13: Ziggy and the Museum of Arts and Sciences,

Macon, GA.

Dorudon, Zygorhiza,

& the fantasy monster Hydrarchos.

By

Thomas Thurman

The fertile seas of Georgia have known whales for as long as fully marine whales have existed. Before the modern toothed and baleen whales there were the diverse basilosaurids and they too hunted the sea which covered South Georgia 34 million years ago, and more.

Ziggy, the fossilized whale on permanent display at the Museum of Arts & Sciences in Macon is one of the more famous whales which hunted Georgia’s sea 33.5 million years ago. Ziggy is as articulated Dorudon serratus. It has an interesting history including thirty-plus years mistakenly displayed as Zygorhiza kochii. This error was only recently revealed by Dr. Mark Uhen, an expert in whale evolution from George Mason University and the display is in the process of being corrected. The reclassification rests on the lower molars and robust elements of the skeleton.

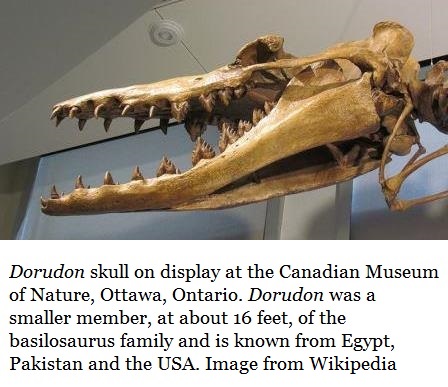

Two of the genera in the large basilosaurid family are Dorudon and Zygorhiza, closely related whales who even shared a sea though they to preferred different environments within that Southeastern sea.

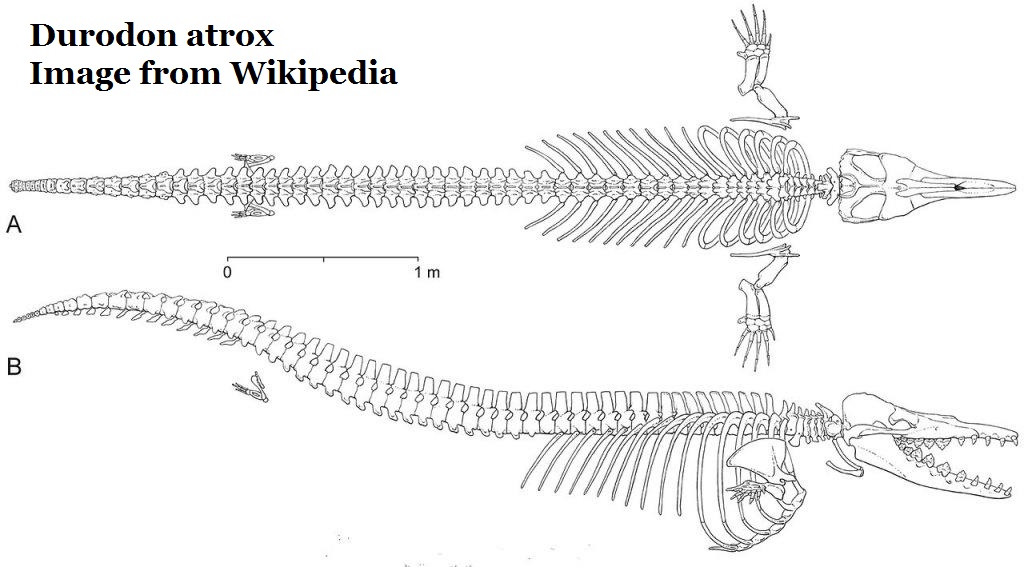

Both tended towards 5 meters or 16 feet in length with big skulls a meter long. They were among the first fluked whales and capable swimmers.

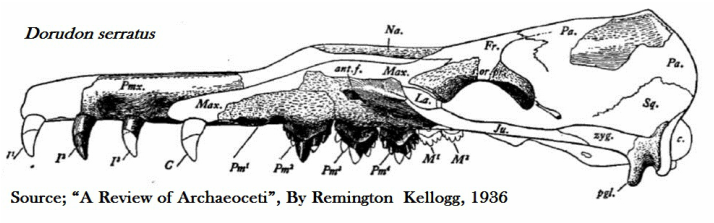

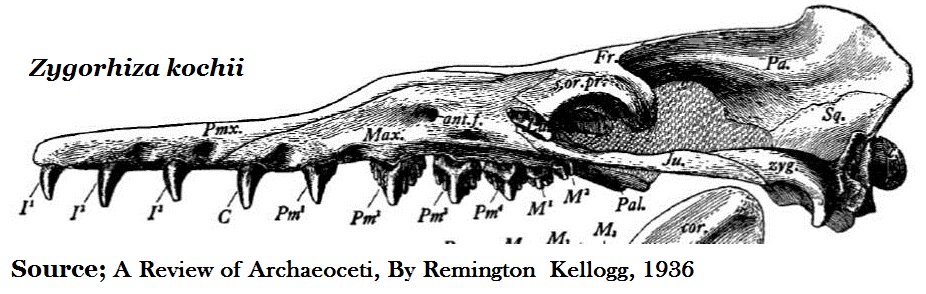

Like all of the basilosaurids, both Dorudon and Zygohiza were well equipped for hunting the fertile Eocene seas. They possessed forward spike-like teeth for seizing prey, large rear triangular teeth for shearing prey into manageable portions; powerful teeth and jaws, capable of shearing through shell at need. This basic tooth arrangement served many species of early whales for more than 10 million years.

Of the two, Zygorhiza is more delicate, more gracile in its bone structure and Dorudon is sturdier, more robust and massive in its structure. Dorudon is also more widespread globally in both time and geographic range.

Dorudon

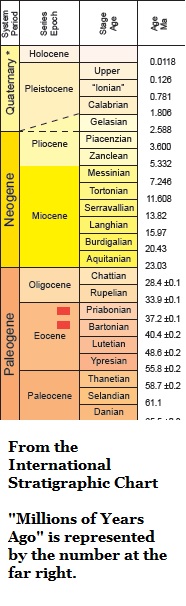

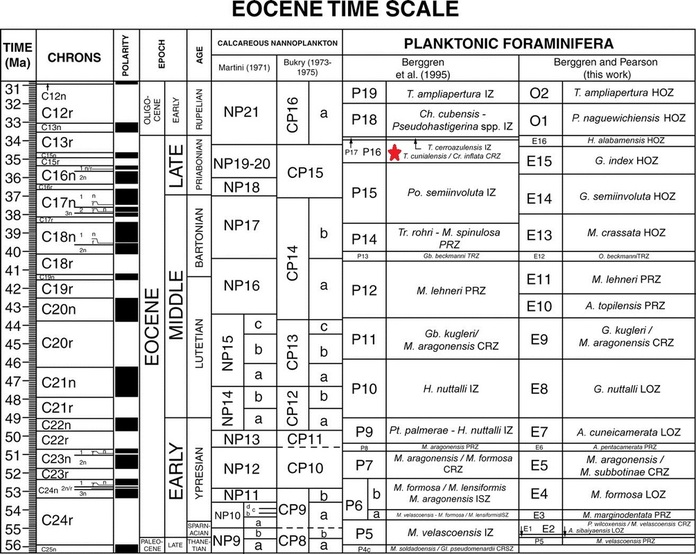

The genus Dorudon occurs in the Bartonian and Priabonian sediments of North America and the Priabonian of North and West Africa. (See geologic time chart below) Dorudon is a medium sized member of the basilosaurid family. It is well known from the Southeastern USA.

Dorudon serratus was erected as a species in 1845 by Robert Wilson Gibbs through teeth originating from South Carolina. It is fully realized basilosaurid with highly ornamented (serrated) molars, atrophied hind limbs and the end-of-tail vertebrae arrangement of a whale which possessed flukes.

The genus Dorudon is the likely ancestor to all modern whales; it is also, very probably a descendent of our own Georgiacetus vogtlensis (section 10).

The genus Dorudon occurs in the Bartonian and Priabonian sediments of North America and the Priabonian of North and West Africa. (See geologic time chart below) Dorudon is a medium sized member of the basilosaurid family. It is well known from the Southeastern USA.

Dorudon serratus was erected as a species in 1845 by Robert Wilson Gibbs through teeth originating from South Carolina. It is fully realized basilosaurid with highly ornamented (serrated) molars, atrophied hind limbs and the end-of-tail vertebrae arrangement of a whale which possessed flukes.

The genus Dorudon is the likely ancestor to all modern whales; it is also, very probably a descendent of our own Georgiacetus vogtlensis (section 10).

Zygorhiza

Zygorhiza is known from Priabonian sediments. It’s unconfirmed in Georgia and the southeastern United States; seemingly only occurring west of paleo-Mississippi River in murkier sediments. It is also reported from New Zealand.

The genus is listed on this site due to several misidentified specimens reported from Georgia; these have generally been re-assigned as Dorudon.

Named for a Charlatan

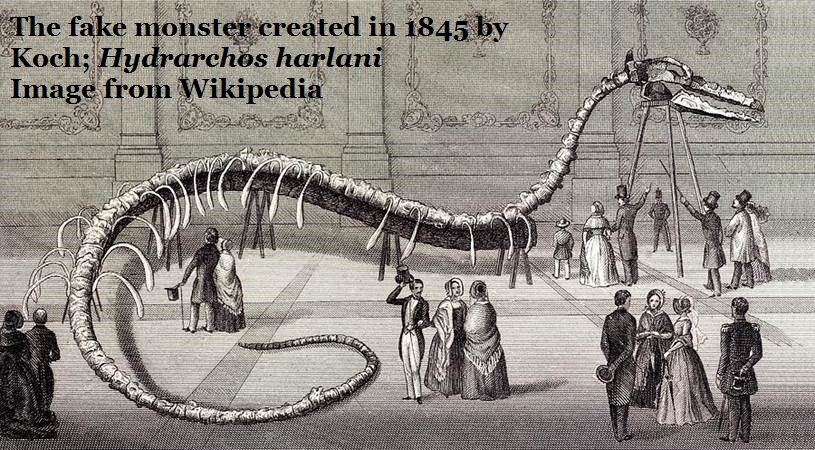

The fascinating history of Zygorhiza Kochii begins in 1845 when Albert Koch went to Alabama and collected enough material from several localities to assemble a 114 foot skeleton meant as a scientific deception and a traveling public display.

Koch had experience along these lines; this was not his first charade. In 1840 he’d assembled the Missourium; a (super)mastodon reconstruction elongated with additional vertebrae and tusks set in the most frightening position possible.

Next Koch turned to sea monsters. Despite marketing claims, Koch’s latest creation was no scientific specimen as the priority in construction was on a dramatic display which would attract crowds. Originally he named his beast Hydrargos silllimani, but later changed the name to Hydrarchos harlani at Dr. Benjamin Silliman’s request.

Even the skull was assembled from multiple species collected at multiple locations; contemporary scientists noticed this immediately.

After touring Europe, Koch sold Hydrarchos to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV who exhibited it in Berlin’s Royal Anatomical Museum despite protest by the museum’s experts.

Koch then returned to Alabama, assembled a second 96ft Hydrarchos which he took on tour. This second one was later sold to a Chicago curiosities museum and finally destroyed in the Great Chicago fire of 1871.

The original Hydrarchos was destroyed in World War II by allied bombs.

Zygorhiza is known from Priabonian sediments. It’s unconfirmed in Georgia and the southeastern United States; seemingly only occurring west of paleo-Mississippi River in murkier sediments. It is also reported from New Zealand.

The genus is listed on this site due to several misidentified specimens reported from Georgia; these have generally been re-assigned as Dorudon.

Named for a Charlatan

The fascinating history of Zygorhiza Kochii begins in 1845 when Albert Koch went to Alabama and collected enough material from several localities to assemble a 114 foot skeleton meant as a scientific deception and a traveling public display.

Koch had experience along these lines; this was not his first charade. In 1840 he’d assembled the Missourium; a (super)mastodon reconstruction elongated with additional vertebrae and tusks set in the most frightening position possible.

Next Koch turned to sea monsters. Despite marketing claims, Koch’s latest creation was no scientific specimen as the priority in construction was on a dramatic display which would attract crowds. Originally he named his beast Hydrargos silllimani, but later changed the name to Hydrarchos harlani at Dr. Benjamin Silliman’s request.

Even the skull was assembled from multiple species collected at multiple locations; contemporary scientists noticed this immediately.

After touring Europe, Koch sold Hydrarchos to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV who exhibited it in Berlin’s Royal Anatomical Museum despite protest by the museum’s experts.

Koch then returned to Alabama, assembled a second 96ft Hydrarchos which he took on tour. This second one was later sold to a Chicago curiosities museum and finally destroyed in the Great Chicago fire of 1871.

The original Hydrarchos was destroyed in World War II by allied bombs.

The Scientific Value of Hydrarchos

Many of the fossils used in assembling Hydrarchos had never been seen by science. So despite Koch’s fraud Hydrarchos helped establish the species Zygorhiza kochii.

Frederic W. True established the genus Zygorhiza in 1908 from a rear portion of the skull used by Koch, it included no teeth. The species kochii was founded by Remington Kellogg in 1936 after several years of research and many proposed names by multiple researchers.

To the author’s knowledge; Zygorhiza kochii is the only species named after a known scientific charlatan.

Many of the fossils used in assembling Hydrarchos had never been seen by science. So despite Koch’s fraud Hydrarchos helped establish the species Zygorhiza kochii.

Frederic W. True established the genus Zygorhiza in 1908 from a rear portion of the skull used by Koch, it included no teeth. The species kochii was founded by Remington Kellogg in 1936 after several years of research and many proposed names by multiple researchers.

To the author’s knowledge; Zygorhiza kochii is the only species named after a known scientific charlatan.

Ziggy & the Museum of Arts & Sciences; Macon, Georgia

Ziggy is a wonderful, complete, fully articulated Durodon specimen who has long been identified as a Zygorhiza kochii on public display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA.

Looking at the fossil today, bear in mind that it is a reconstruction where the missing pieces of the original find were “filled in” unintentionally with material from another genus and species.

Generally speaking the lighter material is the original fossils, the darker material was added to complete the specimen; a process which created its own set of problems, as we’ll see.

Ziggy represents a fascinating history wrapped in mining, amateur research, education support, professional review, and display construction. A history which shows how paleontology progresses, mistakes happen, and the effort towards correcting the mistakes begins.

Location, Location, Location

The fossil was discovered in J.M. Huber Corporation’s Kaolin Mine #34 in June, 1973 by amateur mineralogist and paleontologist Bill Christy and his son, Billy.

Bill Christy is very well known in Georgia’s geology and paleontology; he was famous for creating fully identified egg-carton collections of minerals and fossils which he freely gave away to schools, teachers, and interested parties.

The Huber Corporation became Kamin Performance Minerals a few years ago. Carl Joyce, Senior Exploration Geologists for Kamin Performance Minerals, recently put me in touch with Phil Manning who was aware of Ziggy’s history of discovery.

Phil Manning went to work for Huber in 1978 and became Mine Operations Manager for Huber in 1994. He was an undergraduate at the University Of Georgia (UGA) during the 1970s and had geology classes with Billy Christy Jr.

Working at Huber Phil soon met Bill Christy Sr. and then began advising Bill Christy on collecting locations in the various mines.

To quote Phil Manning; “By that time the whale excavation at #34 Mine was history, but it was recent history. I managed to collect and reassemble the details I shared with you about it from various personnel at Huber familiar with the find and dig, and from Dr. Mike Voorhies.”

I spent a day in the field with Phil Manning & Ashley Quinn (Georgia College Natural History Museum) and we visited this site of Mine #34 (Latitude;32°43'49.94"N by Longitude;83°29'34.26"W), but it’s currently leased by a hunting club and hunted year-round. I appreciate Phil showing us around.

Phil reports that, way back when, the decision was made not to reclaim the Mine #34 but leave open and available for collection, education, and research purposes. Unfortunately, this was decades ago and the mining lease has long since expired. Perhaps at some point this small mine will again be available for education and research.

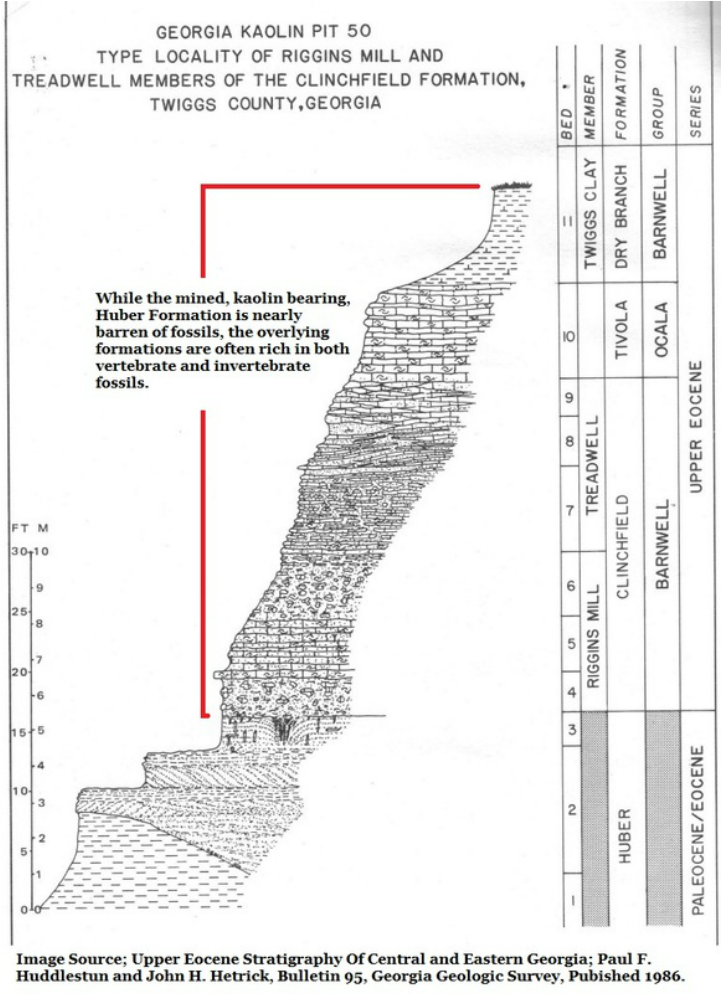

On the discovery of Ziggy, Billy Christy Jr. reports that he and his father had found a vein of calcite crystals in the upper Tivola Limestone and were following it when they encountered a mass of bones, about ten feet above the base of the Twiggs Clay.

Bill Christy called in Dr. Michael Voorhies, with the UGA at the time, to identify the fossil in the field and lead the effort to excavate and study the specimen at the University of Georgia. Dr. Voorhies identified the species as Zygorhiza kochii, which would have been readily accepted at the time but would later prove incorrect.

Dr. Voorhies is famous in his own right; after leaving UGA he stood as Professor of Vertebrate Paleontology at the University of Nebraska. He found national fame as the discoverer of Nebraska Ash Fall Beds which was developed into a state park and yielded many rich and important fossils finds. (http://ashfall.unl.edu/) He has since retired.

Bill Christy Sr. passed away in October 2010 but is fondly remembered by the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society. His son Billy Jr. currently lives in Midland, Texas and maintains membership in the society; he patiently answered many of my questions in a 10, March, 2014 phone interview.

Depending on 41 year old memories; Billy Jr. reported that about 6 inches of Ziggy’s lower snout and both mandibles were present in the sediments along with several ribs, vertebrae, teeth, and other bones.

The excavation began in the fall of 1973 and was complete by January 1974. The specimen jacketed for protection then transported to the University of Georgia for research. About 60% of a non-articulated individual was present. Non-articulated and missing remains suggest post-mortem scavenging of the whale.

Billy Christy Jr. was preparing for college at the time of the discovery and recovery of Ziggy and actively participated in both. He reported that while cleaning the Twiggs Clay from the fossils in the UGA lab he discovered two and a half small sand shark’s vertebrae stuck to the ribs, and some shark teeth. We don't know species of sand shark; there are several known to occur in the Twiggs Clay. This material has since been lost.

The presence of small shark vertebrae stuck to the Ziggy's ribs could certainly be interpreted as a final meal.

With the help of Rick Otto, Superintendent of Nebraska’s Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park I reached Dr. Voorhies for a phone interview on 18, March, 2014.

Dr. Voorhies stated that to his knowledge the specimen had never been seriously studied by science. The belief that it was a Zygorhiza kochii, based on A Review of Archaeocti by Remington Kellogg, did not warrant a research paper as the species was well known from Georgia’s fossil record.

Dr. Voorhies reported that Bill Christy Sr. had always intended for the specimen to end up on display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon where Bill often volunteered and later worked. On March 3rd, 1979 the University of Georgia officially donated Ziggy to the Museum. In a 31, March, 2014 letter Susan Welsh, the Director of the Museum of Arts and Sciences reported that as a condition of the donation Ziggy was to be assembled into a mounted specimen.

From University of Georgia Ziggy travelled to the University of Florida as a disassembled puzzle with pieces missing. There; Robert Allen spent more than two years assembling the current mounting. This was an expensive, time consuming project.

A Zygorhiza kochii from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History was loaned and Ziggy’s missing elements were either cast or modelled from the Smithsonian specimen. This includes most of the skull. Allen mounted the actual Twiggs County fossils; the only artificial material in the current Ziggy display is the Smithsonian material.

This created a problem; Ziggy is actually a mixture of two genera of early whales. The pale original fossils are Dorudon serratus. The darker material is recreated from the Smithsonian Zygorhiza kochii specimen.

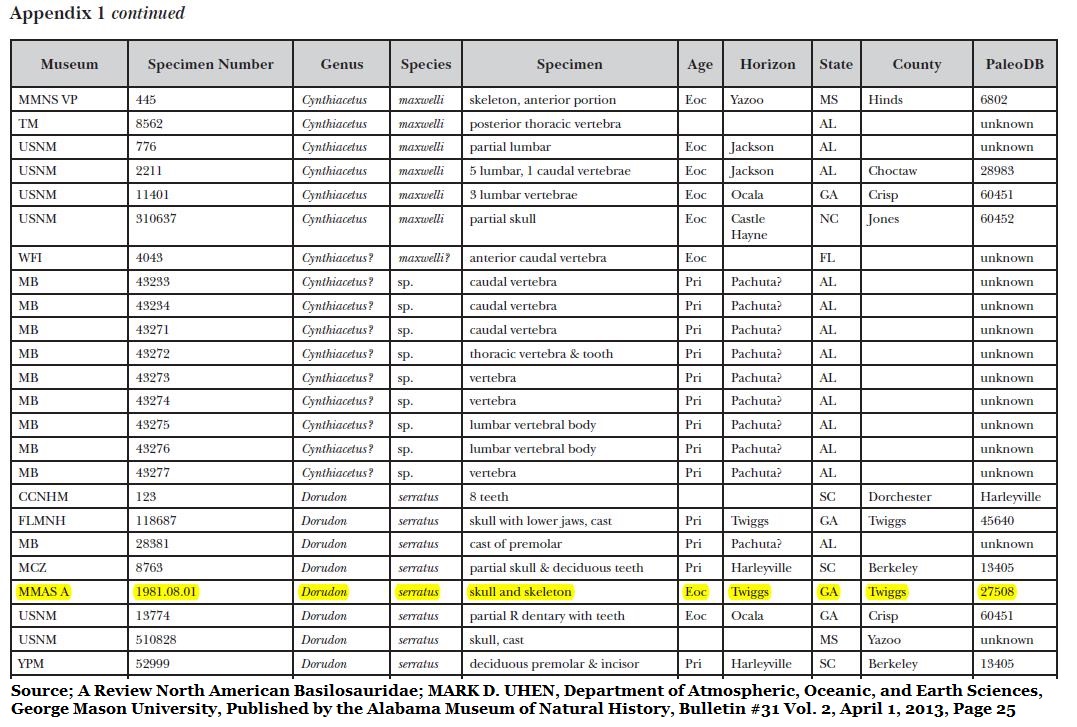

As we’ve seen Dr. Uhen travelled the southeast in 2012 and 2013 reviewing published fossils from various collections while he was working on his paper for the Alabama Museum of Natural History http://almnh.ua.edu/. He stopped in at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon. He didn’t see what he expected to see. As seen below his 2013 paper over basilosaurids classified Ziggy as a Dorudon serratus.

Dr. Voorhies agreed with the reclassification in light of Dr. Uhen’s expertise in basilosaurid whales.

Ziggy is a wonderful, complete, fully articulated Durodon specimen who has long been identified as a Zygorhiza kochii on public display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA.

Looking at the fossil today, bear in mind that it is a reconstruction where the missing pieces of the original find were “filled in” unintentionally with material from another genus and species.

Generally speaking the lighter material is the original fossils, the darker material was added to complete the specimen; a process which created its own set of problems, as we’ll see.

Ziggy represents a fascinating history wrapped in mining, amateur research, education support, professional review, and display construction. A history which shows how paleontology progresses, mistakes happen, and the effort towards correcting the mistakes begins.

Location, Location, Location

The fossil was discovered in J.M. Huber Corporation’s Kaolin Mine #34 in June, 1973 by amateur mineralogist and paleontologist Bill Christy and his son, Billy.

Bill Christy is very well known in Georgia’s geology and paleontology; he was famous for creating fully identified egg-carton collections of minerals and fossils which he freely gave away to schools, teachers, and interested parties.

The Huber Corporation became Kamin Performance Minerals a few years ago. Carl Joyce, Senior Exploration Geologists for Kamin Performance Minerals, recently put me in touch with Phil Manning who was aware of Ziggy’s history of discovery.

Phil Manning went to work for Huber in 1978 and became Mine Operations Manager for Huber in 1994. He was an undergraduate at the University Of Georgia (UGA) during the 1970s and had geology classes with Billy Christy Jr.

Working at Huber Phil soon met Bill Christy Sr. and then began advising Bill Christy on collecting locations in the various mines.

To quote Phil Manning; “By that time the whale excavation at #34 Mine was history, but it was recent history. I managed to collect and reassemble the details I shared with you about it from various personnel at Huber familiar with the find and dig, and from Dr. Mike Voorhies.”

I spent a day in the field with Phil Manning & Ashley Quinn (Georgia College Natural History Museum) and we visited this site of Mine #34 (Latitude;32°43'49.94"N by Longitude;83°29'34.26"W), but it’s currently leased by a hunting club and hunted year-round. I appreciate Phil showing us around.

Phil reports that, way back when, the decision was made not to reclaim the Mine #34 but leave open and available for collection, education, and research purposes. Unfortunately, this was decades ago and the mining lease has long since expired. Perhaps at some point this small mine will again be available for education and research.

On the discovery of Ziggy, Billy Christy Jr. reports that he and his father had found a vein of calcite crystals in the upper Tivola Limestone and were following it when they encountered a mass of bones, about ten feet above the base of the Twiggs Clay.

Bill Christy called in Dr. Michael Voorhies, with the UGA at the time, to identify the fossil in the field and lead the effort to excavate and study the specimen at the University of Georgia. Dr. Voorhies identified the species as Zygorhiza kochii, which would have been readily accepted at the time but would later prove incorrect.

Dr. Voorhies is famous in his own right; after leaving UGA he stood as Professor of Vertebrate Paleontology at the University of Nebraska. He found national fame as the discoverer of Nebraska Ash Fall Beds which was developed into a state park and yielded many rich and important fossils finds. (http://ashfall.unl.edu/) He has since retired.

Bill Christy Sr. passed away in October 2010 but is fondly remembered by the Mid-Georgia Gem and Mineral Society. His son Billy Jr. currently lives in Midland, Texas and maintains membership in the society; he patiently answered many of my questions in a 10, March, 2014 phone interview.

Depending on 41 year old memories; Billy Jr. reported that about 6 inches of Ziggy’s lower snout and both mandibles were present in the sediments along with several ribs, vertebrae, teeth, and other bones.

The excavation began in the fall of 1973 and was complete by January 1974. The specimen jacketed for protection then transported to the University of Georgia for research. About 60% of a non-articulated individual was present. Non-articulated and missing remains suggest post-mortem scavenging of the whale.

Billy Christy Jr. was preparing for college at the time of the discovery and recovery of Ziggy and actively participated in both. He reported that while cleaning the Twiggs Clay from the fossils in the UGA lab he discovered two and a half small sand shark’s vertebrae stuck to the ribs, and some shark teeth. We don't know species of sand shark; there are several known to occur in the Twiggs Clay. This material has since been lost.

The presence of small shark vertebrae stuck to the Ziggy's ribs could certainly be interpreted as a final meal.

With the help of Rick Otto, Superintendent of Nebraska’s Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park I reached Dr. Voorhies for a phone interview on 18, March, 2014.

Dr. Voorhies stated that to his knowledge the specimen had never been seriously studied by science. The belief that it was a Zygorhiza kochii, based on A Review of Archaeocti by Remington Kellogg, did not warrant a research paper as the species was well known from Georgia’s fossil record.

Dr. Voorhies reported that Bill Christy Sr. had always intended for the specimen to end up on display at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon where Bill often volunteered and later worked. On March 3rd, 1979 the University of Georgia officially donated Ziggy to the Museum. In a 31, March, 2014 letter Susan Welsh, the Director of the Museum of Arts and Sciences reported that as a condition of the donation Ziggy was to be assembled into a mounted specimen.

From University of Georgia Ziggy travelled to the University of Florida as a disassembled puzzle with pieces missing. There; Robert Allen spent more than two years assembling the current mounting. This was an expensive, time consuming project.

A Zygorhiza kochii from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History was loaned and Ziggy’s missing elements were either cast or modelled from the Smithsonian specimen. This includes most of the skull. Allen mounted the actual Twiggs County fossils; the only artificial material in the current Ziggy display is the Smithsonian material.

This created a problem; Ziggy is actually a mixture of two genera of early whales. The pale original fossils are Dorudon serratus. The darker material is recreated from the Smithsonian Zygorhiza kochii specimen.

As we’ve seen Dr. Uhen travelled the southeast in 2012 and 2013 reviewing published fossils from various collections while he was working on his paper for the Alabama Museum of Natural History http://almnh.ua.edu/. He stopped in at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon. He didn’t see what he expected to see. As seen below his 2013 paper over basilosaurids classified Ziggy as a Dorudon serratus.

Dr. Voorhies agreed with the reclassification in light of Dr. Uhen’s expertise in basilosaurid whales.

The Identification of Ziggy

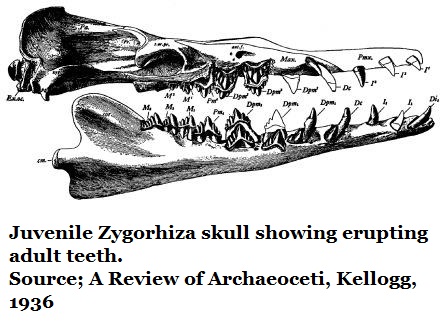

So how did Ziggy become misidentified?

In 1908, when Frederick True attempted to differentiate between the existing Dorudon and his newly coined Zygorhiza, he failed to recognize that specimen of Dorudon serratus he was using as a reference still possessed “baby” teeth.

Thus, many of the characteristics he used to differentiate the two genre were actually differences between deciduous juvenile teeth and adult teeth.

When Remington Kellogg compiled his 1936 A Review of the Archaeoceti the tooth mistake was perpetuated.

This, and other factors, caused widespread confusion and led to most small basilosaurids in North America being incorrectly identified as Zygorhiza kochii.

So how did Ziggy become misidentified?

In 1908, when Frederick True attempted to differentiate between the existing Dorudon and his newly coined Zygorhiza, he failed to recognize that specimen of Dorudon serratus he was using as a reference still possessed “baby” teeth.

Thus, many of the characteristics he used to differentiate the two genre were actually differences between deciduous juvenile teeth and adult teeth.

When Remington Kellogg compiled his 1936 A Review of the Archaeoceti the tooth mistake was perpetuated.

This, and other factors, caused widespread confusion and led to most small basilosaurids in North America being incorrectly identified as Zygorhiza kochii.

Ziggy Display

As of this writing (March/2015), if you visit the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon you will still see Ziggy identified as a Zygorhiza kochii; that will probably soon change.

The nearby text and online description both explain that the fossil was recovered from a Twiggs County kaolin mine, that the sediments containing the fossils were deposited on a beach, that these sediments are 40 million years old, and shark vertebrae found as stomach contents are evidence of the whale’s last meal.

As mentioned; two and a half small shark vertebrae were discovered by Billy Christy Jr., they were stuck to Ziggy's ribs. They might represent a last meal, we can do little more than speculate. This is not where Ziggy's stomach would have been but Ziggy's remains were not articulated nor were they complete, so the remains had been scavenged soon after death. It is possible that this relocated the remnants of the whale's last meal of shark. Its possible that Ziggy's last meal could have been fatal.

As of this writing (March/2015), if you visit the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon you will still see Ziggy identified as a Zygorhiza kochii; that will probably soon change.

The nearby text and online description both explain that the fossil was recovered from a Twiggs County kaolin mine, that the sediments containing the fossils were deposited on a beach, that these sediments are 40 million years old, and shark vertebrae found as stomach contents are evidence of the whale’s last meal.

As mentioned; two and a half small shark vertebrae were discovered by Billy Christy Jr., they were stuck to Ziggy's ribs. They might represent a last meal, we can do little more than speculate. This is not where Ziggy's stomach would have been but Ziggy's remains were not articulated nor were they complete, so the remains had been scavenged soon after death. It is possible that this relocated the remnants of the whale's last meal of shark. Its possible that Ziggy's last meal could have been fatal.

Dating the Find

With the state of knowledge in 1973 Voorhies correctly dated Ziggy at approximately 40 million years old. Over the intervening years the age of the Twiggs Clay has been continually refined.

In 1996 Dr. Ed Albin, an astronomer with Fernbank Science Center who researches Georgia’s tektites, used the potassium-argon process to date the Twiggs Clay and compare it with the known age of the Chesapeake Bay Impact Event. Albin’s research produced an age of 33.5 million years with an error rate + or – of 700,000 years.

With the state of knowledge in 1973 Voorhies correctly dated Ziggy at approximately 40 million years old. Over the intervening years the age of the Twiggs Clay has been continually refined.

In 1996 Dr. Ed Albin, an astronomer with Fernbank Science Center who researches Georgia’s tektites, used the potassium-argon process to date the Twiggs Clay and compare it with the known age of the Chesapeake Bay Impact Event. Albin’s research produced an age of 33.5 million years with an error rate + or – of 700,000 years.

More traditional dating methods, where the fossils are compared with the known age of other sediments is less accurate but more globally applicable. In this case, tiny, nearly microscopic fossils known as forams (short for foraminimfera) are used and the Twiggs falls into the P16 Foram zone. This dates the Twiggs Clay to between 33.5 to 34.5 million years old.

Correct dating is important; the Georgiacetus vogtlensis on display at Georgia Southern in Statesboro is Georgia’s oldest whale and was shown by Uhen in 2008 to lack a fluke.

Georgiacetus predates the basilosaurids; it is a protocetid or proto-whale. It is the most advanced known proto-whale. It is likely an ancestor to the basilosaurids. Georgiacetus has been confidently shown to be almost exactly 40 million years old.

Ziggy as a Durodon serratus is a basilosaurid. The basilosaurids emerged about 37 million years ago, reached worldwide distribution, and endured to 33.9 million years ago. Ziggy is significantly younger than Georgiacetus.

Ziggy cannot be 40 million years old. The sediments which held the fossils are only 33.5 million years old.

Correct dating is important; the Georgiacetus vogtlensis on display at Georgia Southern in Statesboro is Georgia’s oldest whale and was shown by Uhen in 2008 to lack a fluke.

Georgiacetus predates the basilosaurids; it is a protocetid or proto-whale. It is the most advanced known proto-whale. It is likely an ancestor to the basilosaurids. Georgiacetus has been confidently shown to be almost exactly 40 million years old.

Ziggy as a Durodon serratus is a basilosaurid. The basilosaurids emerged about 37 million years ago, reached worldwide distribution, and endured to 33.9 million years ago. Ziggy is significantly younger than Georgiacetus.

Ziggy cannot be 40 million years old. The sediments which held the fossils are only 33.5 million years old.

The Twiggs Clay Matrix

The matrix containing Ziggy is the Twiggs Clay; which is a very fine grained terrestrial clay deposited in a quiet, near shore, low energy, marine environment. In some locations the Twiggs Clay exceeds 100 feet in thickness.

Parts of it are rich in fossils; vertebrate, invertebrate and even plant fossils are recorded in the Twiggs Clay. It occurs in its greatest thickness near locations where our ancient rivers once emptied into the sea.

Sea levels were least 35 to 40 meters (115 feet to 131 feet) above modern levels when Ziggy lived. The coastline approximately followed the modern Fall Line.

The matrix containing Ziggy is the Twiggs Clay; which is a very fine grained terrestrial clay deposited in a quiet, near shore, low energy, marine environment. In some locations the Twiggs Clay exceeds 100 feet in thickness.

Parts of it are rich in fossils; vertebrate, invertebrate and even plant fossils are recorded in the Twiggs Clay. It occurs in its greatest thickness near locations where our ancient rivers once emptied into the sea.

Sea levels were least 35 to 40 meters (115 feet to 131 feet) above modern levels when Ziggy lived. The coastline approximately followed the modern Fall Line.

Death of Ziggy

Dr. Voorhies theorized that an adult whale had beached itself and died. Modern whales are voluntary breathers, not involuntary breathers like us.

Basilosaurids, including Ziggy, were fully marine adapted and likely possessed this trait as well.

Beaching is held as an act of desperation for a whale in trouble. We do not know Ziggy’s cause of death.

The whale was discovered near where the paleo-Oconee River had once emptied into the sea; perhaps the living whale had been in distress (from it's last meal?) and beached itself in the low tide surf.

Scavengers found the remains.

Nearly 34 million years later Huber’s mining operations leased the property and opened a new pit in Twiggs County. The miners cut their way through the Twiggs Clay, Tivola Limestone, and Clinchfield Formation to reach the Huber Formation and kaolin they sought.

With Huber’s permission two amateurs, a father and son, visited the site one day in search of fossils and mineral specimens… Fortunately, the Christys understood the importance of what they'd found. Today Ziggy is on public display for all to enjoy and learn from.

I look forward to seeing the completed revision of Ziggy’s display at the Museum of Arts & Sciences in Macon, GA. Until that time, remember; new fossils are only found in the field.

Dr. Voorhies theorized that an adult whale had beached itself and died. Modern whales are voluntary breathers, not involuntary breathers like us.

Basilosaurids, including Ziggy, were fully marine adapted and likely possessed this trait as well.

Beaching is held as an act of desperation for a whale in trouble. We do not know Ziggy’s cause of death.

The whale was discovered near where the paleo-Oconee River had once emptied into the sea; perhaps the living whale had been in distress (from it's last meal?) and beached itself in the low tide surf.

Scavengers found the remains.

Nearly 34 million years later Huber’s mining operations leased the property and opened a new pit in Twiggs County. The miners cut their way through the Twiggs Clay, Tivola Limestone, and Clinchfield Formation to reach the Huber Formation and kaolin they sought.

With Huber’s permission two amateurs, a father and son, visited the site one day in search of fossils and mineral specimens… Fortunately, the Christys understood the importance of what they'd found. Today Ziggy is on public display for all to enjoy and learn from.

I look forward to seeing the completed revision of Ziggy’s display at the Museum of Arts & Sciences in Macon, GA. Until that time, remember; new fossils are only found in the field.

References

Zygorhiza & Hydrarchos

A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013

Age of the Twiggs Clay

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

Georgiacetus lacked a fluke; led to modern whales through Dorudon;

New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

History of Ziggy

Personal communications; Billy Christy Jr, Phil Manning, Carl Joyce, Susan Welsh, Dr. Michael Voorhies, Dr. Mark Uhen.

Zygorhiza & Hydrarchos

A Review of North American Basilosauridae: Mark D. Uhen, 2013. Bulletin 31, Vol. 2, Alabama Museum of Natural History, April,1, 2013

Age of the Twiggs Clay

New Potassium-Argon Ages for Georgiaites and the Upper Eocene Dry Branch Formation (Twiggs Clay Member): Inferences about Tektite Stratigraphic Occurrence. E.F. Albin & J.M. Wampler, 1996

Georgiacetus lacked a fluke; led to modern whales through Dorudon;

New Protocetid Whales from Alabama and Mississippi, and a New Cetacean Clade, Pelagiceti. Mark D. Uhen. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No.3, September 2008, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

History of Ziggy

Personal communications; Billy Christy Jr, Phil Manning, Carl Joyce, Susan Welsh, Dr. Michael Voorhies, Dr. Mark Uhen.