Christopher Brochu, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, all eastern occurrences of the Deinosuchus are reassigned as Deinosuchus schwimmeri, in honor of our own Dr. David R. Schwimmer.

The ultimate reward for a scientist is to have their name preserved by their peers. You spend decades faithfully doing your bit, others notice, and if you're a paleontologist they write your name among the fossils which record the history of life on Earth.

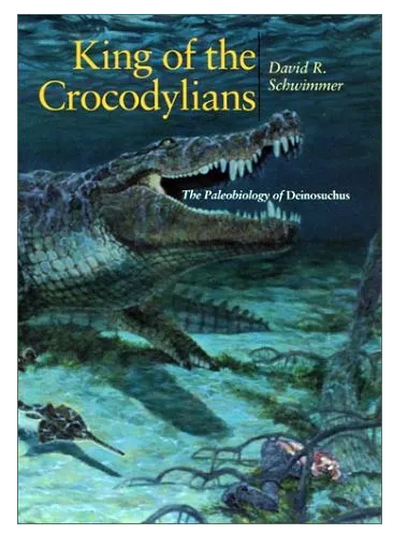

As the video clip below shows, Dr. Schwimmer not only knows a great deal about Deinosuchus, he's also passionate about researching the animal.

The Paper

Dr. Adam P. Cossette of New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Arkansas and Professor Christopher A. Brochu from the University of Iowa produced a significant paper; “A Systematic Review of the Giant Alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Campanian of North America and its Implications for the Relationships at the Root of Crocodylia”.

Deinosuchus was a giant. A 30-plus foot, dinosaur eating croc which lived 80 million years ago. That’s the laymen version of the wonderful opening line for Cossette and Brochu’s paper. The actual passage reads “Deinosuchus is a lineage of giant (≥10 m) Late Cretaceous crocodylians from North America. These were the largest semiaquatic predators in their environments and are known to have fed on large vertebrates, including contemporaneous terrestrial vertebrates such as dinosaurs.”

That's an epic first passage for an academic research paper. It continues; “Additionally, Deinosuchus rugosus is based on a holotype that is not diagnostic, and a new species, Deinosuchus schwimmeri, is named to encompass some specimens formerly assigned to D. rugosus.

To further quote the Cossette and Brochu over the naming of this species “…The specific epithet is named in honor of David R. Schwimmer for his tireless work on the Late Cretaceous paleontology of the Southeast and Eastern Seaboard, U.S.A.”

The Work of Schwimmer

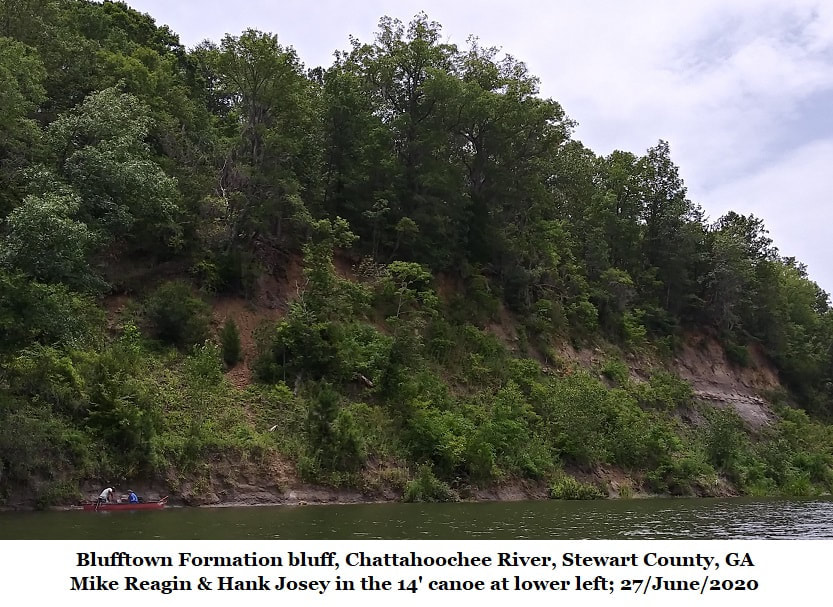

Sir Charles Lyell, the Father of Modern Geology, visited the USA twice and both times he did field research in Georgia. It was Lyell who recognized Cretaceous deposits in west Georgia’s Chattahoochee River Valley. It was field research by David Schwimmer that revealed Georgia’s Cretaceous deposits held both dinosaurs and the predator that sometimes fed on them.

Sir Charles Lyell, the Father of Modern Geology, visited the USA twice and both times he did field research in Georgia. It was Lyell who recognized Cretaceous deposits in west Georgia’s Chattahoochee River Valley. It was field research by David Schwimmer that revealed Georgia’s Cretaceous deposits held both dinosaurs and the predator that sometimes fed on them.

There are those who dismiss southeastern paleontology as irrelevant. One respected former Southeastern museum director spurned exploring the “jungles of the Southeast” and eagerly departed for the barren exposures westward.

That's okay, not everyone is cut out for Southeastern paleontology, it's a different kind of research occurring at river bluffs, ravines, weathered hilltops, road cuts, and creek banks. In exposures which might be 100 meters (320 feet) or 15 centimeters (6 inches) thick.

This is where the science is. These are the places where Dr. David Schwimmer of Columbus State University earns his reputation, in the field collecting the fossils which make his career. The jaw Schwimmer mentions in the video came from a riverbank exposure very similar to the one seen below.

Schwimmer studies Georgia's Cambrian trilobites and sponges, Cretaceous dinosaurs, giant crocs, pterosaurs, turtles, and uncounted shark teeth. Even a Pleistocene mastodon. Schwimmer continues to teach us many things about these fossils of west and north Georgia.

Twice now, he's been honored by having his named placed in the book of life on Earth, by having a species named for him.

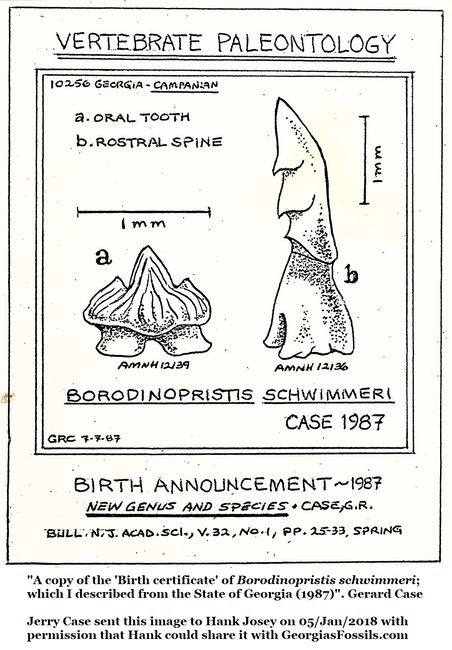

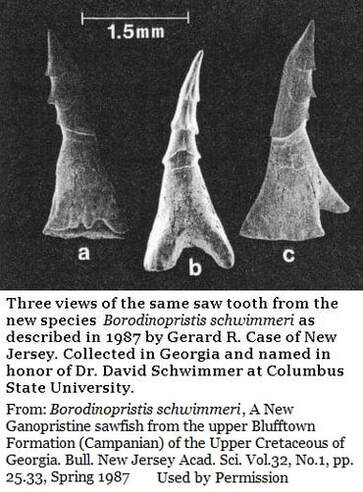

The first time was by Gerard (Jerry) Case. Jerry Case was an advanced amateur with an abiding interest in sharks, Schwimmer collaborated with Case on a paper over Cretaceous shark teeth.

In appreciation, and in 1987 Jerry Case late named a Late Cretaceous sawfish for David Schwimmer; Borodinopristis schwimmeri.

But this one is a little different. Cossette and Brochu are professional paleontologists and professors, like Schwimmer himself. This is recognition by your peers.

The authors observe; “...Deinosuchus rugosus is based on a holotype that is not diagnostic, and a new species, Deinosuchus schwimmeri, is named to encompass some specimens formerly assigned to D. rugosus."

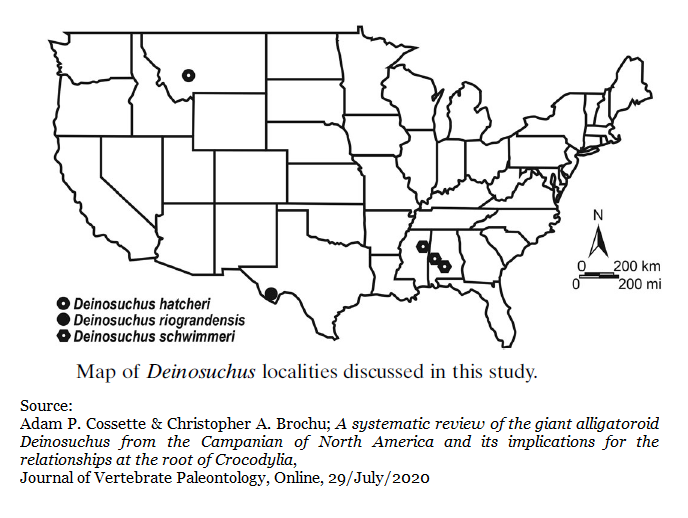

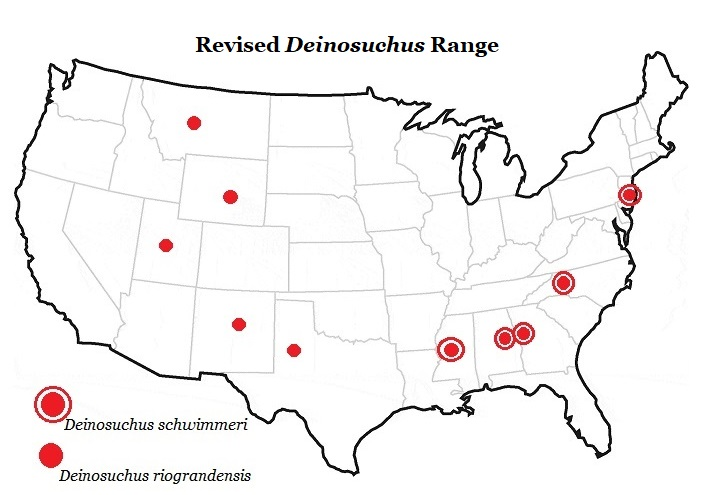

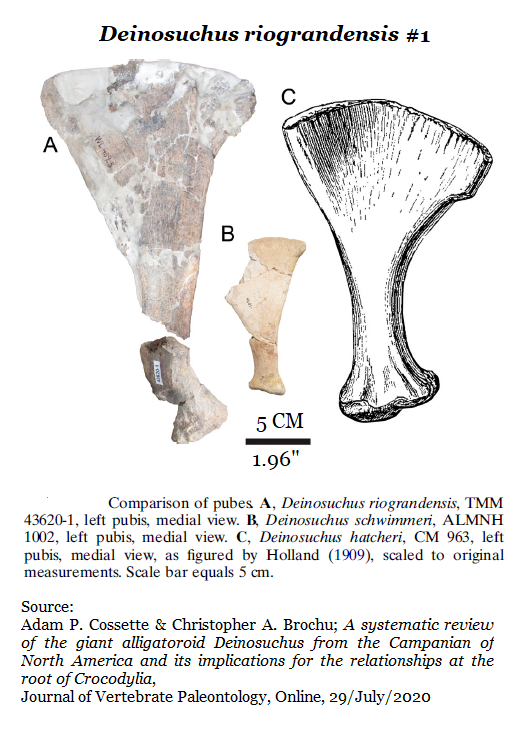

Cossette & Brochu argue, successfully, that the three established species of Deinosuchus should be collapsed into two species. That the current genus holotype, Deinosuchus hatcheri is extremely incomplete. Therefore, they collapse D. hatcheri and fold it into the western species, Deinosuchus riograndensis as the genus holotype.

All western occurrences of Deinosuchus are assigned as D. riograndensis and all eastern occurrences as Deinosuchus schwimmeri. Deinosuchus schwimmeri is the smaller but more numerous species and a moderately common fossil in east Georgia's Blufftown Formation.

Traditional Species

Deinosuchus hatcheri

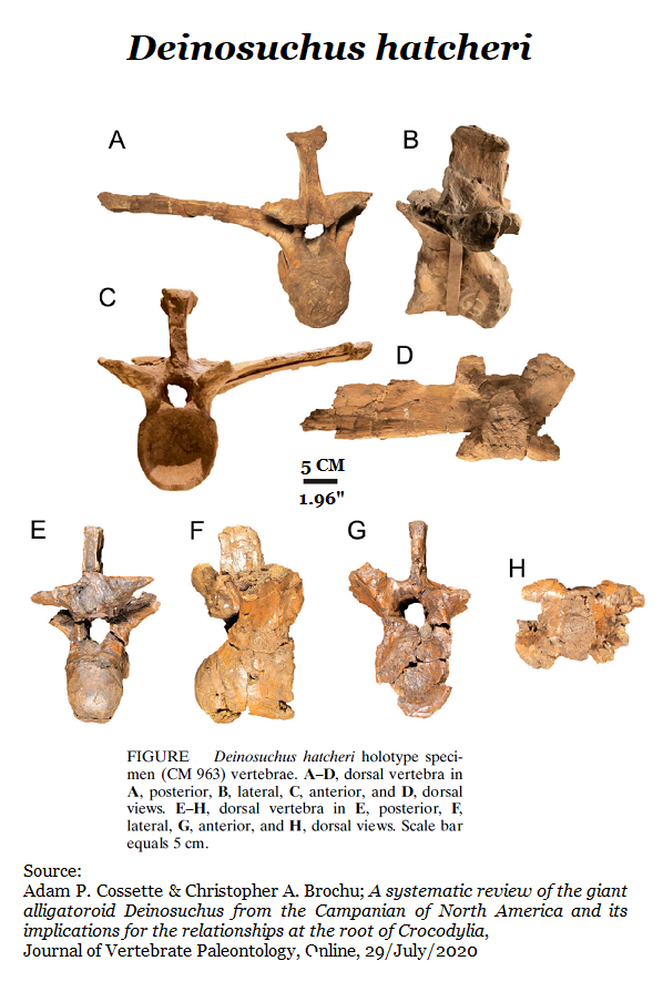

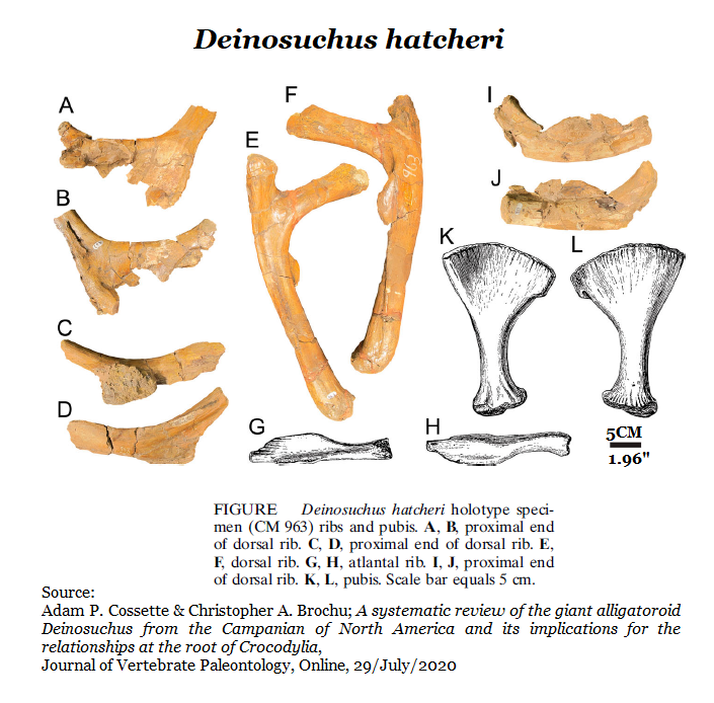

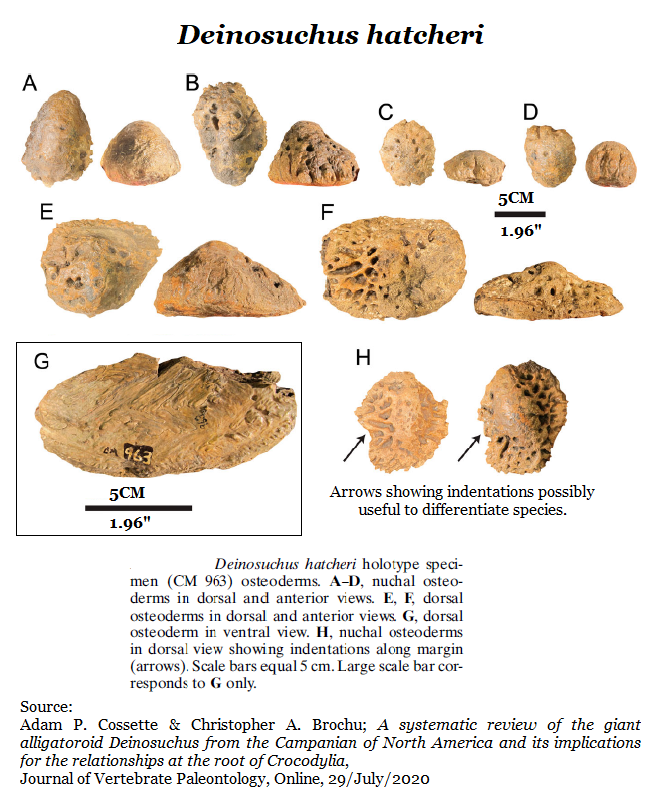

The generic name holder for the genus is Deinosuchus hatcheri was found in the Judith River Formation of Fergus County, Montana. The holotype specimen (CM936) is held at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. The first specimens are reported from North Carolina in the 1850s; genus & species were erected in 1909 by Reverend William Jacob Holland. Specimen CM936 is represented by two vertebrae, a pubis, one atlantal rib, one first dorsal rib, numerous osteoderms, and several hundred fragments of bones that cannot be identified to element.

(In this JVP paper the authors report that the atlantal rib, pubis, and most of the unidentified fragments have been lost.) Sadly, lost fossils for scientifically significant specimens is a recurring theme in paleontology, Carnegie Museum of Natural History is not a minor institution lacking funding. Institutions losing fossils is an issue which needs addressing! (See "Items of Interest" on this website "Collections and Stewardship of Georgias's Fossils".)

Deinosuchus hatcheri

The generic name holder for the genus is Deinosuchus hatcheri was found in the Judith River Formation of Fergus County, Montana. The holotype specimen (CM936) is held at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. The first specimens are reported from North Carolina in the 1850s; genus & species were erected in 1909 by Reverend William Jacob Holland. Specimen CM936 is represented by two vertebrae, a pubis, one atlantal rib, one first dorsal rib, numerous osteoderms, and several hundred fragments of bones that cannot be identified to element.

(In this JVP paper the authors report that the atlantal rib, pubis, and most of the unidentified fragments have been lost.) Sadly, lost fossils for scientifically significant specimens is a recurring theme in paleontology, Carnegie Museum of Natural History is not a minor institution lacking funding. Institutions losing fossils is an issue which needs addressing! (See "Items of Interest" on this website "Collections and Stewardship of Georgias's Fossils".)

The diagnostic features erected by Holland include

- Massive osteoderms with inflated keels

- A pubis that is straighter & less deeply excavated posteriorly than modern crocodilians. (JVP reports that the holotype pubis is now lost.)

- Dorsal most extent of neural spines are transversely broad

- Postzygapophyses lie nearly on the same plane as the transverse processes.

The authors compared remaining specimens, and illustrations of lost specimens, with both extinct and modern species. They note that the available fossil record and knowledge of croc morphology has increased dramatically since 1909.

They found that characteristics diagnosing D. hatcheri “are shared with other species of Deinosuchus, themselves diagnosed by features not preserved in the holotype of D. hatcheri. Specimens from Texas and the Western Interior localities bear massive, inflated dorsal osteoderms…” They go on to explain that specimens from Alabama & other localities, identified as different species, have vertebrae which match diagnostic features for D. hatcheri. So too with the pubis, given that illustrations are all that’s available, it could be easily confused with other species.

They found that characteristics diagnosing D. hatcheri “are shared with other species of Deinosuchus, themselves diagnosed by features not preserved in the holotype of D. hatcheri. Specimens from Texas and the Western Interior localities bear massive, inflated dorsal osteoderms…” They go on to explain that specimens from Alabama & other localities, identified as different species, have vertebrae which match diagnostic features for D. hatcheri. So too with the pubis, given that illustrations are all that’s available, it could be easily confused with other species.

Cossette and Brochu go on to explain, “D. hatcheri was diagnostic when it was named.” They relate that some authors have previously argued that Dienouchus is monotypic (Schwimmer, 2002 & Irmis et al, 2013). Monotypic means represented by a single species. The discovery of more complete material has shown that D. hatcheri could not be distinguished from D. riograndensis or D. rugosus…

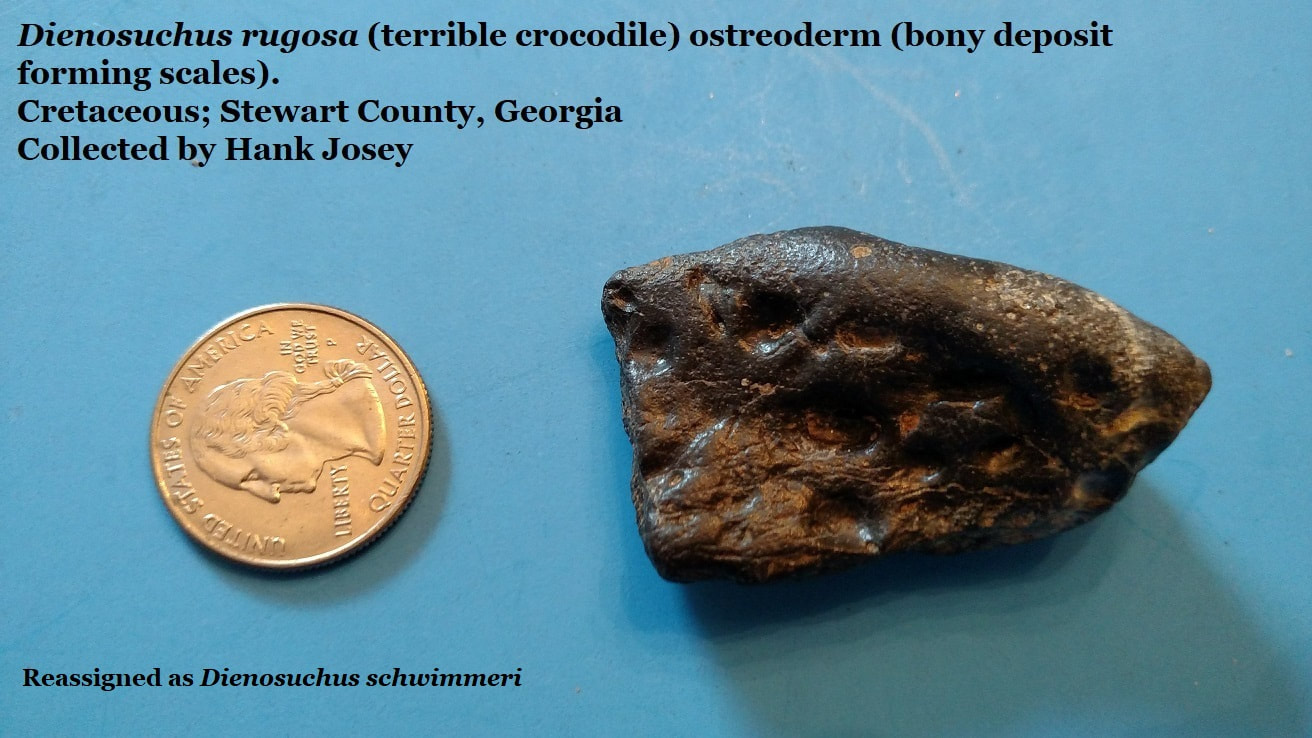

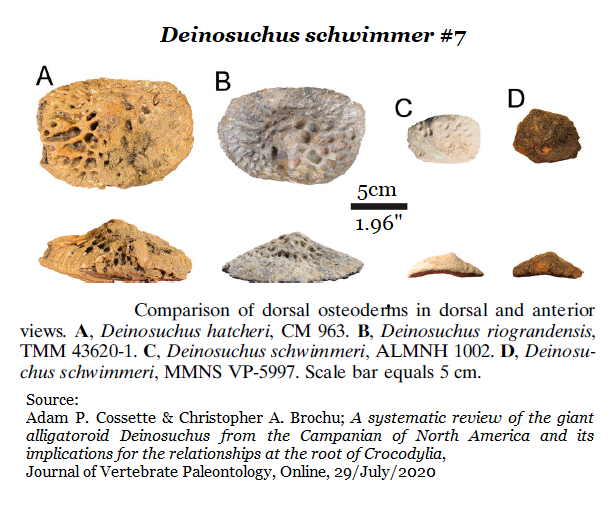

The authors then tentatively revise the diagnostics for Deinosuchus hatcheri, observing that the lateral shield osteoderm has an indentation along one edge, (see image below) and this may prove to be a distinguishing characteristic.

“However,” they quickly add, “D. riograndensis & D. schwimmeri do not preserve osteoderms of the lateral margin of the dorsal shield, and future discoveries may indicate that the state is shared among the species.”

“However,” they quickly add, “D. riograndensis & D. schwimmeri do not preserve osteoderms of the lateral margin of the dorsal shield, and future discoveries may indicate that the state is shared among the species.”

The authors conclude that Deinosuchus hatcheri is possibly undefinable as a species, that the originally reported diagnostic features cannot, with the current fossil record, differentiate D. hatcheri from D. rugosus or D. riograndensis.

Perhaps the osteoderm indentation will prove useful towards retaining D. hatheri as a species, but currently not enough material has been reported, imaged and documented.

All that said, replacing a holotype is not easily done, nor should it be, Deinosuchus hatcheri remains the holotype for Deinosuchus pending petitions to replace it with Deinosuchus riograndensis on the argument that ample material from multiple individuals exist.

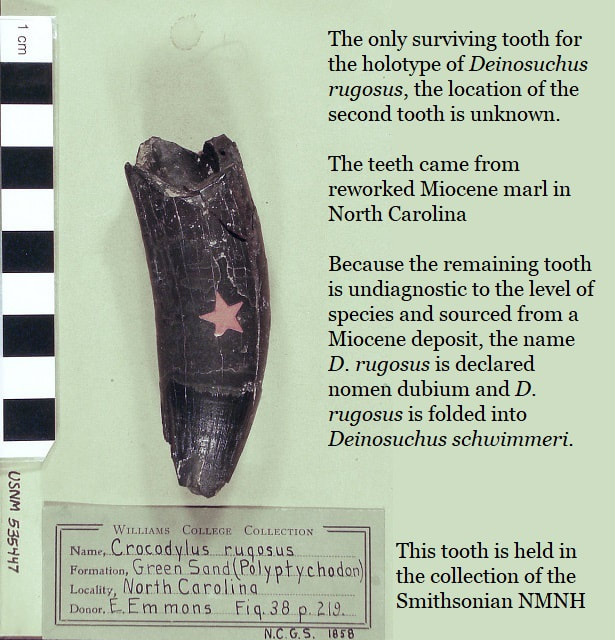

Deinosuchus rugosus

In 1858 E. Emmon assigned two teeth found in a Miocene marl bed near Elizabethtown, Bladen County, North Carolina as belonging to a Cretaceous crocodilian Polyptchodon rugosus. This was reassigned Deinosuchus rugosus. The Miocene sediments have been shown to carry reworked Cretaceous material.

Currently there is just a single tooth held in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (USNM PAL 535447) to form the type specimen for Deinosuchus rugosus.

The fate of the second tooth is unreported in the paper.

In 1858 E. Emmon assigned two teeth found in a Miocene marl bed near Elizabethtown, Bladen County, North Carolina as belonging to a Cretaceous crocodilian Polyptchodon rugosus. This was reassigned Deinosuchus rugosus. The Miocene sediments have been shown to carry reworked Cretaceous material.

Currently there is just a single tooth held in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (USNM PAL 535447) to form the type specimen for Deinosuchus rugosus.

The fate of the second tooth is unreported in the paper.

The name Polyptchodon was commonly used commonly used during the 19th century for Late Cretaceous crocodilian fauna of southern England.

In 1871 Edward Drinker Cope assigned the Polyptchodon tooth as a Thecachampsa, which is a junior synonym for Crocodylus.

In 1902 Professor Oliver Perry Hay reassigned the same North Carolina tooth as Crocodylus rugosus.

In 1979 D. Baird and Jack Horner re-evaluated the North Carolina fossil Emmons had published in 1858 and determined the tooth to be from a species of Deinosuchus.

The name Polyptchodon was commonly used commonly used during the 19th century for Late Cretaceous crocodilian fauna of southern England.

In 1871 Edward Drinker Cope assigned the Polyptchodon tooth as a Thecachampsa, which is a junior synonym for Crocodylus.

In 1902 Professor Oliver Perry Hay reassigned the same North Carolina tooth as Crocodylus rugosus.

In 1979 D. Baird and Jack Horner re-evaluated the North Carolina fossil Emmons had published in 1858 and determined the tooth to be from a species of Deinosuchus.

In 2002 David Schwimmer determined that the original type specimen used to erect the genus Polyptchodon came from a pliosaur, and was not a crocodilian material after all.

As far as the North Carolina tooth, the thick, vertically striated enamel used by Emmons to diagnose the species indicated that the tooth is likely a Deinosuchus and from a mid-jaw location. But the authors report that the single North Carolina tooth cannot, on its own standing, be referenced to the level of species.

Furthermore, “Here, the authors, in agreement with Irmis et al. (2013), assert that the combination of the uncertain stratigraphic placement of the type, undiagnostic morphology, and lack of more complete material from the type locality renders D. rugosus a nomen dubium.”

Thus, Deinosuchus rugosus is overturned as a species.

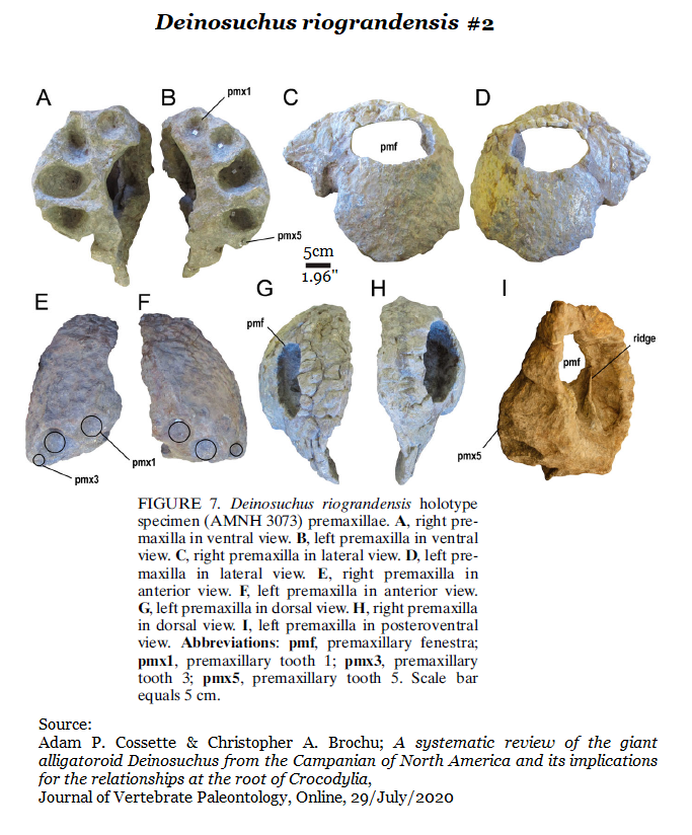

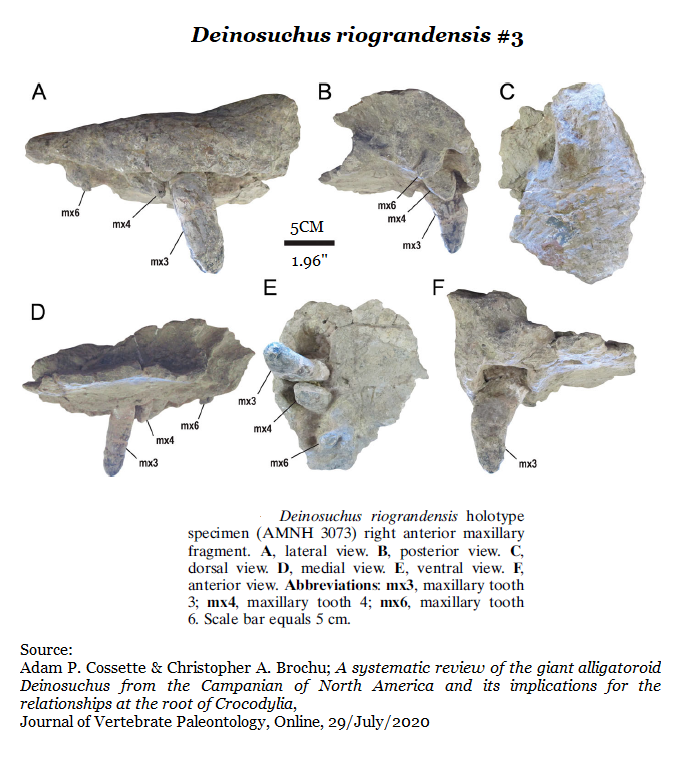

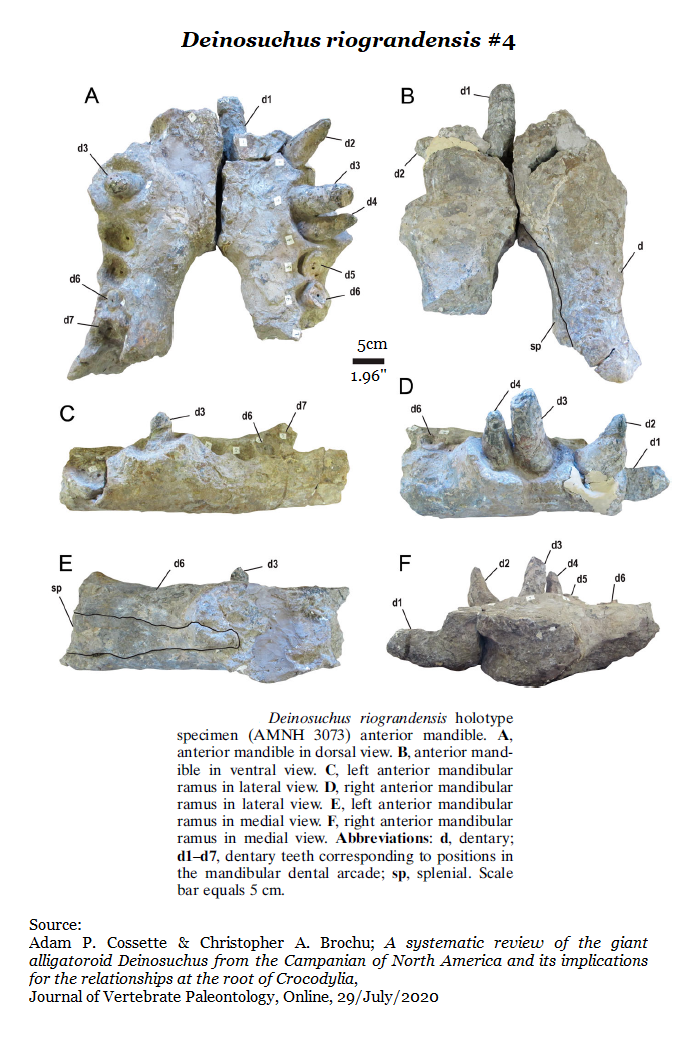

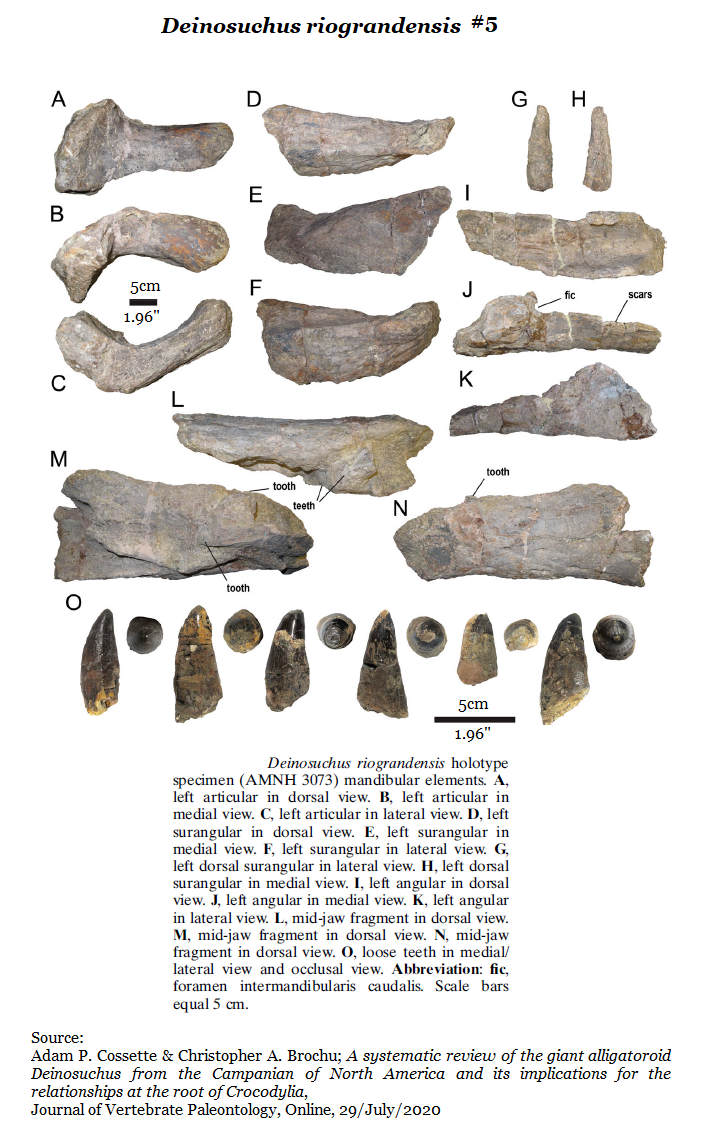

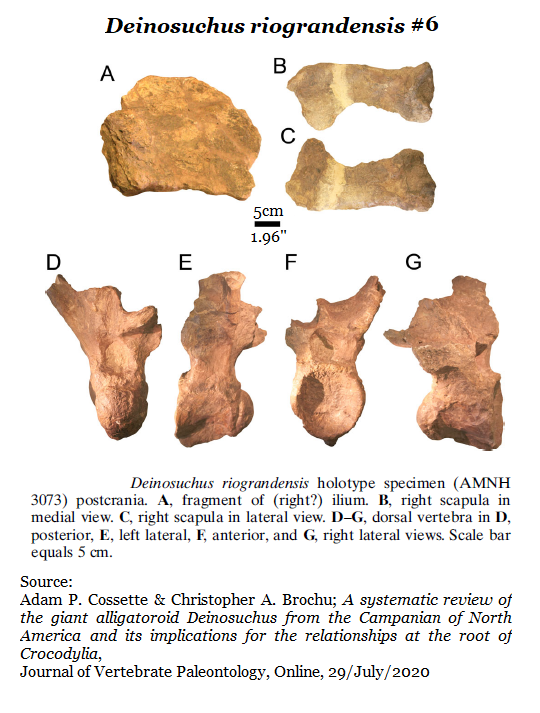

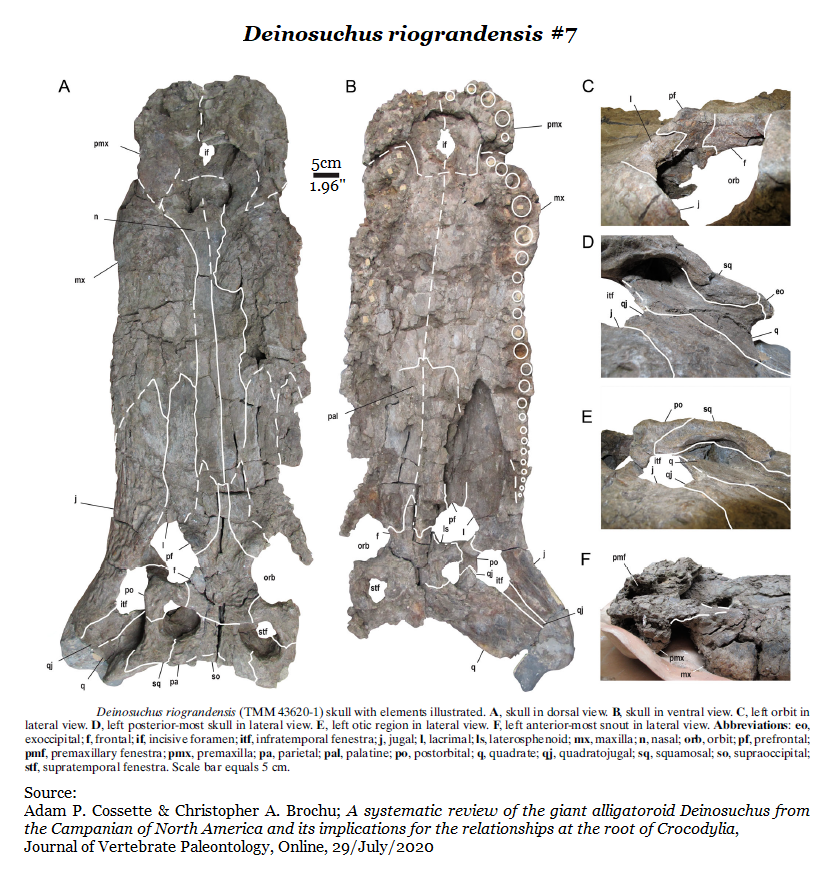

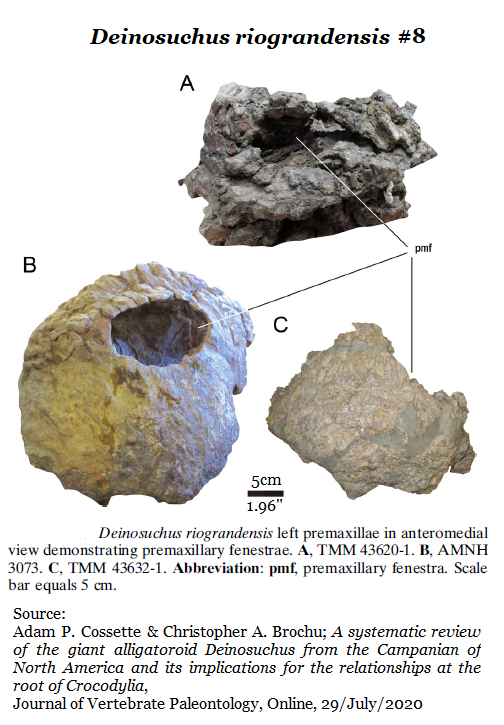

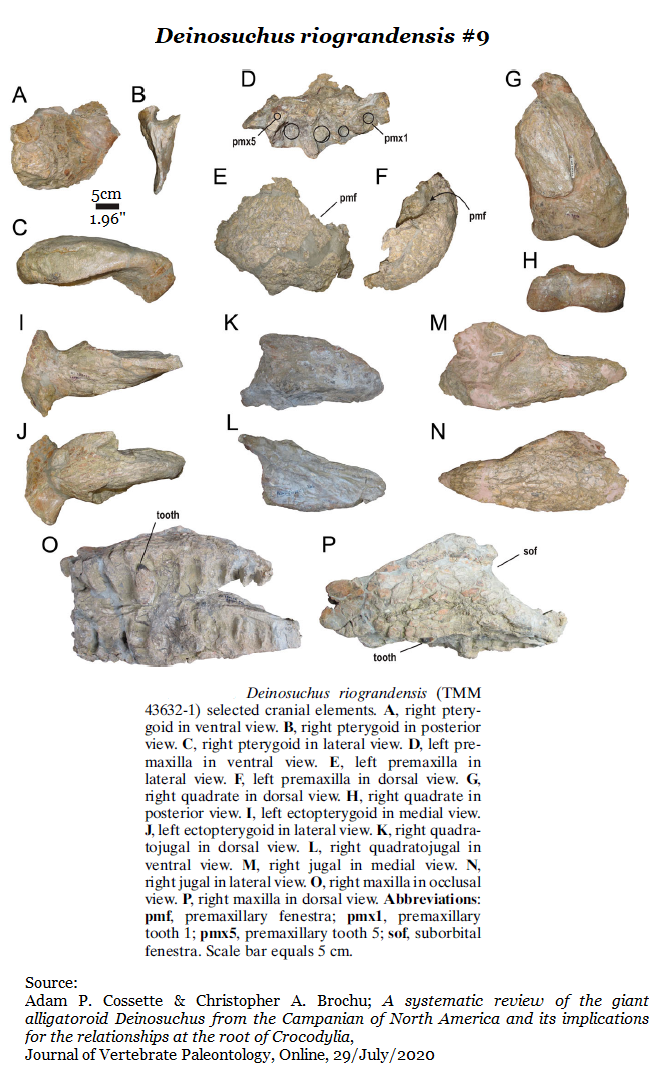

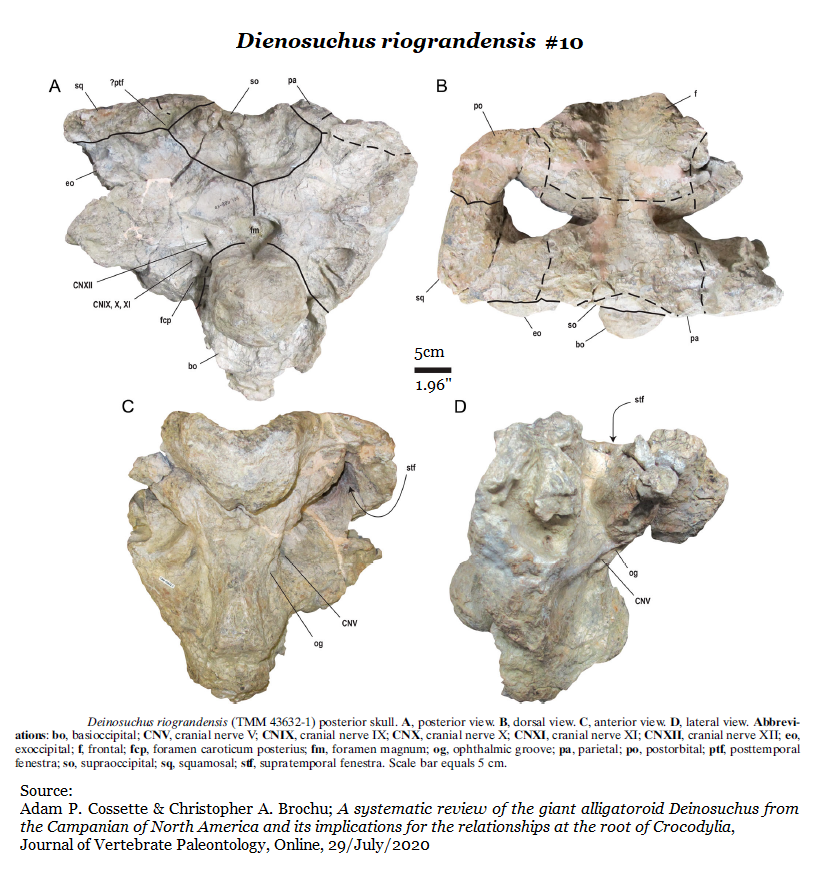

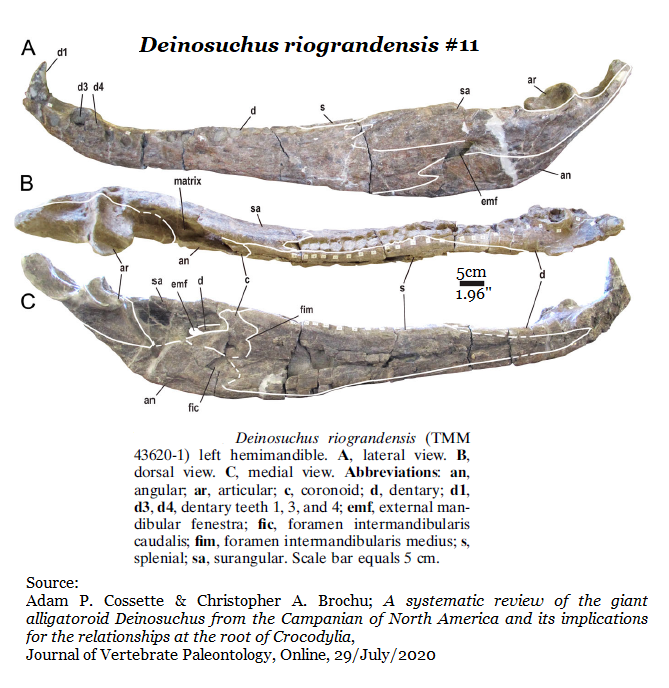

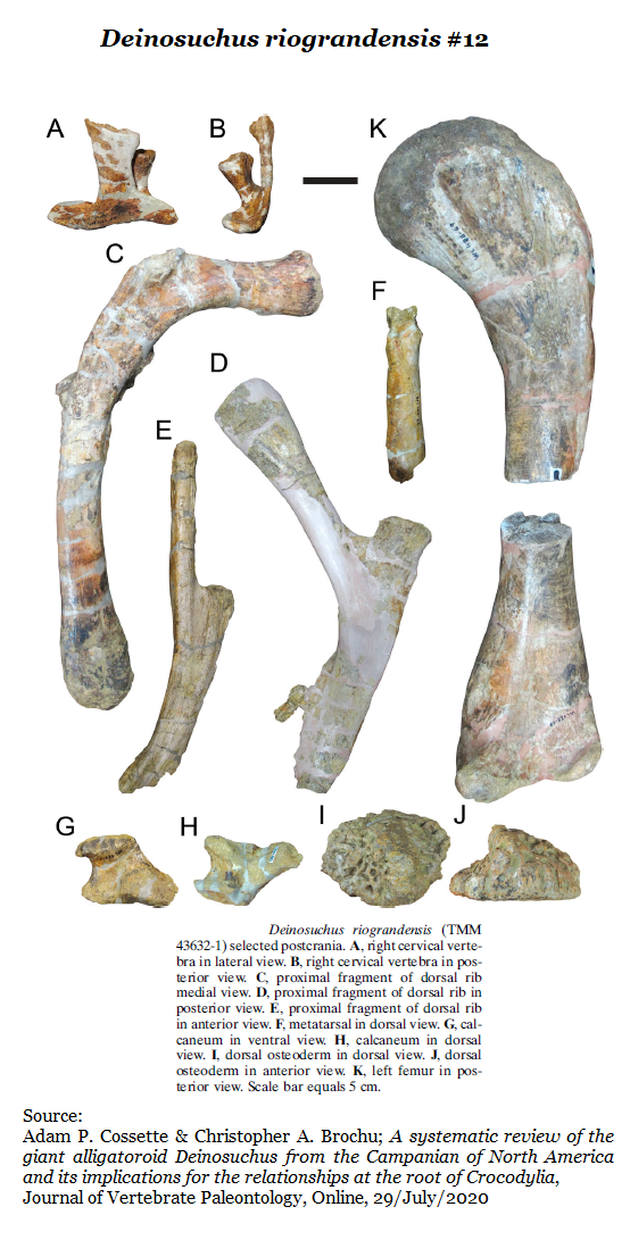

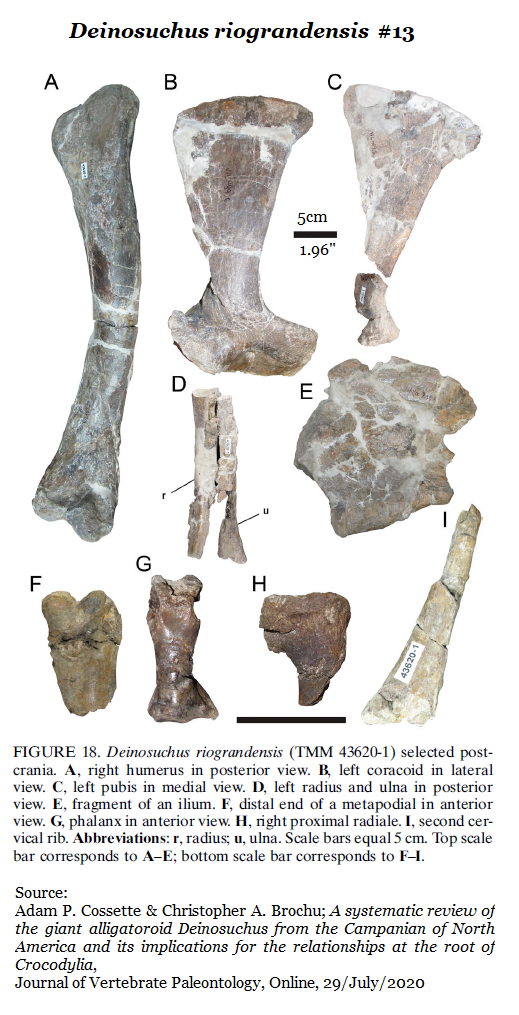

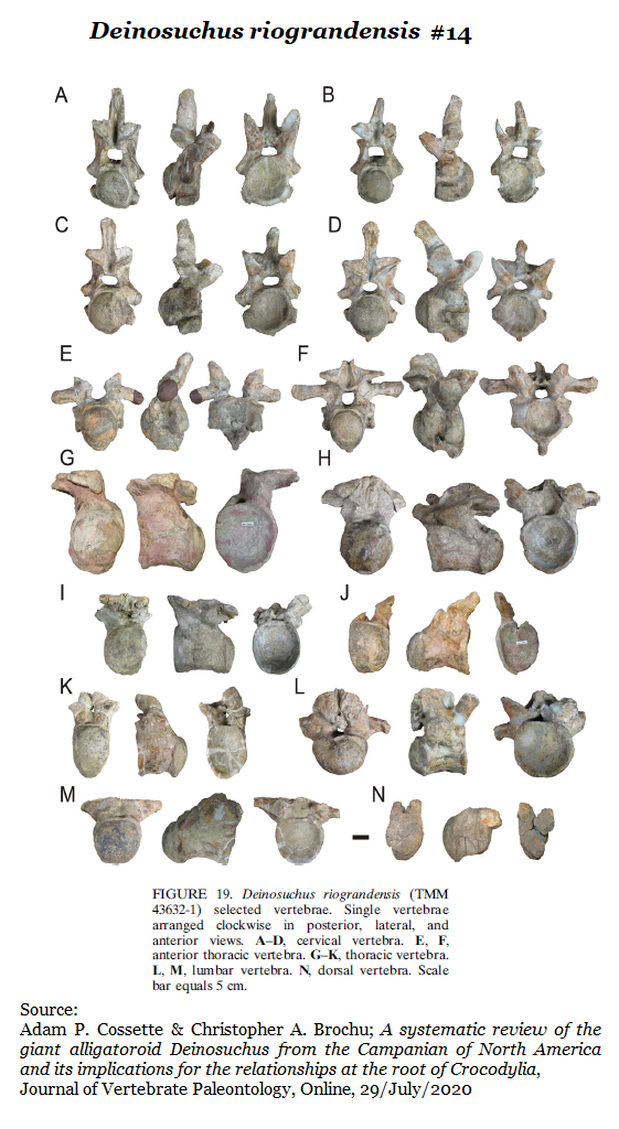

Deinosuchus riograndensis

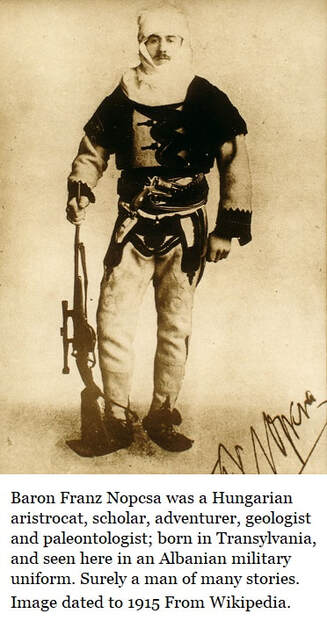

Deinosuchus riograndensis was found in Texas and was established as a species in 1954 by E. H. Colbert and R. T. Bird under the genus name Phobosuchus. A genus which was erected in 1924 by the adventurous Baron Franz Nopsca for closely related croc species in South America.

Colbert and Bird based their Texas specimen on a mostly incomplete skull, mandible, dorsal vertebra, right scapula, superior portion of the right ilium (a hip bone), osteoderms, and other fragments which couldn’t be identified.

The fossil were found in the Aguja Formation of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas. The Aguja Formation is dated to the Campanian Stage of the Cretaceous Period, which spans 72.1 to 83.6 million years ago. The 1954 researchers based their diagnosis on the large size of the specimen, the robust teeth, inflated osteoderms, and upper jawbone arrangement. Only the upper jawbone arrangement is diagnostic to the level of the species, the other fossils only reach to the level of genus.

Deinosuchus riograndensis was found in Texas and was established as a species in 1954 by E. H. Colbert and R. T. Bird under the genus name Phobosuchus. A genus which was erected in 1924 by the adventurous Baron Franz Nopsca for closely related croc species in South America.

Colbert and Bird based their Texas specimen on a mostly incomplete skull, mandible, dorsal vertebra, right scapula, superior portion of the right ilium (a hip bone), osteoderms, and other fragments which couldn’t be identified.

The fossil were found in the Aguja Formation of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas. The Aguja Formation is dated to the Campanian Stage of the Cretaceous Period, which spans 72.1 to 83.6 million years ago. The 1954 researchers based their diagnosis on the large size of the specimen, the robust teeth, inflated osteoderms, and upper jawbone arrangement. Only the upper jawbone arrangement is diagnostic to the level of the species, the other fossils only reach to the level of genus.

Preservation of the holotype, as with all Texas Deinosuchus, is through calcium carbonate salts. Eastern species of Deinosuchus are preserved in calcium phosphate salts a reported by Schwimmer in 2002. The calcium carbonate salt preservation in Texas makes the fossils prone to extensive cracking, as seen in some of the images. This tends to obscure details, morphology, and bone sutures. In many better-preserved specimens free of cracks, sutures are still difficult to discern. The large size of the specimens and lack of sutures may simply indicate maturity.

As seen in these images, there is ample material to distinguish Deinosuchus riograndensis as a separate species. This was a very large, capable predator. To date, its fossils have only been reported from the western shores of the Western Interior Seaway.

As seen in these images, there is ample material to distinguish Deinosuchus riograndensis as a separate species. This was a very large, capable predator. To date, its fossils have only been reported from the western shores of the Western Interior Seaway.

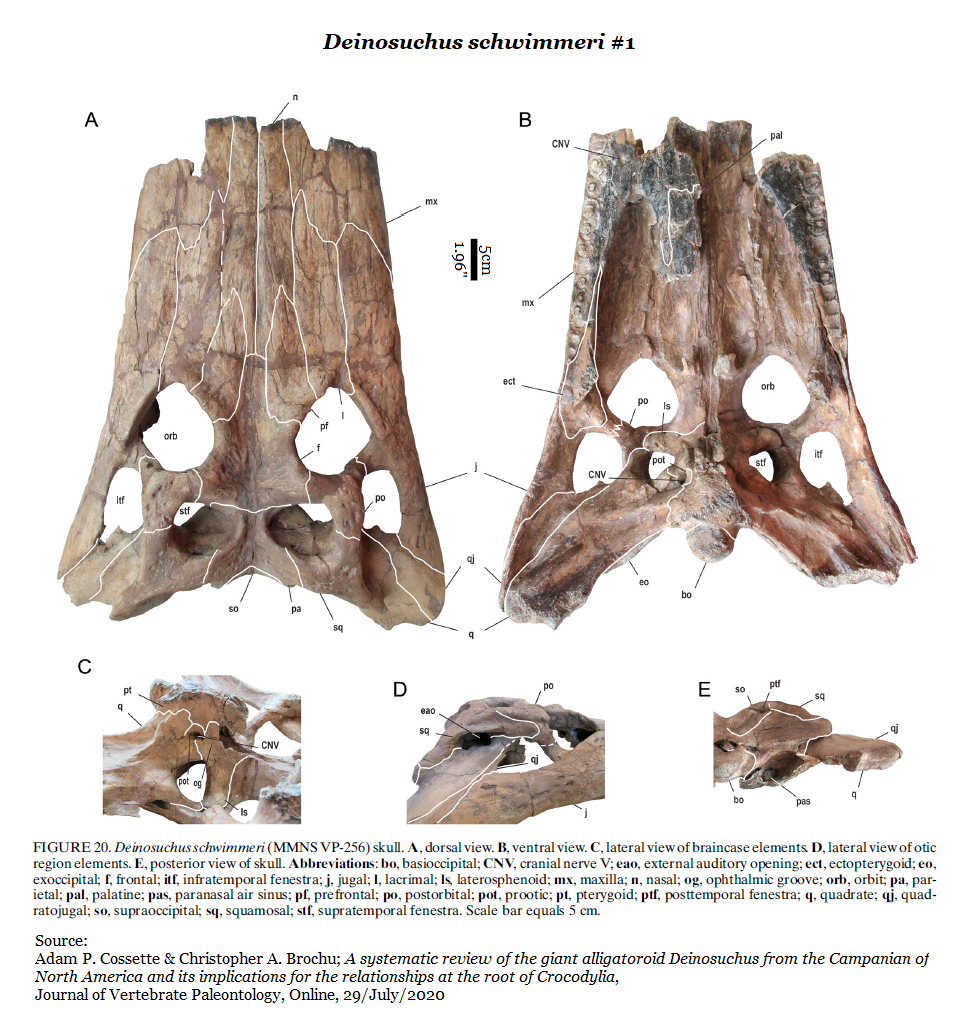

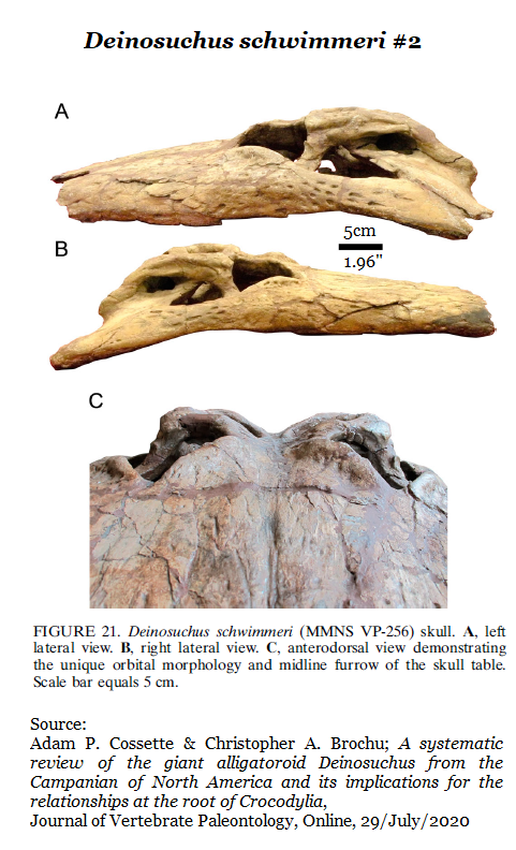

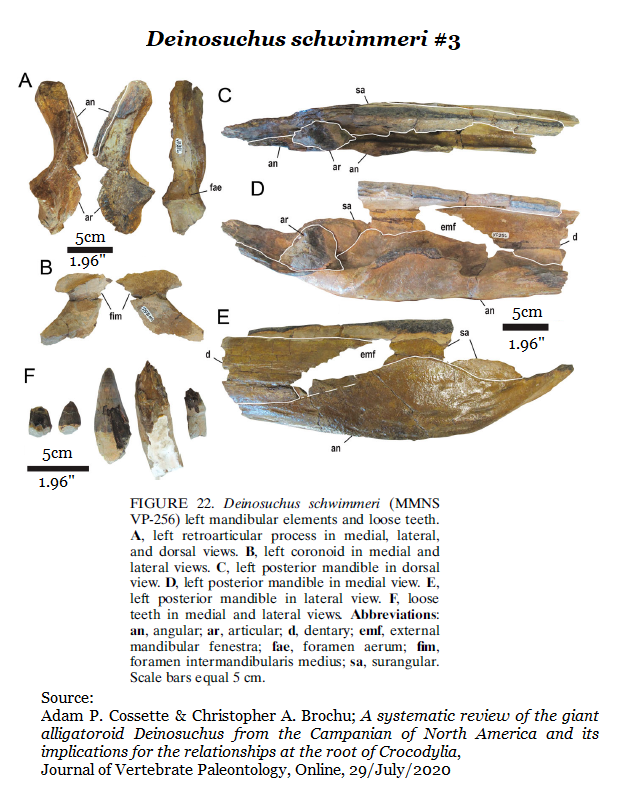

Deinosuchus schwimmeri

The holotype fossil for Deinosuchus schwimmeri is held in Jackson, Mississippi at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Sciences as specimen# MMNS VP-256. This is highly regarded institution which takes the curation and stewardship of fossils very seriously. Dr. George Philips, their Curator of Paleontology is a respected friend who can be found, from time to time, commenting on posts in Facebook’s Georgia’s Fossils Group and who has contribution information to this website.

The holotype fossil for Deinosuchus schwimmeri is held in Jackson, Mississippi at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Sciences as specimen# MMNS VP-256. This is highly regarded institution which takes the curation and stewardship of fossils very seriously. Dr. George Philips, their Curator of Paleontology is a respected friend who can be found, from time to time, commenting on posts in Facebook’s Georgia’s Fossils Group and who has contribution information to this website.

Where D. riograndensis dwelled on the western shores of the Western Interior Seaway. Deinosuchus Schwimmeri hunted our eastern shores, in some numbers. All eastern specimens, including Deinosuchus rugosus and Deinosuchus hatcheri, have been reassigned as Deinosuchus schwimmeri.

D. riograndensis and D. schwimmeri were separated hundreds of kilometers of the marine Western Interior Seaway. Modern alligatoroids cannot tolerate long exposure to salt water, its assumed this also applies to the genus Deinosuchus. If that’s true, then the seaway would have been a barrier, hundreds of miles wide, between the species.

Of course, 600 miles of Pacific Ocean separates South America from the Galapagos Islands. Both tortoises and iguanas managed to accidentally cross that distance often enough to establish multiple species. So Thomas, for one, isn’t willing to bet that individuals of the Deinocuhus genus didn’t accidentally cross the Western Interior Seaway from time to time.

Of course, 600 miles of Pacific Ocean separates South America from the Galapagos Islands. Both tortoises and iguanas managed to accidentally cross that distance often enough to establish multiple species. So Thomas, for one, isn’t willing to bet that individuals of the Deinocuhus genus didn’t accidentally cross the Western Interior Seaway from time to time.

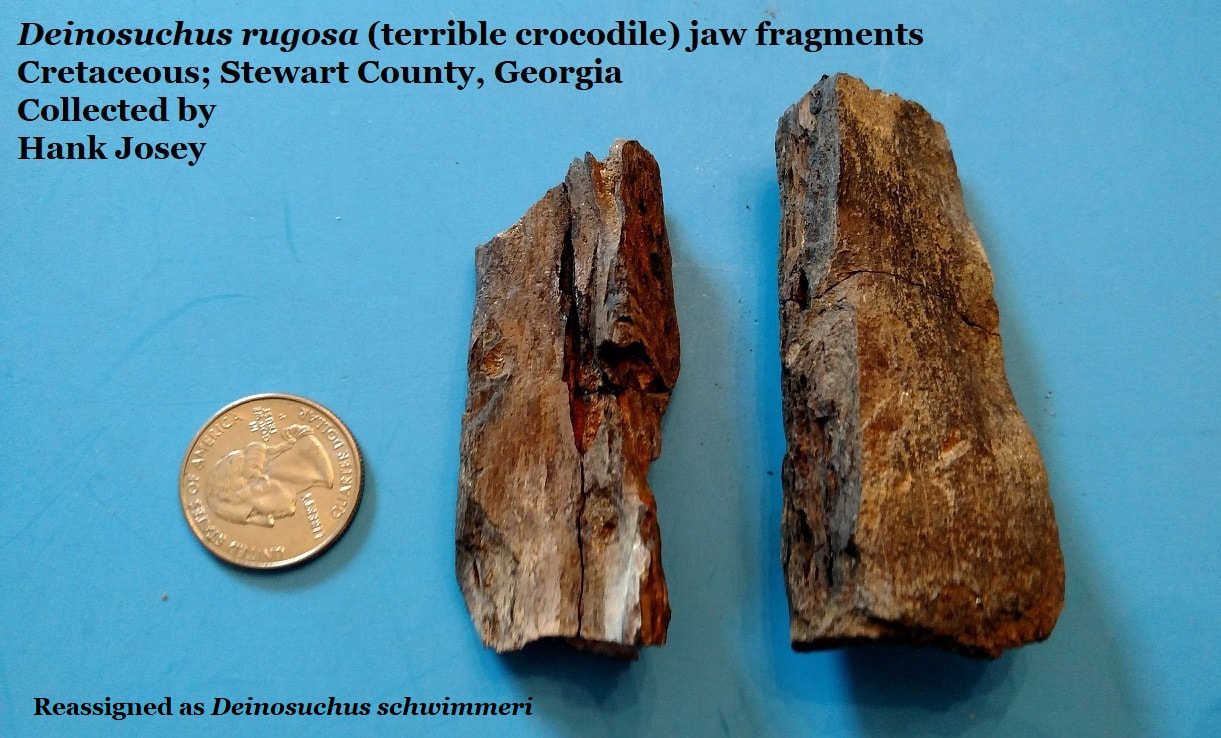

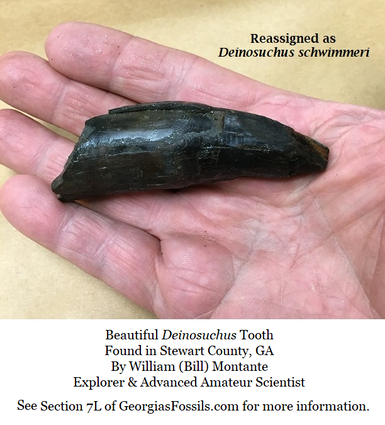

Deinosuchus schwimmeri is a smaller animal than D. riograndensis. However, where the D. riograndensisis relatively rare occurrence in the west, here on the eastern side of that lost sea, Deinosuchus schwimmeri are relatively common fossils though in Georgia articulated remains are rare. Typical finds are teeth, osteoderms and bone fragments. They occur frequently enough to suggest a rather large population.

And while "smaller" is true, and this is clear from the fossils, please don't form the misconception that D. Schwimmeri was less than a monstrous, giant croc. A 29 foot predator weighing more than 2 tons is terrifying.

Thankfully our species was still 80+ million years in the future so we never had to face such a terrifying beast as a croc capable of taking down dinosaurs. But the below illustration give you an idea of what it would be like to face such a beast. We'd be little more than a snack.

The Georgia come from the Blufftown Formation which is dated to 82 million years old and represents the oldest known Deinosuchus specimens.

The authors describe the Mississippi Museum specimen VP-256, as a beautifully preserved partial posterior skull and partial mandible. It was discovered in the Coffee Sand Formation of Lee County, Mississippi.

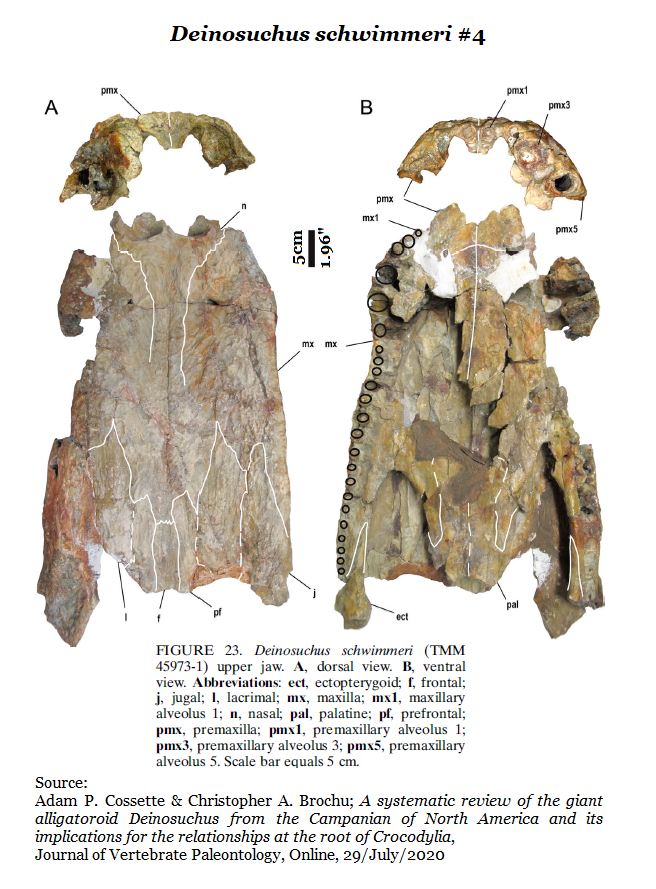

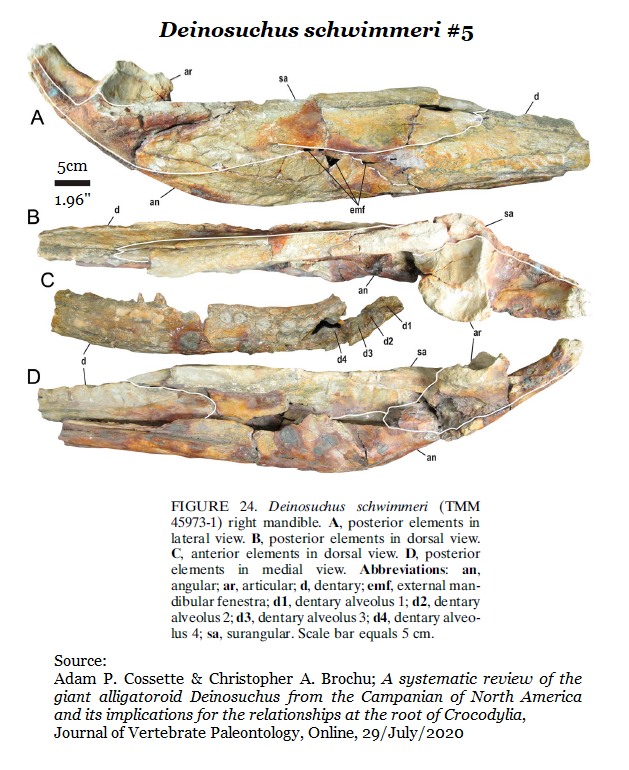

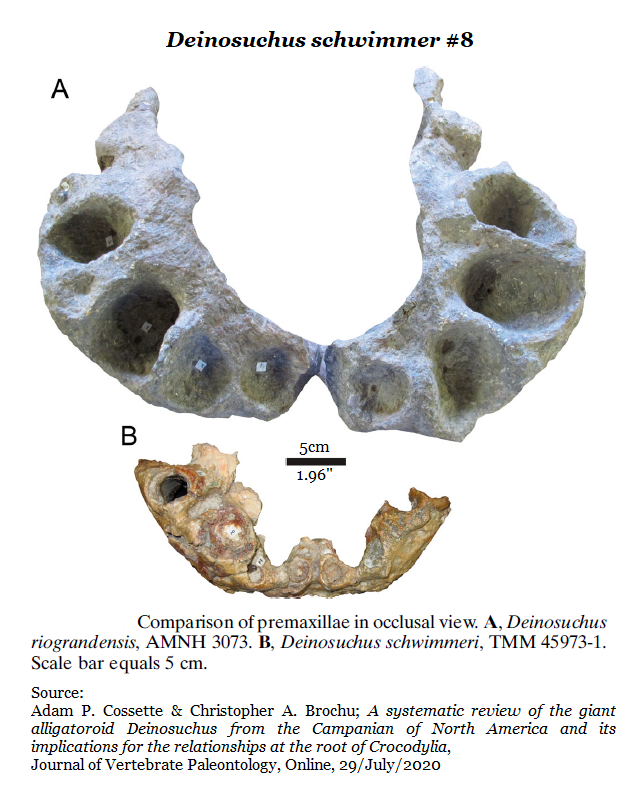

Additional reference material is held in the Texas Memorial Museum of Austin and is cataloged as specimen# TMM 45973-1. This consist of an excellent upper jaw and mandible. Further reference specimens establishing the species, vertebrae, osteoderms & various bones are held in the Alabama Museum of Natural History as specimen# ALMNH 1002.

All imaged specimens are seen below.

The authors describe the Mississippi Museum specimen VP-256, as a beautifully preserved partial posterior skull and partial mandible. It was discovered in the Coffee Sand Formation of Lee County, Mississippi.

Additional reference material is held in the Texas Memorial Museum of Austin and is cataloged as specimen# TMM 45973-1. This consist of an excellent upper jaw and mandible. Further reference specimens establishing the species, vertebrae, osteoderms & various bones are held in the Alabama Museum of Natural History as specimen# ALMNH 1002.

All imaged specimens are seen below.

The authors speculate over the difference in size between D. riograndensis and D. schwimmeri stating that the western, D. riograndensis species is typically much larger.

They question whether the difference in size is environmental rather than hereditary. If there was a greater abundance of prey and generally better habitat. They additionally speculate that longevity might also have played a role in size as the croc family tends to keep growing throughout their life and eastern species may have faced more environmental hazards.

Cossette and Brochu also explore the possibility that body temperature regulation, simple cooling, may have played a role in size. Both species have largish nasal passages which would have helped prevent overheating. But as such large animals are also assumed to have very powerful bite forces, you would assume large nasal passages would weaken the snout. Evolution is a subtle thing.

Larger size typically means a more stable body temperature, but larger animals are more easily overheated and harder to cool.

Today, the Southeastern climate is far more humid than the climate of Texas, making it much more difficult to regulate body temperatures here in Georgia. But this may not have been the case 80 million years ago.

Difficult questions to answer with the current state of knowledge. Extensive populations of both species existed. More field and lab work could give us a better understanding of contemporary environments and available prey populations.

They question whether the difference in size is environmental rather than hereditary. If there was a greater abundance of prey and generally better habitat. They additionally speculate that longevity might also have played a role in size as the croc family tends to keep growing throughout their life and eastern species may have faced more environmental hazards.

Cossette and Brochu also explore the possibility that body temperature regulation, simple cooling, may have played a role in size. Both species have largish nasal passages which would have helped prevent overheating. But as such large animals are also assumed to have very powerful bite forces, you would assume large nasal passages would weaken the snout. Evolution is a subtle thing.

Larger size typically means a more stable body temperature, but larger animals are more easily overheated and harder to cool.

Today, the Southeastern climate is far more humid than the climate of Texas, making it much more difficult to regulate body temperatures here in Georgia. But this may not have been the case 80 million years ago.

Difficult questions to answer with the current state of knowledge. Extensive populations of both species existed. More field and lab work could give us a better understanding of contemporary environments and available prey populations.

Reference

Adam P. Cossette & Christopher A. Brochu (2020) A systematic review of the giant alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Campanian of North America and its implications for the relationships at the root of Crocodylia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 40:1, e1767638, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1767638

Adam P. Cossette & Christopher A. Brochu (2020) A systematic review of the giant alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Campanian of North America and its implications for the relationships at the root of Crocodylia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 40:1, e1767638, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1767638