|

|

|

9A: The Georgia Turtle

By Thomas Thurman

Agomphus oxysternum

Veatch & Stephenson;

Early Paleocene Epoch, roughly 61 million years old

From Montezuma, Georgia

To quote the 1911 text by Otto Veatch and Dr. Lloyd William Stephenson from Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; “A fossil turtle, Agomphus oxysternum, has been found in the Midway (Formation) near Montezuma. The specimen was first described by Cope (1877) and later by Hay (1908).”

This report represents a bit of a mystery as this species was unknown by several researchers I contacted. This suggests that the record of this roughly 61 million year old specimen was somewhat “lost” in the literature. It also leads into the history of the Georgia fossil and mineral collection, as well as the abolishment of the Georgia Geologic Survey.

The genus Agomphus is part of the Kinosternoidea superfamily of turtles which tend to be aquatic (fresh water) animals of varying mid to small size including musk and mud turtles. The total carapace (shell) of this individual was something more than a foot long in life.

Following the research of both Cope and Hay; in 1911 Veatch and Stephenson assigned this specimen to the Midway Formation of the Eocene Epoch; stating that Midway sediments directly overlay Cretaceous sediments near Montezuma. This was a mistake based in the understanding of these sediments in 1911; these formations were not accurately dated and properly understood until the late 1960s.

The term Midway (Group and/or Formation) is no longer used in Georgia; these sediments have been reassigned as the Clayton Formation.

After several decades of research and debate over its shell fossil content, including a period where it was viewed as a late Cretaceous formation, it has been re-assessed and placed confidently in the Paleocene Epoch. Specifically; it has been dated to the Danian Stage of the Early Paleocene Epoch, between 61.5 and 60 million years old.

Several Paleocene sediments overlay Cretaceous sediments in the Chattahoochee River Valley, reaching eastward to the Montezuma area and on into Houston County, Georgia. They stretch westward well into Alabama. The Clayton Formation is well known for invertebrate fossils, but vertebrate remains are very rare.

As the oldest Paleocene sediments in Georgia, they represent an unconformity; meaning that there is a gap in the sedimentary record. In this case, the extinction event separating the close of the Cretaceous, with its demise of the dinosaurs, and the opening of the Paleocene is not recorded.

John Hetrick’s 1990 Geologic Atlas of the Fort Valley Area includes northern Montezuma and shows Upper Cretaceous, Lower Paleocene and later deposits in the area around Montezuma. He confirms the unconformity between Paleocene’s Clayton Formation and underlying Cretaceous deposits. He also confirms the reassignment of the Midway Formation as the Clayton Formation. Hetrick notes that the Clayton Formation is “very obvious” in river bluffs just north of Montezuma and bears Paleocene guide fossils.

All of this serves to confirm that our turtle lived about 61 million years ago.

Veatch & Stephenson;

Early Paleocene Epoch, roughly 61 million years old

From Montezuma, Georgia

To quote the 1911 text by Otto Veatch and Dr. Lloyd William Stephenson from Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia; “A fossil turtle, Agomphus oxysternum, has been found in the Midway (Formation) near Montezuma. The specimen was first described by Cope (1877) and later by Hay (1908).”

This report represents a bit of a mystery as this species was unknown by several researchers I contacted. This suggests that the record of this roughly 61 million year old specimen was somewhat “lost” in the literature. It also leads into the history of the Georgia fossil and mineral collection, as well as the abolishment of the Georgia Geologic Survey.

The genus Agomphus is part of the Kinosternoidea superfamily of turtles which tend to be aquatic (fresh water) animals of varying mid to small size including musk and mud turtles. The total carapace (shell) of this individual was something more than a foot long in life.

Following the research of both Cope and Hay; in 1911 Veatch and Stephenson assigned this specimen to the Midway Formation of the Eocene Epoch; stating that Midway sediments directly overlay Cretaceous sediments near Montezuma. This was a mistake based in the understanding of these sediments in 1911; these formations were not accurately dated and properly understood until the late 1960s.

The term Midway (Group and/or Formation) is no longer used in Georgia; these sediments have been reassigned as the Clayton Formation.

After several decades of research and debate over its shell fossil content, including a period where it was viewed as a late Cretaceous formation, it has been re-assessed and placed confidently in the Paleocene Epoch. Specifically; it has been dated to the Danian Stage of the Early Paleocene Epoch, between 61.5 and 60 million years old.

Several Paleocene sediments overlay Cretaceous sediments in the Chattahoochee River Valley, reaching eastward to the Montezuma area and on into Houston County, Georgia. They stretch westward well into Alabama. The Clayton Formation is well known for invertebrate fossils, but vertebrate remains are very rare.

As the oldest Paleocene sediments in Georgia, they represent an unconformity; meaning that there is a gap in the sedimentary record. In this case, the extinction event separating the close of the Cretaceous, with its demise of the dinosaurs, and the opening of the Paleocene is not recorded.

John Hetrick’s 1990 Geologic Atlas of the Fort Valley Area includes northern Montezuma and shows Upper Cretaceous, Lower Paleocene and later deposits in the area around Montezuma. He confirms the unconformity between Paleocene’s Clayton Formation and underlying Cretaceous deposits. He also confirms the reassignment of the Midway Formation as the Clayton Formation. Hetrick notes that the Clayton Formation is “very obvious” in river bluffs just north of Montezuma and bears Paleocene guide fossils.

All of this serves to confirm that our turtle lived about 61 million years ago.

Romer’s 1966 edition of Vertebrate Paleontology assigned this turtle to North America’s Upper Cretaceous sediments. This was an inadvertent mistake on Romer’s part based on the understanding of the sediments at the time of his research.

The book Vertebrate Paleontology is an advanced textbook assembled by Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 to November 5, 1973) and originally published in 1933, revised in 1945 and again in 1966. Even at the time of the 1966 publication, most researchers would have probably accepted that the sediments which held our Agomphus oxysternum were of Late Cretaceous age, though that debate was still underway.

Edward Drinker Cope

(July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897)

Cope originally described this turtle, he was one of the two great early American paleontologists, the other being Othniel Charles Marsh. They were often bitter rivals see: The Bone Wars, for more this scientific feud.

Cope had little formal science education but published some 1400 research papers in his career with his first at 19 years old. Though asked at one point to teach, he declined, preferring field work.

He was a very active field paleontologist prospecting extensively in the American west. He described and named more than 1000 vertebrate species including hundreds of fish, dozens of dinosaurs and this turtle. Cope is one pillars of American paleontology his name is still very frequently encountered during paleontological research.

Cope’s findings over this Georgia turtle were read at the proceedings of the American Philosophical Society on July 20, 1877, below is the quoted passage from that meeting. Though he originally described the fossil, he assigned it to a different genus and proposed the name Amphiemys oxysternum, a name which would, in time, be overturned and re-assigned.

“Professor George Little, State Geologist of Georgia, placed in my hands for determination a Chelonite (turtle) from a Tertiary formation in Macon Co. of that State. The matrix is a rather soft limestone of a light drab color. When the specimen was first obtained it was nearly perfect, lacking only the posterior part of one side, and the posterior border of the carapace. Having been mutilated by destructive curiosity hunters, there remains now the plastron and the anterior half of the carapace, with a considerable portion of the posterior part of the left margin. The surface has been exposed to the weather so as to obscure, and in some places to obliterate the dermal sutures, while the skeletal sutures are distinct. The form has been slightly distorted by lateral pressure, but not much.”

Cope established this fossil as representing a species previously unknown to science.

In 1878, The American Naturalist, An Illustrated Magazine of Natural History, published the following text on page 129 as edited by A. S. Packard Jr. and Edward Cope. It is interesting to note what other fossils are listed in Georgia’s “valuable” collection; note also that the name Amphiemys oxysternum is still used, though this would change:

Paleontology Of Georgia.—Prof. Little, director of the Geological Survey of Georgia, has accumulated a valuable collection of the vertebrate fossils of that State, of cretaceous and tertiary age. Among these there have been identified the dinosaurian Hadrosaurus tripos, and the turtles Taphrosphys strenuus and Amphiemys oxysternum, a new genus and species related to Adocus. Mr. Loughridge of the survey also discovered a very fine specimen of Peritresius ornatus (sea turtle fossil).

As a note; Some of the fossils Cope commented on here have been since lost. In a personal communication from Dr. David Schwimmer (28/Dec/2014):

“Cope's ‘Hadrosaurus tripos’ was a mistaken identity of a whale vertebra, but that was based on a specimen from the Carolinas.”

“The specimen from the Chattahoochee River probably was a hadrosaur vertebra (since the surrounding rock is Cretaceous age), but he used the incorrect name in his attribution of it. Since the specimen disappeared, the matter is trivial.”

“By the way, I had a chance to see the original "tripos" in a visit to Princeton: obviously not dinosaur. I wonder what Cope was drinking (pun on his middle name)?”

Professor Oliver Perry Hay

(May 22, 1846 – November 2, 1930)

Hay was highly respected early American herpetologist, ichthyologist, zoologist and paleontologist. At various periods he worked for the Field Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Institution for Science and the United States National Museum (which is now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History).

He published extensively on fossil turtles and Pleistocene mammals; including historical work on Georgia’s ice age deposits. His work in creating catalogs over existing knowledge was well received and became standard reference sources for later researchers.

One such work is the Bibliography and Catalog of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America which Hay published in 1902 through the United States Geological Survey (Bulletin #179). Here we find a record of the reassignment for the Montezuma turtle from Cope’s Amphirmys oxysternum to the current Agomphus oxysternum.

Hay had a deep interest in turtles and in 1908 he published a major work on the contemporary state of the knowledge in this subject. This book was complete with expensive illustrations and photographs. It is entitled; The Fossil Turtles of North America and is available online as a free eBook download. This is the source for the line drawing appearing in this entry.

Hay visited Atlanta and inspected the Agomphus oxysternum fossil for his 1908 work; in those pages he recorded this passage:

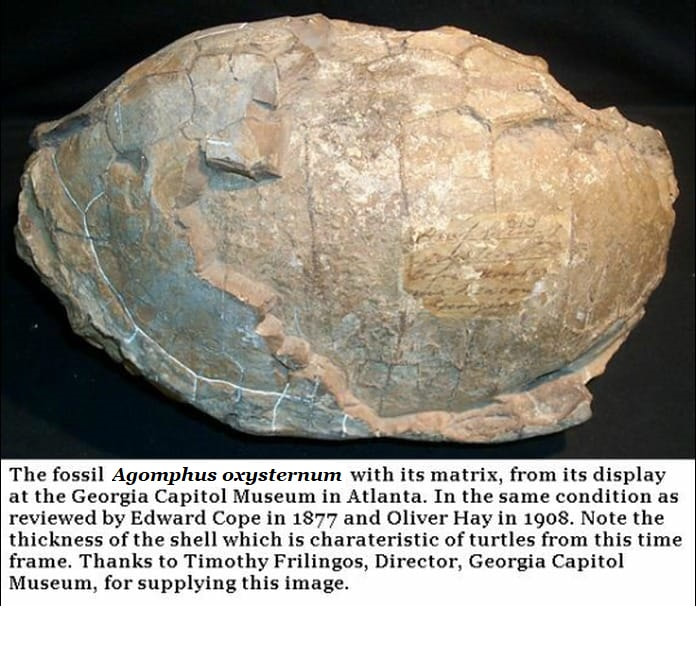

The holotype (holotype means fossil which established the species) of the species is in the collection of the Geological Survey of Georgia, at Atlanta, where the writer has been permitted to study it. The specimen was found near Monte-zuma, Macon County, near the Flint River, in what is known as the Midway formation, a member of the Lower Eocene (this was later revised). It is in the same condition as when it was described by Professor Cope, the plastron being present, as well as the anterior portion of the carapace and the left border as far as the hinder end of the eighth peripheral. The core of matrix which filled the shell is in large part present and on it are indicated the sutures between the series of neural and costal bones.

Today our Agomphus oxysternum is on display in a glass case on the fourth floor of the Georgia State Capitol Museum in the company of other Georgia fossils; though the museum staff could tell me little about its origin or history.

It is interesting to note the thickness of the turtle’s shell, which is typical of turtles from this time frame. Pressures from predation “selected” thicker shelled animals as a means of greater protection. Such thick shells are expensive for an animal to grow, requiring a large percentage of the animal’s nutritional intake. Today’s turtles have thinner shells, a thin shell ceased to be a liability in a world where predators tend to be smaller and their jaws tend to have less bite force.

This is the way natural selection responds to changing environments; while the thick shell represented an advantage, this expensive adaptation was reinforced. Once the advantage disappeared; the failure of the dinosaurs and large reptilian predators, the thick turtle shell became a liability, and thin shelled turtles found more reproduction opportunities.

References:

Georgia 1911; Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, Bulletin 26, Georgia Geologic Survey. Otto Veatch and Lloyd William Stephenson, Bulletin 26,Geological Survey of Georgia.1911

Geologic Atlas of the Fort Valley Area. Geologic Atlas 7, Georgia Geologic Survey. John H. Hetrick, 1990

Ebook: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. XVII, June 1877 to June 1878, Pages 82 to 84, By Edward D. Cope; Read aloud on 20/July/1877

Ebook; The American Naturalist, An Illustrated magazine, Natural History. Vol. XII, edited by A. S. Packard Jr. & Edward Cope, Page 129, Year1878 Passage on Georgia Paleontology.

Ebook; Bibliography and Catalog of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America; Bulletin 179 of the United States Geological Survey, 1902, by Oliver Perry Hay; Page 445

Ebook: The Fossil Turtles of North America; Published by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1908, by Oliver Perry Hay; Page 256

Clayton Formation, description:

Excursions in Southeastern Geology; Volume II, Edited by: Robert W. Frey and Thornton L. Neathery, Published in 1980 by: The American Geoscience Institute (AGI) (Formerly known as the American Geological Institute).

Field Trip Report: Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Geology of the Chattahoochee River Valley, Western Georgia and Eastern Alabama, By: Juergen Reinhardt, U.S. Geological Survey, National Center & Thomas G. Gibson, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. National Museum, With contributions by: Laurel M. Bybell, Lucy E. Edwards, and Norman O. Frederickson of the U.S. Geological Survey, National Center; Charles C. Smith & Norman F Sohl of the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. National Museum. Paleocene, Clayton Formation descriptions of stratigraphy and fossils by Thomas G. Gibson and Laurel M. Bybell

The book Vertebrate Paleontology is an advanced textbook assembled by Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 to November 5, 1973) and originally published in 1933, revised in 1945 and again in 1966. Even at the time of the 1966 publication, most researchers would have probably accepted that the sediments which held our Agomphus oxysternum were of Late Cretaceous age, though that debate was still underway.

Edward Drinker Cope

(July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897)

Cope originally described this turtle, he was one of the two great early American paleontologists, the other being Othniel Charles Marsh. They were often bitter rivals see: The Bone Wars, for more this scientific feud.

Cope had little formal science education but published some 1400 research papers in his career with his first at 19 years old. Though asked at one point to teach, he declined, preferring field work.

He was a very active field paleontologist prospecting extensively in the American west. He described and named more than 1000 vertebrate species including hundreds of fish, dozens of dinosaurs and this turtle. Cope is one pillars of American paleontology his name is still very frequently encountered during paleontological research.

Cope’s findings over this Georgia turtle were read at the proceedings of the American Philosophical Society on July 20, 1877, below is the quoted passage from that meeting. Though he originally described the fossil, he assigned it to a different genus and proposed the name Amphiemys oxysternum, a name which would, in time, be overturned and re-assigned.

“Professor George Little, State Geologist of Georgia, placed in my hands for determination a Chelonite (turtle) from a Tertiary formation in Macon Co. of that State. The matrix is a rather soft limestone of a light drab color. When the specimen was first obtained it was nearly perfect, lacking only the posterior part of one side, and the posterior border of the carapace. Having been mutilated by destructive curiosity hunters, there remains now the plastron and the anterior half of the carapace, with a considerable portion of the posterior part of the left margin. The surface has been exposed to the weather so as to obscure, and in some places to obliterate the dermal sutures, while the skeletal sutures are distinct. The form has been slightly distorted by lateral pressure, but not much.”

Cope established this fossil as representing a species previously unknown to science.

In 1878, The American Naturalist, An Illustrated Magazine of Natural History, published the following text on page 129 as edited by A. S. Packard Jr. and Edward Cope. It is interesting to note what other fossils are listed in Georgia’s “valuable” collection; note also that the name Amphiemys oxysternum is still used, though this would change:

Paleontology Of Georgia.—Prof. Little, director of the Geological Survey of Georgia, has accumulated a valuable collection of the vertebrate fossils of that State, of cretaceous and tertiary age. Among these there have been identified the dinosaurian Hadrosaurus tripos, and the turtles Taphrosphys strenuus and Amphiemys oxysternum, a new genus and species related to Adocus. Mr. Loughridge of the survey also discovered a very fine specimen of Peritresius ornatus (sea turtle fossil).

As a note; Some of the fossils Cope commented on here have been since lost. In a personal communication from Dr. David Schwimmer (28/Dec/2014):

“Cope's ‘Hadrosaurus tripos’ was a mistaken identity of a whale vertebra, but that was based on a specimen from the Carolinas.”

“The specimen from the Chattahoochee River probably was a hadrosaur vertebra (since the surrounding rock is Cretaceous age), but he used the incorrect name in his attribution of it. Since the specimen disappeared, the matter is trivial.”

“By the way, I had a chance to see the original "tripos" in a visit to Princeton: obviously not dinosaur. I wonder what Cope was drinking (pun on his middle name)?”

Professor Oliver Perry Hay

(May 22, 1846 – November 2, 1930)

Hay was highly respected early American herpetologist, ichthyologist, zoologist and paleontologist. At various periods he worked for the Field Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Institution for Science and the United States National Museum (which is now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History).

He published extensively on fossil turtles and Pleistocene mammals; including historical work on Georgia’s ice age deposits. His work in creating catalogs over existing knowledge was well received and became standard reference sources for later researchers.

One such work is the Bibliography and Catalog of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America which Hay published in 1902 through the United States Geological Survey (Bulletin #179). Here we find a record of the reassignment for the Montezuma turtle from Cope’s Amphirmys oxysternum to the current Agomphus oxysternum.

Hay had a deep interest in turtles and in 1908 he published a major work on the contemporary state of the knowledge in this subject. This book was complete with expensive illustrations and photographs. It is entitled; The Fossil Turtles of North America and is available online as a free eBook download. This is the source for the line drawing appearing in this entry.

Hay visited Atlanta and inspected the Agomphus oxysternum fossil for his 1908 work; in those pages he recorded this passage:

The holotype (holotype means fossil which established the species) of the species is in the collection of the Geological Survey of Georgia, at Atlanta, where the writer has been permitted to study it. The specimen was found near Monte-zuma, Macon County, near the Flint River, in what is known as the Midway formation, a member of the Lower Eocene (this was later revised). It is in the same condition as when it was described by Professor Cope, the plastron being present, as well as the anterior portion of the carapace and the left border as far as the hinder end of the eighth peripheral. The core of matrix which filled the shell is in large part present and on it are indicated the sutures between the series of neural and costal bones.

Today our Agomphus oxysternum is on display in a glass case on the fourth floor of the Georgia State Capitol Museum in the company of other Georgia fossils; though the museum staff could tell me little about its origin or history.

It is interesting to note the thickness of the turtle’s shell, which is typical of turtles from this time frame. Pressures from predation “selected” thicker shelled animals as a means of greater protection. Such thick shells are expensive for an animal to grow, requiring a large percentage of the animal’s nutritional intake. Today’s turtles have thinner shells, a thin shell ceased to be a liability in a world where predators tend to be smaller and their jaws tend to have less bite force.

This is the way natural selection responds to changing environments; while the thick shell represented an advantage, this expensive adaptation was reinforced. Once the advantage disappeared; the failure of the dinosaurs and large reptilian predators, the thick turtle shell became a liability, and thin shelled turtles found more reproduction opportunities.

References:

Georgia 1911; Geology of the Coastal Plain of Georgia, Bulletin 26, Georgia Geologic Survey. Otto Veatch and Lloyd William Stephenson, Bulletin 26,Geological Survey of Georgia.1911

Geologic Atlas of the Fort Valley Area. Geologic Atlas 7, Georgia Geologic Survey. John H. Hetrick, 1990

Ebook: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. XVII, June 1877 to June 1878, Pages 82 to 84, By Edward D. Cope; Read aloud on 20/July/1877

Ebook; The American Naturalist, An Illustrated magazine, Natural History. Vol. XII, edited by A. S. Packard Jr. & Edward Cope, Page 129, Year1878 Passage on Georgia Paleontology.

Ebook; Bibliography and Catalog of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America; Bulletin 179 of the United States Geological Survey, 1902, by Oliver Perry Hay; Page 445

Ebook: The Fossil Turtles of North America; Published by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1908, by Oliver Perry Hay; Page 256

Clayton Formation, description:

Excursions in Southeastern Geology; Volume II, Edited by: Robert W. Frey and Thornton L. Neathery, Published in 1980 by: The American Geoscience Institute (AGI) (Formerly known as the American Geological Institute).

Field Trip Report: Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Geology of the Chattahoochee River Valley, Western Georgia and Eastern Alabama, By: Juergen Reinhardt, U.S. Geological Survey, National Center & Thomas G. Gibson, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. National Museum, With contributions by: Laurel M. Bybell, Lucy E. Edwards, and Norman O. Frederickson of the U.S. Geological Survey, National Center; Charles C. Smith & Norman F Sohl of the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. National Museum. Paleocene, Clayton Formation descriptions of stratigraphy and fossils by Thomas G. Gibson and Laurel M. Bybell