14Q; Bibb County's Christy Hill

Clinchfield Formation Hilltop

By;

Thomas Thurman

22/Oct/2022

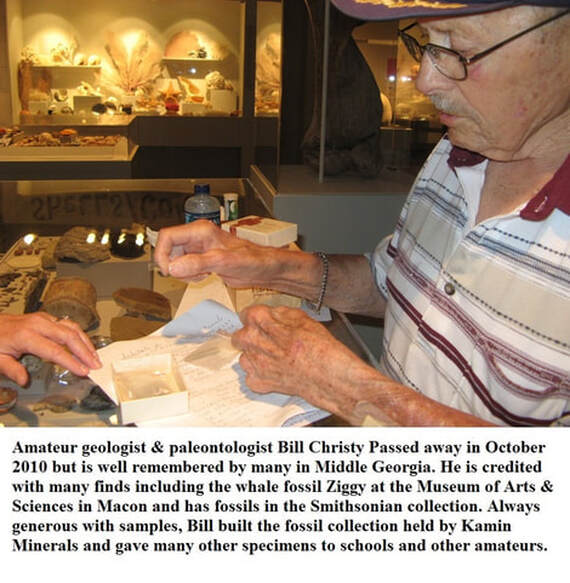

Bill Christy

Exposures of the Clinchfield Formation are rare, but it’s often rich in fossils.

I spent a day in the field with Bill Christy, back in 1995. Back then Mr. Bill was a respected local amateur who knew his way around. I was a rank beginner who knew nothing.

Exposures of the Clinchfield Formation are rare, but it’s often rich in fossils.

I spent a day in the field with Bill Christy, back in 1995. Back then Mr. Bill was a respected local amateur who knew his way around. I was a rank beginner who knew nothing.

After driving through a maze of east Macon back roads Bill Christy led me to a hill near the junction of Bibb, Twiggs, and Jones Counties. It’d rained earlier and the steepish dirt road climbing the hill looked sketchy, but ever-bold Thomas made the attempt in my car. About halfway up I lost traction and we slid backwards and sideways back down the hill with neither the accelerator nor brake pedal having any affect. It sounds terrifying but it all happened in such slow motion that both of us started laughing nervously. Fortunately, we didn’t hit anything or get stuck. I parked the car, and we walked up the hill.

I was completely unaware of Mr. Bill’s reputation. He was well seasoned with historic finds under his belt and specimens he’d recovered in several university collections, museums, and even the Smithsonian. Hell, he’d discovered Ziggy, the Durodon serratus on display at the Macon Museum of Arts & Sciences and brought in his friend Dr. Michael Voorhies to help recover and prep the find. (See Section 13 of this website.) Sadly, Bill Christy passed in October of 2010.

I was completely unaware of Mr. Bill’s reputation. He was well seasoned with historic finds under his belt and specimens he’d recovered in several university collections, museums, and even the Smithsonian. Hell, he’d discovered Ziggy, the Durodon serratus on display at the Macon Museum of Arts & Sciences and brought in his friend Dr. Michael Voorhies to help recover and prep the find. (See Section 13 of this website.) Sadly, Bill Christy passed in October of 2010.

Atop that hill Mr. Bill showed me marine fossils, seashells, in boulders often stacked on the hilltop. There was enough visible rock on the ground to know the boulders occurred naturally, no doubt heavy equipment had been used to relocate loose boulders during road construction.

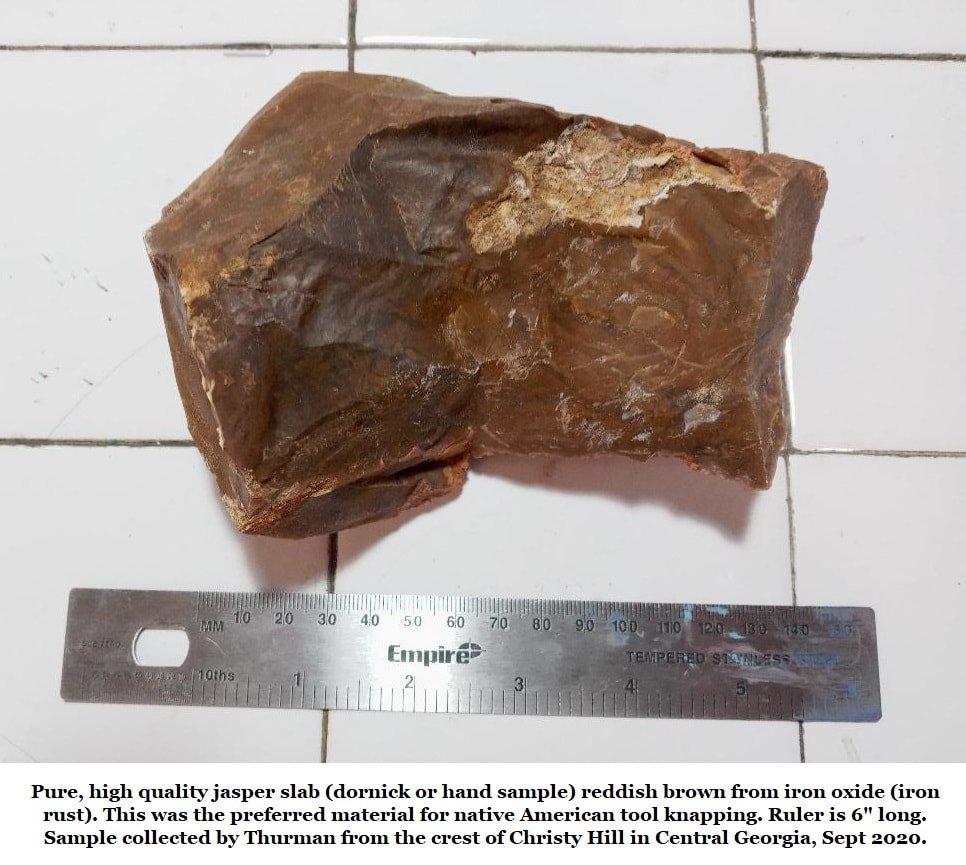

The hilltop marine fossils are cool. I was equally fascinated by the dense smooth veins of hard jasper which ranges from translucent to reddish brown, which could be followed like a trial in the rock of the hilltop. At the time I didn’t really understand any of it. I collected some samples and picked up a few fossils for my collection.

I never forgot the site in the years that followed, in my mind it became Christy Hill, but I didn’t remember exactly where it was. I went looking for it a few times, but it was 25 years later, in 2020, when I found it again. By then I understood what I was looking at.

The hilltop marine fossils are cool. I was equally fascinated by the dense smooth veins of hard jasper which ranges from translucent to reddish brown, which could be followed like a trial in the rock of the hilltop. At the time I didn’t really understand any of it. I collected some samples and picked up a few fossils for my collection.

I never forgot the site in the years that followed, in my mind it became Christy Hill, but I didn’t remember exactly where it was. I went looking for it a few times, but it was 25 years later, in 2020, when I found it again. By then I understood what I was looking at.

Christy Hill

The hillcrest stands a few air miles east of downtown Macon, 525 feet above sea level, and is crowned with fossil rich, brick-red stained, chert boulders of Georgia’s 35.4-million-year-old Clinchfield Formation. The coloration comes from oxidized iron.

Why is it odd for this central Georgia hilltop to be crowned with marine fossils? The elevation of Downtown Macon is about 450 feet, so when these sediments were laid down sea levels were high enough to submerge downtown. Browns Mount, along the Ocmulgee River in south Macon stands at about 550 feet so perhaps it, and a few other hilltops, stood as a barrier islands. The Ocmulgee River certainly existed, but it met the sea on a coastline north of Macon.

The hillcrest stands a few air miles east of downtown Macon, 525 feet above sea level, and is crowned with fossil rich, brick-red stained, chert boulders of Georgia’s 35.4-million-year-old Clinchfield Formation. The coloration comes from oxidized iron.

Why is it odd for this central Georgia hilltop to be crowned with marine fossils? The elevation of Downtown Macon is about 450 feet, so when these sediments were laid down sea levels were high enough to submerge downtown. Browns Mount, along the Ocmulgee River in south Macon stands at about 550 feet so perhaps it, and a few other hilltops, stood as a barrier islands. The Ocmulgee River certainly existed, but it met the sea on a coastline north of Macon.

The Clinchfield Formation

The Clinchfield Formation used to be called the Clinchfield Sand and was named for a highly fossiliferous, fairly loose sand sporadically occurring beneath the Tivola Limestone in the quarries of Houston County. Clinchfield is the very small town in Houston County where the quarry office stands.

The Clinchfield Formation is Georgia’s most productive source for vertebrate fossils. It is often rich in teeth, shells, and there was even a reef-like bed of giant oysters (Crassostrea gigantissima) reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering in one of the quarry pits of Houston County. (This reef has long since been mined out.) The Clinchfield, as a loose sand, only occurs on the surface very rarely and is easily washed away.

The Clinchfield Formation used to be called the Clinchfield Sand and was named for a highly fossiliferous, fairly loose sand sporadically occurring beneath the Tivola Limestone in the quarries of Houston County. Clinchfield is the very small town in Houston County where the quarry office stands.

The Clinchfield Formation is Georgia’s most productive source for vertebrate fossils. It is often rich in teeth, shells, and there was even a reef-like bed of giant oysters (Crassostrea gigantissima) reported in 1970 by Sam Pickering in one of the quarry pits of Houston County. (This reef has long since been mined out.) The Clinchfield, as a loose sand, only occurs on the surface very rarely and is easily washed away.

There is a notable exception to this at Rich Hill in Crawford County, 27 miles west-southwest of Christy Hill. Rich Hill stands more than 700 feet above sea level and is capped by orange, sandy, clay-rich soil. Beneath that is the Twiggs Clay, Tivola Limestone and finally the Clinchfield Formation. Rich Hill is in a rugged hilly area, on private property, and difficult to access. (See Section 14P of this website for details on Rich Hill)

In Houston County the Clinchfield Formation occurs at roughly 270 feet in elevation and is overlain by 30+ feet of Tivola Limestone and up to 100ft of Twiggs Clay. The local quarry mining the local Tivola Limestone reports that there are beds of Clinchfield limestone in the formation starting about 6 to 10 feet down. Samples of this material have not been made available.

As we’ve seen, the Clinchfield doesn’t always occur as a loose sand, thus Huddlestun and Hetrick reassigned the Clinchfield Sand as the Clinchfield Formation.

In Houston County the Clinchfield Formation occurs at roughly 270 feet in elevation and is overlain by 30+ feet of Tivola Limestone and up to 100ft of Twiggs Clay. The local quarry mining the local Tivola Limestone reports that there are beds of Clinchfield limestone in the formation starting about 6 to 10 feet down. Samples of this material have not been made available.

As we’ve seen, the Clinchfield doesn’t always occur as a loose sand, thus Huddlestun and Hetrick reassigned the Clinchfield Sand as the Clinchfield Formation.

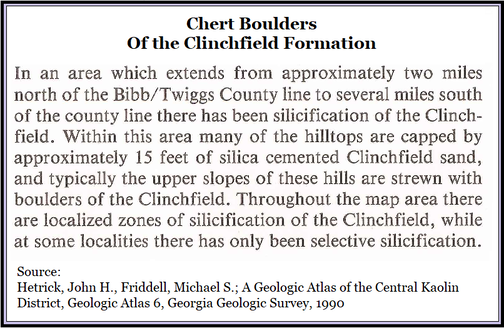

There are multiple hilltops reported in the geologic atlases that are capped by silicified Clinchfield Formation. Christy Hill is one such hilltop. Silicified means the sand was turned to rock when it was inundated with silica rich ground water. To date, no vertebrate fossils have been seen on Christy Hill.

The Houston County presence of Crassostrea gigantissima is telling, the genus usually lives in the inter-tidal zone (also known as the littoral zone) right on the coastline, so that they’re submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide. They do well in waters with a low nutrient supply.

The Houston County presence of Crassostrea gigantissima is telling, the genus usually lives in the inter-tidal zone (also known as the littoral zone) right on the coastline, so that they’re submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide. They do well in waters with a low nutrient supply.

Dating the Clinchfield

The age of the Clinchfield was set at roughly 35.4 million years by S. M. Herrick in 1972 using the contents of oyster samples Pickering collected from the Houston County oyster reef in 1970. (See section 14B of this website.)

Before the reef was mined out, Sam Pickering collected complete giant oyster fossils and sent them to John Herrick at the USGS. Herrick opened the oysters and found a wealth of microscopic foraminifera fossils inside. He identified the various species and dated the Clinchfield Formation using research on the emergence and extinction times of foraminifera species.

The same oyster species, Crassotrea gigantissima, also occurs frequently in the boulders at Christy Hill, 30 miles north-northeast from the Clinchfield oyster beds reported by Pickering & Herrick. The hillltop occurrence isn’t a reef-like accumulation but enough individuals are present that a reef likely existed nearby. This hilltop was likely exposed at low tide when these oysters lived. Maybe the oysters were dislodged in a tsunami.

The age of the Clinchfield was set at roughly 35.4 million years by S. M. Herrick in 1972 using the contents of oyster samples Pickering collected from the Houston County oyster reef in 1970. (See section 14B of this website.)

Before the reef was mined out, Sam Pickering collected complete giant oyster fossils and sent them to John Herrick at the USGS. Herrick opened the oysters and found a wealth of microscopic foraminifera fossils inside. He identified the various species and dated the Clinchfield Formation using research on the emergence and extinction times of foraminifera species.

The same oyster species, Crassotrea gigantissima, also occurs frequently in the boulders at Christy Hill, 30 miles north-northeast from the Clinchfield oyster beds reported by Pickering & Herrick. The hillltop occurrence isn’t a reef-like accumulation but enough individuals are present that a reef likely existed nearby. This hilltop was likely exposed at low tide when these oysters lived. Maybe the oysters were dislodged in a tsunami.

So How Do We Know This is the Clinchfield Formation?

We can identify the formation three different ways. First of all stratigraphy. In Houston County the Twiggs Clay often occurs on or near the hilltops, beneath this is the Tivola Limestone, and beneath the Tivola is the Clinchfield Formation. Further north, in Bibb, Twiggs, and Wilkinson Counties any of these three formations may be absent, weathered away. At Christy Hill, both the Tivola Limestone and the Twiggs Clay are absent.

Secondly, in the north bank of a road cut on Georgia Highway 57, just west of the Twiggs County/Wilkinson County line there is a steep hill topped by 30 feet of Twiggs Clay with the Clinchfield Formation occurring immediately below at an approximately elevation of 490 feet. The Tivola Limestone is absent here. This location is 2 miles north of Christy Hill. Here the Clinchfield Formation is white, silicified but not iron stained, its actually rather loose, easily worked. There are no veins of jasper. It is dense with small shells and gastropods are also moderately common. No vertebrate remains were observed. Besides coloration, the Hwy 57 exposure is identical to Christy Hill.

Lastly; Hetrick and Friddell reported multiple hills crowned by silicified chert boulders of the Clinchfield Formation in their 1990 atlas of the area.

We can identify the formation three different ways. First of all stratigraphy. In Houston County the Twiggs Clay often occurs on or near the hilltops, beneath this is the Tivola Limestone, and beneath the Tivola is the Clinchfield Formation. Further north, in Bibb, Twiggs, and Wilkinson Counties any of these three formations may be absent, weathered away. At Christy Hill, both the Tivola Limestone and the Twiggs Clay are absent.

Secondly, in the north bank of a road cut on Georgia Highway 57, just west of the Twiggs County/Wilkinson County line there is a steep hill topped by 30 feet of Twiggs Clay with the Clinchfield Formation occurring immediately below at an approximately elevation of 490 feet. The Tivola Limestone is absent here. This location is 2 miles north of Christy Hill. Here the Clinchfield Formation is white, silicified but not iron stained, its actually rather loose, easily worked. There are no veins of jasper. It is dense with small shells and gastropods are also moderately common. No vertebrate remains were observed. Besides coloration, the Hwy 57 exposure is identical to Christy Hill.

Lastly; Hetrick and Friddell reported multiple hills crowned by silicified chert boulders of the Clinchfield Formation in their 1990 atlas of the area.

Chert

What does the term silicified boulders mean? It means that silica has cemented and hardened the sand into rock, into chert, it has even filled many of the gaps in the rock and created the veins of jasper. (Jasper is a form of chert.) So where did the silica come from?

These boulders started off, 34.5 million years ago, as fossiliferous sand beds, rich in shells. Some of it was likely limestone too. Over the many millennia this hilltop was buried by later sediments. Very likely the Twiggs Clay was deposited over these sediments soon after the Clinchfield was laid down. The Twiggs Clay is impermeable to water. While the hilltop was buried it became charged with silica rich groundwater, it was an aquifer.

As mentioned before, north of Christy Hill on Highway 57, there is another silica cemented Clinchfield Formation bed which is still covered by 30ft of Twiggs Clay.

What does the term silicified boulders mean? It means that silica has cemented and hardened the sand into rock, into chert, it has even filled many of the gaps in the rock and created the veins of jasper. (Jasper is a form of chert.) So where did the silica come from?

These boulders started off, 34.5 million years ago, as fossiliferous sand beds, rich in shells. Some of it was likely limestone too. Over the many millennia this hilltop was buried by later sediments. Very likely the Twiggs Clay was deposited over these sediments soon after the Clinchfield was laid down. The Twiggs Clay is impermeable to water. While the hilltop was buried it became charged with silica rich groundwater, it was an aquifer.

As mentioned before, north of Christy Hill on Highway 57, there is another silica cemented Clinchfield Formation bed which is still covered by 30ft of Twiggs Clay.

On Christy Hill the Clinchfield is various shades of brick red in color. On Highway 57 the Clinchfield is white. The difference is the presence of oxidized iron. Clearly the old aquifer at Christ Hilly contains significant iron oxide (rusted iron), along with silica. The old aquifer at Highway 57 lacked iron, it may have been filtered out by the sand.

On Christy Hill the iron oxide staining is highly variable. Some of the jasper is very nearly white or translucent. However, it’s the silica, not the iron, which turned sand to rock.

You may be familiar with the way acidic groundwater can dissolve limestone and other rock, silica rich ground water does just the opposite, it hardens rock. In fact, it can dramatically harden rock. Some of the rock on Christy Hill is hard enough to make a heavy rock hammer ring when it strikes the rock.

As the millennia passed, the overlying deposits were weathered away from these hilltops, but the hardened, silicified Clinchfield Formation is now highly resistant to erosion. The material exposed in the veins is pure, flawless reddish-brown jasper. Weathering does not touch hard chert. Except for the activities & tools of man, these hard, fossil rich boulders have lasted millennia and could easily last many more millennia.

On Christy Hill the iron oxide staining is highly variable. Some of the jasper is very nearly white or translucent. However, it’s the silica, not the iron, which turned sand to rock.

You may be familiar with the way acidic groundwater can dissolve limestone and other rock, silica rich ground water does just the opposite, it hardens rock. In fact, it can dramatically harden rock. Some of the rock on Christy Hill is hard enough to make a heavy rock hammer ring when it strikes the rock.

As the millennia passed, the overlying deposits were weathered away from these hilltops, but the hardened, silicified Clinchfield Formation is now highly resistant to erosion. The material exposed in the veins is pure, flawless reddish-brown jasper. Weathering does not touch hard chert. Except for the activities & tools of man, these hard, fossil rich boulders have lasted millennia and could easily last many more millennia.

Georgiaites

For those of you interested in tektites (georgiaites), it is possible that georgiaites could exist, in situ, in these boulders. Georgia’s tektites and the Clinchfield Formation have been shown to be approximately the same age. (For more on georgiaites in the Clinchfield see Page 14B of this website.) It’s entirely possible that georgiaites fell into the waters which created this fossil bed and were preserved within the sand, and eventually rock. I know of no reason why the glassy georgiaites would have been damaged or destroyed.

For those of you interested in tektites (georgiaites), it is possible that georgiaites could exist, in situ, in these boulders. Georgia’s tektites and the Clinchfield Formation have been shown to be approximately the same age. (For more on georgiaites in the Clinchfield see Page 14B of this website.) It’s entirely possible that georgiaites fell into the waters which created this fossil bed and were preserved within the sand, and eventually rock. I know of no reason why the glassy georgiaites would have been damaged or destroyed.

Still, I Have Questions…

- There are some questions posed by these hilltop exposures of the Clinchfield Formation, there is a significant variation in elevation. Bear in mind this is the same Clinchfield Formation. Could this represent an uplift event on the northern Coastal Plain?

- Christy Hill stands at 525 feet in elevation

- The Highway 57 exposure stands at 490 feet

- The Rich Hill exposure is about 530 feet.

- In the Houston County quarries it occurs at roughly 270 feet

- Coloration

- The white Clinchfield along Highway 57 is typical on the northern Coastal plain and is also seen in Wilkinson County.

- Is the iron oxide staining at Christy Hill an isolated, random event?

- Erosion?

- Clinchfield Formation, Twiggs Clay, and Tivola Limestone are all sporadic in occurrence.

- This is usually attributed to erosion.

- But on Highway 57 we see direct contact between the Twiggs Clay and Clinchfield Formation. There is no sign of the Tivola Limestone.

- These two are very close in age, so was the Tivola deposited and eroded in a very short time? A few hundred thousand years?

- Clinchfield Formation, Twiggs Clay, and Tivola Limestone are all sporadic in occurrence.

- The Tivola Limestone

- Tivola Limestone occurs, sporadically along the northern Coastal Plain.

- It is known from Rich Hill (Crawford County), Houston County (where it’s 30 feet thick), and Wilkinson County.

- This suggest that it was once widespread and continuous.

- The random nature is usually attributed to erosion.

- Which creates the question why the erosion was so unpredictable.

References

- Pickering, Sam M.; Stratigraphy, Paleontology, and Economic Geology of Portions of Perry and Cochran Quadrangles. The Geological Survey of Georgia, Department of Mines, Mining and Geology, Bulletin 81. 1970.

- Huddlestun, Paul F., & Hetrick, John H. Upper Eocene Stratigraphy of Central and Eastern Georgia, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Environmental Protection Division, Bulletin 95. 1986

- Hetrick, John H., Friddell, Michael S.; A Geologic Atlas of the Central Georgia Kaolin District; Geologic Atlas 6, Georgia Geologic Survey, 1990

- Herrick, S. M.; Age and Correlation of the Clinchfield Sand in Georgia. Contributions to Stratigraphy, Geological Survey Bulletin 1354-E, USGS 1972